I’m a little lost without you / That could be an understatement / Now I hope that I have paid the cost / To let a day go on by and not call on you – Arthur Russell, “A Little Lost,” 1994

I’m in a restaurant called KTown Pho in downtown Los Angeles, nibbling on milk buns and Yan Wo, an acerbic bird-saliva drink known as an aphrodisiac. Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of sexual love, swiftly regurgitates the white swallow-hatchling foam down my throat, like an impatient mother with better places to be. I’ve often swallowed lustful white foam in bitterness, so my empathy levels are high. Empathy levels are less lofty for the lunatic sitting across from me at table four with unconstrained serial-killer vibes, hyper-focused, chowing down on Phở chiên phồng, which is often made with dog. (I lived near Hanoi, so I would know. I found this out the hard way.) He’s reading Rape of the Sabine Women with a faded Rubens painting on the cover and has red peat on his work boots, which is entirely unnerving. I leave a few hair strands and lateral incisors on the floor, just in case. Latin mythology is taken very seriously, I’ve found.

Who speaks through Venus and Mars, Aphrodite’s horny spume, Leda and the Swan, the rapes of the Sabines, Arthur Jafa’s daughters of the dusk, and Arthur Russell’s existential confusion? Isabelle Albuquerque, the Los Angeles– based artist with her language of political refusal and aesthetic ignition against structural myths. But she’s speaking in tongues, in the language(s) of the demigods, compiling an assiduous yet casual catalogue raisonné of sculpture and performance, asking us to reimagine singularity. Singularity, which is countable and reliable, finds its existential assurance in an invented cipher taken at face value, consumed as erudition, and a theoretical case of didacticism that she is very much against. Isabelle Albuquerque is our schizoid plaintiff splitting imagination.

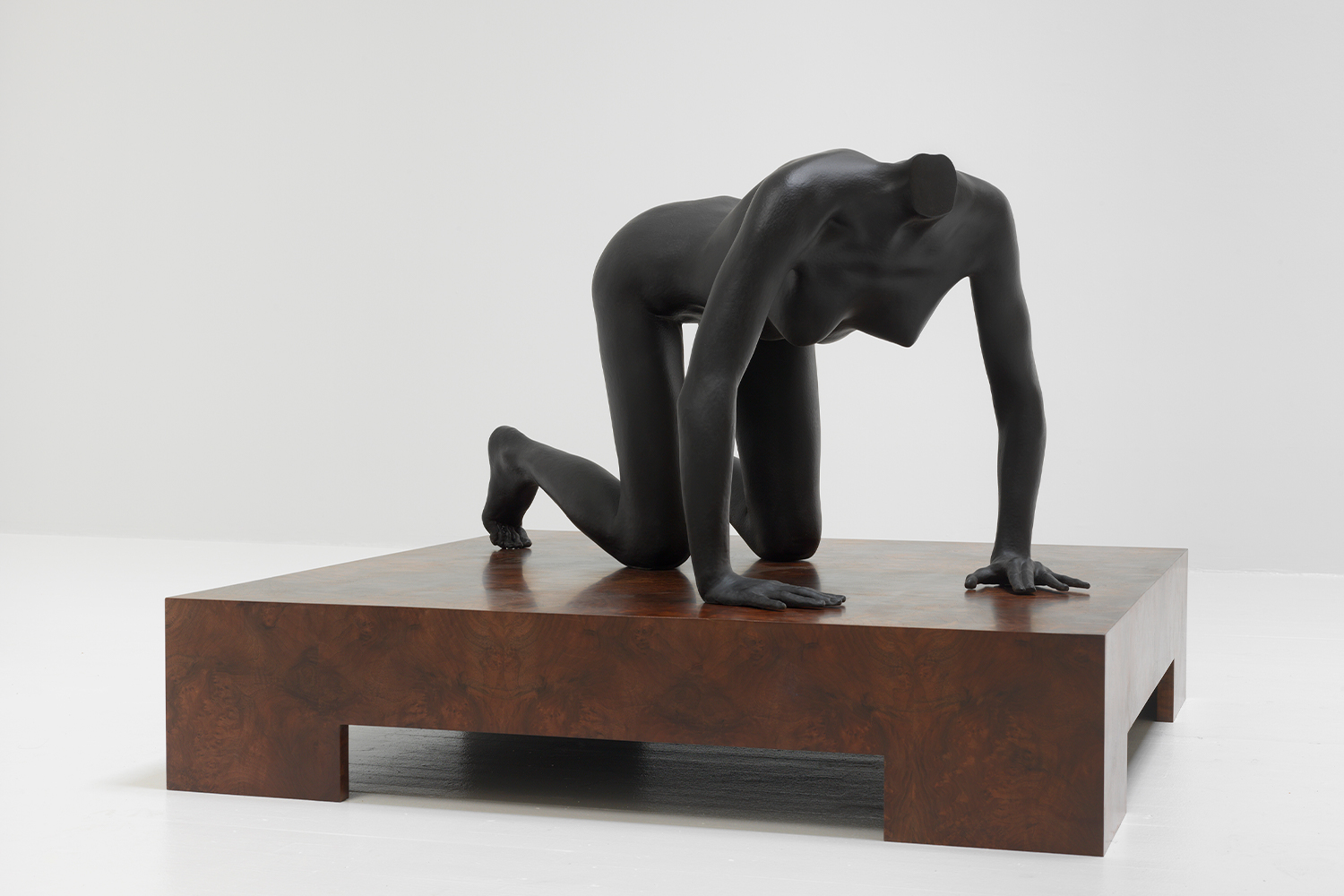

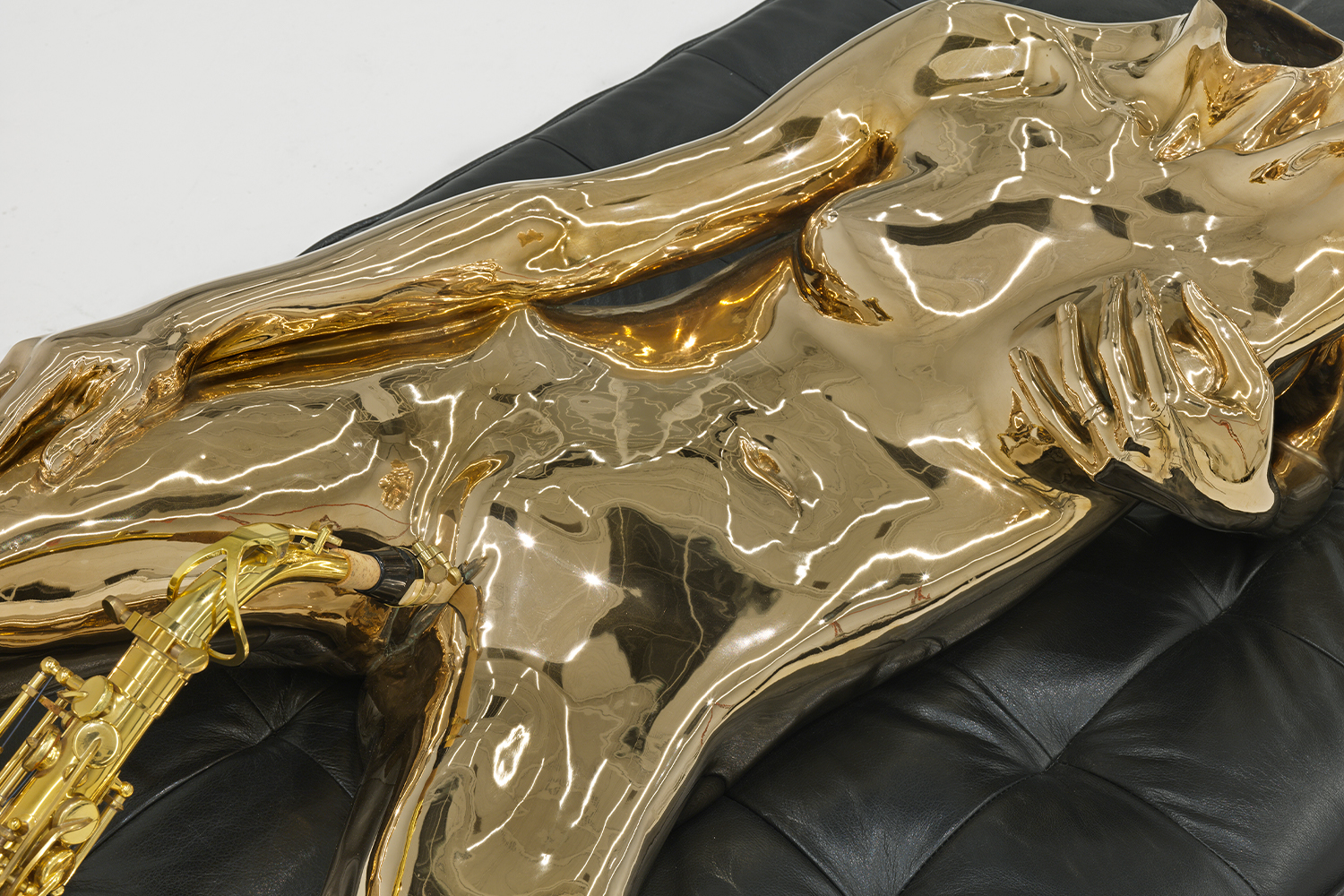

For her solo show “Sextet” at Nicodim Gallery, Los Angeles, in 2020, she culled work from “Orgy for Ten People in One Body” (2019–20). Six sculptural iterations of her own life-size form, scanned in 3D, each cast in different materials: flocked resin, mica-laced Lexus auto-body paint, Gaboon ebony, walnut, and bronze. Bodies sans head — which is quietly surprising since tet sounds like tête, meaning “head” in French. And “head” in English means something else entirely, hmm. (Latin classes in LA are reasonably forgiving.) Plural human forms birthed from one flesh with their calm, leisurely, even decadent studies of mythologies, aloof bodily attenuations, music scores, elegiacal postures, and sex. Always sex. In 1 (2019), Albuquerque casts herself as Leda in an adaption of the “seduction” (rape) of Leda by the Greek god Zeus in William Butler Yeats’s poem “Leda and the Swan” (1923). But this time, an enduring bronze vulva commands the licks of a golden saxophone, taking over the poem’s savage through line and creating her own overpowering song; she blesses us by laying suave blue goose eggs instead of the traditional gold. The pulsating mess of male pathogens and victimhood morphs into a pulsating pussy perfectly ruptured. An artist entirely in command of her version(s) of a narrative. It’s hard to overlook the faint Electra complex that sings a subtle, witty refrain from the sculpture; her father was a saxophone-playing scientist, after all. As a loose Brechtian aside, Zeus also dipped his toes in Oedipal-esque endeavors with his eau-de-Nil agrarian sister Demeter, who sprang the egg for Dionysus, if I remember correctly. There are all kinds of orgasmic rites and fetal thyroid-hormone deficiencies to be harvested in these narratives that make breaking the fourth wall utterly forgivable. Low-key hubris, high in humor and libidinal energy, she powerfully asserts the female gaze, multiplying the myth of Leda like the loaves and fishes, homiletic offerings holding us hostage to nothing at all. 4 (2020) brands itself sexually vocal with a black rubber figure on all fours in sensual Dionysian principles, a wet, doggy-style recipe that does want to be eaten. A talismanic flower sprouts from an athletic figure well versed in the Lamaze method, figuratively speaking, fingers stained with black stamen, semen, and orgiastic qualities. Orgies in and of themselves are a manifestation of plurality, scores of lovers, S & M apparatuses, multiple desires, demands, orifices, ejaculate, and, malheureusement, personalities (ugh). Looking into the teethy abyss of desirous possibilities, complainant Albuquerque makes a precise argument for cock(y) takeovers that fills in several feminist narratives simultaneously, uncapped and unplugged. And anyway, who doesn’t love edibles and a wet slap on the arse.

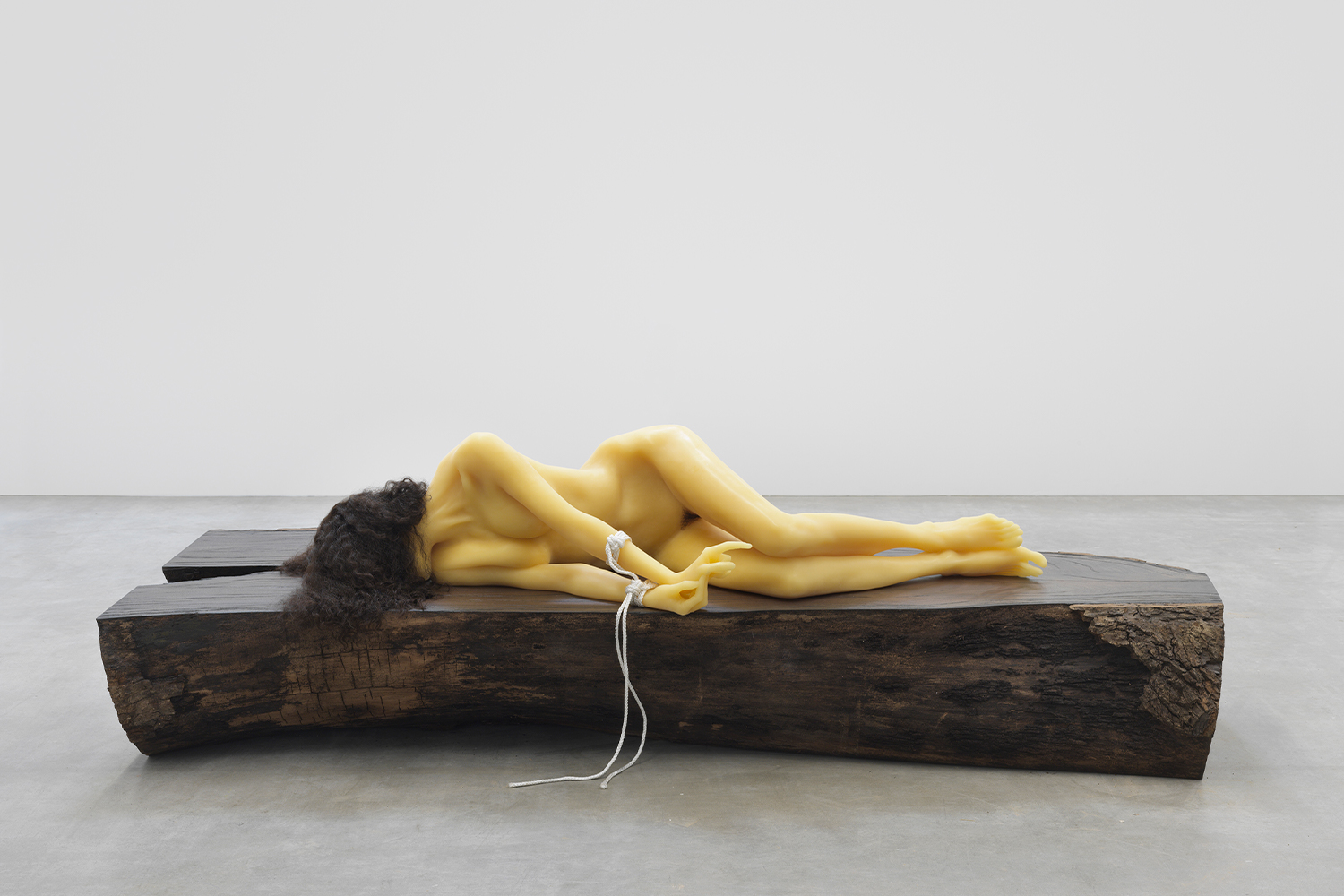

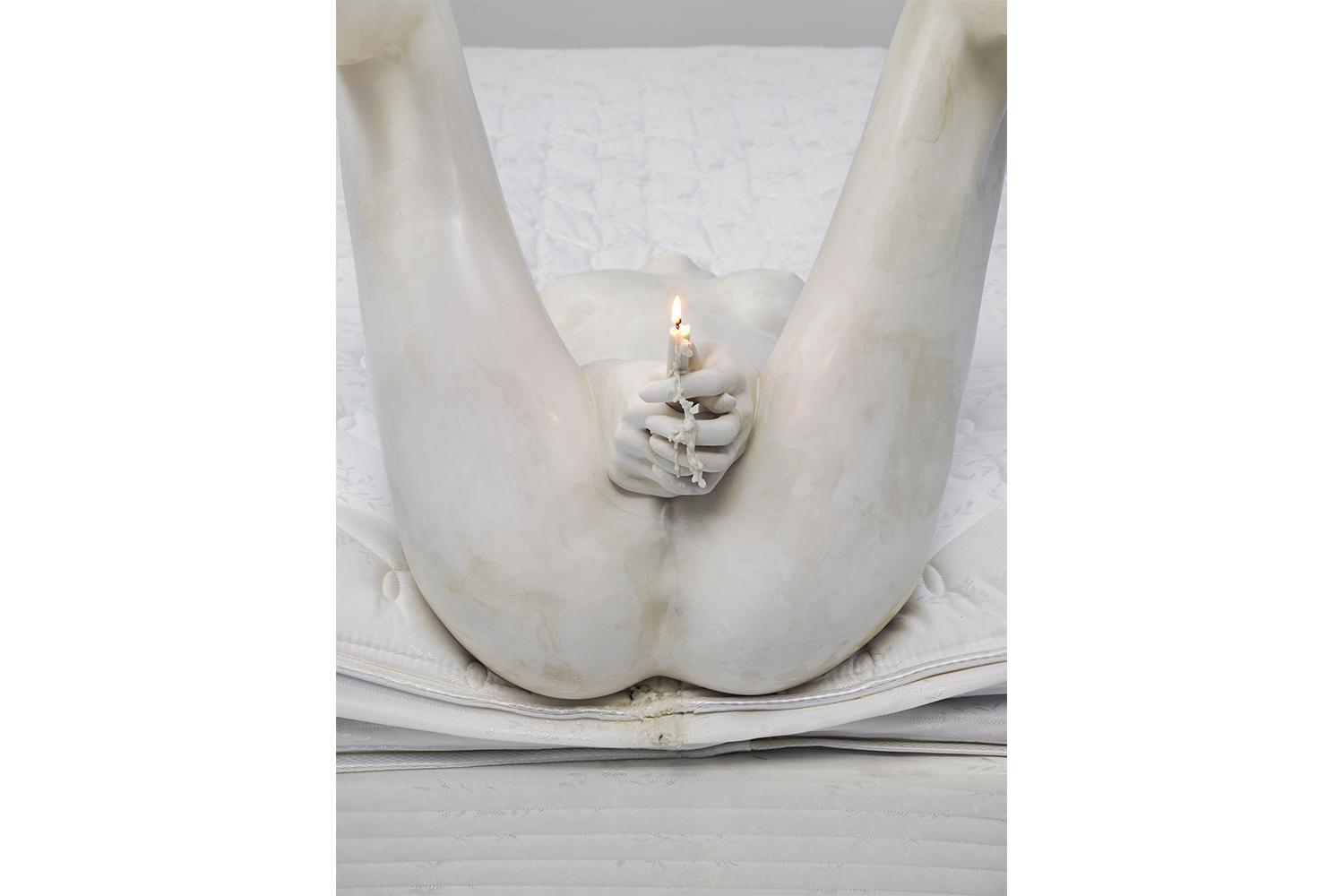

Pieces from the series have been shown in Nicodim’s group exhibitions “When You Waked Up the Buffalo” (2020), “Skin Stealers” (2019), and “Hollywood Babylon: A Re-Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome” (at the Former Spago Restaurant on Sunset presented in collaboration with Jeffrey Deitch and Autre Magazine in 2020), among others. One sculpture from “Orgy for Ten People in One Body,” 5 (2020), depicts a woodland creature with queen-composure, a seductive Bambi-woman wrapped in deerskin, taxidermy capsized, with ebony hooves for feet, flown in from the tropics. The mythical fawn-sapien wears a traditional gold wedding ring, which explains why she’s cut her head off. In a pious vigil of preparation, Albuquerque ate venison, among other exacting delectables, for three weeks while the work was being created, which proves, beyond a reasonable doubt, that we know who killed Bambi’s mother. She’s got game — pun very much intended. Against the smoky whiff of venison, we see a madcap methodological process arise, honoring Stanislavsky in brusque genuflection. (Konstantin Stanislavski was the granddaddy of method acting, which Isabelle takes quite seriously, apparently.) His punishing theatrical dictums permeated her modus operandi through the making of sculpture 5: living feral, grazing on wheatgrass and elderberry (she’s LA-based, so not a stretch), half-animal, half-person, an alien metamorphosis that cannot be contained. Sultry and doe-eyed, the final work powerfully reimagines the erotic songs of Solomon from a rabid, acephalic body, hot, bothered, and parched with carnal desires. Beheading the patriarchy is thirsty work. She’s intrusive, no doubt about it. Penetrating deeper into her multifaceted demolition of the patriarchy and its hold on women’s bodies (1st Julian calendar AD–present day), Albuquerque pays artistic dividends to the women of Imperial China’s Sui Dynasty (581–618) with her alabaster sculpture Double Olisho (2020). Dildo for two, a sex mission from an ancient world with a punishing division of the sexes: men plow, women weave, yadda yadda. Double Olisho flips the power, the déjà déjà vu, pursuing anointed milky discharge as women plow, instead, into one another, with twelve colossal inches of Sapphic yearning (six inches apiece, so clearly not life-size so far as I’m aware). Not that I’ve adequately researched, but I’m certain the preservation of Yang essence was a man’s idea.

In former lives as a dancer, performer, and musician (in her music and performance duo Hecuba with Jon Beasley — and, by the way, Hecuba was a Greek goddess during the Trojan War, which is pertinent — she also functioned as a kind of amanuensis for her mother, her Other, the great feminist artist Lita Albuquerque, whose environmental installations and site-specific works made their mark on the Californian desert and grand dunes south of Giza. Her critically acclaimed installation Sol Star (1996) represented the United States of America at the 6th International Cairo Biennale (1996): ninety-nine blue pigment circles stained the sand, reflecting the stars directly above them and the radius of these heavenly bodies; an artist devoted to multiples, deep self- reflection, and collective identities. Palm trees and botanical fruits aside, it’s perhaps this blue period that influenced Isabelle’s pursuit of a different kind of heavenly body, multiplicities, and creating mythological works that breed celestial narratives, politics, and identities into a billion starry-eyed renditions. And it’s here that the performative finds its purest form. In her latest show, “Orgy For Ten People In One Body” at Jeffrey Deitch, New York (2022–23), the artist continues working like a Trojan, lowering the moat on mirage and infiltrating the gallery with all ten figurative sculptures instead of just six. Albuquerque’s self- reflections are growing, doubling their radius, creating herself again and again, different perspectives untangling the illusion that there’s but one story of self that can sustain us. A Homeric odyssey, a war she’s very much winning. Decollate iterations persevere with erudite departures that are pleasant and unpleasant both, losing her grip on knowing herself (ves) and losing orientation as consolidation fails her. Haloes of saintliness cannot float above guillotined heads, at least not saintliness as it’s understood traditionally. The prickly turbulence of taking up space with incongruities and self-indulgence is purposeful, mind you. And she revels in it.

Her Spotify playlist loops back to Arthur Russell, eyes in brine, with his cello strings made of sheep guts:

I’m a little lost without you

That could be an understatement

Now I hope that I have paid the cost

To let a day go on by and not call on you

Lyrics, a melodic hymnal, spoken to herself, about herself, searching for former (intentionally) lost selves, future lost selves, simultaneous personas, flagrantly disobeying singularity and its costly ambivalence. She’s willing to pay the price, determined for martyrdom, to operate artistically without calling on the same impotent narratives. She, too, has guts. And besides, under what circumstances are our selves true? Holding on to her daydream of debunking myths, Albuquerque, our saint in sneakers, unveiled sculpture 9 (2020) for “Orgy”: a decapitated bronze witch riding an obtusely angled broomstick, Earth meridians upended, gorgeous labia folds devouring the broom, making the very best of the situation. (The real reason little girls love pony rides, I’ll have you know.) Historically, as is known, witches were immolated and burned alive; witch hunting (also known as women hunting) is yet another lamentable mythological narrative Saint Albuquerque is hellbent on transforming.

Isabelle Albuquerque stirs up a new, unholy denomination of piousness in her Salem-style crucible, sins and herbs floating down the Jordan alongside Tituba and Mary Magdalene, brewing molten potions that burn power at the stake, crucify the patriarchy, and all the stories we could do better. Bypassing the myth of devotion to one narrative of self, politics, methodology, medium, desire, and even species, she mutates into a gladiator of plurality, erasing the exquisitely maintained voice of singularity to make way for more. Singularity, they think, is everywhere. But this, says Saint Albuquerque, is a massive misunderstanding.