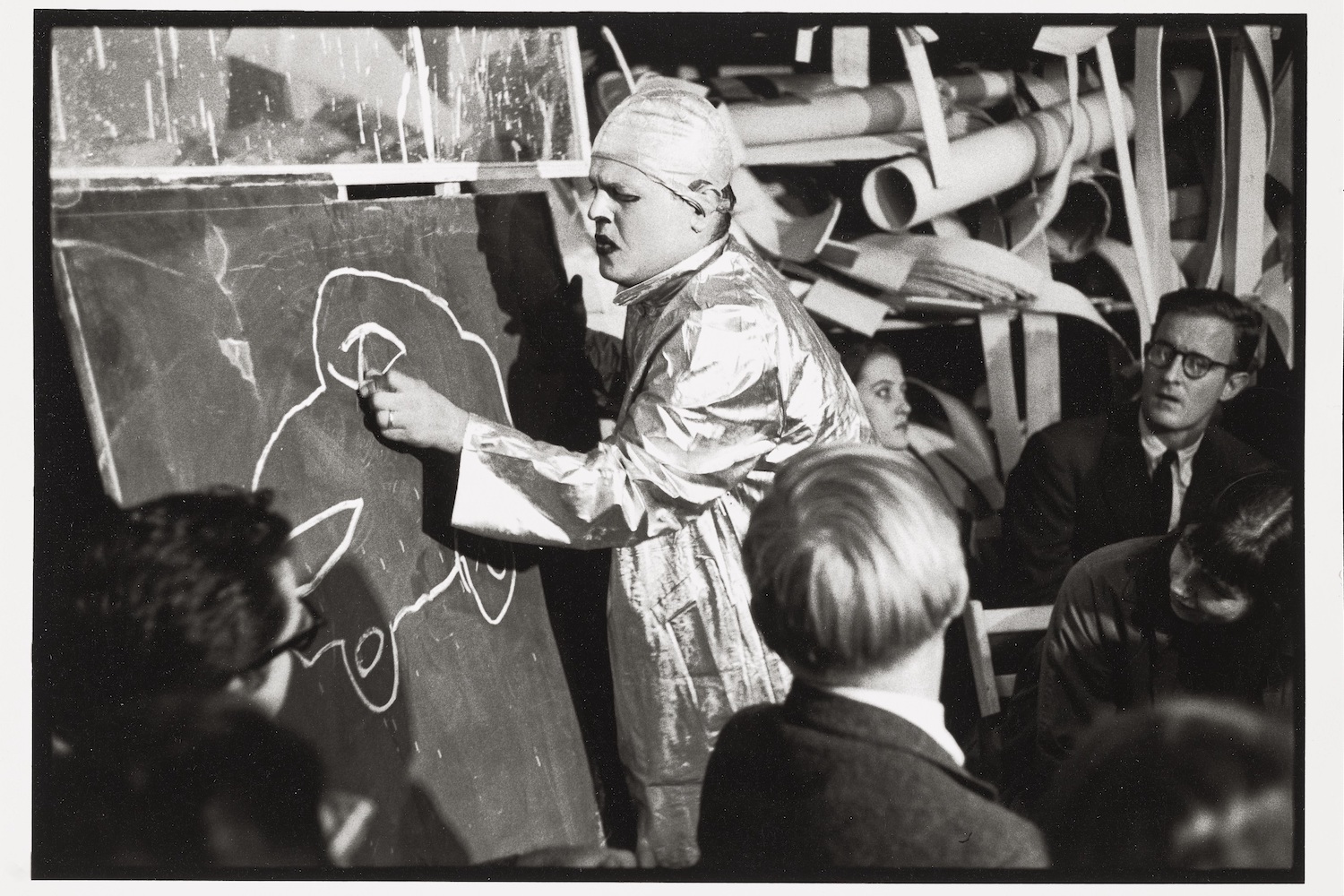

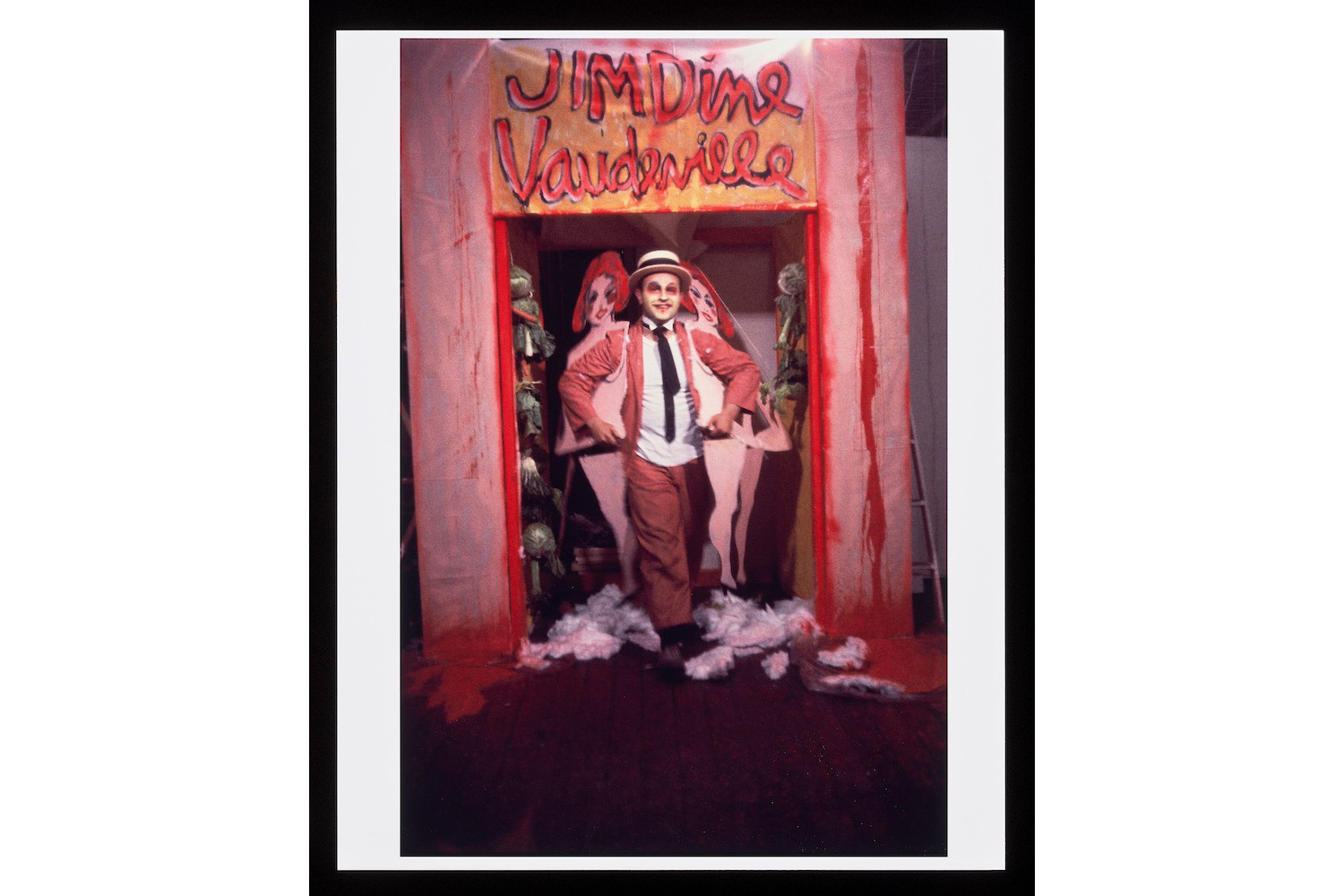

In a 1966 film directed by Lane Slate and Alan R. Solomon, Jim Dine, with a downward gaze and the attitude of someone who had already tired of the New York art scene, in one passage declares his complete trust in objects, in the way they exist together. After passing through the first room of Palazzo delle Esposizioni’s large survey dedicated to the artist, I confronted that film. Those words, “I trust objects so much, I trust disparate elements going together […] I think anything goes next to another thing; it’s just what you bring to it,” were epiphanic. They are also key to understanding an exhibition that traces Dine’s entire career, from the early self-portraits Head and Small Head (both 1959) and their implicit dialogue with the first environments and happenings, from The House (1960) to A Shining Bed (1961), or the final performance, Natural History (The Dreams), in 1965.

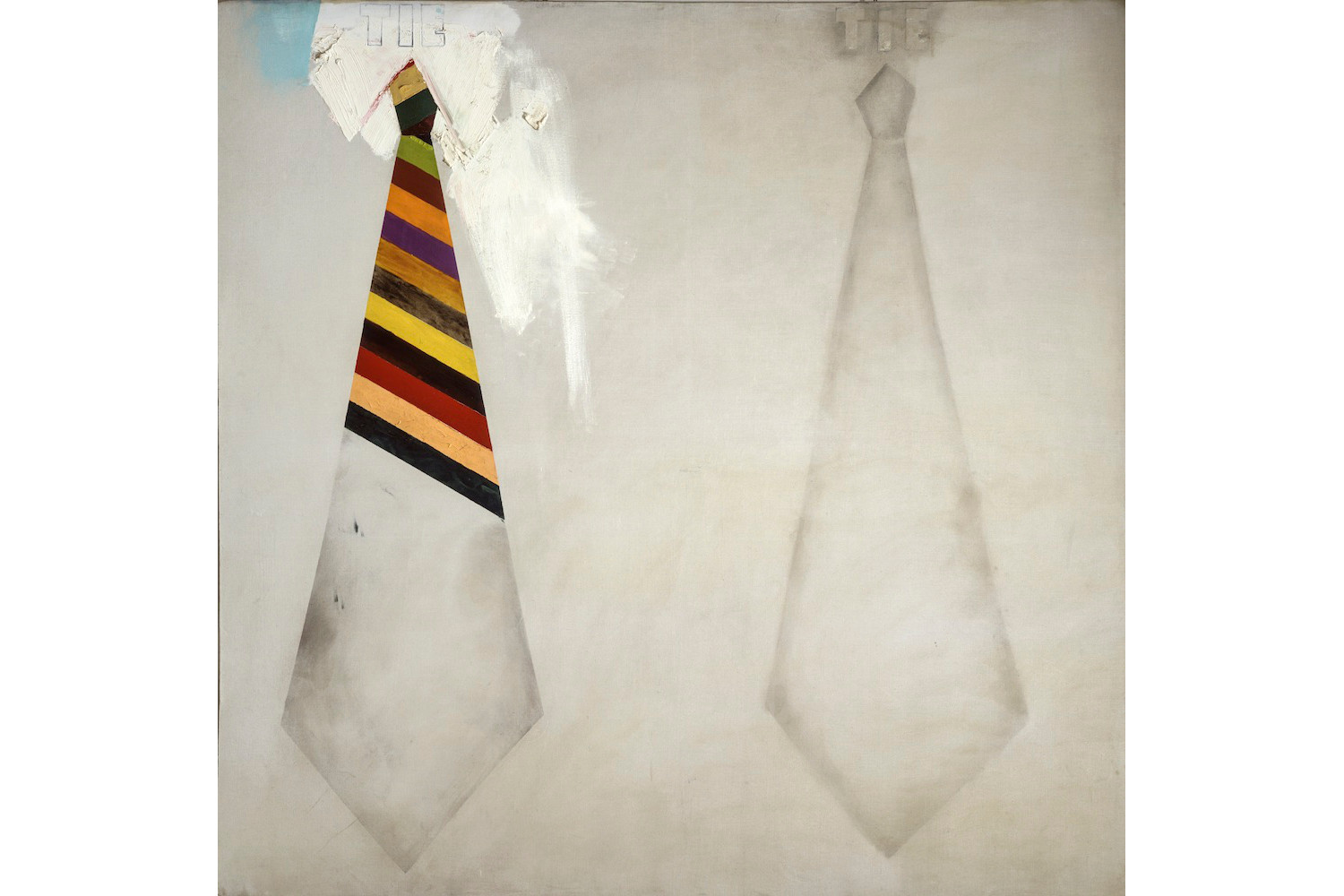

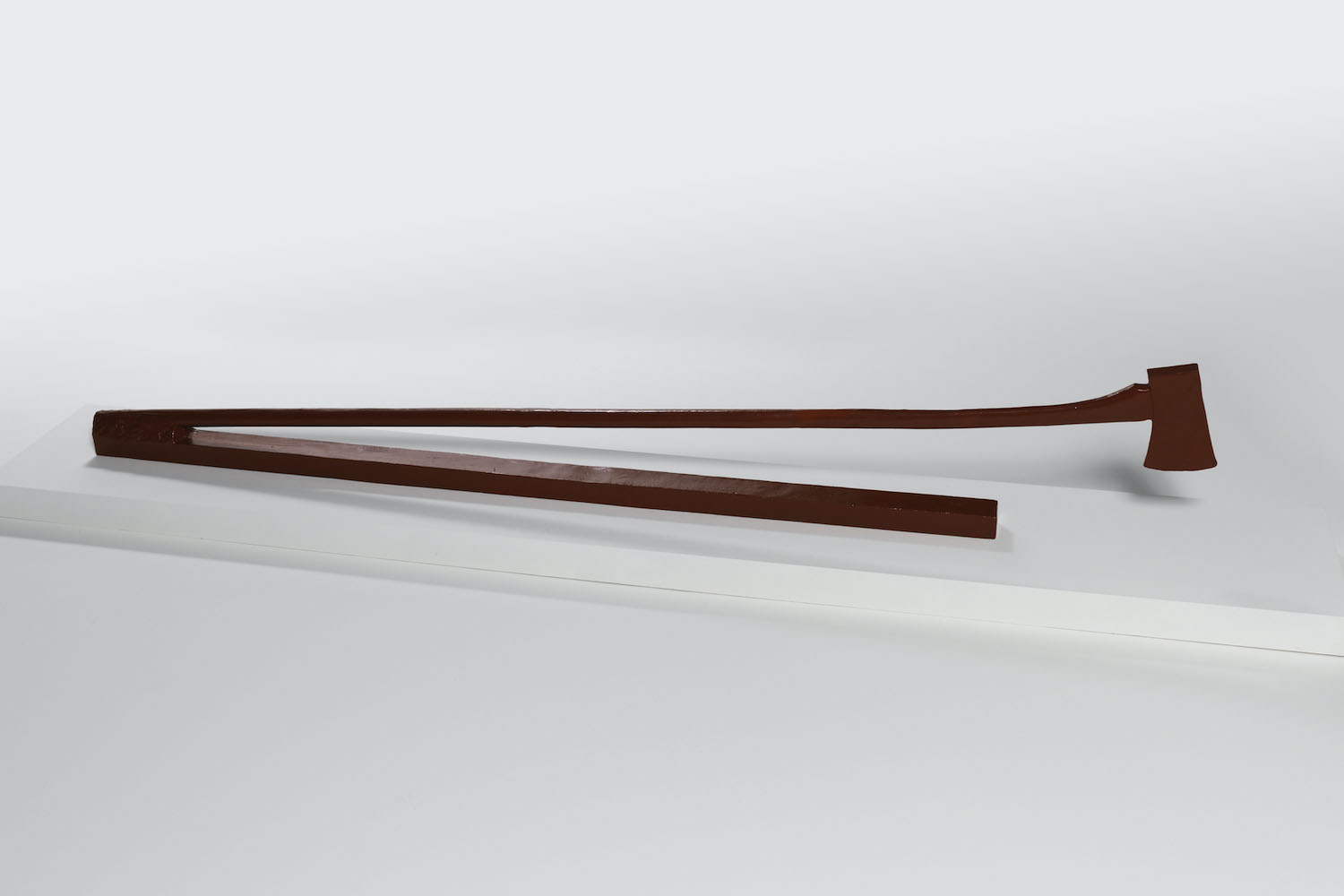

An extraordinary connection with the 1960s art scene in Rome is quite tangible in the second room, where works such as Black Shovel (1962), Window with an Ax (1961–62), and Two Nests (1960) recall Kounellis or Paolini, particularly their rigorous, almost sacramental approach to incorporating an object within a space (whether it be on the wall or on the floor). In the same room, works with painted objects accompanied by the word that describes them are both obvious yet also at the mercy of the spectator: Shoe (1961) is precisely a shoe, just as Tie Tie (1961) represents two ties — an attitude that echoes Picasso’s intentions more than Dine’s contemporaries Johns and Rauschenberg.

With the latter, Dine had in common the use of assemblage in exploring what occurs between the “literalness of the object and the mystery of the story of a comedy of waste,” as Francesco Guzzetti aptly points out in the catalogue text “‘New Uses of the Human Image’: Jim Dine’s Happenings,” which cites Lawrence Alloway — specifically the text that accompanied the exhibition “New Forms New Media” at Martha Jackson Gallery in 1961.

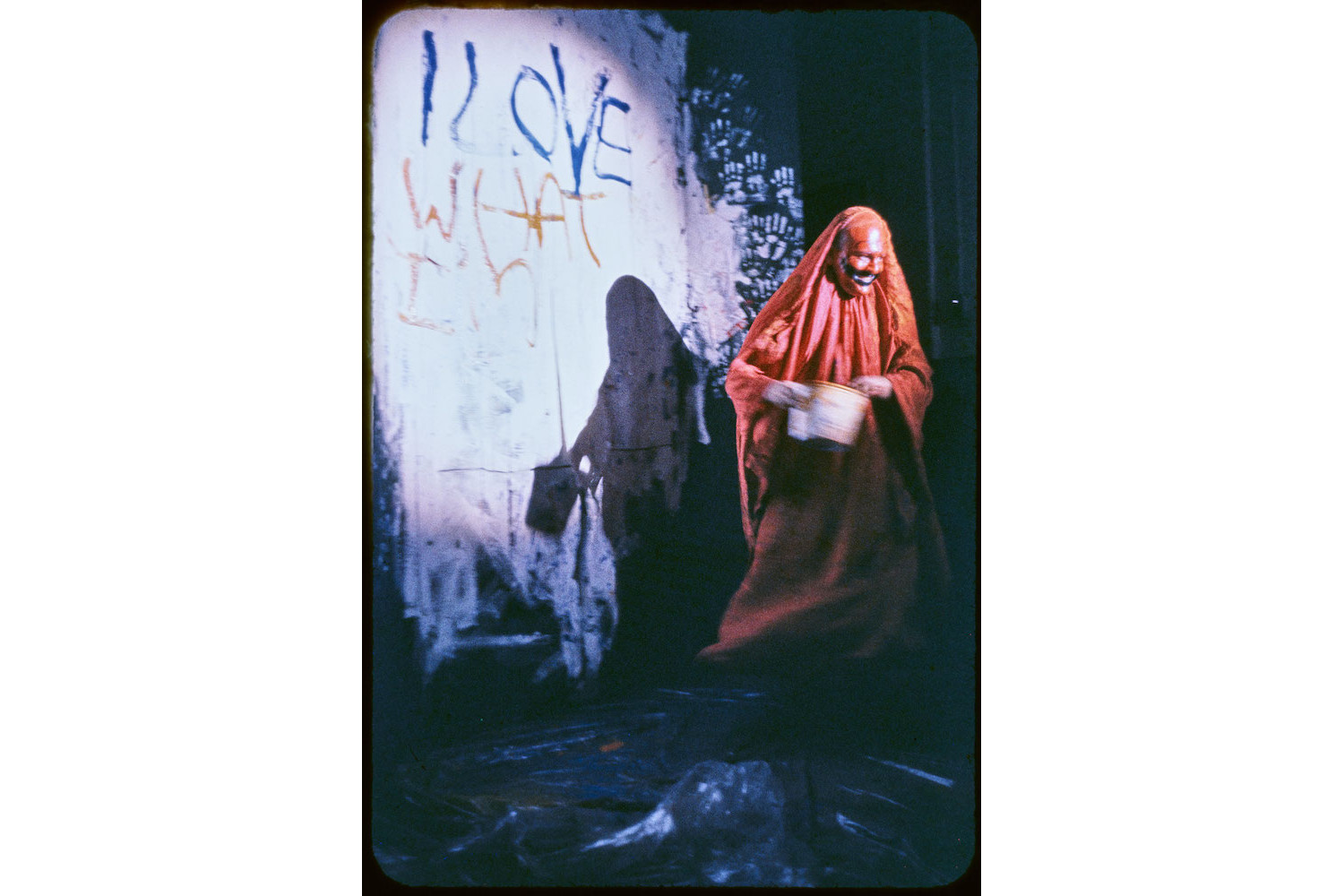

The self-referentiality that Dine transfers to objects is the same one that manifests itself when he becomes the medium — when he does not try to establish a relationship with the public, but instead limits his existence to his own dimension, that of the artist. (For example, in the last performance, aware of the reluctance of spectators, he stands in the center of the stage reciting his dreams in a nonchalant, narcissistic loop.) Dine’s objects merely exist. Sometimes they burst through the surface like the rainbow gutter that protrudes from the upper-right corner of Long Island Landscape (1963); sometimes they are extraneous to the pictorial surface, like the loafers that sit on the floor before My Tuxedo Makes an Impressive Blunt Edge to the Light (1965) — also reminiscent of Duchamp and Levine. Large Boot Lying Down (1965), a cast-aluminum riding boot, is another revelation in the exhibition, in the way that Dine places, modulates, and feels the object. Dine, like many of his generation, assimilated Duchamp’s lesson and tried to force it further — to re-situate everyday life entirely within the self and its production. The nature of the object matters less than the “pictorial” — therefore medium-specific — dimension through which it passes.