It’s easy to feel lost while watching one of Rachel Rose’s videos. Rather than mere confusion, this sense of disorientation is more akin to driving down a rather beautiful and winding road for the first time, not noticing the details that might help you in making the return trip. Rose creates spaces that look so much like our everyday lives, yet have been slightly augmented, perhaps with an unexpected jump cut to seemingly unrelated found footage. Locations and subjects in Rose’s work register at first as familiar, their foreign quality being slowly revealed. Regarding the self-sufficient and self-governing nature of her videos, Rose has said, “I try to construct a work so that it has an autonomous perspective; almost like it’s a body of its own, with its own kaleidoscopic way of seeing.” This dual vision propels a sense of timeliness and otherworldliness within her work — a place to lose yourself when you’d rather be anywhere but here.

In less than three years, Rose has amassed a concise and nuanced body of work — just three videos — that has captivated many with its skillful facture, playful wit and unassuming topicality. Her videos, which generally hover around ten minutes in length, primarily consist of original footage; Rose films with different cameras depending upon the needs of each project. Her imagery and audio is very rarely fed to its viewers “raw” — distortion is one of her primary tools, yet when employed so faintly, so elegantly, distortion is transformed from an act of degradation into one of enhancement. During the editing process, Rose brings in additional found material as needed to complete the picture. Quickly accumulating ideas, visual information, and audio, she views postproduction as a medium unto itself: “I see the edit as a surface through which I can become more conscious of the content.” For this reason, the edit can be seen as the pivotal moment in Rose’s art-making.

“I often feel like I have total amnesia: I can’t remember how I got here or where my body came from or even how this building I’m inside of was built, and when.” Rose’s admission of estrangement from reality is, sadly, universally relatable and a foundational tenet of modernism — the feeling of being lost not only within the constructs of society but also among the layers of cultural sediment deposited by history. This notion of amnesia or trying to regain awareness can be seen as the driving force behind Rose’s works. Desire to understand why things are the way they are propels the artist toward an amusingly diverse assortment of places, events and objects including historical battlegrounds, zoos, modernist architects, EDM concerts and robotics engineering labs.

Each of Rose’s works is conceived during an intensive period of research spent investigating a subject, theory or belief she is intrigued by or perhaps struggling with; those weeks of discovery influence where and what she will film. Rose’s first video, Sitting Feeding Sleeping (2013), centered on her notion of “deathfulness,” the way in which life and the process of dying have been artificially extended in tandem. This line of questioning led Rose to deathful sites including a cryogenic chamber in which a corpse’s blood is continually pumping. Sitting Feeding Sleeping, produced during graduate school when Rose stopped painting and opened her practice to include any medium, is best described as a roving essay. The work employs factual evidence through subtitles and a poetic and theoretical text written by Rose that she reads aloud, her voice stretched and distorted. This isn’t to say that the work is dryly academic; rather, it comes across as a personal endeavor. Moments of intimacy and roughshod experimentation cut through the often slick, well-produced surface of Rose’s high definition footage, providing the viewer a foothold of relatability.

This notion of closeness is heightened in Palisades in Palisades (2014). The video is deeply rooted within its setting, New Jersey’s Palisades Interstate Park, stretching along the Hudson River, both its present-day status (as emblemized by a girl seen sitting in the park on a sunny winter day) and its historical standing as a battleground during the Revolutionary War, where George Washington fled a British invasion. The park was also the site of a recent battle between preservationists and LG Electronics when the corporation attempted to mar the Palisades with a colossal building nearby. Perhaps this struggle between various histories and the present day sparked Rose’s interest in the Palisades — Lauren Cornell once described Rose’s videos as feeling “haunted by history,” though our current-day society seems to have more of a spectral quality in her work.

The video’s opening shot captures a painting of ships in a harbor, which softens in focus and shifts to a clinical close-up of smoothly freckled skin belonging to the previously mentioned jeune fille. Palisades was shot with a Canon C300 — which can zoom in from surprisingly long distances — so that what begins as footage of a girl in a park quickly morphs into a sexless and rather scientific examination of her freckled décolletage against the neckline of her blue sweater, pristine aside from one flake of dandruff. There is a palpable intimacy in Rose’s footage, which seems to dissect everything that it encounters. In another instance, a similar landscape of skin transitions into a close-up of Martha Washington’s arm as depicted in Edward Savage’s eighteenth-century painting The Washington Family. One can feel the desire to reach an almost cellular, interior level within Rose’s work, perhaps revealing physical, cultural and psychological battlegrounds, visible or not.

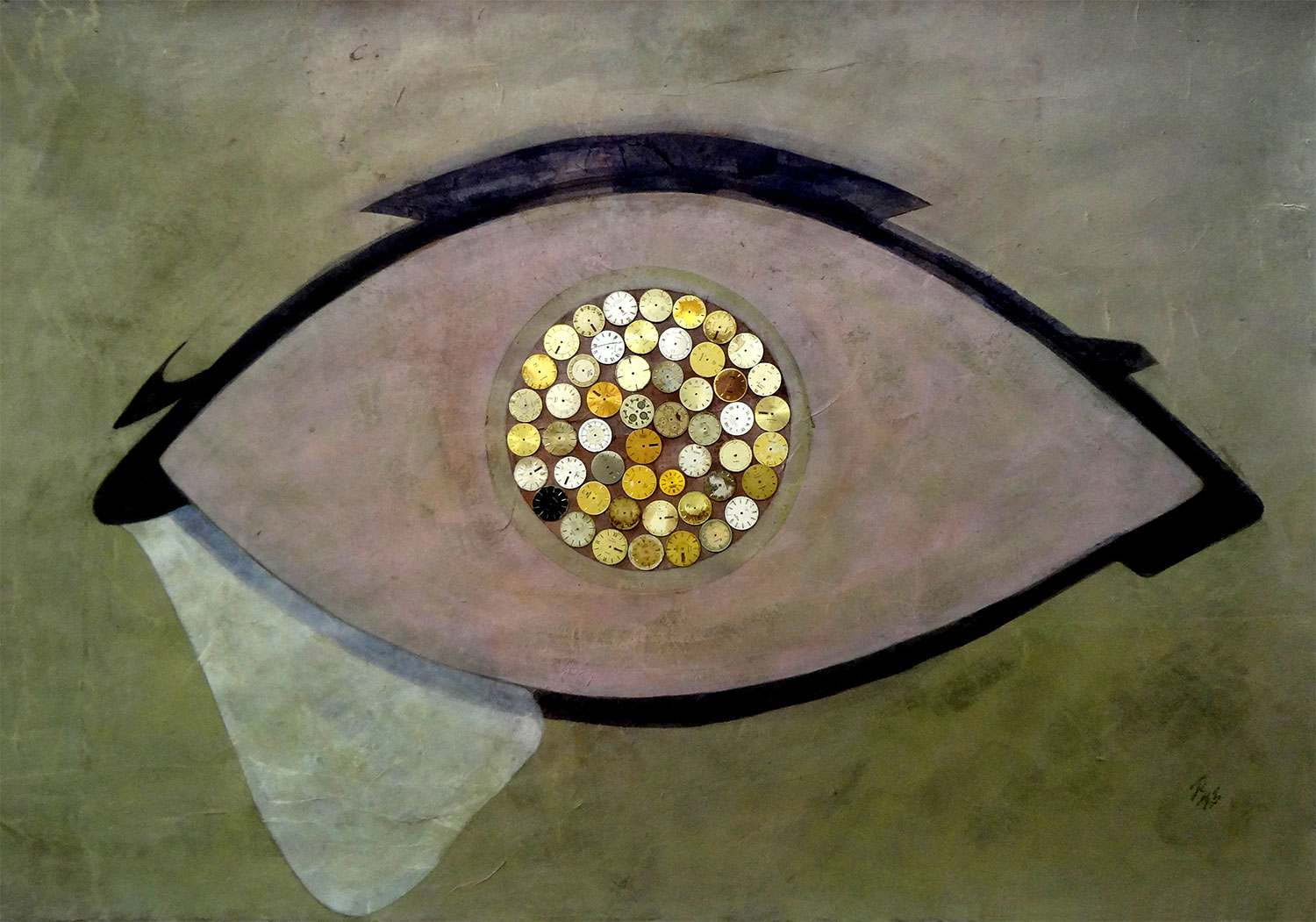

Several writers have compared Rose’s work to painting, a sensible juxtaposition given that Rose was trained in the latter at Yale, studied art history at the Courtauld, and that her videos often include images of paintings as well as rather painterly transitions and edits. Perhaps her best-known work, A Minute Ago (2014), features Nicolas Poussin’s The Burial of Phocion (1648–49), brightly entombed in Philip Johnson’s Glass House, an icon of mid-century architecture. Relationships between the painting and the video can be reached — artificial landscapes, man’s losing battle against nature, rumination upon the dead. Yet, if Rose’s work contains any relationship to the grand tradition of painting, it is one that is forged in the editing process and not necessarily visibly rendered on screen: composition, structure, and layering as underpainting, if you will.

A Minute Ago begins with low-quality footage of a Russian beach, hazy with humidity. A soundtrack of languid strumming on an electric guitar (a live recording of a Pink Floyd song) sets in as the weather suddenly turns and the wind picks up, beachgoers fleeing the shore as inflatable rafts fly away. A downpour of rather sizable hail pelts bystanders panicking for shelter. The apocalyptic footage, found on YouTube, is notable in its cinematography: one long, unbroken, two-minute shot, simply documenting the unpredictable.

A playful Final Cut Pro-esque swipe cut transports the viewer to an impossibly verdant landscape in New Canaan, Connecticut, filmed in shockingly high definition from the interior of the Glass House. For those viewers unfamiliar with the building, the architect himself appears onscreen, back from the grave, to lead a tour. Rose was able to superimpose Johnson’s likeness onto her original footage by rotoscoping Johnson’s movements from an old video, the conditions of which Rose painstakingly matched down to the exact angles and lighting. Fittingly, Johnson’s tour is accompanied by a Steve Reich score (altered by Rose to match the pacing of the video). Both the house and the song are relics from surprisingly outdated notions of (post)modernism. Comically exaggerated footsteps beat against the metronomic soundtrack, further playing into the work’s fine-tuned artifice. Johnson is entirely out of focus in A Minute Ago, which seems appropriate when one considers that the architect, a known Nazi sympathizer, was tied to ideologies that have long been outmoded.

Rose deftly reveals the various levels of artifice found within her subjects in precise moves — after all, the Glass House is regarded by most as a pale imitation of Mies Van Der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. For example, Johnson’s tour is abruptly disrupted by a real recording of police brutality. As the tour continues, Rose’s crystalline footage filmed in situ (using a professional-grade RED camera) starts to glitch. As Rose further distorts her manufactured reality the viewer enters into hostile territory. In this digital melee we hear Johnson’s past coming back to haunt us — an echo of his mention of the central role of the chimney in his house. As the camera moves, the expansive walls of glass begin to shatter into countless pixels, obliterating the screen.

Rose’s forthcoming video, Everything and More, which was nearing completion as this essay went to print, promises to be both her most complex and intuitive work to date. The work is best described as a pseudo-celestial journey through an underwater astronaut training facility, slow-moving globular substances, manga clips, and the lightshows that accompany EDM concerts—all intertwined. The audio contains the sound of waves crashing on a beach, thumping baselines, charged gospel acapella riffs and a brief sampling of a once omnipresent mid-00s pop song. Yet the video’s through-line is an interview Rose conducted with former astronaut David Wolf (conducted after months of attempting to contact him), who has been on four outer space missions. Wolf recounts the details of his return to earth after spending 128 consecutive days in space: “When I first came back to earth… I thought I ruined my life… even my ears felt heavy on my head.” Though almost entirely removed, Rose’s voice perforates Wolf’s monologue (a warm “mhm” here and there), which registers as gentle and reassuring, a conceptual backrub for both Wolf and the viewer, as the work adroitly tiptoes through existentialism.

Since she began exhibiting, Rose’s work has become more cinematic in scope, retaining a level of precision which often belies the homespun aspects of her production — the most stunning instance of which is the foundational support of Everything and More: an amalgam of mysterious liquids, primordial ooze flowing and gurgling in soft tidal ebbs. The magnificently edited layers of liquid pulse and swirl to the beat of the soundtrack, serving as a screen onto which other images are inserted. At one point, Rose’s concoction replicates images of star clusters with ease. To create this effect, household items such as milk, food dye, baby oil, water, soap and olive oil were poured onto a piece of glass, their movements simulated with an air compressor as well as ferrofluid, which allowed Rose to manipulate some of the motion by hand through magnets: “I was trying to see how much I could do with the most basic materials and manipulation of light.” Such material experimentation, which barely registers upon the first viewing, aligns Rose’s practice with those of equally intrepid artists of her generation including Sam Lewitt, Ajay Kurian and Marina Pinsky.

David Wolf’s description of free-floating in space, being able to only see the Milky Way (“…it looked like the universe”) and absolutely nothing else underscores the notion of pure isolation and its opposite — everything and more — which runs throughout the video. At one point in the astronaut’s monologue, filled with hard breaths and fuzzy transmission, he discusses the intensity of returning to earth due to the heightening of his senses by the sterile solitude of life in space. One can’t help but have an empathic response, imaging the complete removal of every person that’s ever bothered you, the absence of scents that clog your consciousness with forgotten memories, and forgetting just how your two legs propelled you along city streets. Everything and More, rife with familiar audio and relatable imagery, muses upon the costs of isolation. In constructing a place where she is free to tease, control and spotlight the societal conventions that surround us, Rose holds up a mirror to our daily lives cluttered with artifice. When you become lost, it’s easier to find your way when you remember just how simply and quickly the glass walls in that glass house shattered.