If the fantasy, or idea, of America presents an archetype of love-bombing, Jasmine Gregory’s work lays bare the seduction and emotional fallout. With stealthy appropriations of post-American Dream aesthetics (think: absurd excess, “quiet luxury”) the artist holds a mirror to the manipulation behind the pop-psych catchall, sustained by textbook promises of grand futures and patterns of withholding. In Estate Sale No. 3 (2023), corporate declarations of loyalty meet the appearance of “unmediated” expression in Ab-Ex-esque markings, superimposed with a tagline lifted from a UBS wealth management advertisement: “For some of life’s questions, you’re not alone / Together we can find an answer.” As if to say, “I’m the one who can give you what you want.” Unraveling the psychological remnants and control tactics in deadpan paintings and unruly mise-en-scènes, pooling on the floor in shreds of material like black-and-silver party tinsel, Gregory considers how that Dream preys on (and exacerbates) the fragility of being human, of our need for meaning and support through connections with others and the containers that are supposed to hold us. But Gregory is no scorned lover. Speaking in paradox, satire, and an emo-punk refusal, her work approaches existential questions in a mode of address that calls out contradictions felt within capitalism. Is it all decorating a void of our own making? What, if anything, is worth preserving from this world? What if it makes us feel better, for just a moment, to indulge in the fantasy of a better future that we know isn’t coming? Isn’t the glimmering limerence better than emptiness? “I am really interested in a certain lack of meaning,” Gregory explains, “and how we deal with this confusion, or lack, and just allowing the viewer to feel a sense of this discomfort, the fact that they just don’t know.”

In parcels of capitalism’s refuse and studio detritus wrapped in haphazard cellophane and ribbon, vitrines lit up like a sleek Dan Flavin fluorescent-tube-filled dance club, and quasi-modernist surfaces encrusted with glitter and meandering references as densely packed as her surfaces, Gregory materializes this party’s tangible allure and melancholy. It’s definitely over, but who was it for anyway? It’s hot-mess conceptualism and affective abstraction of the best kind, conjuring up an embodied chaos and alienation in the work’s internal structure, such that her use of contradiction functions to replicate the act of staring cognitive dissonance straight in the face but still coming back for more. Aptly titled, As a Dog Eats its Own Vomit, so Fools Recycle Silliness (2022) (a biblical proverb gesturing to flagrant engagement in a toxic cycle) is a satisfying amalgamation of ripped dry cleaner bags, baby blue ribbon, and paper hangers branded with the American flag that loosely resembles a corpse or deflated shell of a human disillusioned with the trappings of care. These kinds of visual one-liners are part of the materialtexture of Gregory’s imperfect appropriations: in forms that are at once insufficient and too-extra, cheeky and bleak and sexy, undetermined and slightly ill-fitting and barely held together, she relays an earnest reflection of how things really feel.

Thelate scholar and literary critic Lauren Berlant builds on a known concept of affective realism, whereby our innermost feelings create our reality (sound familiar?) and define the ways we are emotionally attached (often, anxiously so) to various forms of culture and politics and social structures. A helpful entry for thinking about Gregory’s work, Berlant’s term traumic is a primary example, referring to a genre of media in which a certain form of dark humor (visualized through opposing sensibilities) sometimes seems like the only option for coping with external traumatic events. Her interest in cliché, also part of Gregory’s vocabulary, looks at how smooth cultural tropes flatten individual experience but also offer points of connection. Likening her appropriation of capitalism’s various visual codes to the ways the avant-pop DJ and music artist SOPHIE (also tragically gone before her time) follows the pop song as a formula without subscribing her music to the complete pop fantasy, Gregory adopts cliché and hyperbole in a surreptitious mashup of autotuning imitation meets heartfelt self-expression. In sounding like the thing without being the thing while still inspiring love and obsession, Gregory’s work asks us to look at irony with sincerity, and at sincerity with irony, thereby interrupting the seamlessness with which we consume cultural products that, in the artist’s words, are “often vacuous but wield significant power in shaping collective dreams and social behavior.”

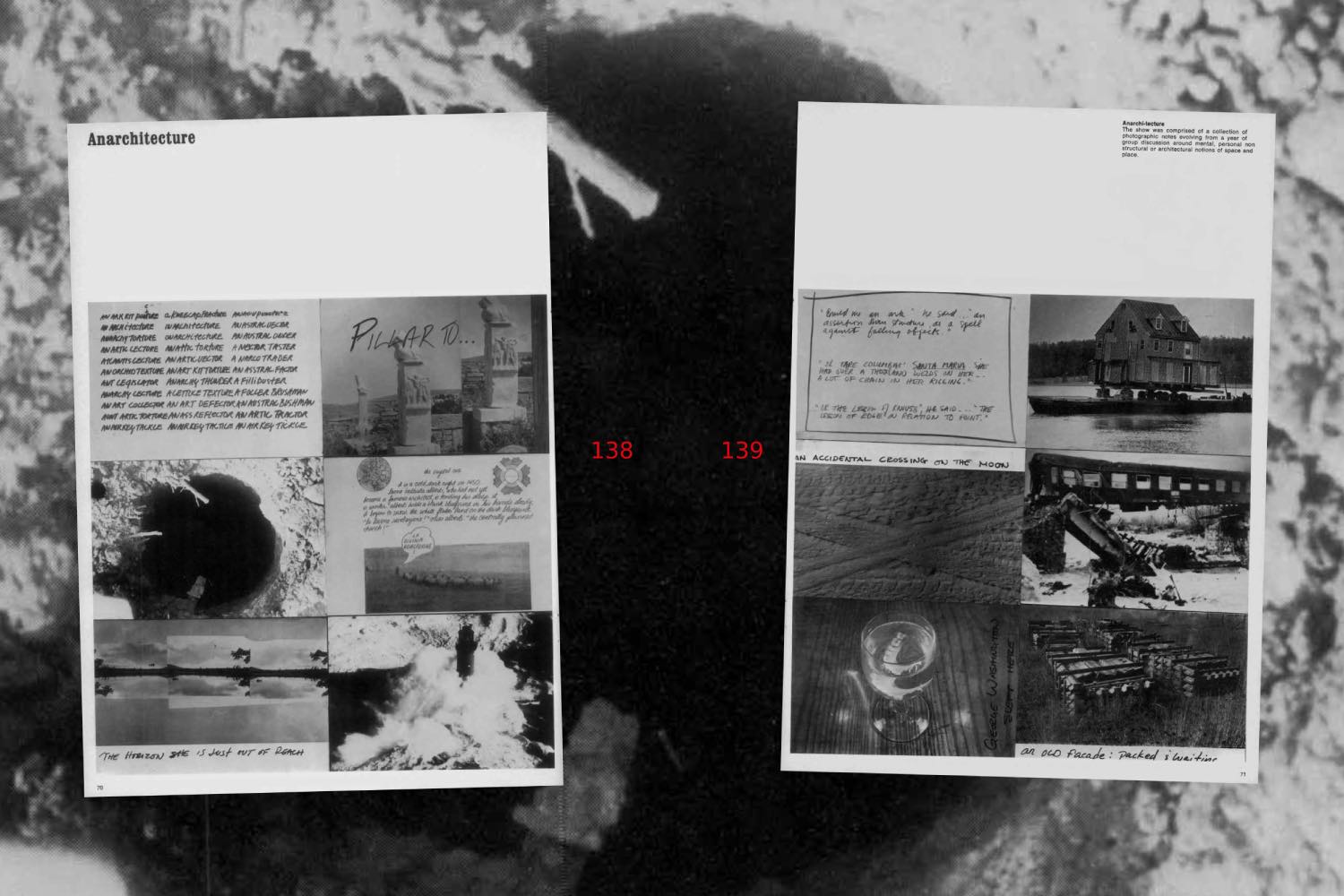

Motifs of said vacuousness, or the tangible presence of emptiness within ideas of ourselves, shaped by these products — and the comedy of it — run throughout Gregory’s work: in smudged and occluded text, empty vitrines and gift boxes, lots of transparent plastic, and finished wine bottles. “If You Are So Damn Smart, Why Ain’t You Rich?” reads a discarded yellowed ashtray in Counterfeit (2022), a floor sculpture of ajar gift boxes revealing the inscribed object and a sweetly crocheted handkerchief. In her 2023 show at Sophie Tappeiner,“A Little Newer, A Little Better, A Little Sooner Than Is Necessary,” a related floor installation of studio scraps housed in an orange Hermès box and other high-fashion packaging, alongside tiny irreverent abstract paintings unstretched like blotting cloths, resemble a field of provisional memorials. While reminiscent of Sylvie Fleury’s flashy deadpan designer shoeboxes and Isa Genzken’s anarchic consumer neo-junk assemblages, Gregory’s sculptures exude almost unadulterated nihilism, with a wink at the “end of art” but genuine sense of lost hope about what it can do in the world (and why it should have to).

In Gregory’s first institutional solo show,“If I can’t have it, no one can” at CAPC Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, lighting effects offer meandering puns on other forms of absence by way of projection and performance. As the artist abstractly transforms the galleries with the theatricality of a CNBC war room or unattended Olympics awards ceremony aglow in red, white, and blue, she seems to muse whether there’s some patriotic victory to celebrate. Highlighting the cavernous architecture, the spotlights accentuate the “nothing” that is here or that something is conspicuously missing (say, the intimacy and fulfillment and community that Nina Simone mourns in “Everybody’s Gone to the Moon” (1969), which informed the exhibition). “Eyes full of sorrow, never wet / Hands full of money, all in debt / Sun coming out in the middle of June / Everyone’s gone to the moon.” A similar tone of slight amusement accompanies other works in the show, including the “Estate Sale” paintings (2022–23) of UBS ads featuring white fathers and sons engaged in the proverbial passing of elitism’s torch of tying ties and passing down trust funds. Backlit with bright white, they contribute to the charade of how success and its social dynamics “ought” to look: from owning luxury goods to constructs of “Black Excellence” to Calvin Warren’s writings on Black nihilism, whereby the myth of “progress” only perpetuates America’s reliance on oppression at the core. What Gregory’s work shows us collectively is the ambient feeling of looking at what never was, or what it feels like when you subliminally knew that it was vacant from the beginning despite the sensory onslaught.

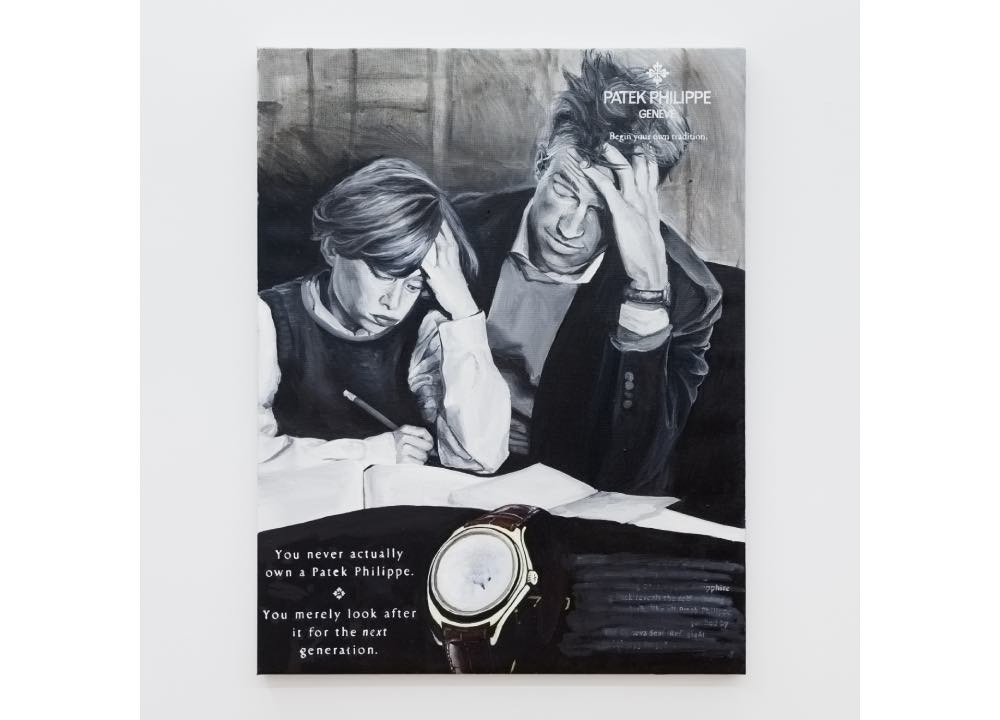

First shown in “Heirlooms” (2022) at King’s Leap in New York, are lated series of gray-scale painted copies of ads for Patek Philippe watches (starting price tag at the tens of thousands) expound on something adjacent to emptiness in the way of invisibility or hiding what capitalism doesn’t want you to see. In these representations of hollow familial love and occluded wealth, with lines like, “You never own a Patek Philippe / You merely look after it for the next generation,” father and son hug over financial exchange on a Marcel Breuer chair in a manicured living room or ride a private yacht in unbranded designer sunglasses. The watch is barely visible, epitomizing how inequality is hidden and, in being unseen, is insidiously maintained. In Investment Piece No. 05 (2024), we find our white male protagonists with gleaming smiles reading a book scrawled with the title Blood Meridian, referring to Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 riff on a Western genre about violent American expansion after the Mexican-American War. Advertising a wholesome inheritance of “values” of all kinds, these images convey an ersatz sense of nurturance in the performative vein of Richard Prince’s macho Marlboro cowboys. While Gregory’s tentative marks and intentional overworked-ness give “bad painting authenticity,” they simultaneously serve as a genuine assertion that the artist is here — even if constrained by historical and cultural constructs — and is witnessing this insidious fantasy with a knowing eye.

Gregory isn’t going to fold and give the system the transparent vulnerability that feeds it, but doesn’t point to a way out either. Often dangling, scattered, balancing, or abject, her paintings and abstract assemblages give shape to emotional fragility, but also the futility of artistic negation in forms that claim a certain kind of heroism: as suggested by False Gods (2023), a painting with a surface of dense black marks, glitter, and Jackson Pollock puzzle pieces. What distinguishes Gregory in a wider resurgence of postmodernism’s conversations and expression within abstract painting is her acknowledgement that our deeply felt emotions are so precariously tied up in — and, designed to reinforce — the idealizations that manipulate us, such that it’s almost impossible to keep them protected from becoming subsumed. “There are no solutions,” Gregory laments, “no morals to any stories.” In an eerie echo of these words and False Gods with its Pollock puzzle, Berlant writes on love:

Aggressions and tenderness pop around in me without much of a thing on which to project blame steadily or balance an idealization. So it’s just me and phantasmagoric noise that only sometimes feels like a cover song […]. I’m left holding the chaos bag and there is no solution that would make these things into sweet puzzle pieces.1

Gregory’s work resonates with such metaphors for how our emotions are intertwined in forms of culture and ideals of social structure via love and love-bombing, and seems to suggest two an play at this game. But in the face of real bombing, her work seems to ask: whatis a possible response? Gregory doesn’t portend to have an answer to how we can make poetry after genocide, inreferenceto AbEx’s raison d’être. Butshe bravely asks us to consider that cultural production cannot fix this.

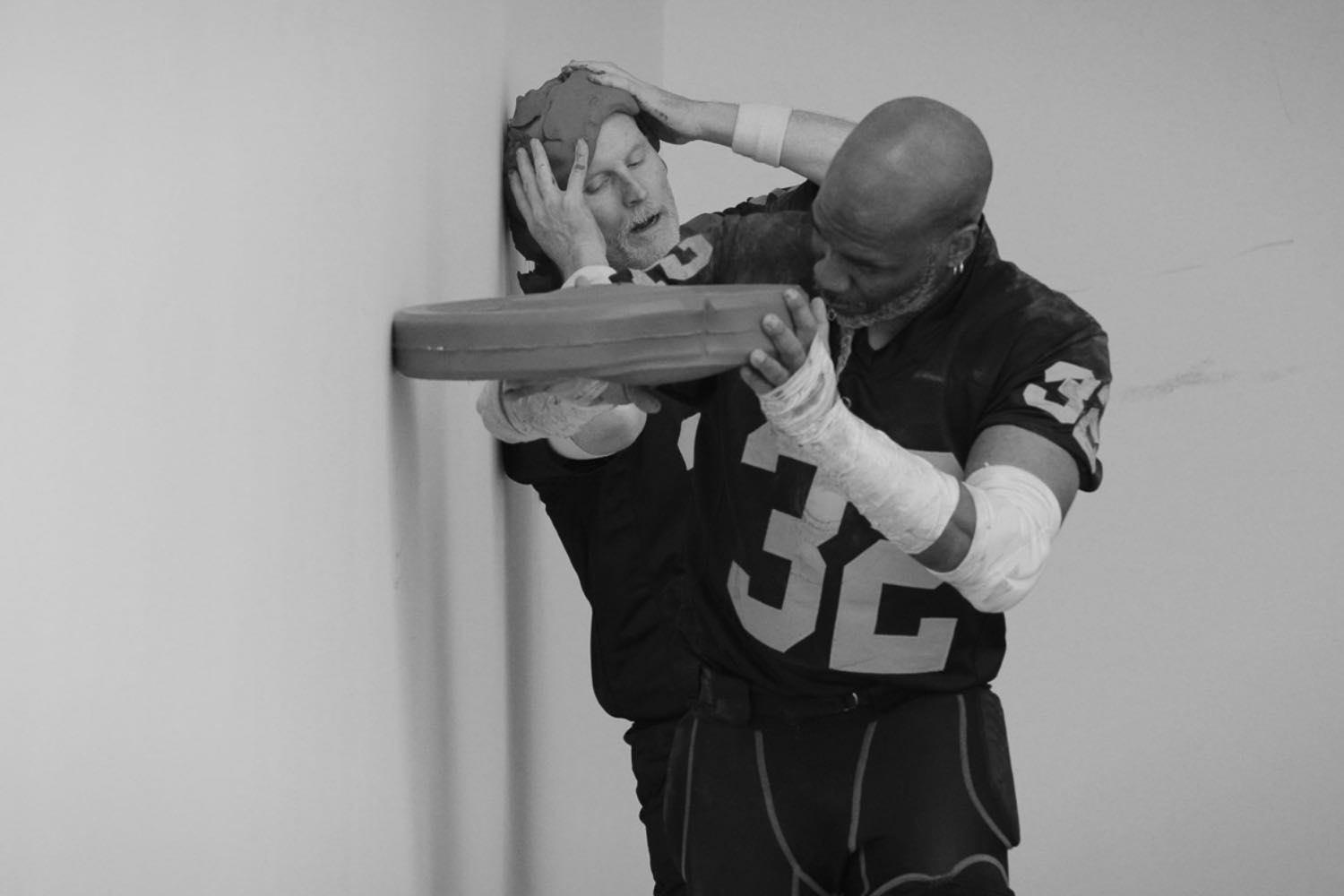

Gregory’s current solo show at MoMA PS1 in New Yorkresponds to this “spiral of despair,” in her words, drawing from Curtis Mayfield’s funk/soul song “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go” (1970),in whichhe describes the evils of looking away from humanity’s interconnected suffering and where that’s leading us. “But they don’t know / There can be no show / And if there’s a hell below / We’re all gonna go,” sings Curtis. The exhibition, “Who Wants to Die for Glamour?” (with echoes ofthe early aughts cultish gameshow Who Wants to Be a Millionaire), is equally invested in a kind of dark humor, evoking the virality and gamification of everyday life by suspending the viewerin a familiar vertiginous screen state with the gallery awash in a projection of swirling accidental iPhone footage of grocery shopping trips. A large glass vitrine mounted on the ceiling reflects the imagery and, separately, referencesa vintage Alexander McQueen ad campaign where the designer is suspended in an enormous tank. To quote Gregory on the purgatory of the artist, “Am I around the corner with popcorn or a participant?” In the show’s titular work, Glamour Shot (2024), a vintage photograph shows Gregory as a child and her mom dressed up for a Walmart staged portrait, a trope of aspirational middle-class shopping culture. Its valence nostalgia conveyshowsomething has been lost: the innocence of not knowing thatwe are embeddedin this fabrication, and thusdefined by it: as if we are fixed as individuals only determined by culture and historical circumstance, without our owncenter or core, and made to navigate the outside world accordingly.

They say the way to overcome a love-bombing cycle is to starve it out. No contact. Don’t react. Ignore. Ignore. Ignore. Delete. Gregory’s work does operate through negation, but it isn’t silent. At the conclusion of Curtis’s song, he emits a haunting shriek: “a sound that has always resonated with me,” Gregory shares. Maybe it’s the end, or maybe it’s an opening up of subjectivity to living with its inherent uncertainty and facing the questions of how we got here. By calling up despair and unknowing, she forces us to sit with those emotions rather than stuffing them down and seeking comfort from that which is hurting you. And by materializing emptiness and the something of “nothing” in her work, with a smirk or the pathos of being untethered, Gregory at least can crack open our inertness with a different frequency of sound.