In my early twenties I worked as a gallery attendant at Dia:Beacon, where I was tasked with maintaining the precise level of directness permitted in phenomenological encounters between visitors and the Minimalist sculptures on view. A gallerygoer grazing their hand against a plywood box or leaning against a massive hunk of corrugated steel enjoyed too much immediacy, so I would whisper, “Please, don’t touch the art!” while speed- walking toward them, walkie-talkie flapping at my side. The experience of a tourist snapping a selfie in reflective glass shards scattered on the floor was surely much too mediated, so I admonished such offenders: “No pictures! No phones!” Minimalist sculpture aims for a direct but distant relation between an observing body and a taciturn object in real time and physical space. The institution supplied the “real time and physical space.” My job was to maintain it.

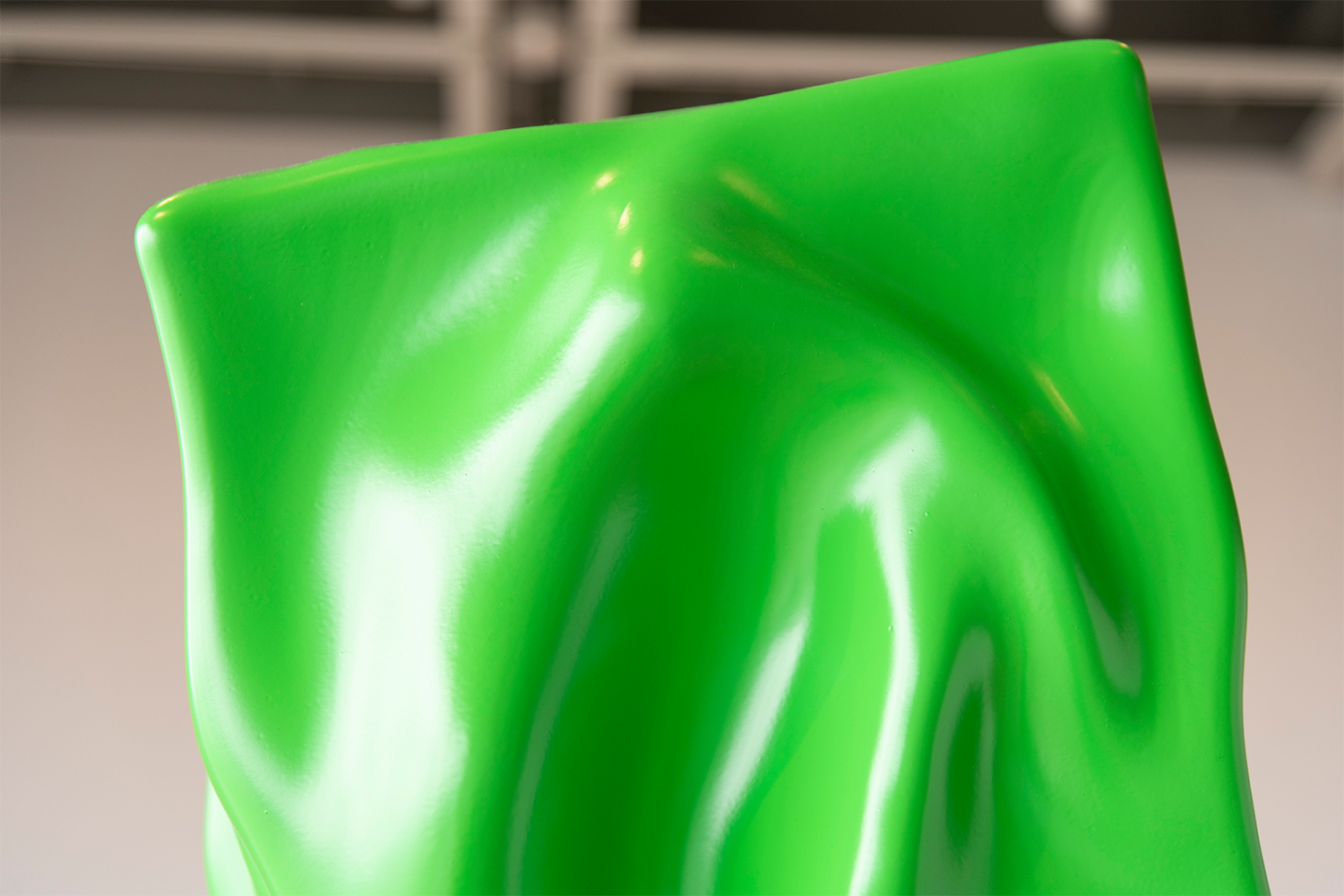

It’s been more than a decade since I left my job at Dia:Beacon; the iPhone has cycled through nine upgrades, and even the art world’s strictest phenomenological purists have relaxed their digital photography policies. When I visited the most recent Whitney Biennial, no one stopped me from snapping a photo of Aria Dean’s Little Island/Gut Punch (2022), a chroma-key-green plinth that has never known “real time or space.” Dean created the object by running a digital model of a monolith through a collision simulation and 3-D printing the impact as a sculptural form. It’s a verb from Richard Serra’s list, digitally done unto a series of ones and zeroes: the effects of “to crash” appear without ever having occurred outside the machine. And, unlike Minimalist objects that hedge their bets on the presence of an observing subject, Little Island/Gut Punch couldn’t have cared less about me. Instead, it called out to interface with my smartphone, its green-screen color inviting further edits and iterations. Though this object doesn’t necessarily believe in a direct encounter, it wants to be messed with, nonetheless.

Dean has described Little Island/Gut Punch as “a big green monolith being hit by an invisible force.”1 It’s impossible to tell whether this force strikes the plinth from the outside or whether the form is crumpling onto itself from some internally felt pain: Its assailant, after all, does not properly appear. What kind of force is this? What violence cannot be located in time and space but has observable effects? A literal read might identify the force as the artist who staged the collision, though she worked upon a digital model and not the sculpture itself. Perhaps the force can be found in the 3-D printer responsible for Little Island/Gut Punch’s materialization. But, in rendering destruction, a 3-D printer does not, itself, destroy. The force that suspends Little Island/Gut Punch in its crumpled state cannot be represented. It is, in a word, suprasensuous: what Marx might have called a “real abstraction,” one of those metaphysical niceties productive of, and seeking embodiment within, physical reality; or what Frank Wilderson might identify as the machinations of a political ontology that has secured anti-Blackness across the longue durée. In any case, when made to register the effects of something beyond “real time and physical space,” the Minimalist object suffers a great blow.

A similarly invisible force with highly visible effects wreaks havoc in Dean’s play Production for a Circle, which was most recently staged at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in 2019. Over the course of a half hour, four unnamed characters (referred to only as A, B, C, and D) are not so much voided of idiosyncrasies, interiority, and individuality as they are revealed to themselves as having already been voids. Like Minimalist sculptures, the only specificity accorded to A, B, C, and D is that of their structural formation (as white, Western, bourgeois subjects) and their encounter with each other in time and space. These are people as plywood boxes: well-formed and meticulously maintained, nice to look at and think about, resoundingly hollow, and relatively useless outside their display.

In the first few minutes of the play, A (Bingham Bryant) grows impatient with B (Annie Hamilton) for feigning surprise at the death of an artist named Sam, about which, apparently, both A and B already knew. He confronts her; she defends herself: “What do you mean? I was acting surprised because you acted surprised! … You have to follow suit!” A goes on to tell B that the dead artist Sam had a daughter, also named Sam, who married a man named Sam and gave birth to sons, all Sams. With this tidbit (now genuinely surprising to B), B’s initial feigned surprise — her studied calibration of facial expression and vocal inflection to match that of her interlocutor — becomes emblematic of a certain practice of bourgeois social propriety, according to which the incestuous repetition of the same, of Sam, is made possible by dipping into a readily available repertoire of assumable gestures, tones of voice, and styles of comportment. A, B, C, and D attempt to perform both individuality and connection through displays of aesthetic preference: When D remarks upon the fish A prepared for dinner, the two realize with delight that they frequent the same farmers’ market fishmonger; when C and D arrive, they’re eager to narrativize their subway ride for their friends in near unison, but find they disagree as to whether or not a public make-out sesh between two women had invaded their fellow commuters’ personal space. Meaning and identity cohere around such shared judgments and minor squabbles, and objects (whether commodities, narratives, or other people) serve as sites for the foursome’s formation as such.

The thing is, though, that A, B, C, and D can’t find their objects, or else can’t distinguish themselves from them. The production is minimal and the stage sparsely set: This is theater in the round. When A gets up to use the bathroom (and, in the process, loses track of his face), there is no backstage to which he can disappear, no architectural frame behind which he can excuse himself from the representation. Both players and audience are bereft of an object to judge: B and C exclaim over an absent fish, and A attempts to entertain with a story but can’t find a narrative to follow. Perhaps there never was any “there” there: no deep kernel of meaning to be excavated and expressed by A, B, C, and D. Though none dare propose this outright, the four grow increasingly frantic as they find themselves repeating each other’s sentences and confusing each other’s experiences. The same organizing force that shores up white, Western, bourgeois subjectivity (“You buy fish from that guy?! I buy fish from him, too!”) also tears it apart: coincidences are revealed not as serendipitous similarities but as the effects of a political ontology that forms bodies into subjects and sorts these according to race, gender, age, class, and so on.

Once their deindividuation has progressed such that no “I’s” remain at the helm of these bodies, the very hollow sameness and voiding of meaning that appeared trivial at the play’s outset now portends, if not a radical politic, at least a bit of raucous excess. Production of a Circle ends with A, B, C, and D repeating “same,” “same,” “same” to each other. Now, though, the word does not function as a vehicle for empathy (“I feel the exact same way!”), nor does it point to the literal sameness of the Sams, the repetition of whose name allowed the continuity of lineage and property across bodies and time. Production of a Circle’s closing sameness is the sort achieved when one applies the Photoshop blur tool to an image one time too many: a sameness that marks the outer edges of representation.

Dean has referred to Production of a Circle as a means of “taking these proper Western subjects and … smearing them across the stage.”2 As a conceptual function, smearing aims neither to obliterate the existing order such that a Fanonian tabula rasa might emerge, nor to repeat what is with an iterative twist. Smearing maintains what it intervenes in, but disorders it such that any expressive content or recognizable signifiers are rendered noncommunicative. A representational graphite drawing smeared becomes a monochrome abstraction; a subjectivity smeared is made generic. And, though philosophers from Bataille to Foucault and artists from Duchamp to Bernadette Corporation have variously theorized the end of Man and made attempts to get rid of themselves, Dean’s practice proposes that the most effective theorists and practitioners of deindividuation have always been those barred from constituting and representing themselves as individual subjects. Much as accelerationists failed to see Black (non)subjects as the already inhuman agents capable of revving up the revolutionary machine,3 anti-humanists failed to see that the deindividuation they so desired is already being lived and thought by those rendered, to borrow Orlando Patterson’s term, “socially dead” by Western civil society.

It is perhaps for this reason that, in King of the Loop (2020), Dean figures death not as an end to life but as a state of being without subjectivity — and, correspondingly, without stable narrative emplotment in real time and physical space. At once solo performance, architectural structure, and multi-channel video installation, King of the Loop tells the not-quite story of a man who crashes his car in a Mississippi river and wanders to a nearby abandoned plantation, where several squatters tell him of a man named Brah Dead who lives in a shack on the property. Edem Dela-Seshie, the sole performer in King of the Loop, creeps and saunters about an enclosed mirrored structure outfitted with multiple surveillance cameras, reciting a text that seems as if cobbled together from a film screenplay, seventeenth-century epic, and bargoer’s ramblings. Dela-Seshie both is and is not this text’s narrator: he frequently pulls the performance score from his pocket to recall a line or punctuates a phrase with an illustrative gesture (a kick for “the boot,” shadowboxing for “enemies”). Such significatory overloading unhinges language from speaker and, as Dela-Seshie’s reflection multiplies and the video cuts between cameras that Dela-Seshie occasionally addresses as “you,” the authorial locus of the text disintegrates into an anonymous, looping murmur of images, reflections, myths, citations, and clichés.

When the narrator or protagonist (for, though the two are not entirely distinguishable, neither do they fully cohere) enters Brah Dead’s shack, he finds only mirrors: first-person subject and third-person image, performance and performed, collapse, and the narrator/protagonist realizes that he is Brah Dead, having forgotten his (non)identity in the crash. Dela-Seshie plays the narrator/protagonist’s discovery of his own deadness as no big deal. Unlike A, B, C, and D, Brah Dead doesn’t much mind having lost — or having never had — an individual, recognizable subject position. No matter: he continues to prowl and glide about his mirrored shack, reciting lines that do not originate from a stable interiority into his home’s many cameras and for his many reflections. If Brah Dead could speak across Dean’s oeuvre to A, B, C, and D in his characteristically repetitive manner, he might say something like, “There, there; there’s no ‘there’ there.” The era of representation might be ending. You might not get to be a subject anymore, and that might be okay.