As much as an apt consideration about painting today would have been a welcome opening, there is an elephant in the room too big not to be addressed. Against one of the columns slumps a flaccid creature, a gastropod, if one has to be entirely accurate, but one blown up to an almost man-sized proportion. By its three-dimensional presence, it commands you to pay attention to the space around you. It is, to paraphrase Ad Reinhardt’s sally about sculpture, something you back into when trying to get a better view of the paintings. Here, however, the slug subverts the usual distinction between sculpture and painting. Made out of linen painted with acrylic and stuffed with bubble-wrap, it is a painting, so to speak, albeit an “unstretched” one — “Unstretched” is the title of the series to which it belongs.

In Jana Euler’s recent show “Unform” at Artists Space in New York, eight more of those limp, rust-colored sacks appeared to have colonized the building. One of them, strapped to the façade of the building, greeted the visitor outside, while inside, eight of its peers performed various poses interacting with the columns of the newly renovated space: slouched on the floor, resting vertically against them, or even forming circular, chandelier-like shapes suspended midair. On the walls, two conventionally “stretched” canvases, rendered in the artist’s favored hyperrealist manner, each represented another of those animals (Unform 1 and Unform 2, both 2018), here depicted as if moving full speed through a blurred forest background.

This configuration is a telling example of the way the 1982-born German artist’s practice engages with context through spatially constructed situations. Jana Euler is a painter, among the most challenging ones of her generation, but her paintings, before anything else can be said about them, are first and foremost social objects. The canvas does not open up as a magical portal into a parallel dimension, and there is no escape, no outside to this world. Her painting is immanent, entangled in a radical present tense. It is a social object submitted to the same gravity as any other object — just look at that slug’s heavy, tired body! And this is, precisely, its force. Whatever is lost in terms of contemplation and reverie is regained as engagement with contemporary discourse and reflexive criticality.

While all of Euler’s works are social objects, several of the artist’s recent solo exhibitions have engaged context through spatially constructed situations, confronting “stretched” painting with sculptural elements or wall texts. At Portikus in Frankfurt, where the artist’s show “In It” (2015) marked the former Städelschule alumna’s return to the town she studied in from 2002 to 2008, a monumental heart-shaped metal construction (titled the same as the show) blocked the entrance. Only visible once inside, the front side revealed a cartoonish face outlined in red on a shimmering background reminiscent of crumpled tinfoil.

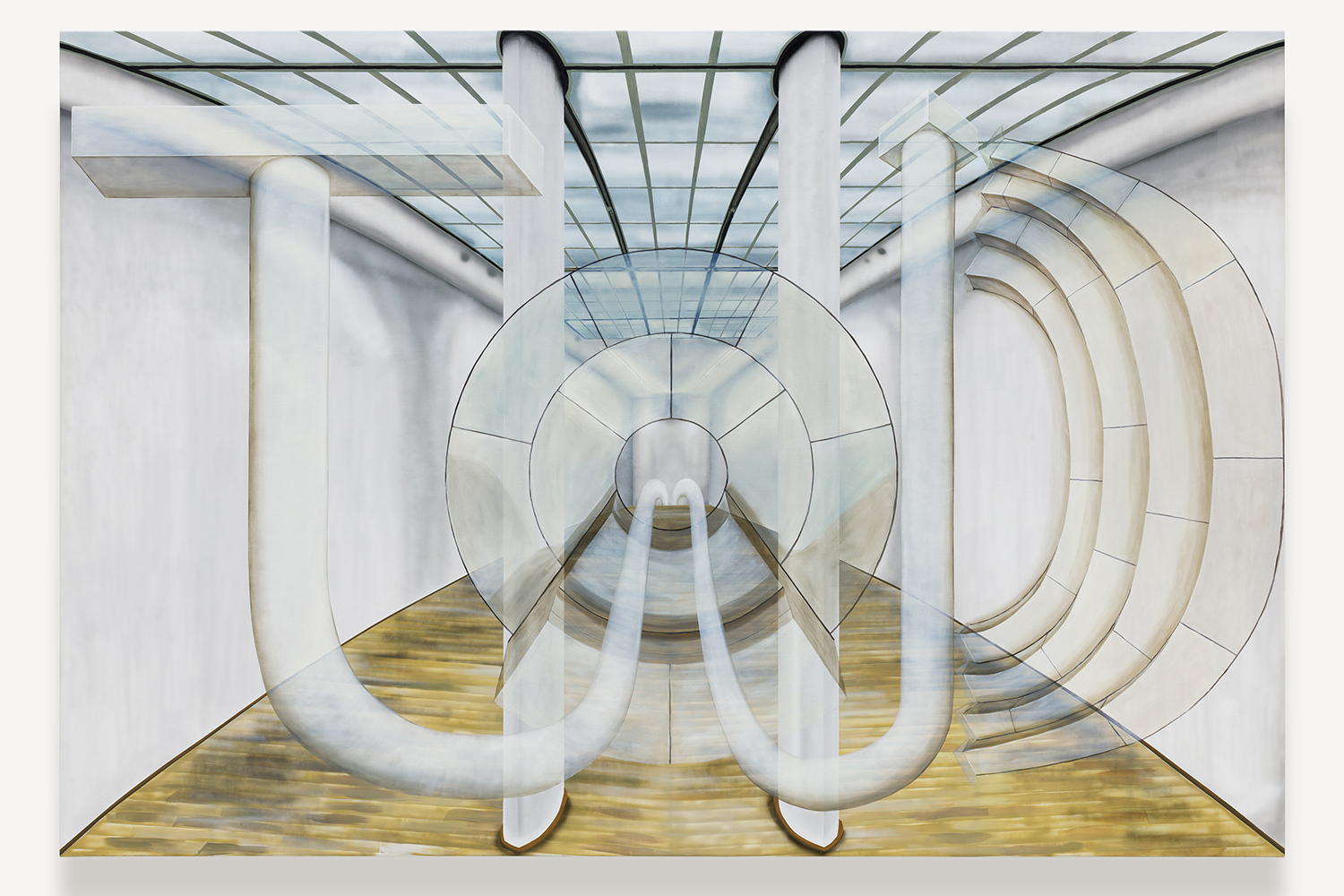

More recently, the artist’s MMK Triptychon (2019), included in MMK Frankfurt’s group-show “Museum,” played on a similar albeit more discreet viewing apparatus. Here again, two wall-hung paintings, a self-portrait and a mise en abyme of the museum’s architecture, were seen through a third element barring the view: a flat, white plaster board, almost seamlessly blending in with the walls, yet a hyper-stylized, almost architectural rendering of a woman’s spread legs. Although Marcel Duchamp’s Etant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau 2° le gaz d’éclairage (1946–66) naturally comes to mind — Euler’s works often assemble their meaning from inside painting’s history — it is not the sole reading of the work.

In conjunction with the other two works, the object asks viewers to take into account museums’ ideological biases, in this case gender, when looking at any artwork inside them. A recurring subtext in her work, like the heart-shaped face — which on second thought suspiciously starts to look like two breasts and a penis — the Triptychon and its leggy board reminds us that women in art tend to appear that way: as a naked body, represented by male painters, reclaimed by their female peers as a site of protest, but a body either way. The slugs from the “Unstretched” series perform a similar gesture of institutional critique. As is made clear by the titles, each configuration of slug and column enact tactical patterns that reflect those an artist might roll out to deal with institutional constraints: adapt (Unstretched, reform on), surrender (Unstretched, leaning, relaxed), lash out (Unstretched, ramming force), accept (Unstretched, bound, relaxed), critique (Unstretched, masturbation on column), ignore (Unstretched, outside mission), ponder (Unstretched, on couples).

Euler belongs to a line of painters working in the wake of the path opened by Martin Kippenberger and his entourage, when he insisted at the turn of the 1990s that painting should “visualize” its position inside a “network” — of friends, lovers, art-world relationships. This might have remained a mere background, one more father figure to kill, had the topic not been taken up again, and actualized, when David Joselit published his influential essay “Painting Beside Itself.” In 2009, coinciding with the artist’s first shows, he delineated a genealogy of artists that had developed their respective practices accordingly, all former studio assistants or collaborators of Kippenberger such as Michael Krebber, Merlin Carpenter, or Jutta Koether. He also went on to expand and requalify said networks, from then on also referring to the nascent digital infrastructure, “ranging from the impossibly small microchip to the impossibly vast global internet.”

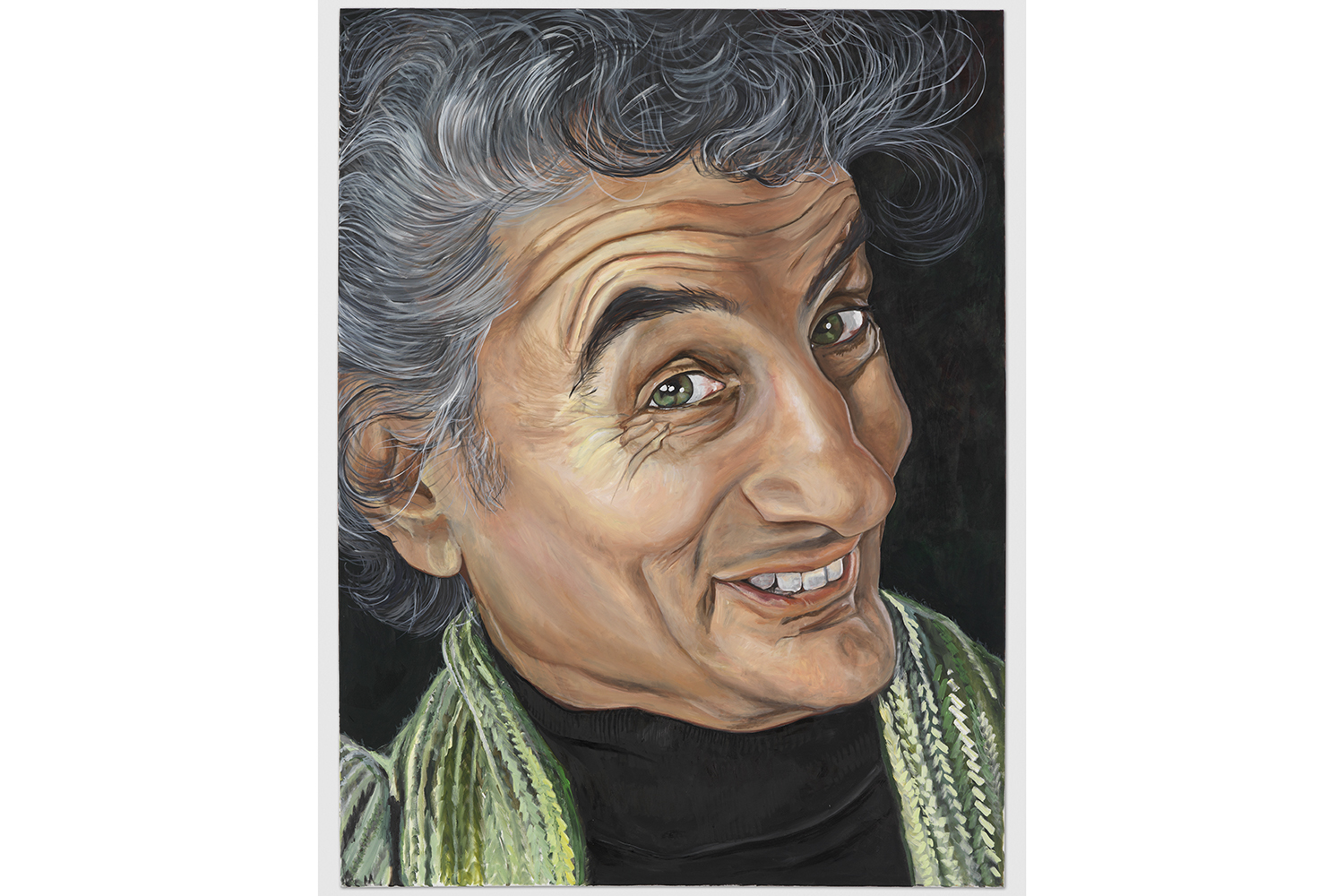

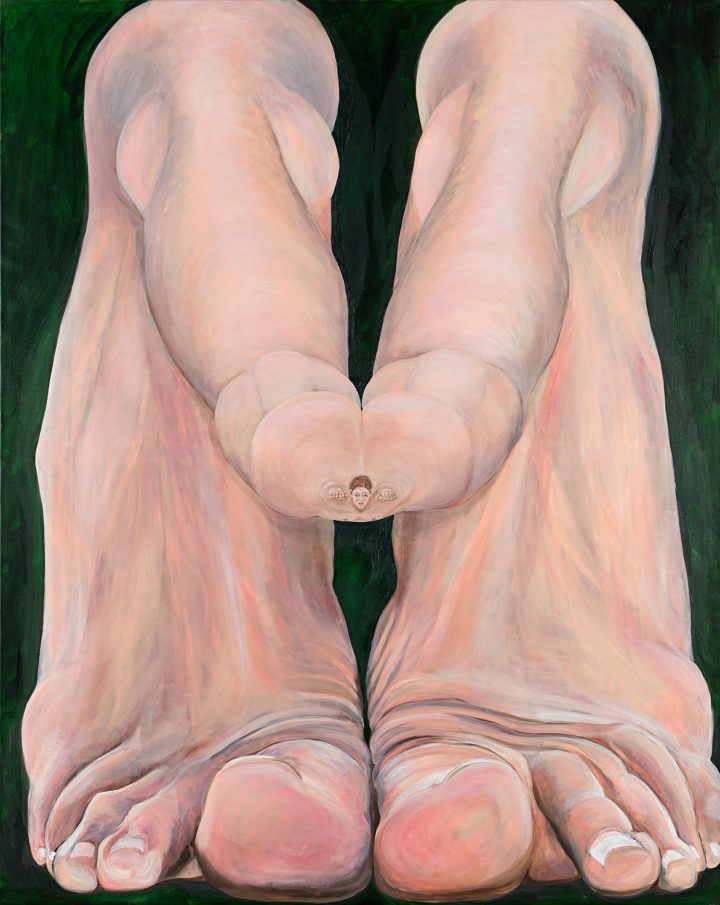

Because it has always been porous to its social context, Euler’s work has often been read in this light. Isabelle Graw’s 2012 portrait in Artforum quotes the essay as a frame of reference, but positions her painting as a critical take on Joselit’s “oddly positive view of the network concept” as it foregrounds “the vexations of the networked life in her exaggerated figurative deformations and repulsive flesh tone.” Deformation, but also collage, fragmentation, and multiplication, are all iconographical methods frequently used by the artist, especially when representing the distorted human body. While a tactical eclecticism in style and manner is the most representative feature of a practice that is impossible to circumscribe, the hyperrealist body, equally monstrous and grotesque, might be one of its most recognizable, intrinsic features.

In 2009, Euler grafted the head of an art-world celebrity upon the body of another (in works such as Ruth Suckale, Diedrich Ceccaldi, or Wolfgang Koschmieder, all part of the series “Ambition Universe”), which could indeed be read as a direct commentary on the imperatives of social networking. Then came bubbly heads filled with a variety of eyes, noses, mouths, and ears to choose from, as if it were a kit of fake nails (a recurring 2012 trope, as for instance with How to be more than one without turning Europe back to fascism). She more recently represented bodies folded around an empty center in her 2017 show at Cabinet in London (all four works titled “ ”, 2016). And then there is also the internet-famous Under this perspective (2015), in which two enormous feet each fold into a semi-erect penile extension, the two ends of which join into a tiny face no bigger than a pinhead.

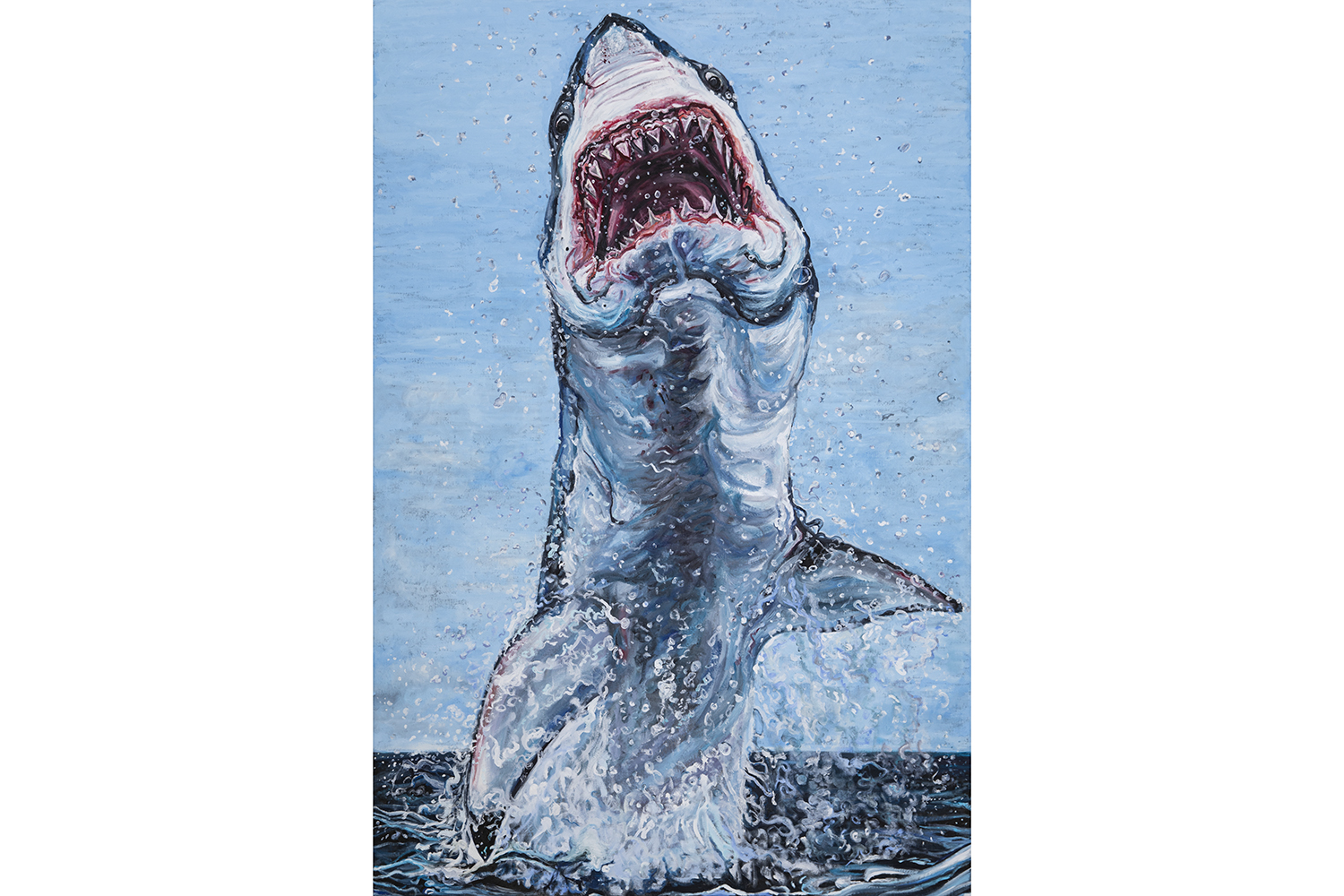

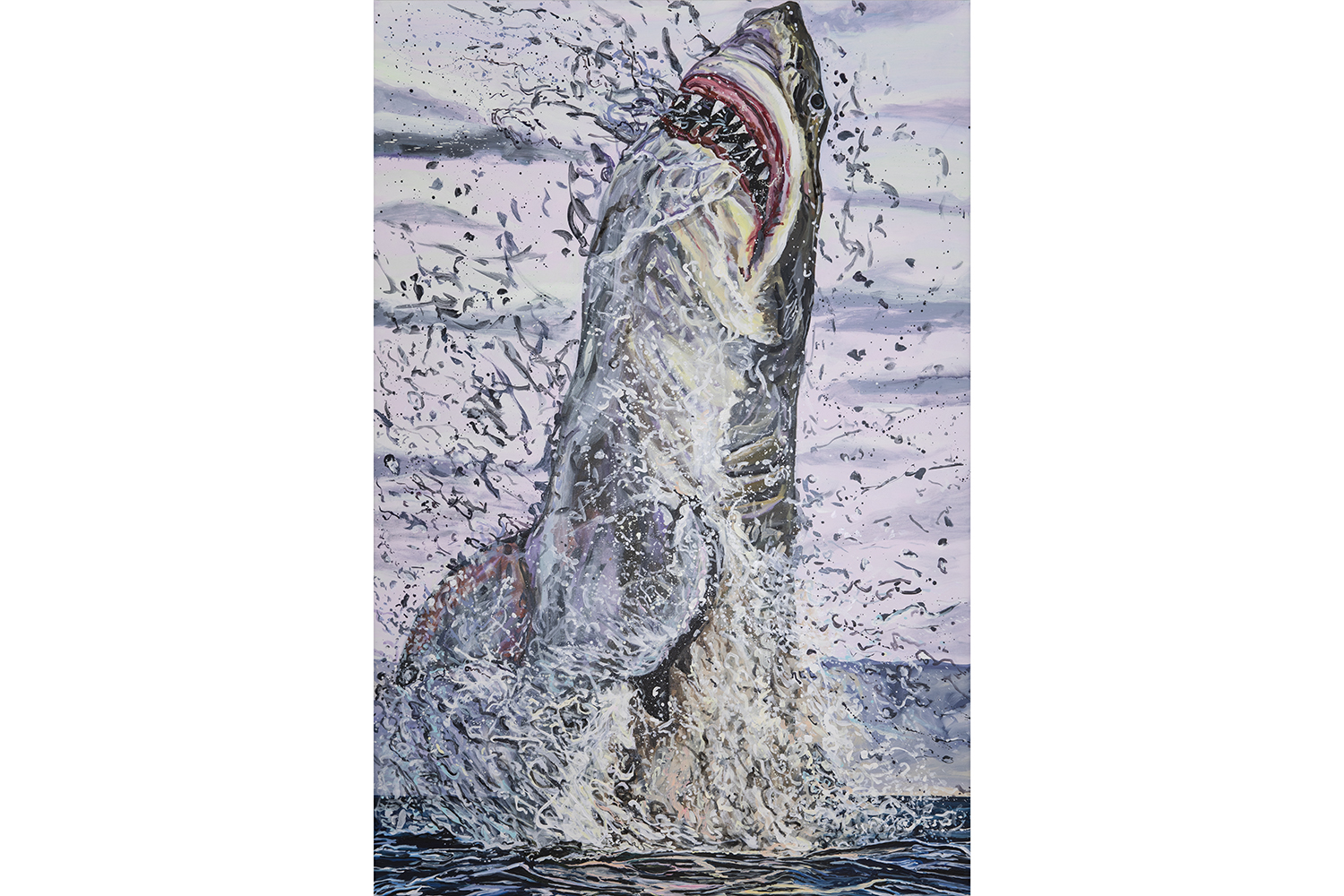

In Euler’s work, the human figure is under attack, and this is also its assumed unity. Even when there is no pink fleshiness as such, her work conveys a dizzying feeling that agency at all levels is failing. In her more recent works, animals have been used as stand-ins that embody the effective weight, felt and lived, of various power structures. This was the case with the apathetic slugs who adopted the shape dictated by their institutional environment, but also, recently as well, with a series of phallic sharks painted during the height of the #metoo movement. “Great White Fear,” her solo show at Galerie Neu in Berlin in 2019, was composed of only one type of painting — an hapax in her career. Each one of the eight monumental, three-by-two-meter canvases showed a single shark breaching out of the water like a vertically erect human penis. For once, one could even back up unhindered to get a better view of the spurting fish —a false freedom, though, since not much remained to be unveiled that was not given at first glance.

In a series that gleefully gloats over the fear of male white sharks — sharks that leap high over the horizon in a last-ditch attempt to escape imminent change — style and painterly ability were deployed in a full pyrotechnic display of the artist’s ability to paint in any possible way. While her figurative repertoire alternatively switches between academicism and amateurism, deconstruction and mysticism, hieratism and playfulness, the series especially concentrated on textures: thick splashes and smooth rainbows, voracious teeth and slick skin. However explicit the target, surface, not figure, was here the main focus, as further asserted by the variety of backgrounds displayed: a realistic landscape rendering, an out-of-focus blur, a pitch-black one, a psychedelic, op-art motive. While Euler’s paintings always are direct punches to the viewer, they do, however, point at a wider feeling that informs her work: a widespread condition of groundlessness.

Only a decade has passed and yet it now seems almost desultory to have thought that networks could represent the bigger picture. Since then, the manmade world has been uprooted, its triumphant infrastructures tossed around, its poststructuralist linguistic model of social relations drowned in an ocean of noise. We start to grasp that networks exist inside a world that cannot be mapped, that they were one last attempt at producing a totalizing narrative. Climate change and viral pandemics have progressively established in all minds that our world is a capricious, nonrational, and nonanthropocentric one with no center, leaving us with no stable ground to base the narratives that would make sense of it, politically or metaphysically. This is a self-evident fact to most contemporaries. We feel that structures are being uprooted, that formations are shifting.

This is the world Jana Euler actualizes by making fragmentation, eclecticism, and constant refocusing the structuring principles of her system. Inside it, conflicting realities exist side by side. It is a multifocal, nonlinear world, where only contingent and partial attempts at grounding can exist, and those have to be constantly updated — you squint, bump into an object, refocus again. You learn to look at it through the eyes of humans and non-humans alike, and get introduced to a world that can only be depicted as a non-exclusive one, as a plural site of cohabitation for multitudes. And yet, this is the world we inhabit and that we still have to deal with on a daily basis. It is from inside this disoriented present that Euler chooses to raise institutional and structural issues, having understood that our shared moment of metaphysical groundlessness is a political chance as well: now is more than ever the chance to overturn inherited, wrongful monopolies and built a new, polycentric world for equally fragmented individuals.