A few years ago, when a colleague roughly ten years my senior asked what I was doing that Friday night, I said I was going to a Janus party at Chesters, and I asked if she knew of it. Yes, she told me, she did: it was where young people went to take horse tranquilizers and listen to terrible music. Though I liked the music, this was more or less true. Dan DeNorch and Michael Ladner started Janus as a club night in Berlin in 2012. For nearly two years, Janus hosted a monthly night at the otherwise nondescript Chesters, a dark and smallish club built into the corner of a Kreuzberg Hof.

Its resident DJs, Lotic, Kablam, and M.E.S.H., give Janus its style, a kind of club music I’m reluctant to define. Intuitively I can feel the parameters of what Janus does, but I don’t think I can put into words what happens inside of them. The namelessness of the kind of experimental club music Janus trades in — a genre loosely constellated, beyond Janus’s residents, around artists like Total Freedom, Arca, and Elysia Crampton — has generated a lot of bad writing, bad editorializing, perhaps speaking to traditional music writing’s deficit of language for talking about actually new forms. The music Janus disseminates is mostly danceable, sometimes not, and can really only be categorized as incorporating a wide range of social and cultural registers and having a taste for turbulence, maximalism and drama. At a Janus night, antagonism, too, can be a pleasure.

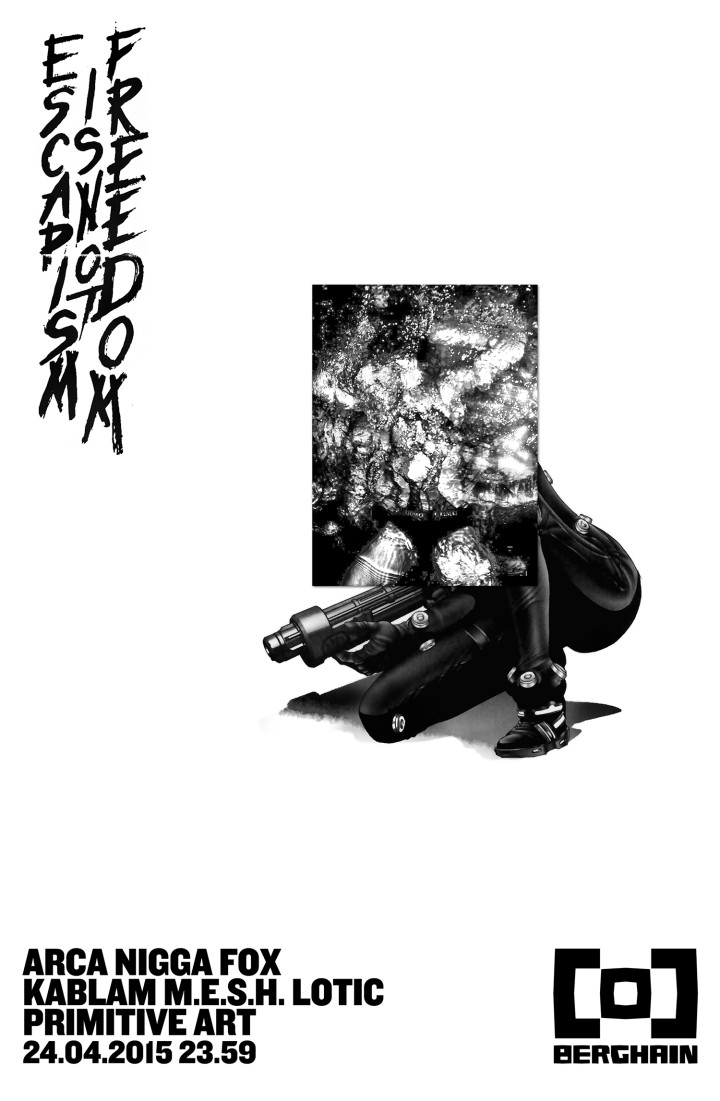

But like my colleague, a lot of people find the idea of Janus alienating, which is at least one metric of its success. Its popularity is another. Janus’s regular night at Chesters ended in May 2014, at a point when the space also seemed increasingly unable to accommodate the number of people it attracted. In its first two years, Janus had established a stable of regular collaborators, including DJs like DJ HVAD and Why Be; developed an informal network of like-minded record labels; and invited the artists who had been important to making this kind of music possible in the first place, like Total Freedom and Venus X. “I think what could be expressed at that scale had been done and I didn’t want to keep repeating the same thing over and over,” says DeNorch. “I feel like all the DJs and all the people I wanted to work with at that point I had had the chance to work with, several times.” Ladner’s involvement at this point became less formal, and Janus evolved into something both more structurally diffuse and more conceptually concise, releasing albums by Lotic, Kablam, and others, and organizing parties at more established venues and festivals in Berlin and internationally, the first of which was at Berghain later that year.

DeNorch comes off as a covert director, attentive to the ways in which a night might be designed, or how the lives and bodies of others are best served. “It has to do with space,” he tells me, and, with some hesitation, “with bringing something into existence that — in some ways — doesn’t have a right to exist.” An example: at that first night that Janus organized at Berghain, in October 2014, Lotic played a Beyoncé edit during his set. For all of Berghain’s claims to decadence or transgression, it’s a very white, very German institution founded on the idea that techno is underground and pop is mainstream and that maintaining these kinds of distinctions is important. Where does culture happen? Hearing Beyoncé’s voice in the “world’s coolest techno club” — among other wilder, unknown, deeply visceral sounds — felt like something that shouldn’t have been allowed. The results can be inconsistent, but if a Janus night is successful, the space can bear inconsistencies, make them look good, make them feel necessary.

Janus’s existence is perceived as an event. It doesn’t read as an organic development within Berlin’s nightlife culture, but rather like it’s imported from elsewhere. A few accounts have framed Janus as an example of Americans making the most of Berlin, reaping the spoils of rent control, changing the city’s social texture. Janus has received a comparably large amount of press, notably with an article in The New York Times in 2014, nauseatingly titled “Brooklyn on the Spree: Brooklyn Bohemians Invade Berlin’s Techno Scene.” DeNorch and Ladner are among a generation of Americans who settled in Berlin after college, as are Lotic and M.E.S.H. (Kablam is from Gothenburg). But a narrative of American cultural imperialism perhaps overestimates how closely Janus reproduces hegemonic Americanness. A lot of the artists Janus books are queer, a lot are people of color. Most aren’t American.

And while Janus’s specific brand of production happens in dialogue with an important American predecessor — GHE20G0TH1K in New York, which started in 2010 — it would be untrue to imply that the kind of parties Janus organizes are significantly more commonplace in the US. If anything, both parties kind of invented themselves, something that’s especially visible in Janus’s ongoing structural mutations.

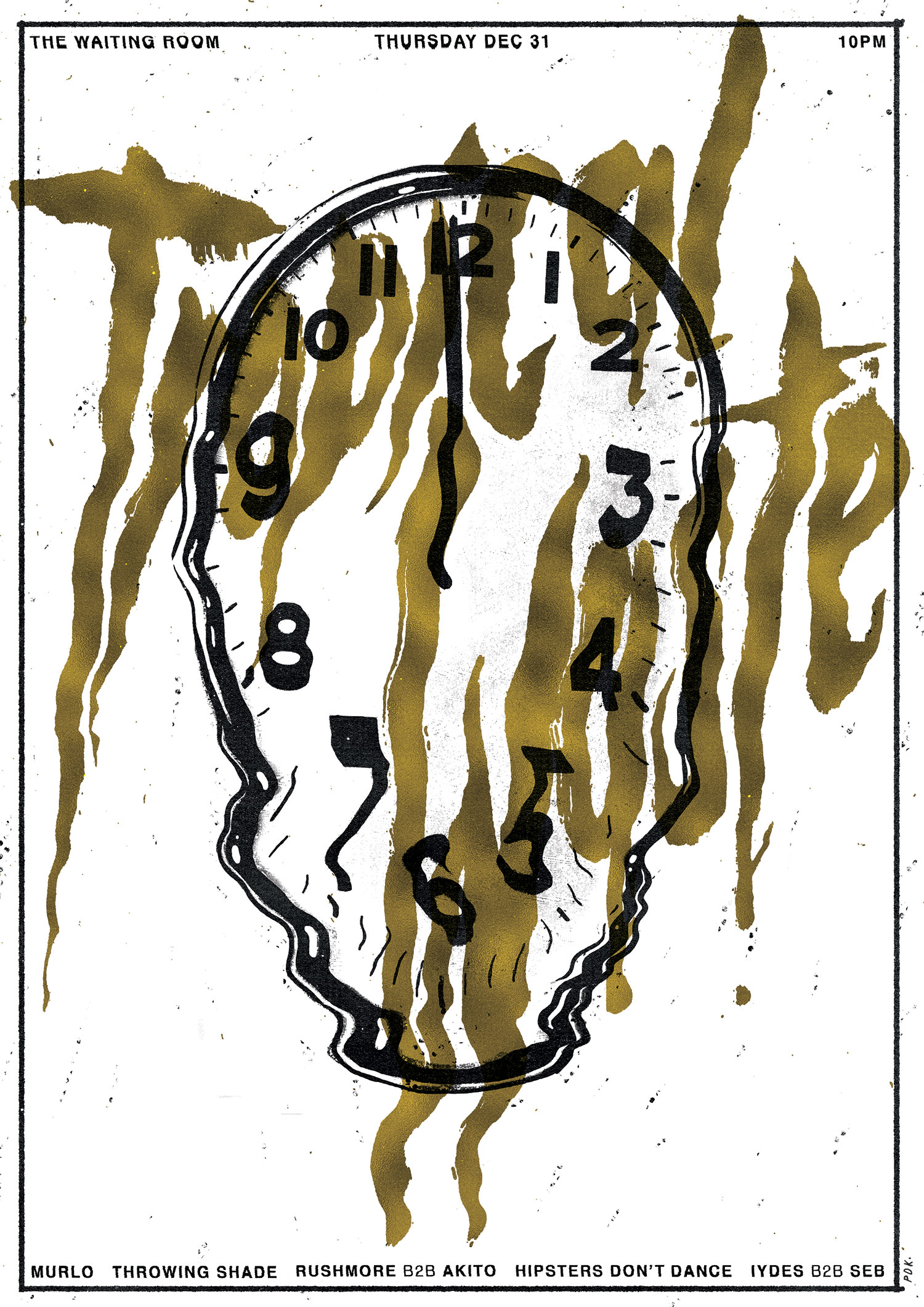

What can a club night do? In the popular register, club culture follows a twin narrative of utopic freedom on the one hand or depravity on the other. In my experience, however, either of these come second to expressions of community and experimentation. It’s not necessarily that there’s more permissiveness at a Janus night — or even more substance euphoria — than at another Berlin club, but just that that permissiveness is organized differently, and in a way that feels more fluid, more generative, and more relevant. Roughly six months into Janus’s tenure at Chesters, a small black-and-white icon of a capsule pill appeared on a poster advertising a night with DJs Full Effect, Felix Lee and Why Be, though in my experience the drugs to which it conspicuously referred had been a feature of the parties from the beginning. My own memories of these nights are inexact, some of them deeply unpublishable. In one I am crawling into a padded, short-ceilinged loft, the architectural legacy of the space’s previous life as a sex club in the ’90s. In others I’m dancing, or drinking at the bar. Art people are clumsily curling around a dance pole; someone’s hooking up in a not-very-private bathroom stall. Some parties I remember stepping out into a lightless Berlin morning, while others I don’t. It’s a kind of hedonism that’s fairly scripted, though at Janus it’s differently styled, more proximate to the art world. Janus’s embeddedness in Berlin’s contemporary art landscape tends to be the subject of some fascination, but more than anything it seems to me like a predictable and somewhat arbitrary result of mutual affinities and desires: clubs need tireless bodies, and artists need a social life.

A few years later, what Janus does now feels a bit more professional, producing more ambitious events with less frequency: club nights at both Berghain and London’s Corsica Studios a few times per year, one-offs at art institutions like MoMA PS1 and Palais de Tokyo, and other parties in cities around Europe. Its reach is wider, and the stakes, one feels, are higher. After having made space for itself and the producers it supports, what can Janus do? What can it upset, shift or make possible? Though Janus’s future remains to be seen, I get the impression that further mutations are yet to come.