Some years ago I ordered a batch of butterfly chrysalis online. They were intended for a project by an artist, who shall not concern us here. While I love the weird things I’ve done and learned through art, on this occasion the experiment turned out rather disturbing. When you order pupae online, you can’t exactly know what stage of development they are in, or how long it will take the butterflies to hatch. You may already guess where the story is going. When the package arrived in the mail, delayed by some days, and I carefully opened it, I found in the patch of cotton bedding creatures in a state of in-between that was both fascinating to the curious mind and deeply saddening at the same time. The dark environment inside the soft packaging, which had travelled across land and water, had apparently caught these insects in a state of half-transformation, half inside their cocoon and half about to leave their temporary casing: some tiny faces, some legs, some partly soft and partly firm bodies, caught in a state of perpetual transformation whose predestination was never to be complete.

I still think about my encounter with these tragic, otherworldly creatures. I feel like I caught a glimpse of a halted process I was never supposed to see. And I feel guilty for having ordered the chrysalis in the first place; my desire to bring them to where I was, for the sake of art, was what sealed their fate. Arresting their development and leaving them to their shady half-lives, these were mutants literally caught in a state of metamorphosis.

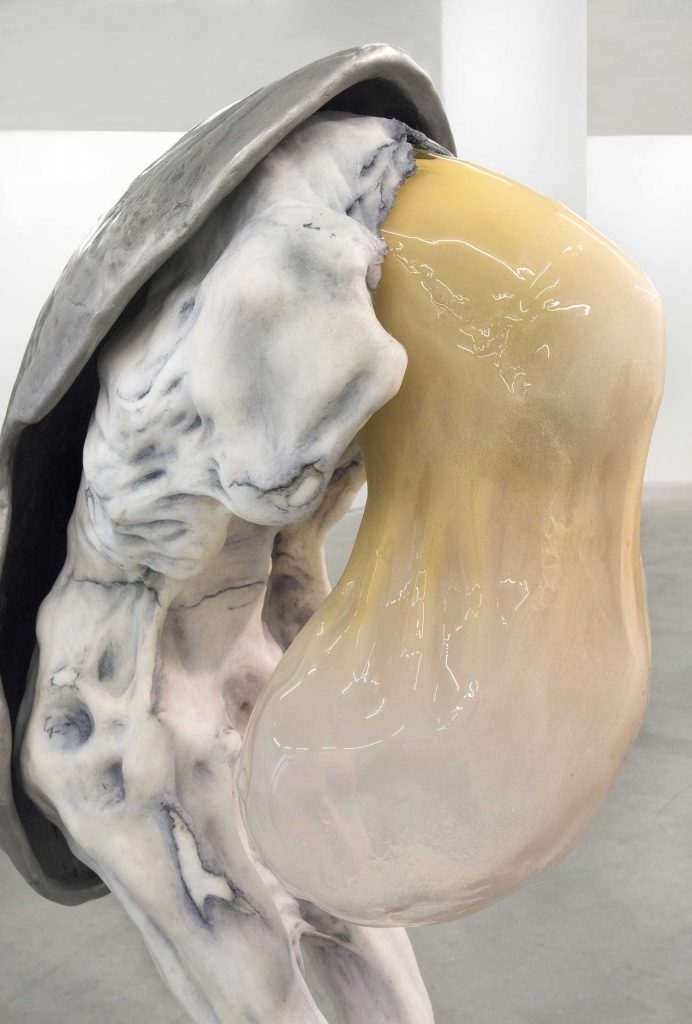

Thinking about Ivana Bašić’s work has allowed me to develop a different perspective on this half-state that has haunted me for years now. While her sculptures are reminiscent of the butterflies’ intermediate condition, theirs is a different destiny than that of my travelling chrysalis. In Bašić’s works, the neither-nor represents a moment of potential freedom, of liberation from a fixed form. The amorphous bodies recurring in her sculptures are fleshlike, as if on the verge of losing their corporal shape. Made from wax, a soft and almost transparent material, their surface is covered in light hues — ranging from rose to gray to white — of carefully applied paint. Oftentimes they have glass elements: for instance, the leg prostheses protruding out of the body of Stay inside or perish (2016). In the sculptural installation Through the hum of black velvet sleep (2017), a glass volume oozes out of a fleshy torso stripped bare to skin that is tautened over bones, a bent rib cage, and thin, long — too long — legs. The glass shape calls to mind lungs and air leaving the body, as the volume was formed with the force of breath. Wax, on the other hand, can revert back to its liquid state, thus pointing to the temporariness and fragility of form.

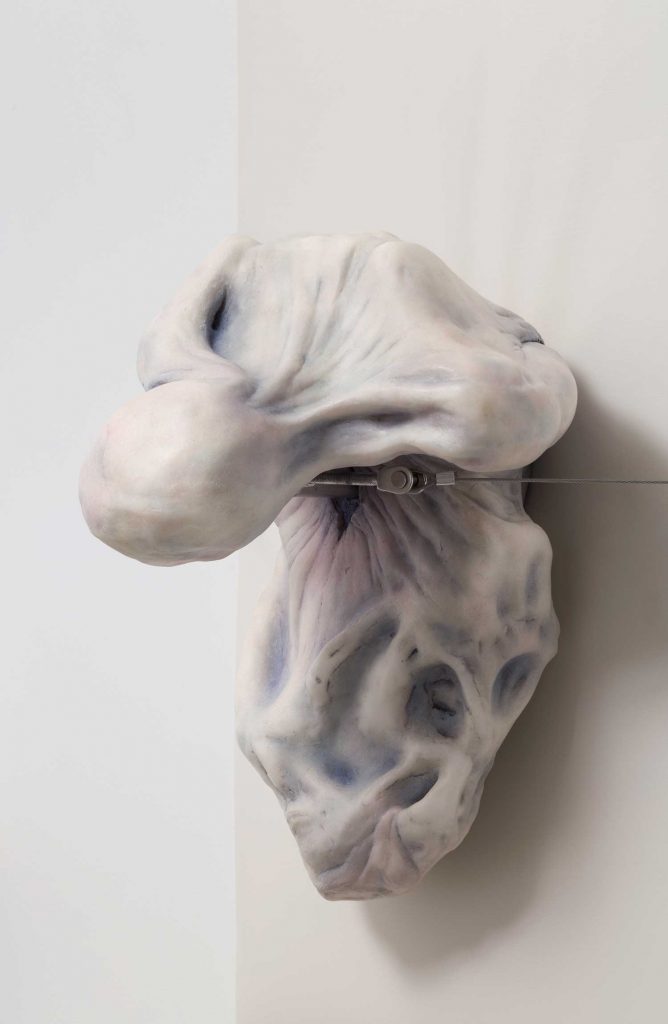

As if testing the sculptures’ will to maintain its form, Bašić often introduces stainless-steel rods that suspend or press them against a wall. They seem to threaten to puncture, or perhaps rather offer to hold in place bodies that are on the verge of losing their integrity. The industrially treated metal rods are unaffected by humidity or other atmospheric conditions, unlike the bodies they’re pushing against. The constellations create tensions and violence reminiscent of that often directed against female bodies and those bodies considered “different” or deviant from the norm.Perpetually on the verge of losing their form, Bašić’s sculptural torsos call to mind philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva’s understanding of the “abject.” Both a feeling and a concept, the abject is a human reaction to the breakdown of meaning, of distinction between subject and object, and of discernment between self and other. Perceived as a threat to one’s very existence, abjection is also linked with the transgressive desire of deviant sexualities, which conservatives condemn for challenging ideas of bodily integrity and purported cleanliness. Film scholar Barbara Creed has shown how the female womb commonly represents the epitome of abjection. The womb blurs the boundaries of inside and outside as it contains a new body that will pass from the interior to the exterior, defying any such clear distinction. In her book The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (2015), Creed shows how the birth process, which includes “blood, afterbirth, feces,” caused the “Church fathers to recoil in horror at the very idea that man should be born of a woman.” Such conceptions have led to numerous exploitative depictions of the womb — and by extension women— as monstrous. This is particularly evident in science-fiction horror films such as Alien (1979), which exploit the horrors associated with the womb that defies boundaries, and the age-old figure of the mother giving birth to another, in this case alien, creature.

Quite the contrary, in Bašić’s sculptures, the threat to bodily integrity and a transcendence of the same is approached from a feminist-fantastical perspective. Set in opposition to a patriarchal society trying to control women’s bodies — see the current backlash against abortion laws in Alabama, Georgia, and other US states — and the brutal policing of nonbinary bodies, Bašić conceives of metamorphosis as a possibility of flight. This flight notably takes the direction toward an inside, when the paths of escape to the outside are blocked. Such fleeing to the inside is not simply escapism. It is an attempt to transform the given self to the point where identification with the nonself is complete, and thus, in the words of art historian Bernard Berenson, a point where “there is no self to die” any longer.

At the moment of writing this text, Bašić is producing a new body of work corresponding to four stages of transformation she has identified as key to achieving such a state of nonself, in the process possibly coming closer to a conceptual notion of immortality. From a first stage of stone and dust as the material “everything” is made of, which binds us to the ground; to a second one in the shape of a chrysalis, in which bodies liquefy with the help of the acid the larvae use for digestion; to a third phase in which a semi-organic, semi-android body emerges, integrating the metal and other inorganic materials it formerly rejected; to a fourth and final moment in which the breath represented by glass vessels is all that remains, leaving the limitations of a material body behind.

Bašić’s latest finalized work, I too had thousands of blinking cilia, while my belly, new and made for the ground was being reborn (2019), is moving in this direction. A chrysalis-like entity made from wax is installed against a wall, held up by two steel rods that seem to bore into its chest. Out of the white, gray, and flesh-colored folds of skin emerges a shiny metal armor, apparently protecting the new body in its fragile state of becoming. From an opening in its back, under the armor, the breath — represented by white or black glass drops in different versions of the sculpture — comes oozing down towards the floor. The drops are elongated as if about to fall, but frozen in their earthbound movement. Similarly, the metamorphosing body from which the secretion emerges is caught in a not-quite-human-nor-fully-insect in-between state.

This transformation from human to insectoid being might call to mind David Cronenberg’s film The Fly (1986). But rather than treading on the well-beaten path of sci-fi morality tales of defeating the monstrous, I’d much rather think of the Russian cosmists’ quest for immortality through metamorphosis. Playwright Aleksandr Sukhovo-Kobylin envisioned the transformation into spirit as the highest goal of human development. As a preliminary step, he thought that human bodies would become ever lighter and smaller, growing bird- or insect-like wings with which they would devise their own means self-propulsion. As George M. Young points out in his book The Russian Cosmists (2012), Sukhovo-Kobylin saw human progress as leading toward the ultimate goal of “freedom from spatial constraint, in other words, its passing into spirit.” If humans were to eventually inhabit and transcend the entire universe, he determined that “we must evolve beyond our present, earthbound state.” Rather than Cronenberg’s fly, who begs his lover to eliminate him in the final scene of the film, in Sukhovo-Kobylin’s cosmism death is defied by the transformation of the mortal flesh into an eternal, immortal substance.

As Bašić’s sculptures pass from humanoid to multiple other states of being, they call to mind what the philosopher Catherine Malabou in her essay “Repetition, Revenge, Plasticity” (2018), in e-flux’s Superhumanity project, has referred to as the posthumanist “idea that the human might contain its own alterity.” In a similar way to how Kristeva conceives of the abject as the breakdown of self and other, this containment of infinite repetitions of another post- or trans-human in the human itself, according to Malabou, represents a “debasement of any ‘proper’ essence of the human.” The psychotic state caused by the breakdown of the human essence might lead us to think of the pathological attraction to the abject “other” body, as experienced by the protagonist of Clarice Lispector’s novel The Passion According to G. H. (1964). In the story, G. H. finds herself in a room pondering humanity. She encounters a cockroach climbing out of her wardrobe and quickly crushes it with the door. In the feverish cascades of Lispector’s writing, the protagonist becomes more and more obsessed with the severed insect’s body halves, from which white matter comes spurting out. She finally decides to lower her own body down to where the roach is lying. As her humanity and personality are breaking down, she inserts the thick drops of excretion into her mouth.

G. H. ruminates that “dying is the greatest risk of all … and with you I shall begin to die until I learn all by myself not to exist, and then I shall let you go.” Ingesting the liquid that comes oozing out of the roach, a creature that has replicated for 320 million years without changing, G. H. encounters her own “debasement of any ‘proper’ essence of the human.” The moment of tasting the cockroach represents the ultimate abject, of foreign liquids entering the body and threatening to undo its integrity. G. H. is aware of the transformation she is undergoing: “The pieces of my rotten mummy clothes falling dry to the floor, I was watching my transformation from chrysalis into moist larva, my wings were slowly shrinking back scorched. And a belly entirely new and made for the ground, a new belly was being reborn.”

Going back to my chrysalis crisis, I return to the horror of the abject and of having caused the disintegration of these fragile bodies, interrupting their metamorphosis, and realizing that they would never become butterflies. Bašić’s sculptures, to the contrary, follow the cosmist conceit that the evolution of humans — and other creatures for that matter — means to move beyond any earthbound material state. Approaching a vanishing point of spacelessness through their four-stage transformation, they bring us closer to a bodiless substance and an ideal spiritual state of being. This metamorphosis toward the nonself may be the path toward immortality. As Berenson’s quote in the beginning of The Passion According to G. H. suggests, “A complete life may be one ending such a full identification with the non-self that there is no self to die.”