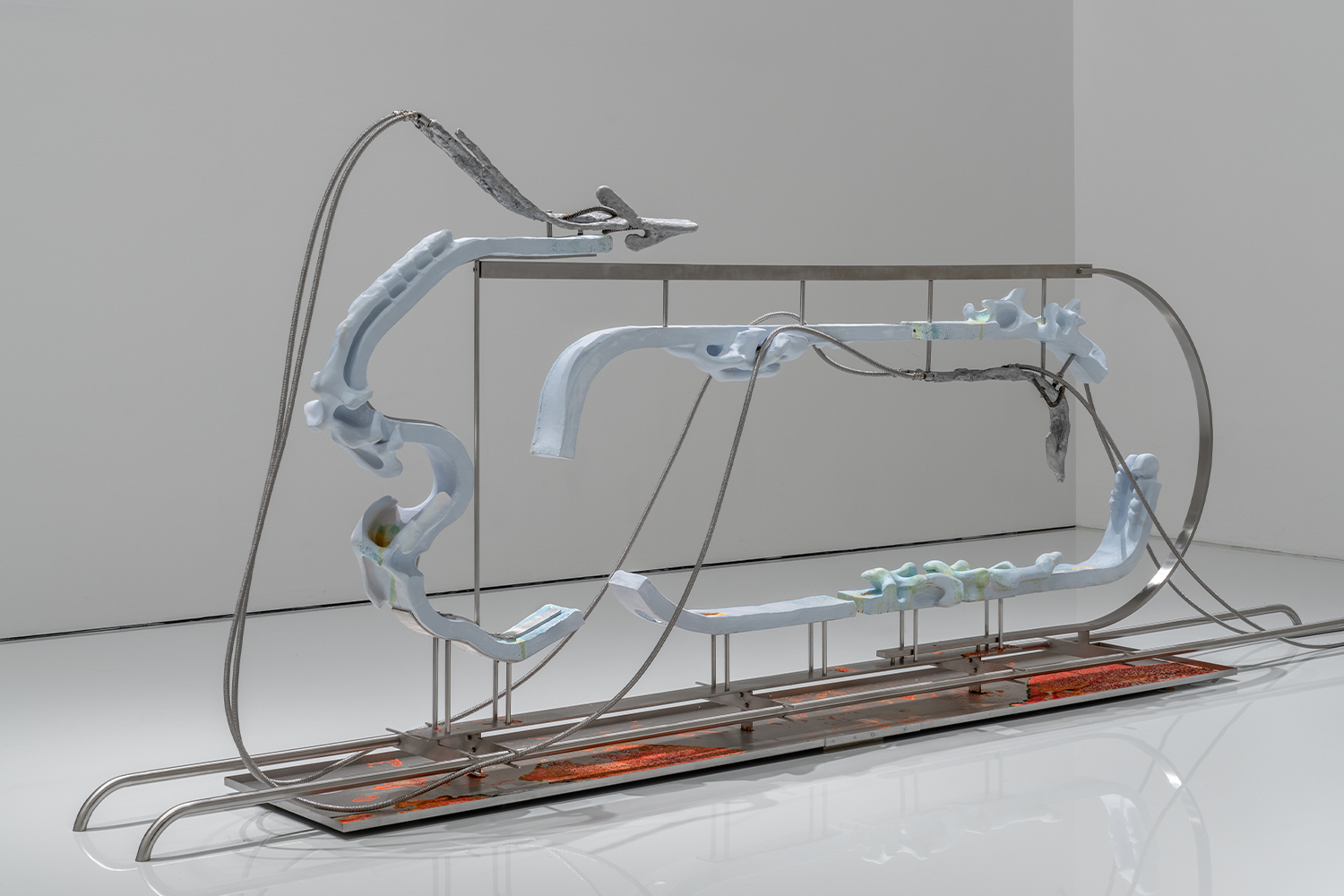

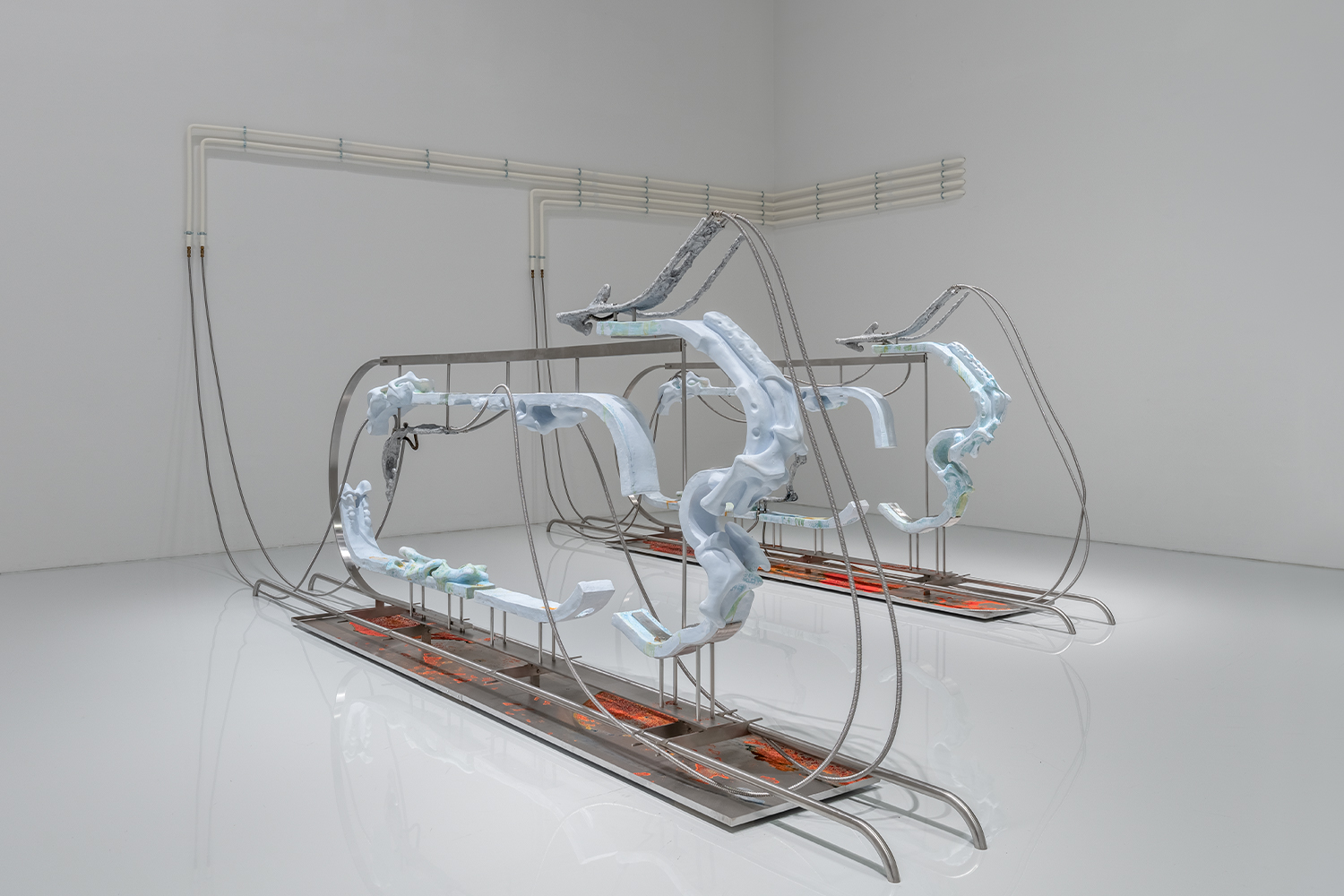

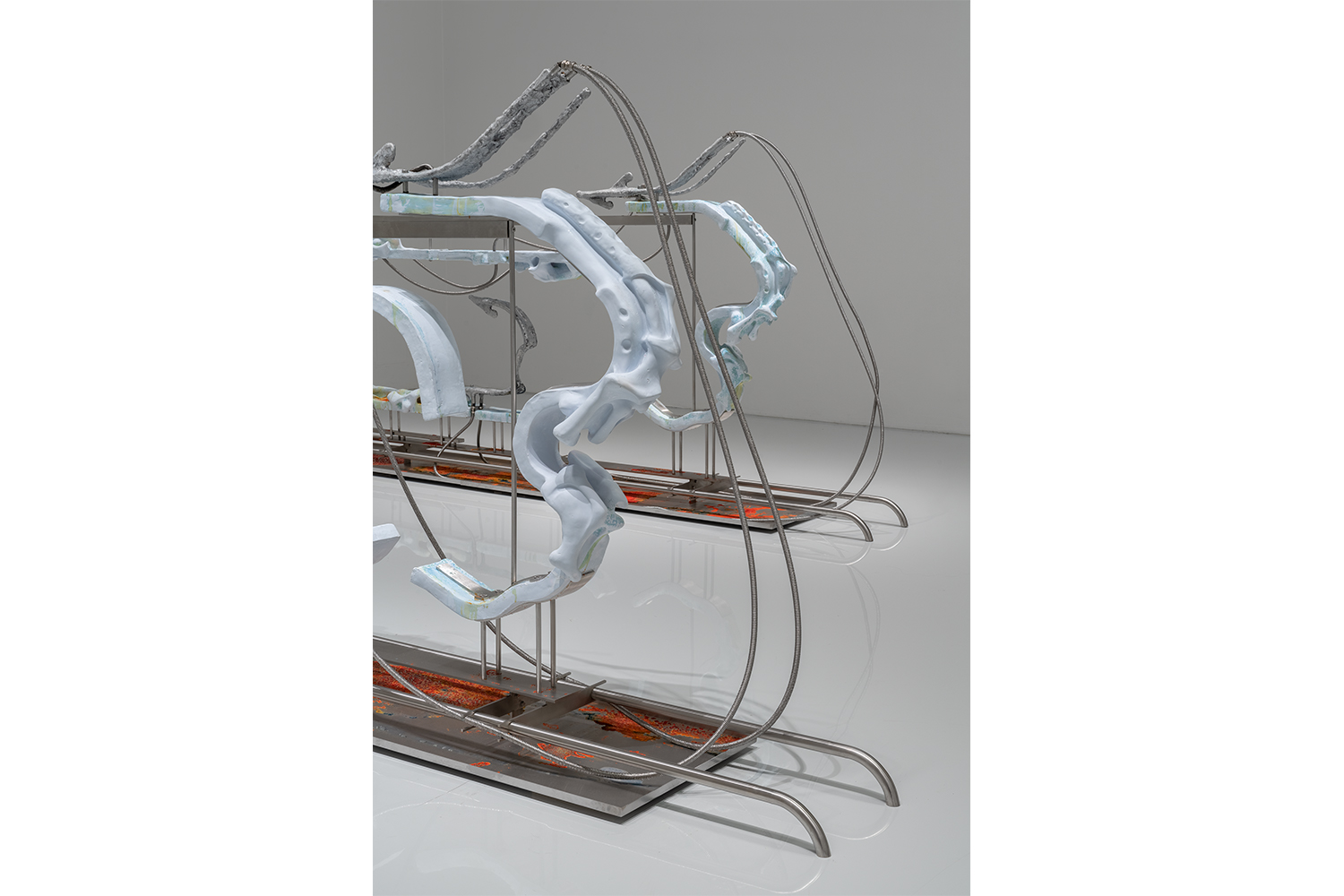

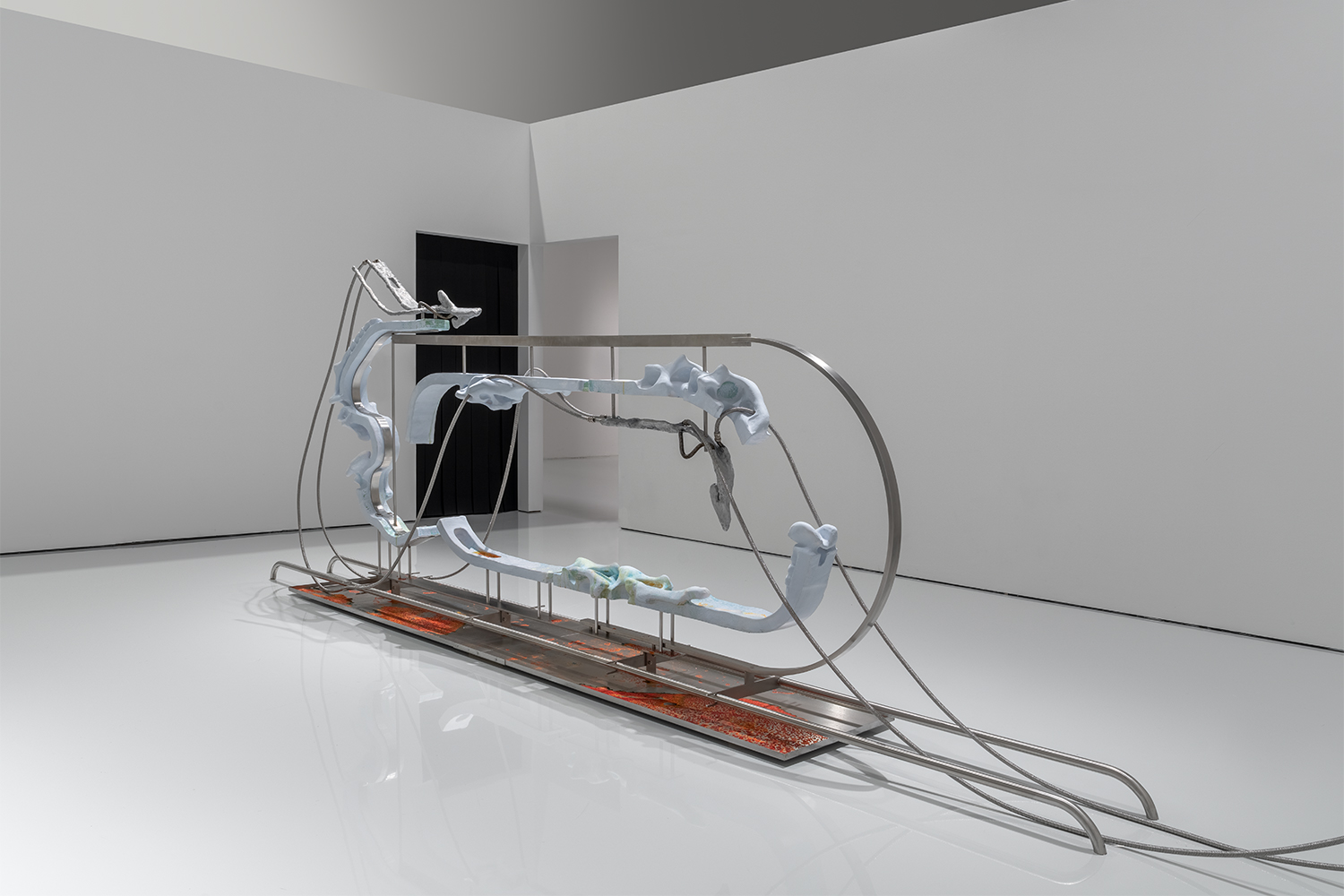

Seeping, oozing, metastasizing, Isabelle Andriessen’s bodily sculptures sit in an affective space between categories. They demand to be read through a combination of materials that resists stasis, as troubled and sticky agents in their own right. Ongoing processes of calcification and condensation measure out timespans that exceed the human, spinning a narrative that will continue long after their time of exhibition. Approaching them in a gallery space provokes an uncanny sense of both the familiar and the simultaneously illegible; perhaps they are future archives for a culture that has toxified its earth and water; or are they beings parasitically feeding off the exhibition architecture? Andriessen’s research and practice builds speculative worlds in which she explores the agency of clusters of interlacing materials, parsing queer materialism and probing plastics, crystals, and coolant for latent dark intent.

Natasha Hoare: I’m interested in your approach to world-building through materials that aren’t often seen in combination.

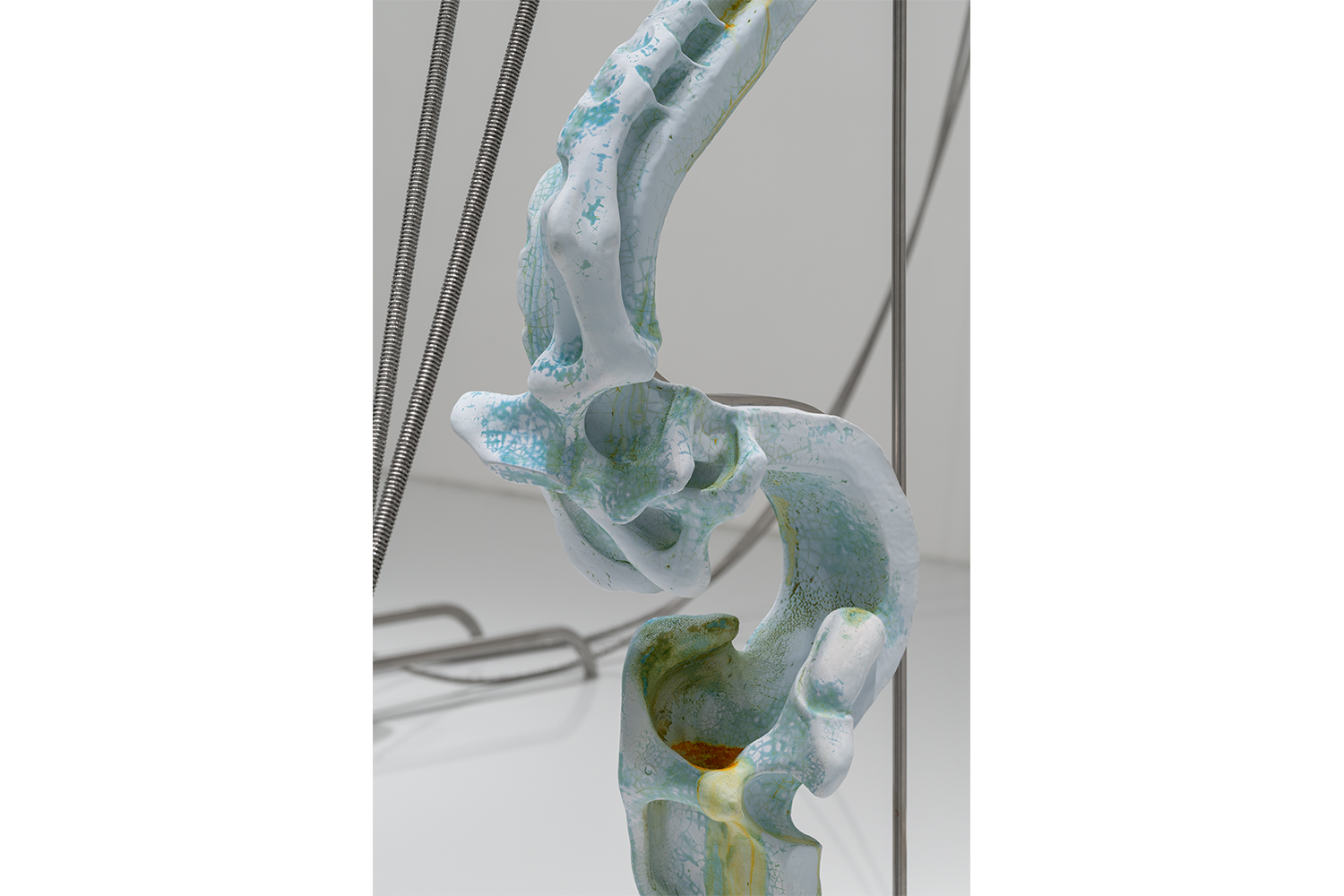

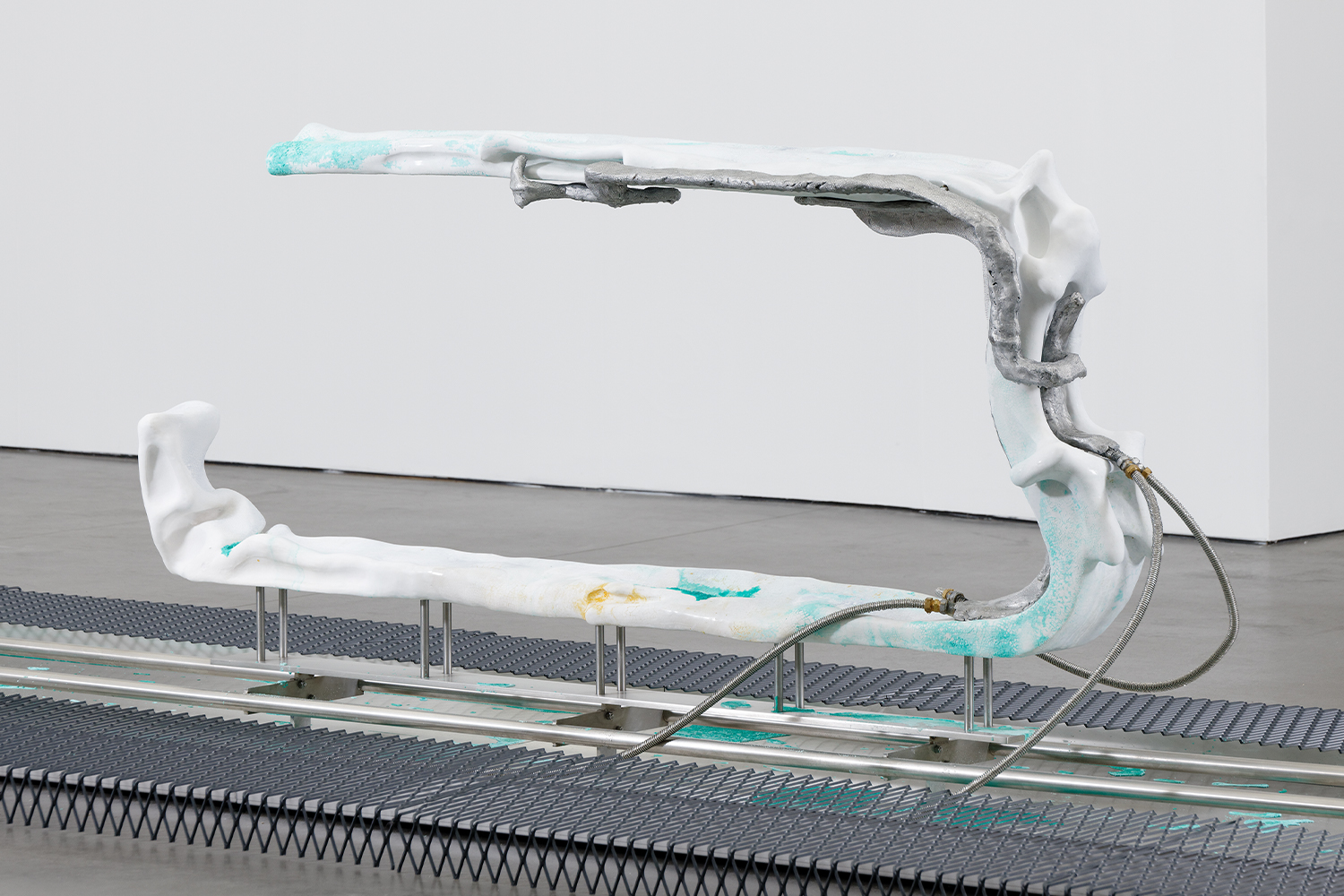

Isabelle Andriessen: My work seeks to create (science) fictional windows into other or alternative realities. I aim to reveal the agency of materials and the passage of time. By animating inanimate materials I want to reveal the unreliable characteristics within materials that might otherwise seem dormant or passive. In order to uncover a darker agenda, I manipulate synthetic materials so that they creep and crawl, move and drip, leak and ooze, as if they obtain a metabolism that is infected. They are composite entities that you don’t expect to move; they’re static and were made to be resilient. I started working with electricity and chemistry as tools, to see how I can develop a range of materials that gradually change over time. Somehow these sculptures become performers that reveal something of themselves that wouldn’t be clear or visible in one visit, but only over multiple visits or multiple exhibitions. There is an inherent tension between these events or changes and the fact that they cannot be wholly witnessed; the viewer will always miss a large part of the transformation.

For a while now I have been researching the liminal space between performance and sculpture while questioning notions of conservation. What if sculptural changes over time are irreversible? How does this affect conservation and restoration? When my works are acquired, they come with a set of instructions, or activation manual, like a performance. Performance within the art institute primarily centers around the human body performing, but I’m interested in expanding that definition and creating a relationship in which my artworks somehow interact with the art institute.

NH: The works demand a revised sense of institutional care and attention, and they also evade classification, which is the methodology of the museum catalogue. There are lots of problematic practices that have been embedded in cataloguing artworks. I’m thinking of this poem called “Voyage of the Sable Venus,” in which poet Robin Coste Lewis traces catalogue entries of historical artworks that depict Black bodies — and their use of racist language. Your work starts to approach these issues from a different angle, but also suggests that the museum is not a neutral terrain, that it plays a role in determining materiality as inert and passive. Your recent sculptures trail pipes in an arterial lattice that penetrates the walls of the exhibition space. It’s ambiguous as to whether they’re sucking them dry or if it’s a symbiotic, or perhaps parasitical, relationship.

IA: Absolutely. I create a sub-architecture within the architecture. My works derive from imaginary landscapes; ruins within an architectural system. I’m interested in this disruptive relationship that you’re pointing out. I want to address other worlds or alternative realities where different rules apply, where these things somehow start to move and feed off each other. I definitely research and play with these notions of the host and the parasite; I am interested in a codependency of different entities that control one another or feed off one another. These sculptures are seemingly tapping into the museum’s infrastructure and climate control systems, but they’re also responding physically to the atmosphere. The aluminum pieces contract moisture from the air, whereas the crystallization of the ceramics responds to the moisture secreted from inside these pieces. Within that interaction there is total unpredictability. I want to create from within that tension my agency as the artist and that of the materials. Their behavior can only partly be predicted — they go beyond my or the museum’s control. I want to facilitate the agency of these materials so that they can act like a choreographed orchestra across the track or the chorus of the exhibition.

NH: The event of condensation is interesting when considering the position of the viewer in your work. I had an initial sense that the sculptures don’t need a human witness. I wondered if that was related to you making a bleak prognosis for mankind? They provoke a very strong sense in me that the time of their unfolding is on a different register to my own sense of time; that they will exist after my death. They’ll continue secreting and calcifying. I was wondering if they’re really for a future cyborg viewer, who will understand them through a different set of semiotics. But the presence of the condensation is interesting, because the viewer’s own breath is going be part of the humidity of the museum space and will condense on the sculpture. That opens a door for the presence of the viewer. I suppose this shifting sense of the viewer is one of the inherent ambiguities in the work. The sculptures effect a shuttling between positions.

IA: I thought a lot about the viewer as a witness of an accident, or a relic with some sort of supernatural power — perhaps like Saint Januarius, whose dried blood, in rare moments of public display, liquifies. I like the sense of wanting to witness an event like that. There’s something unique and uncanny about witnessing an inanimate object transition from one state into another, or to obtain fluidity or motion. Some of these works will still be in a process of crystallization even if they are in storage or in a collection. I’m interested in the capacity of these works to continue their agency even if they’re outside of the viewer’s ability to witness them. I want to expand the limitations of conservation and to research what it means for an artwork that is still changing when it’s in storage. Part of the progress or the narrative is lost.

NH: You will never again have the previous version.

IA: Exactly, it is irreversible. I want to embed a notion of urgency and charge in them somehow. The sculptures I developed in 2018 look significantly different today. Maybe they were more beautiful then, or more pristine, and have become a bit dirty, greasy, or disgusting. I can never reverse it, and that’s intrinsically a consequence of showing and viewing the work. With the performance or “activation” of the work, something automatically gets lost as well.

NH: You used the word “disgust” then, and I had a question around the relationship you have to science fiction and horror, a blend of the two that relates quite closely to H. R. Giger and Cronenberg. Particularly to the tradition of abjection as figured by Julia Kristeva, whose theorization links horror to the maternal body and procreation. These leakages and seepages are seminal and self-reproducing. Your sculptures don’t need a mother. Perhaps they are hosts rather than mothers themselves?

IA: I don’t mean for the works to address a subconscious, yet within my practice I intend to channel queerness embedded in materials — from an active act of switching between familiar and unfamiliar and finding comfort in something being both attractive and disgusting. I aim to channel entities that are weird, fluid, or uncanny and to address a world attuned to death, thriving with new organs and sex, allowing for new entanglements.

NH: The figure of the monster seems apposite. The monstrous resists categorization; it’s liminal, we can’t place it. Your sculptures occupy a position between animate and inanimate, toxicity and naturally occurring processes. Are they from the future but somehow relics or future fossils. There’s a temporal and formal in-betweenness that speaks to the category of the monster.

IA: Absolutely, and I think notions of queer materiality are important, as defined for example by Mel Y. Chen. I want to point to entities that seem to have no place in economics, mathematics, or earth systems, while yet — perhaps under the surface — they do. They are in and of themselves, and of their own logic. I’m more interested in these plural entities — and creating space for plural beings to thrive. Within this practice, addressing modes of survivalism and activism is really important to me. We live in a time in which the Earth’s system is highly disrupted. Biotic and abiotic components are fusing due to the contaminating and toxic materials we spill into our environment, like oil, plastics, hormones, and chemicals — forcing more and more life forms to endure and adapt to extreme violent pressures. Entities that have different abilities to thrive and persist. They are resilient to toxic and violent environments. This again all comes together in an imaginary world in which I’m trying to give them a voice.

NH: Do you have an apocalyptic imagination?

IA: Yes, maybe. Though I don’t think I relate to the religious origin of the word “apocalypse,” which comes from this moment where God or a higher force decides it’s the end of humanity. I resonate more with the notion of an endless continuum of events. I believe there is apocalypse upon apocalypse, or catastrophe upon catastrophe — an inhospitable darkness that is also a fertile source for new flourishing entanglements.