Drama

Andrea Bellini: In “Categorie Italiane,” the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben asserts that one of Italy’s most important cultural categories could be identified in the anti-tragic component. You have lived in Italy since 1957. Do you think this argument is also valid for the visual arts?

Jannis Kounellis: I don’t know. The images I have in mind, let’s call them my images, were born during the Renaissance and the Counter-Reformation. I think Caravaggio, for example, is tragic. Or perhaps he is not a tragic artist, but he is surely dramatic. For me, this is Italy and these are fundamental references to being Italian. At least this is the way I have lived it, as a militant inside this kind of culture.

AB: But there is also a dramatic aspect to your work. Is this not true?

JK: Always. Because these are the basic foundations of my culture. The Counter-Reformation functions as the future, as a critical willfulness to build something new and diverse, to build a stepping stone to move forward. But the ancient always remains.

AB: What exactly is drama? Does it have a redemptive dimension?

JK: In Italy, wherever there is drama, there is a new perspective; everything new is dramatically new, the rest is not actually new. I’m thinking of Visconti and Pasolini, but also of Burri and of Fontana — all share a dramatic aspect. Also Sironi, for example, his borders, his idea of the labyrinth…

AB: Do you consider Sironi a seminal artist for post-war Italian art?

JK: Definitely. Sironi is a diapason. He gave Italian art a measure, and a starting note.

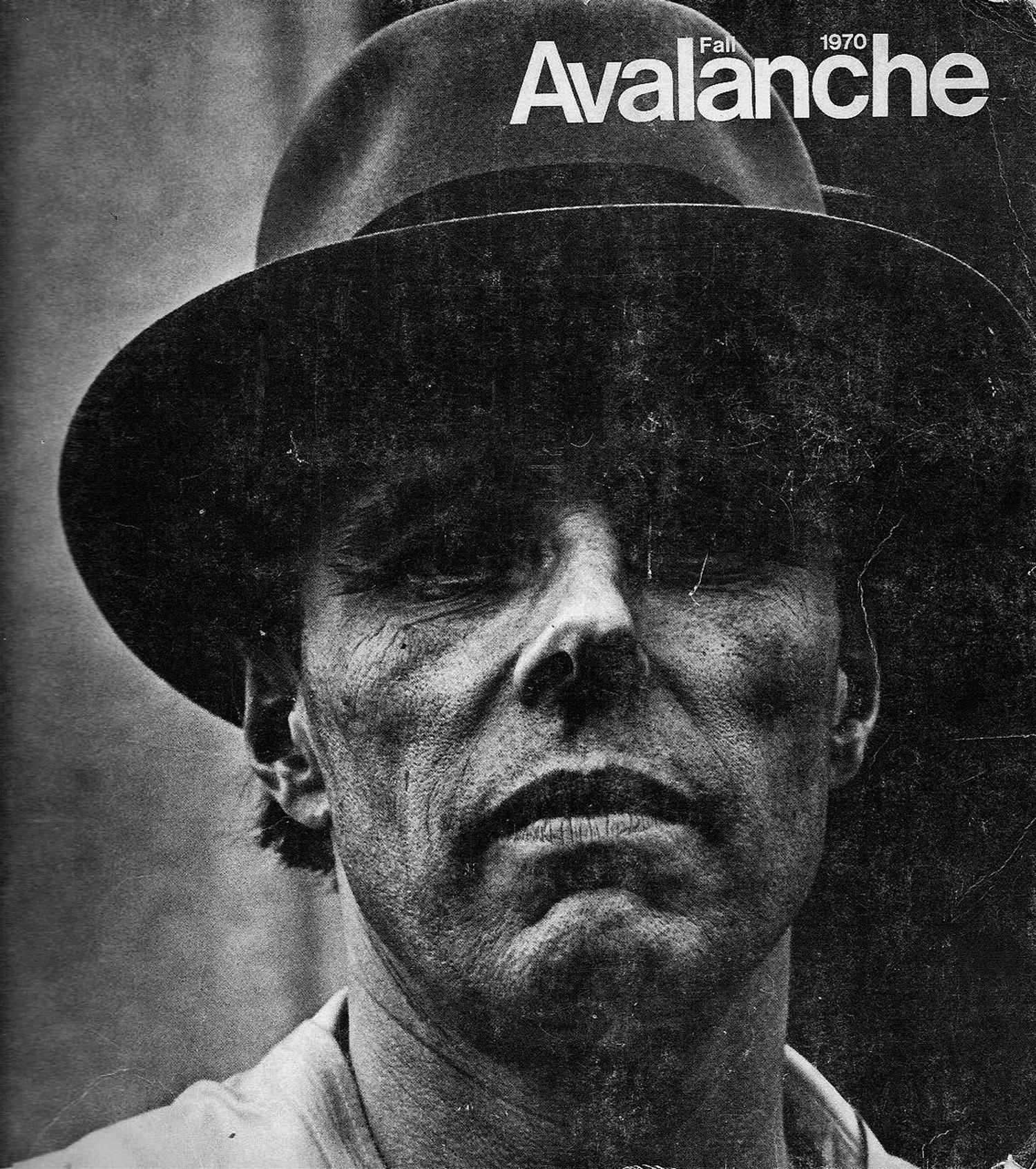

America

AB: In New York, Cheim & Read is showing your work. When did you first come to the United States? Who are the artists that you consider important?

JK: I came here for the first time in 1958, and perhaps I could have stayed. My father was living here and my grandfather was already an American citizen. But I came back to Italy. At that time I considered the European post-war reality much more demanding in a cultural sense.

AB: Which American artists do you feel are closest to your sensibility?

JK: I love Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline. I love that generation, because it is an epic generation, a generation that built a space, or rather that invented American space, ample and broad, far from the painterly tonalities, a surface that, in the best of cases, was lived with determination and radicalism. It is a generation that also eliminated the concept of the center of a painting. We have to say that, in a certain sense, we are indebted to this dramatic and idealistic generation, but certainly not towards the Pop group, who were extremely pragmatic and apologetic.

Language

AB: In terms of your personal research, what was your most important gesture?

JK: It was going out of the canvas, of the frame, during the ’60s. I went out of the canvas to have an open dialectic space. It meant for me going towards thousands of discoveries. In terms of freedom, this gesture opened a world for me.

AB: What kind of tension still motivates your research? Is there something you think you still haven’t reached during your long period as a working artist?

JK: Truly new things have never existed. And above all, this is what still pushes me to give shape to matter. My work, my research, takes form daily. This is the way I express my affection to humanism, a word that is no longer fashionable, but I’m not interested in being fashionable.

AB: What is painting?

JK: Painting is a logic. In this sense painting doesn’t even need a support. If this wasn’t true, we should think that Masaccio was simply a good painter. But in reality, Masaccio expressed a revolutionary vision of life and imagery. This is painting’s patrimony, and for this reason any ‘return to order’ is not possible.

AB: Which of your works do you consider particularly significant or important?

JK: I’d rather talk about moments. The word ‘work’ for me is something that goes from ‘nail to nail.’ There have been flashes of inspiration in my life, in which I felt true wonder in front of objects. As when, in 1966, I put a quintal of carbon in the corner of a room. I had this huge surprise of seeing a moment of freedom realized. I’m not talking about being liberal, but about freedom in a very ample sense. Through this gallery intervention, a space that, in truth, is public, I understood and felt the dramaturgic idea of art, the unique act of the gesture. Also in this case drama is never forgotten. Caravaggio is never behind us, he is our future.

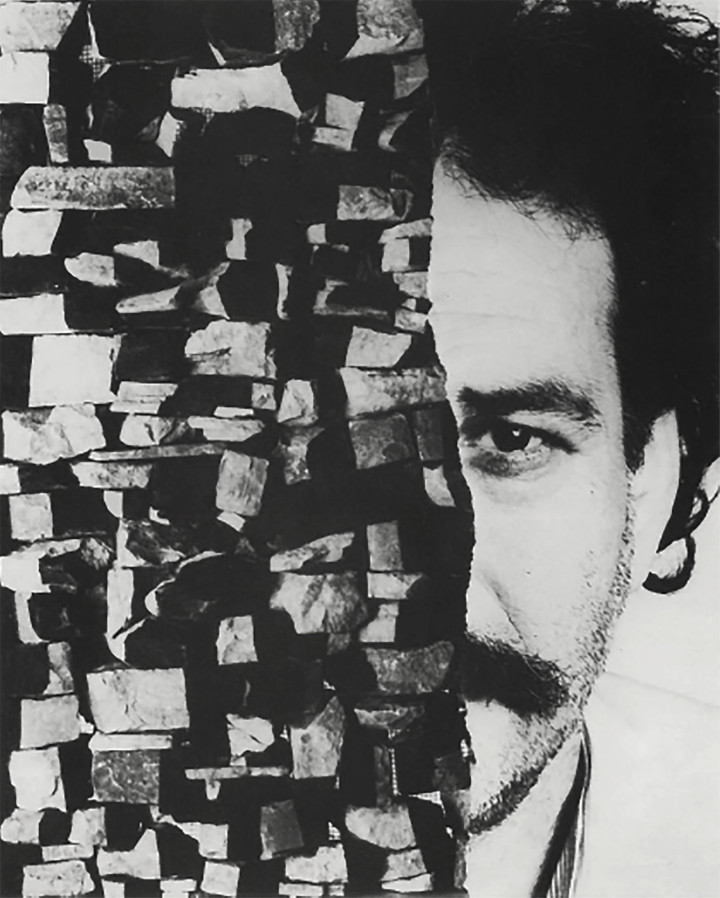

The Artist

AB: This kind of approach implied a deep change in the way to consider the gallery itself.

JK: Yes, exactly. This way to consider an intervention in a gallery changed the rules of the game. In this way, the artist began to take back a role that had been lost, and that had belonged to him since the Renaissance. The gallery can’t be reduced only to a marketplace. The intervention of the artist must be a statement, in a social sense. He can not simply be a virtuoso or a good craftsman.

AB: What deeply characterized your generation and, in particular, the Arte Povera group?

JK: Not having any dogmatic paranoia, not starting from a manifesto, the acceptance of contradictions. You know: having a dogma signifies the necessity for a defense. We didn’t need a defense because the premises were immediately realized.

AB: What kind of role could an artist have today?

JK: I don’t know, I have never been a modernist. But I live in Rome, and in that city you can easily see the role of the artist everywhere. Beauty is not aesthetically beautiful, beauty is subversive, it is a point of arrival and the artist maneuvers it towards one target or another. People shouldn’t forget that in Rome, in the Pantheon, resting among the kings of Italy is Raphael.

AB: What is an artist?

JK: He is an intellectual that is born and dies inside imagery; he doesn’t have novels to write; he doesn’t have anything except for the gift of the original illumination of the image.

The Human Being

AB: What about this show at Cheim & Read? There are some beds, some coats, some shoes…

JK: These are some works I recently did in Rome. There are some sheets of metal from which these ‘presences’ are hung. The measure is always the same as a double bed. I have always worked with these kinds of dimensions and relationships between things. I can’t exceed the height of a man. By now, it is too late to make bigger things.

AB: Also the choice of the dimensions of a work gives a sense of your humanism.

JK: I don’t want to forget the human being; I must not and am not able to forget the cultural coordinates that I received during my intellectual and human education and that push me to accept these borders.

AB: And this human being is perennially traveling…

JK: The greatest literary adventure, that of Homer, speaks of a journey that ends with a return, and this can be Ithaca as well as Dublin. One cannot leave this condition, that of traveling and chance. The return serves to codify the adventure.

Time

AB: Among contemporary artists, which seem to you to be the most interesting?

JK: A living artist is not necessarily a contemporary artist. I love the artists drawn to adventure, to renewal, those that do not ever accept evidence or obligatory data. This takes courage. Before, I spoke of Pollock and Kline because in them there is no sign of weakness. In certain cases, this pushes them so far as to risk their lives. If you are weak or fragile as an artist, your weight diminishes and becomes interchangeable and decorative. On an intellectual level, in general, work that is born from a weak area is intrinsically negative, in the sense that you are driven to accept compromises.

AB: So the trip exists solely in an heroic dimension.

JK: Yes, but I’m thinking of a Dionysian as opposed to an Apollonian kind of heroism.

AB: And is the past important?

JK: In Rome during the ’60s we used to organize large dinners with Pascali, De Dominicis and other artists. At the table, we spoke of certain artists from the past. Caravaggio, for example, was never missing from these discussions. Even when we discussed Pollock, someone would invariably bring up Caravaggio. The young artist that eliminates this kind of heritage understands nothing about politics and nothing about power.

Emotion

AB: Many of your works — I’m thinking of the horses in the gallery, the parrots, the works with fire or with lead — try to stir up an emotional reaction in the public, not simply an intellectual one. Is that true?

JK: Yes, because these things were born in darkness. All these images are of experience. If you subtract the emotion from these things you will not even find them anymore. Also this aspect seems out of date today, but I think it is still too early to consider this dimension superfluous. A very strong and original dogma would be needed to cancel the emotive, and I am the last undogmatic liberal.

AB: Is there something of which you cannot conceive of or accept?

JK: I cannot conceive of betrayal because betrayal is the starting point of all the gravest weaknesses. Betrayal is not possible.

AB: Betrayal in which sense? Of the work? Of language? Of friendship?

JK: All the serious betrayals. Betrayal stops the trip and the experience in an active sense. It brings you to the inevitable ‘return to order’ that, for me, is unacceptable.

AB: And towards what should we be faithful?

JK: We should be faithful towards the hypothesis of our boundaries.

Poetry

AB: To whom is this work addressed?

JK: You can work, or write, even for only 500 people. To be a poet for me means this. I don’t believe in this kind of fake cosmopolitanism. One can and must remain faithful, although not necessarily to a style. One cannot forget that the paintings we see in museums are, like the tip of an iceberg, representations of people’s emotions incised on the surface of a canvas.

AB: Is there a melancholic aspect in your work?

JK: Melancholy… What’s the name, I can’t remember, of this romantic poet buried in Rome, close to the Piramide neighborhood?

AB: John Keats is buried in the Protestant cemetery…

JK: Yes, him. His tombstone says: “Here lies one whose name was written in water.” In other words, if, early in the morning, you are able to create a credible image, melancholy fades momentarily.

AB: Speaking of tombstones, is the sacred still possible?

JK: Yes. The human being has its own sacredness. Painting a man is, without doubt, a sacred act, but cultural infiltrations are what give expressivity to the sacred. I believe that there are cultural markings even in the culture of the sacred. In other words, it is the chorus who demands the protagonist to be ‘of his time’ or assume this or that role.

AB: Jannis, today what could help us?

JK: Today, just as yesterday, nothing can help us. We need a great energy to re-establish the power of images.