Anamorphosis

I will pass around something that dates from a hundred years earlier, from 1533, a reproduction of a painting that, I think, you all know — Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors. It will serve to refresh the memories of those who know the picture well. Those who do not should examine it attentively. I shall come back to it shortly.

Vision is ordered according to a mode that may generally be called the function of images. This function is defined by a point-by-point correspondence of two unities in space. Whatever optical intermediaries may be used to establish their relation, whether their image is virtual, or real, the point-by-point correspondence is essential. That which is the mode of the image in the field of vision is therefore reducible to the simple schema that enables us to establish anamorphosis, that is to say, to the relation of an image, in so far as it is linked to a surface, with a certain point that we shall call the ‘geometrical’ point. Anything that is determined by this method, in which the straight line plays its role of being the path of light, can be called an image.

Art is mingled with science here. Leonardo Da Vinci is both a scientist, on account of his dioptric constructions, and an artist. Vitruvius’s treatise on architecture is not far away. It is in Vignola and in Albertini that we find the progressive interrogation of the geometrical laws of perspective, and it is around research on perspective that is centered a privileged interest for the domain of vision — whose relation with the institution of the Cartesian subject, which is itself a sort of geometrical point, a point of perspective, we cannot fail to see. And, around the geometrical perspective, the picture — this is a very important function to which we shall return — is organized in a way that is quite new in the history of painting.

I should now like to refer you to Diderot. The Lettre sur les aveugles à l’usage de ceux qui voient (Letter on the blind for the use of those who see) will show you that this construction allows that which concerns vision to escape totally. For the geometrical space of vision — even if we include those imaginary parts in the virtual space of the mirror, of which, as you know, I have spoken at length — is perfectly reconstructible, imaginable, by a blind man.

What is at issue in geometrical perspective is simply the mapping of space, not sight. The blind man may perfectly well conceive that the field of space that he knows, and which he knows as real, may be perceived at a distance, and as a simultaneous act. For him, it is a question of apprehending a temporal function, instantaneousness. In Descartes, dioptrics, the action of the eyes, is represented as the conjugated action of two sticks. The geometrical dimension of vision does not exhaust, therefore, far from it, what the field of vision as such offers us as the original subjectifying relation.

This is why it is so important to acknowledge the inverted use of perspective in the structure of anamorphosis.

It was Dürer himself who invented the apparatus to establish perspective. Dürer’s ‘lucinda’ is comparable to what, a little while ago, I placed between that blackboard and myself. Namely, a certain image, or more exactly a canvas, a trellis that will be traversed by straight lines — which are not necessarily rays, but also threads — which will link each point that I have to see in the world to a point at which the canvas will, by this line, be traversed.

It was to establish a correct perspective image, therefore, that the ‘lucinda’ was introduced. If I reverse its use, I will have the pleasure of obtaining not the restoration of the world that lies at the end, but the distortion, on another surface, of the image that I would have obtained on the first, and I will dwell, as on some delicious game, on this method that makes anything appear at will in a particular stretching.

I would ask you to believe that such an enchantment took place in its time. Baltrusaïtis’s book will tell you of the furious polemics that these practices gave rise to, and which culminated in works of considerable length. The convent of the Minims, now destroyed, which once stood near the rue des Tournelles, carried on the very long wall of one of its galleries, representing, as if by chance, St. John at Pathmos, a picture that had to be looked at through a hole so that its distorting value could be appreciated to its full extent.

Distortion may lend itself — this was not the case for this particular fresco — to all the paranoiac ambiguities, and every possible use has been made of it, from Arcimboldi to Salvador Dalì. I will go so far as to say that this fascination complements what geometrical research into perspective allows to escape from vision.

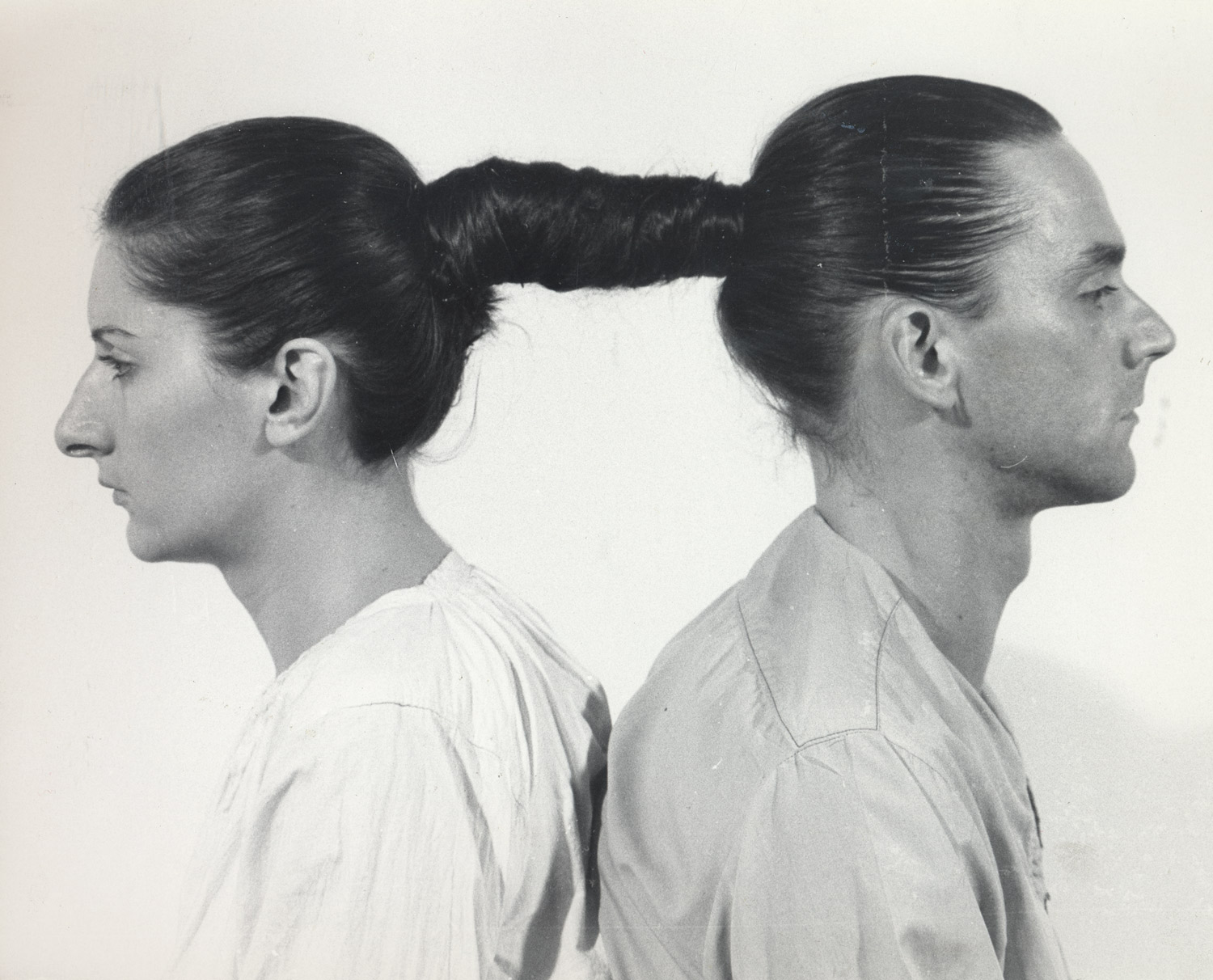

How is it that nobody has ever thought of connecting this with… the effect of an erection? Imagine a tattoo traced on the sexual organ ad hoc in the state of repose and assuming its, if I may say so, developed form in another state.

How can we not see here, immanent in the geometrical dimension — a partial dimension in the field of the gaze, a dimension that has nothing to do with vision as such — something symbolic of the function of the absence, of the appearance of the phallic ghost?

Now, in The Ambassadors — I hope everyone has had time now to look at the reproduction — what do you see? What is this strange, suspended, oblique object in the foreground in front of these two figures?

The two figures are frozen, stiffened in their showy adornments. Between them is a series of objects that represent in the painting of the period the symbols of vanitas. In the same period, Cornelius Agrippa wrote his De Vanitate Scientiarum, aimed as much at the arts as the sciences, and these objects are all symbolic of the sciences and arts as they were grouped at the time in the trivium and quadrivium. What, then, before this display of the domain of appearance in all its most fascinating forms, in this object, which from some angles appears to be flying through the air, at others to be tilted? You cannot know — for you turn away, thus escaping the fascination of the picture.

Begin by walking out of the room in which no doubt it has long held your attention. It is then that, turning round as you leave — as the author of the Anamorphoses describes it — you apprehend in this form… What? A skull.

This is not how it is presented at first — that figure, which the author compares to a cuttlebone and which for me suggests rather the loaf composed of two books which Dalì was once pleased to place on the head of an old woman, chosen deliberately for her wretched, filthy appearance and, indeed, because she seemed to be unaware of the fact, or, again, Dalì’s soft watches, whose meaning is obviously less phallic than that of the object depicted in a flying position in the foreground of this picture.

All this shows that at the very heart of the period in which the subject emerged and geometrical optics was an object of research, Holbein makes visible for us here something that is simply the subject as annihilated in the form that is, strictly speaking, the imaged embodiment of the minus-phi [(- —)] of castration, which for us centers the whole organization of the desires through the framework of the fundamental drives.

But it is further still that we must seek the function of vision. We shall then see emerging on the basis of vision, not the phallic symbol, the anamorphic ghost, but the gaze as such, in its pulsatile, dazzling and spread out function, as it is in this picture.

This picture is simply what any picture is, a trap for the gaze. In any picture, it is precisely in seeking the gaze in each of its points that you will see it disappear.

Questions and Answers

François Wahl: You have explained that the original apprehension of the gaze of others, as described by Sartre, was not the fundamental experience of the gaze. I would like you to explain in greater detail what you already sketched for us, the apprehension of the gaze in the direction of desire.

Jacques Lacan: If one does not stress the dialectic of desire one does not understand why the gaze of others should disorganize the field of perception. It is because the subject in question is not that of the reflexive consciousness, but that of desire. One thinks it is a question of the geometrical eye-point, whereas it is a question of a quite different eye — that which flies in the foreground of The Ambassadors.

FW: But I don’t understand how others will reappear in your discourse…

JL: Look, the main thing is that I don’t come out a cropper!

FW: I would also like to say that, when you speak of the subject and of the real, one is tempted, on first hearing, to consider the terms in themselves. But gradually one realizes that they are to be understood in their relation to one another, and that they have a topological definition — subject and real are to be situated on either side of the split, in the resistance of the phantasy. The real is, in a way, an experience of resistance.

JL: My discourse proceeds in the following way: each term is sustained only in its topological relation with the others, and the subject of the cogito is treated in exactly the same way.

FW: Is topology for you a method of discovery or of exposition?

JL: It is the mapping of the topology proper to our experience as analysts, which may later be taken in a metaphysical perspective. I think Merleau-Ponty was moving in this direction — see the second part of the book, his reference to the Wolf Man and to the finger of a glove.

FW: You have provided us with a typical structure of the gaze, but you have said nothing of the dilation of light.

JL: I said that the gaze was not the eye, except in that flying form in which Holbein has the cheek to show me my own soft watch…Next time I will talk about embodied light.

(26 February 1964)

from Flash Art n°98-99, 1980