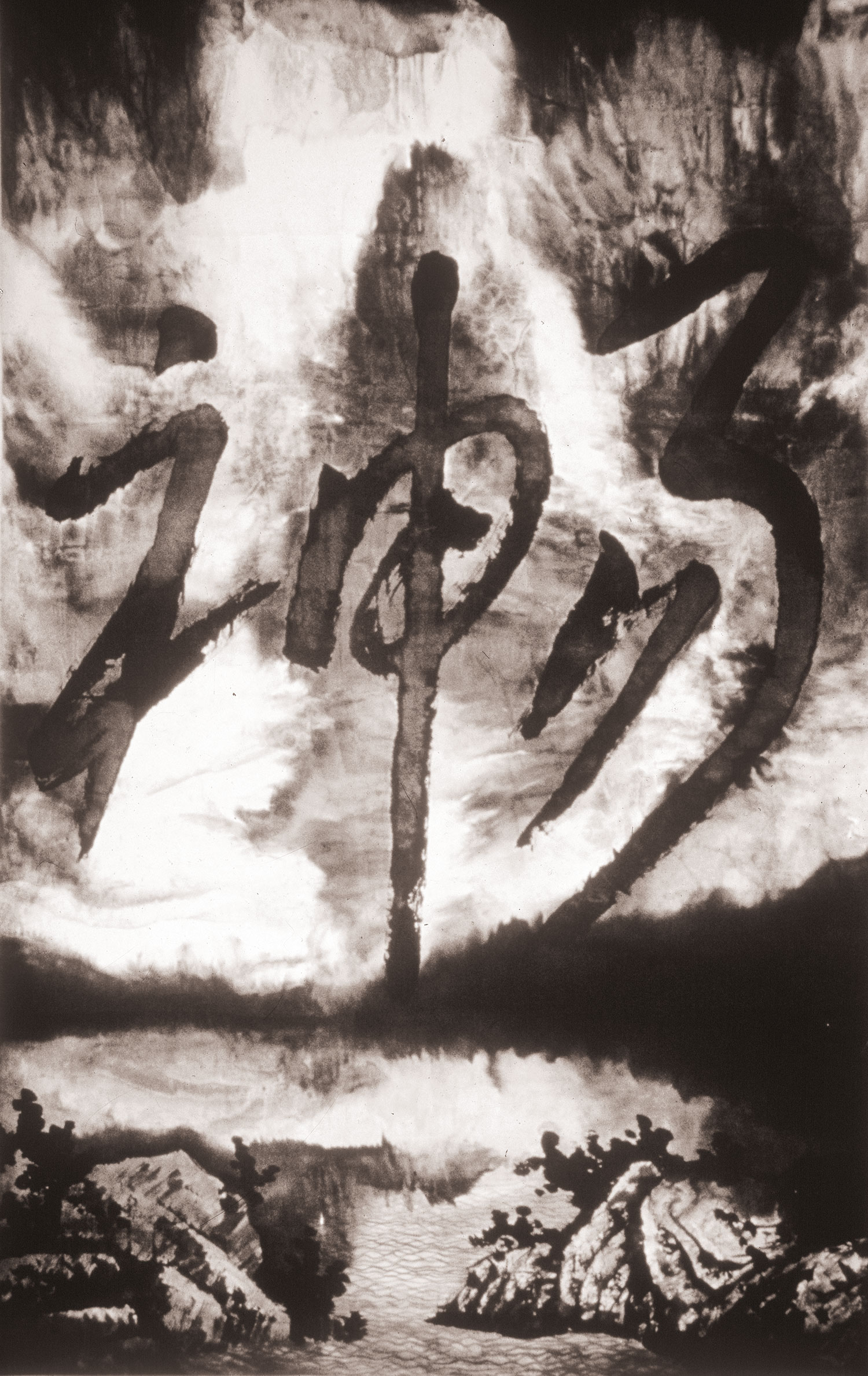

“Divine Ruse,” Jin Shan’s latest solo exhibition at BANK, in Shanghai, is a product of speculation and resistance. The exhibition leaves one with impressions of fear, trenchancy, and pain — not to mention admixtures far more complex and contradictory. A demoniacal scene is laid out: roughly hewn and frightful sculptural figures, one after the other, torn and fragmented, as though they were undead corpses in the barren wilderness, hideous and dejected. The gallery is transformed into a ruin imbued with memory, in order to present treasured fragmentary relics of human civilization, witnesses of its decline and rebirth.

Jin Shan selects famous sculptural masterpieces from periods of great cultural fruition — the Classical and the Renaissance eras — together with iconic images representing religious authority as well as Communist revolutionary idealism. The basic molds are primarily aids in art education for sketching practice, bought on the Internet; due to large-scale replication and reproduction, their original grace and spirituality have been utterly lost. At first glance, Jin Shan seems to aspire to the continuation of a certain lost tradition. Yet what he deals with are no longer simple, traditional elements but rather certain formal transformations and camouflages. He deconstructs and breaks apart these cultural symbols, attempting to create a world of images anew. This new world dispels the classic construction of the audience’s vision, instead exposing ambiguity and absurdity via endlessly embellished and distorted criteria.

In the artist’s view, ancient Greek civilization, Christianity and Communism all verge toward perfectionist explicatory or narrative techniques. Silver-tongued vindications embellish humanity’s endless craving, will to power and utilitarian impulse. What the artist interrogates, then, are the crises of power, desire, ethics and belief lurking under the grotesque and gaudy veneer. Hidden beneath the lofty trimmings of the “history of civilization,” a litany of savagery lies in wait. Reflecting the wane of human desires through ferocious and elaborate visual forms, Jin Shan’s recent sculptural installations bring forth an immense power rooted in the tense polarity between rigidity and fragility, thereby manifesting the futility of rationality and order. The sculpture Empty Net (2015) aptly captures a dejected mood, with a pair of sturdy shoulders forcibly crushed and torn apart. As the title suggests, the hand hangs down, plunging into nothingness, symbolizing futile effort and despondency.

Instead of considering Jin Shan a social-intervention artist, it might be more accurate to call him a skeptic. Skepticism is, moreover, an important tool in his observations of the world, and underpins a simple principle when coming to terms with his art. Jin Shan’s art has always revealed an alertness, an ambivalence, and a certain “lack of goodwill.” Early works, like Desperate Pee (2007) or Shoot (2007), among others, had already made visible his resistance toward customs, taboos and repression. The series of installation works thereafter, such as Retired Pillar (2010), It Came from the Sky (2011) and My Dad is Li Gang! (2012), are elaborate and large-scale interrogations of formalism, authority and the expansion and loss of control over individual rights. In 2013, Jin Shan created the “Bad Angel” series, with the mischievous Cupid as the artist’s humorous embodiment. Since then, his artistic style has undergone a change; it no longer directly and concretely voices concerns about the ills of our time, instead digging out latent spiritual substances veiled by the sheen of grand narratives. Jin Shan warns against pleasure in the production of concepts, seeking instead a solid expressive language by means of an experimentation in physical materiality that attempts to balance the disparity between personal perspectives and the disordered jumble of the world.

The plaster aids are remodeled and distorted by silica gel, taking form once again by pouring a particular plastic ingredient. The ultimate transformation of the sculpture comes about from the artist’s seemingly alchemical process: melting and pressing, pouring, soaking, slicing and cutting, tearing apart by adding in other materials like stone, animal fur, wood and the like. In Jin Shan’s hands, the exceedingly ordinary industrial material that is plastic displays a shocking destructiveness and explosiveness; it forges a labyrinth of images with its own inherent gravity and pliability; it breaks down clear, distinctive formal relationships and molds constantly renewed and yet charmingly chaotic monsters. In Underground (2015), a female head hanging under a T-shaped structure fuses violence and elegance. Marble-like skeins are embedded in the grayish taupe skin and musculature; most of the skull has disintegrated and split open, exposing scattered globes and minute threads on the inside — like planets and the Milky Way — and all the while her face still wears a mysteriously tranquil smile.

When beautiful things face destruction, a spiritual force slowly arises from the ashes. The emotive experience accompanying pain or fear, pleasure or surprise, becomes an indispensable element of Jin Shan’s oeuvre. Nowhere (2015) is based on the sculptural model of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros — here a tilted replica with a broken arm. The athlete’s body has disintegrated, while fragments of his countenance and of his torso take wing, away from the statue. It appears as though we are experiencing the instant of an outburst or the process whereby the soul exits the body. It equally recalls the execution scene described in the introduction of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish:

“…on a scaffold that will be erected there, the flesh will be torn from his breasts, arms, thighs and calves with red-hot pincers, his right hand, holding the knife with which he committed the said parricide, burnt with sulfur, and, on those places where the flesh will be torn away, poured molten lead, boiling oil, burning resin, wax and sulfur melted together, and then his body drawn and quartered by four horses and his limbs and body consumed by fire, reduced to ashes and his ashes thrown to the winds.”

Foucault reckoned that the body is the greatest site of politics and power, and that it is intimately related to the development of human civilization. However, in Jin Shan’s art, the body has been reduced to a shell, liable to be maneuvered and dominated. He does away with the fetters of the physical body, expanding the negative space and activating the double tension that resides in the body — collective control as well as individual liberation. Mistaken (2015) fashions an image of the Chinese worker, of infinite yet self-destructive power. Erected on a pile of sharp waste timber, a torch may be set to him at any time.

In Final Rays (2015), the animal samples and molds overlap and interweave; the effect is that of a donkey with its skin torn and flesh gaping. The donkey has collapsed to the floor; a mirror placed in front of it reflects its terrible state, dragging viewers into this pathetic scene. In the exhibition at BANK, on the walls to the right and left of the donkey, were the collapsed balcony of a pope (Collapsed Icing, 2015) and a distorted gothic church window (Solar Eclipse, 2015). With their soft hues and flabby forms, they seemed like a layer of dead skin on the human body, the fleeting, faint imagery completely at odds with religious auctoritas. This series of works peals out an elegy: with spirits dejected and redemption rebuffed, the sufferers can merely brave the pain, linger on their last legs and battle their own shadows.

Jin Shan’s current work implies cutting against the grain of history, thereby rounding off a complete deconstruction of superficial imagery and conceptual generalization. His technique of “skin-flaying” makes clear how the determination to destroy the image can heighten its power even more than the production of the image itself. The sundered visual experience is inundated with desire and violence, revelry and chaos. It is difficult to separate the subject and object of the image into self or other; like Zhuangzi’s parable — in which a man dreams about being a butterfly and, upon waking, can’t distinguish whether he had dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly had dreamed he was a man — it is neither one nor the other, living life out in a floating world of mayhem and bedlam. In Narcissist (2015), two heads with deep abyssal faces gaze upon one another. Yet a narcissist is never able to see himself with clarity. Is this nothing more than the portrait that our culture breeds, broods over, and resists?