Andris Brinkmanis: In your work there is a sense of alienation: strange, almost Kafkian or Dostoyevsky-like scenarios are represented, and imaginary elements that seem to be flashbacks from collective memory. The fact that you come from Latvia, ex-Soviet Union, also adds a possible nostalgic interpretation of your work. Would you agree with these notions?

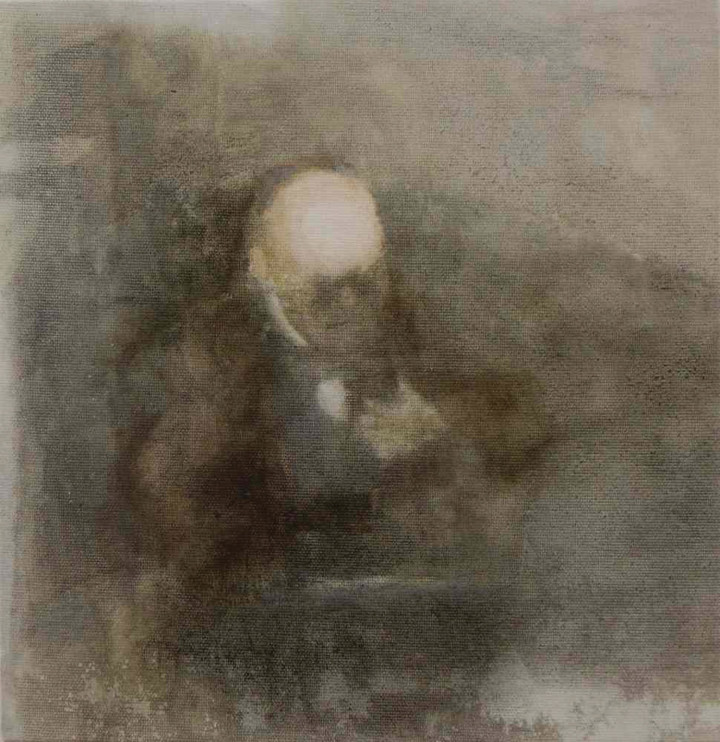

Jānis Avotiņš: Alienation in my work outlines the importance and fragility of a singular subjectivity , so repressed in our contemporary society. My pieces may seem soaked with this strangeness of our century, though not out of a wish to generalize. I am trying to cancel time and space coordinates in order to create a kind of anti-chronological, non-aesthetical setting in which this thin human condition can become visible. When representing a subject I try to purify the person, to erase all possible social identities, at the same time leaving the important presence of a personal history. I am not interested in subjects as nostalgic personalities, but rather they interest me as the absolute entities that have become part of our collective memory. Frequently, this notion of alienation may derive also from the way I represent the human face. Hands in my works are more in focus and recognizable than the faces. The human face in my opinion has too many signs of self-expression and is too intimate, thus losing its link with more generalized reality and culture. In the beginning of my career the selection of Soviet-like images might have been more intuitive. Later, it has become a way to reflect upon my background as well as a way to express my subjective and political position — a way to create settings and situations that would illuminate the gap between imposed, produced subjectivity and a fragile singularity. Probably that is where you may find parallels with the works of Dostoyevsky and Kafka. If we go more into detail, both volumes of paint and light in my work deal more with memory, with the most honest representation or “ drawing” of a memory intended as a symmetrical consequence of a desire. The selection process of the image is a crucially important part of my work, but the clarification and “purification” of the image during the process of painting or the so-called “technique” is also of great significance. Technique, at least in painting, in a way determines what kind of story you are able to narrate, to tell through the images selected. I am not using images directly in my work. I am redefining them.

AB: With which artists do you feel kinship?

JA: I feel familiar with my fellow Latvian-American painter Vija Celmins. Many subjects she has dealt with reappear also in my work. I have been always strongly influenced by the work of Jonas Mekas, Werner Herzog and Deimantas Narkevicius. Mekas’s film As I was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty has been one of the turning points that helped me a lot to become more self-conscious about the direction in which I would like to follow my work.