Problems are comparatively easy to deal with.” This statement welcomes the reader of John Kørner’s 2004 artist book A Modern Problem. But don’t the unresolved problems of these modern times really scare us to death? Who doesn’t prefer a world without problems and in fact goes out of their way to avoid a problem?

The artist takes over the role of the presenter of ‘self-inflicted’ problems, reflecting society as “a series of fragmented situations, with every little element, physical or non-physical, seen as an isolated problem.” This is the chance to take nothing for granted — and take on the initiative, since “a considerable amount of creativity and energy are produced by the process of solving these problems… so the creation of problems… should be like petrol for new challenges.”

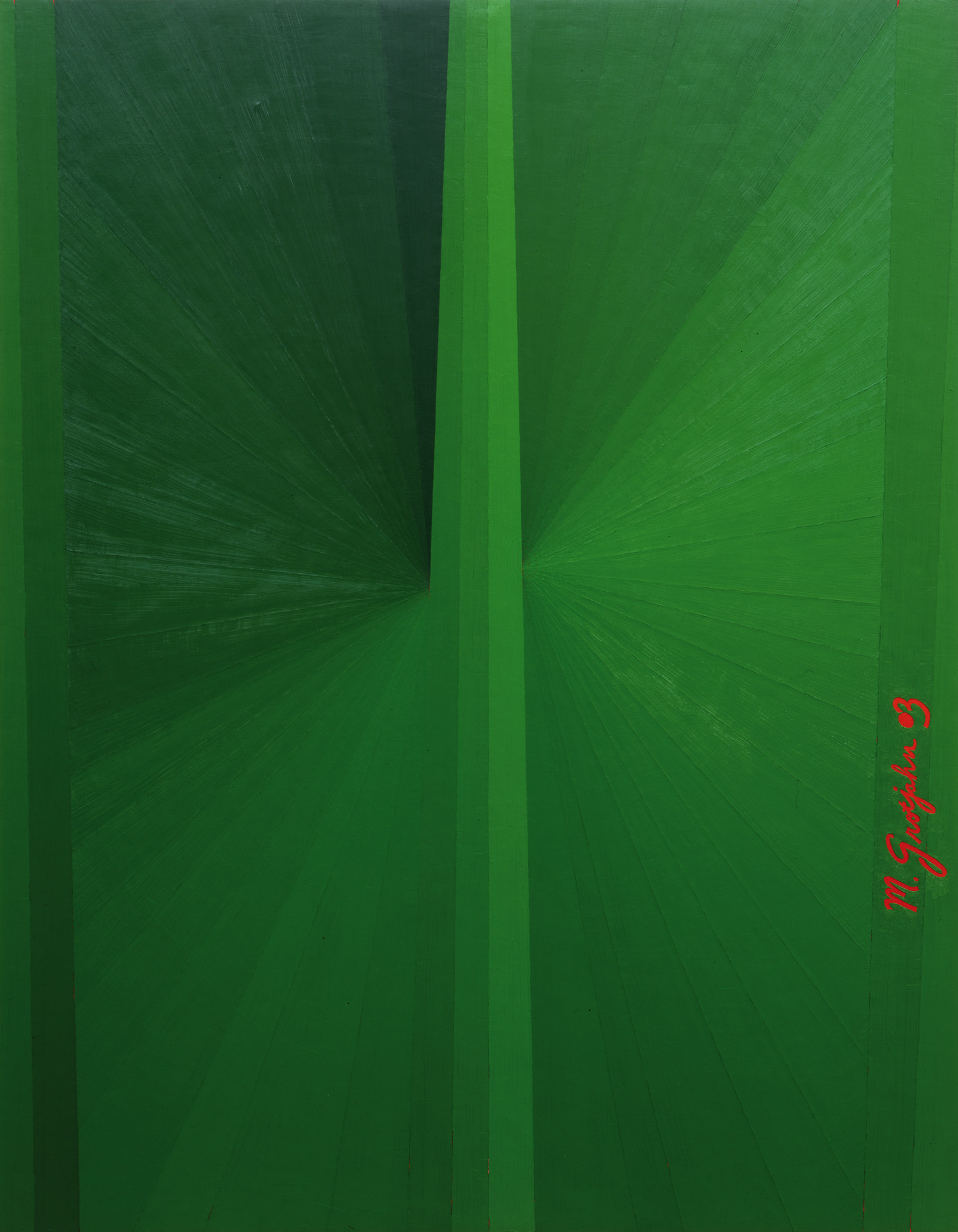

Reuniting the concept of direct, informally articulated imagery with the return of the painter-philosopher, Kørner’s work turns the abstract plane of the canvas into a colored minefield of possibilities, reflecting reality more than attempting to represent it. Every color, every figure and every paint stroke, every dot and mark has a name, a particular relevance akin to a word, a sentence or a semicolon in a text. Yet with the difference that it allows for more complex means of representation and interpretation, while maintaining a simplicity: painting is a problem.

This makes it tricky to describe the work of Kørner. His canvases, with their watered-down acrylics, are straightforward, figurative and recognizable for their intense, clear colors that at first glance exude emotions between child-like happiness, happy-go-lucky playfulness, zany optimism bordering on the esoteric, if not outright neurotic. His handling of paint is confident, gutsy, yet varied, controlled, with no fear of simplicity or complex situations. And a whole box of tricks and schemes, that on closer inspection gives the artist the access to a whole new concept of painting and to examine its genuine possibilities against a clearly contemporary background — with a multitude of historical, formalist and painterly references. An emerging scenery of period costumes, buildings and paraphernalia of the turn of the century — the formative time of modern industrialized society — is agitated by abstract forms, thereby producing complexities of philosophical proportions.

One of his recent works, Alone with Problems (2006), shows a sketchy, dark figure crouching in front of a pot as if in the process of planting a bizarre tree. The figure could be a farmer, but it consists of little more than boots, purple trousers and a greenish shirt, with a black extension — an arm, a burnt twig, or something even more sinister — emerging from it. It has more of a scarecrow look, faceless and limbless as it is, hovering on the bright yellow plane that occupies the lower half of the painting. A purple rural farmhouse in the background adds to the surreal feel of the scenery; detached from both worlds, its simple, regular structure hints at an undercurrent of decorative patterns. The figure is headless, as if decapitated by the horizon, and where one would expect the head, there is a hurricane of orange waves, light blues, purples and reds, distorting the gardener’s strange plants to a mere splotch of discolored paint. The hurricane’s eye is a white sphere, lined by a chain of unlikely red dots — abstract problem indicators. There is hardly any real weight, nor is there a decisive expressionist stance to all of this. Even if this hardly suggests the earthen heaviness of a farmer on a field, the loftiness of a scarecrow is rendered with the light-hearted panache of a scribbled mathematical hypothesis on a university blackboard.

Kørner questions the very concept of painting from level zero: drawing, the concept and the symbolism of black-and-white. Black and white are absolute terms, both represent no color (or all colors), but light and darkness, good and evil, or emptiness and fullness. In Western culture black is the authoritative color of absolute certainty, death. It is also the color of the written word in books and newspapers. So it is obvious that once something is written down, it is affirmed, certain, pinned down and consequently dead.

With the simple twist of supplementing the endless shades of the color wheel for the black-and-white contrast, Kørner has achieved a remarkable feat by substituting yellow for white, making it play the role of the void, the virginal, unmarked field of the ‘unpainted canvas.’ Suddenly this sunny yellow is light years removed from the joyous impression of a sun-drenched room, or the innocence of egg yolk, and assumes a quasi-institutional importance of, say, a post office. Consequently the role of black, due to complementary contrast, rests with purple, the color of papal robes, feminism and kinky velvet shirts. This trick allows black-and-white to regain a status of possibilities as mere colors of the palette. In relation to yellow and purple any color is cast into a process of redefinition and re-evaluation. Painting as such turns into an experimental scheme, less as a means of representation, but a tool to probe communication, along the lines of inherent authority, institutionalized readings, ideological reflexes, secure meaning and safe points of view.

Kørner presents his work in scenarios that can be understood as carefully executed methodological constructions that stimulate the production of problems. Elaborate theatrical installations form the backdrops for his paintings in exhibitions, or he places his work on streets, in shops, next to public sculptures, on fishing boats for the reproductions in his artist books. In so doing, he attributes his paintings the role of actors, turning them into performers. The interaction that arguably occurs between the viewer and the painting in the gallery, or on the street, is the mirror image of the way that social interests play off the artist’s approach to painting.

Consequently one of his shows in Copenhagen was aptly titled “The Problem of Performing.” The painting is the problem, the message, the messenger, and everything else follows suit.