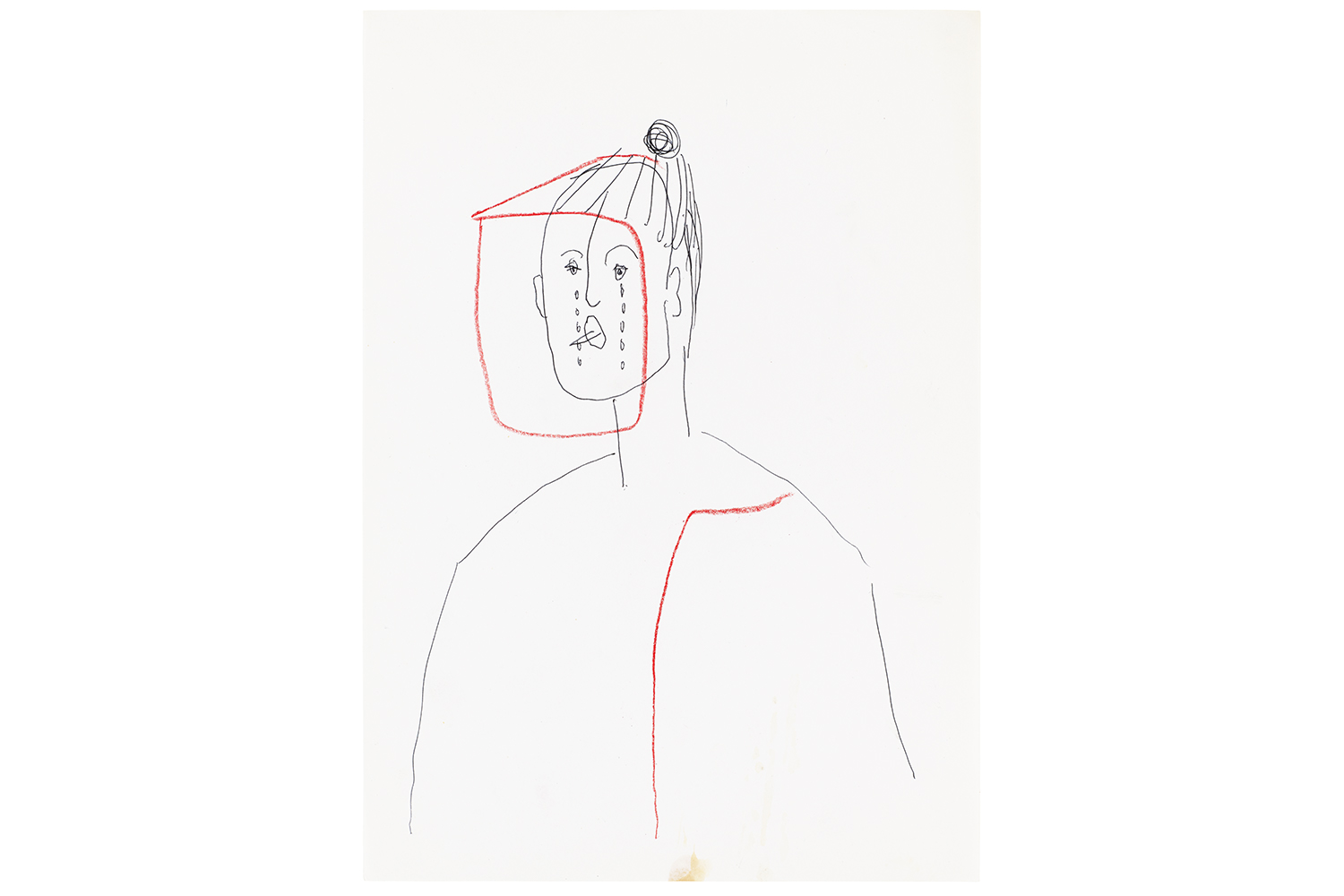

Although a single word could never encapsulate the boundless range of Isa Genzken’s artistic production, one that comes close is “unpredictable.” Since the 1970s, Genzken’s work has incorporated, combined, and juxtaposed mediums including sculpture, photography, painting, drawing, and film, often to create large-scale installations that are as mesmerizing as they are puzzling. The way Genzken chooses to unite the varied elements that comprise her works is characterized by a sense of play, keeping viewers on their toes and evading formulaic traps and expectations. The results leave audiences with more questions than answers and unsettle with their lack of fixity, neat presentation of meaning, or clear significance. It is, perhaps, the ambiguity of Genzken’s work and her inability to be categorically and stylistically pinned down that has led to her varied reception.

Genzken’s recognition in the United States has taken time, with the artist’s first comprehensive American retrospective inaugurated at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2013. Many of the works included in the exhibition had never been seen in the United States before. However, she has long been considered a star in the European, and, especially, German, art world, receiving solo exhibitions in her home country as early as 1976. Regardless of the consistent diversity of her formal decisions over time, Genzken’s practice has always been rooted in sculpture. And, for this, she was a trailblazer.

In the mid-1970s, sculpture was still a largely under-engaged medium in Germany, and women sculptors were nowhere to be found.1 The American art scene, on the other hand, was rife with Minimalist sculpture at the time. Amid this landscape, Genzken not only bridged the gaps caused by the seismic division between the artistic trends in these Western worlds, but also filled them by forging a path toward a new artistic niche in Germany, garnering her a serious and respected reputation among a boy’s club of male greats, including such renowned artists as Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Richter. From 1973 to 1977, Genzken would study under the tutelage of both at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, an art academy famed for its impressive roster of faculty and students, all of whom were at the forefront of cutting-edge artmaking. It was at the Kunstakademie that Genzken’s sculptural sensibility was developed and honed. This quality is the thread that connects the entirety of Genzken’s diverse and wide-ranging oeuvre.

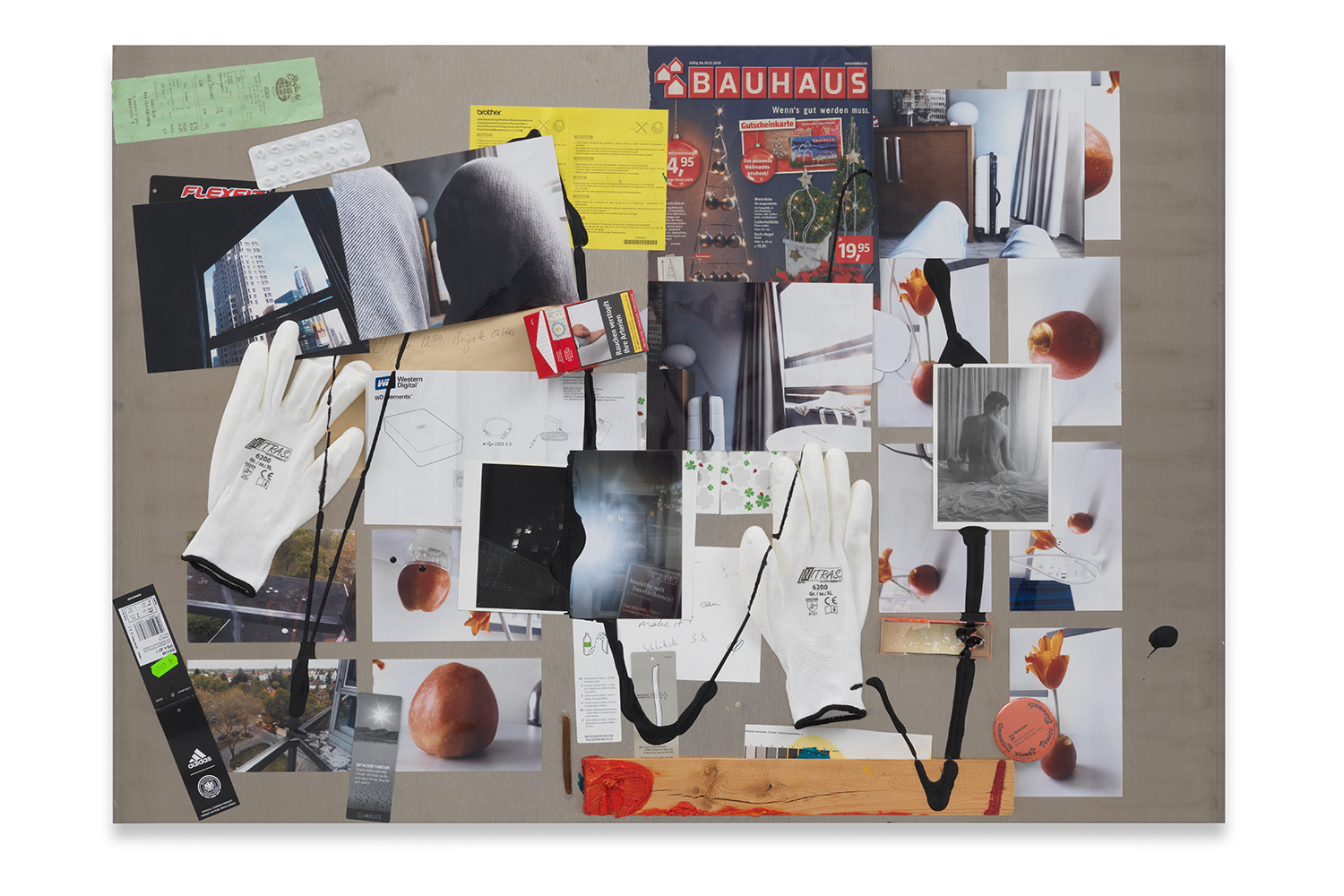

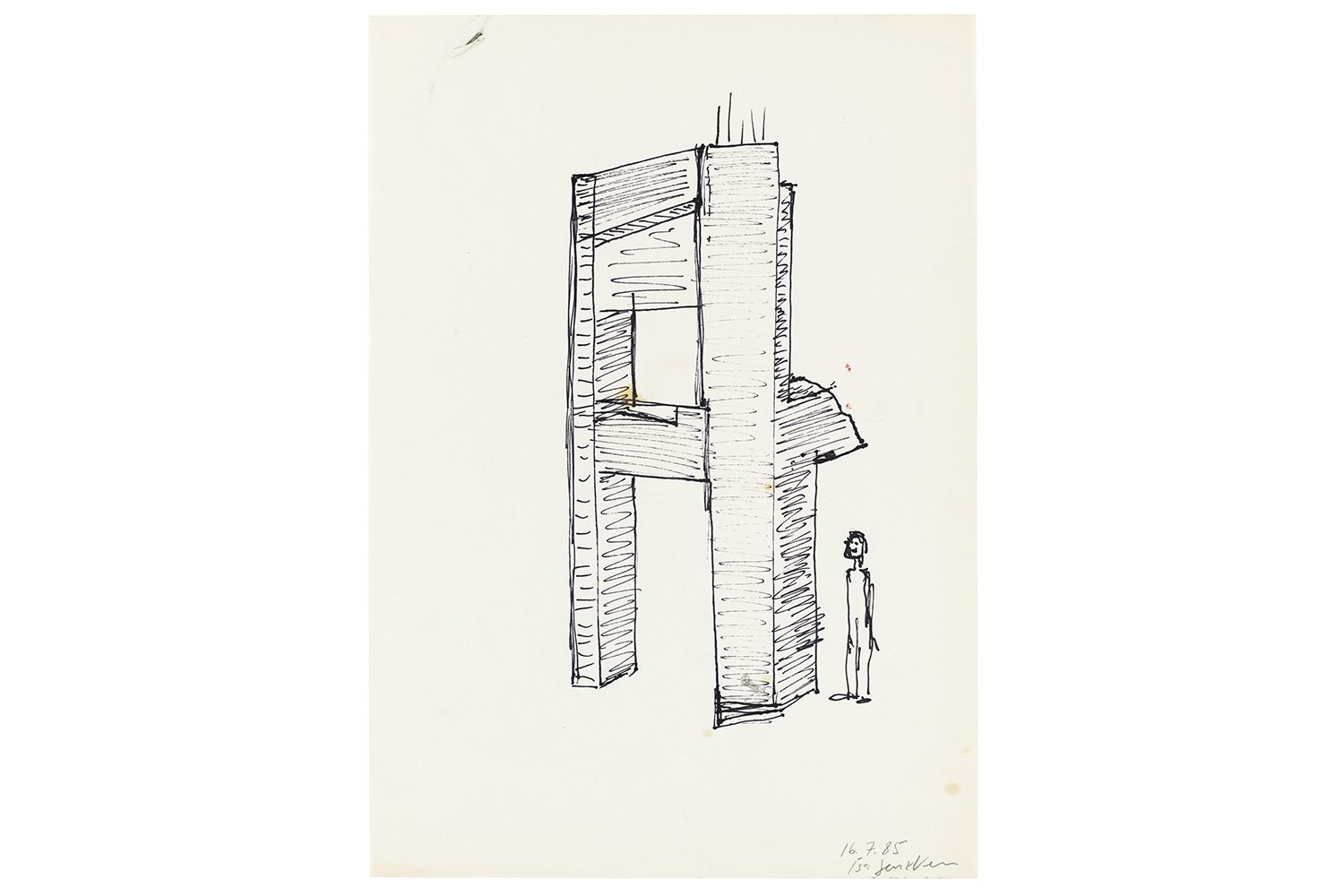

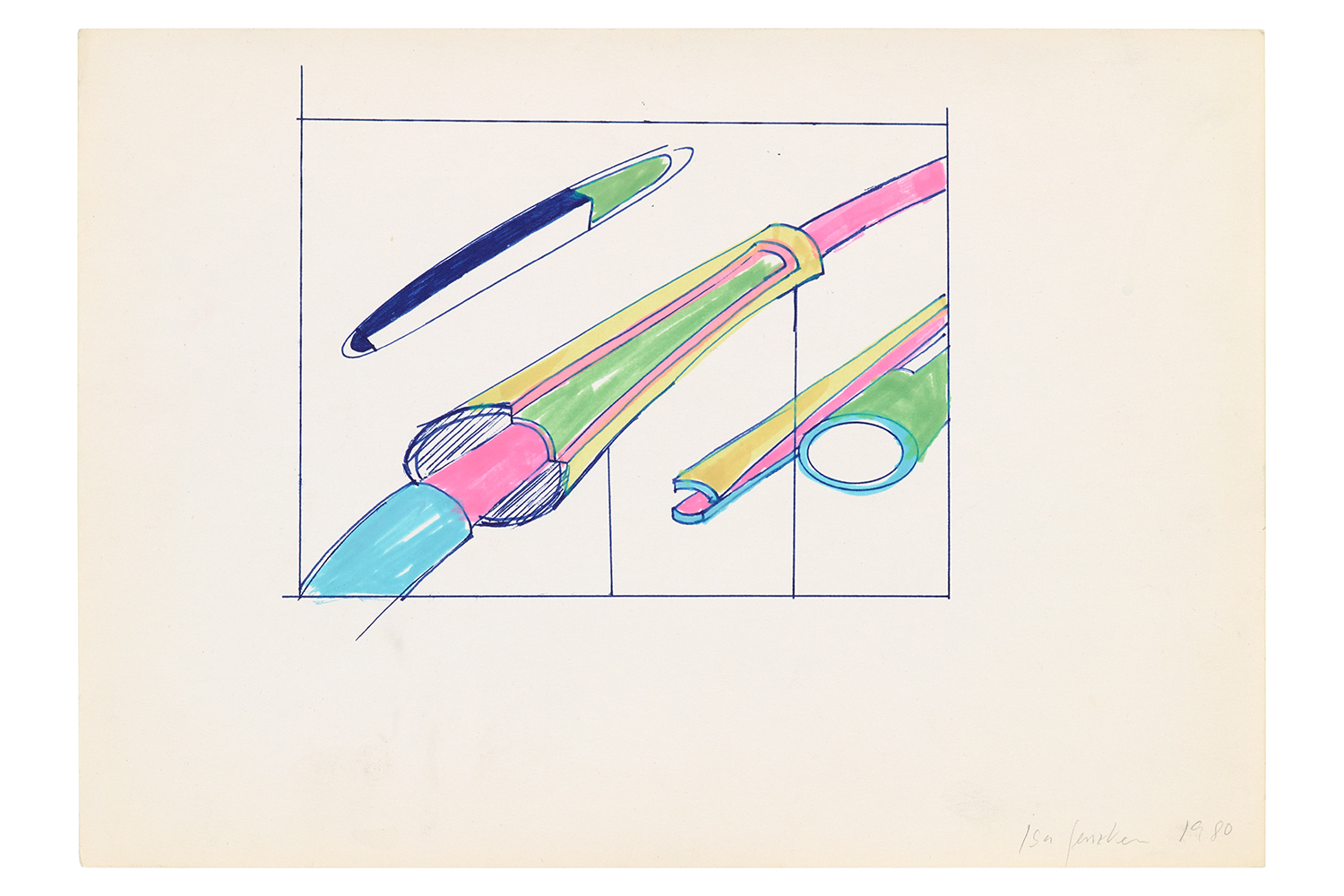

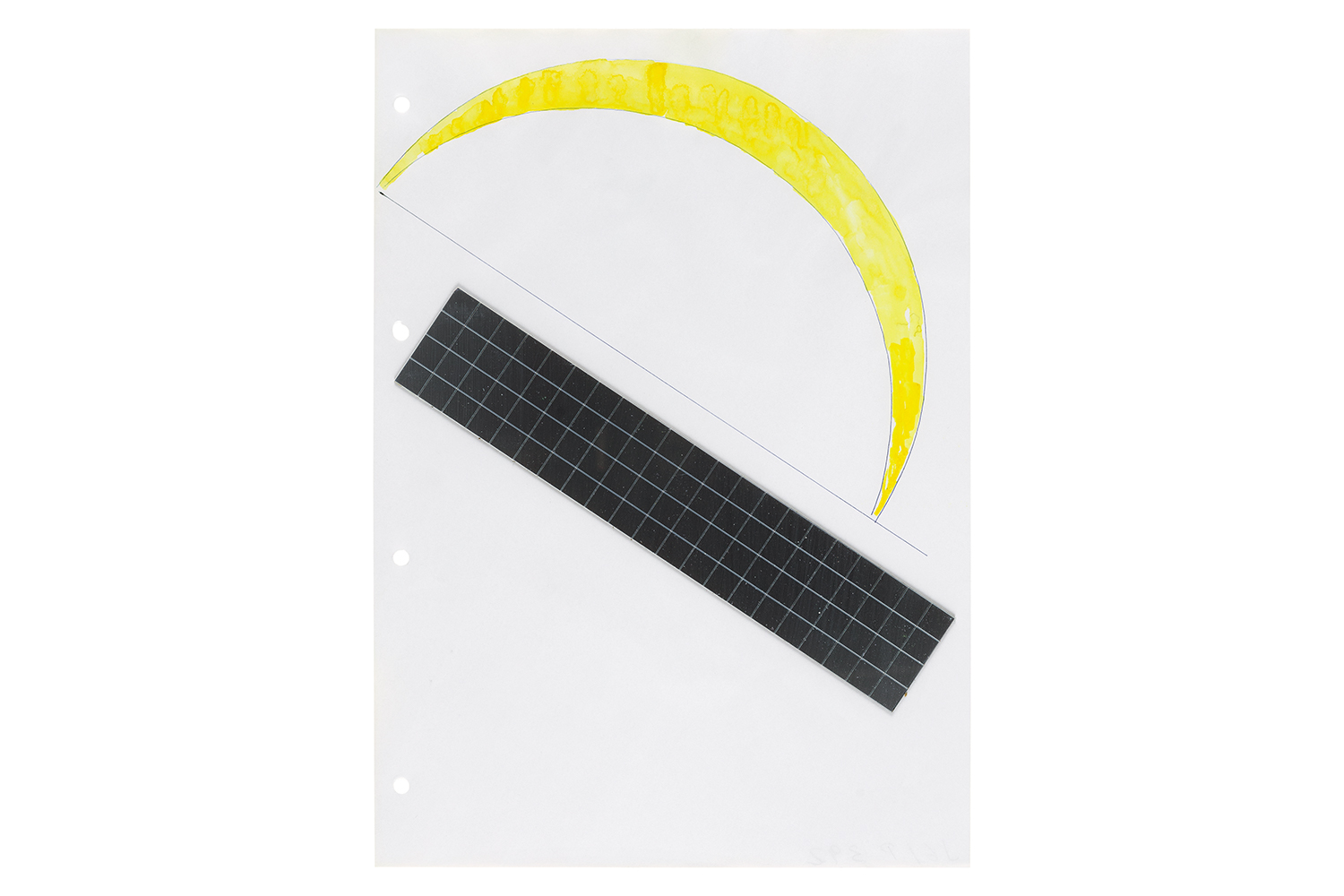

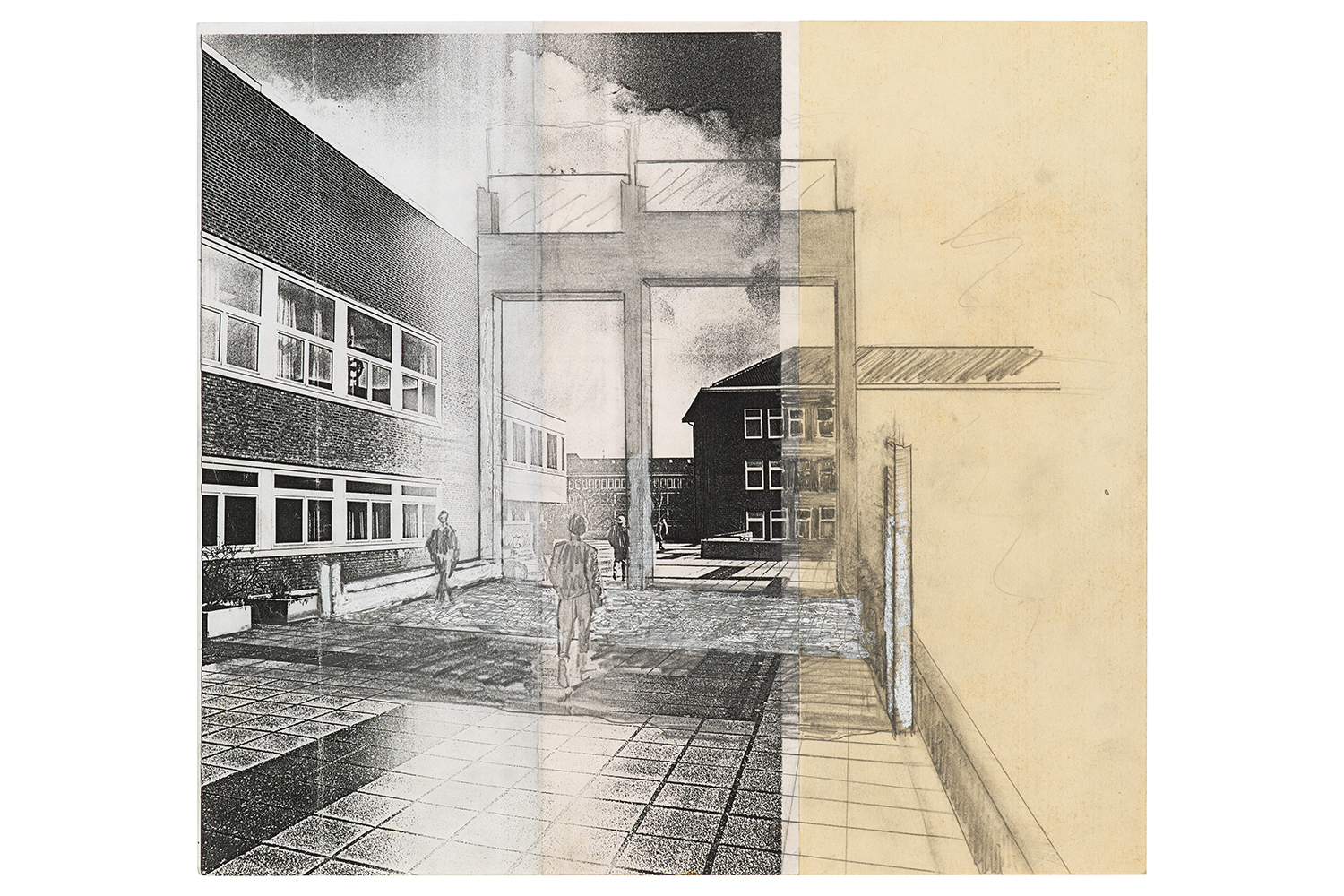

By the late 1970s, Genzken’s Hyperbolos and Ellipsoids series had attracted attention due to their engagement with Minimalist language and forms. Genzken was strategic in her making, opting into recognizable trends for visibility and acknowledgment while maintaining a distinct vocabulary of her own that made her stand out among a crowd. Her dialogue with architecture was similarly deliberated. Since the 1980s, Genzken has created sculptures that recall and reference urban landscapes and architectures while also challenging socially accepted notions of both. After making vertical, columned sculptures with materials typically used in architectural construction, such as concrete, Genzken began thinking more abstractly about building and foundations. Her series Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings for New York) (2000), for example, represented the artist’s first foray into handmade assemblage.

Using found materials and what would be considered waste or debris by most, Genzken handcrafted rough and haphazard structures that offer an opportunity to reconsider the materials that comprise the building blocks of architectural constructions. Her nonsensical and somewhat intimate assemblages — made from detritus that touches the hands of many before ending up in the trash bin — reconfigure our understanding of public architecture and its components, and attract universal appeal.2

Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings for New York) marks a pivotal moment not only in the artist’s career but also more broadly among the contemporary art landscape at the time. As art critic Peter Schjeldahl noted in his review of Genzken’s MoMA retrospective in 2013, “‘Fuck the Bauhaus’ proved3 to be the starter’s gun for a movement.” The “movement” he refers to was that of a group of young New York artists, such as Rachel Harrison, compelled to make assemblages of various forms. This mode of making was eventually defined as “unmonumental sculpture” in the New Museum’s signal group exhibition “Unmonumental: The Object in the 21st Century,” in which both Genzken and Harrison were included.4

Like Fuck the Bauhaus (New Buildings for New York), all of Genzken’s work has encouraged audiences to question and expand their worldviews in different ways. Her major solo exhibition at the German Pavilion in the 52nd International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale in 2007 exemplifies the artist’s tendency toward provocation. Genzken went for a holistic approach, so to speak, tackling the entire building rather than just the inside. The artist enveloped the pavilion’s exterior facade in scaffolding and orange plastic “safety fence” netting typically found at construction sites.

Inside the pavilion, Genzken gave viewers a glimpse into a startling future devoid of humanity. A crowd of suitcases stand unattended by anyone but a few owls strategically perched near their handles. An ominous collection of nooses hang from the ceiling. Astronauts lie on the floor and dangle in midair, surrounded by mirrors on all sides that create blurry reflections. Passersby become mere ghosts slipping anonymously through the mirror cracks, devoid of distinguishing features or uniqueness of any kind. This slithery effect embodies the notion of going “under the radar” and dialogues with the title of Genzken’s Biennale contribution: Oil.

Commenting on the exhibition’s title, Genzken notes, “That is what the whole world is about. Whether there’s war or not, that’s what it’s all about. Energy and oil. You’ve simply got to understand this.”5 While Genzken directly calls this highly disputed resource into question — the artist is known for her critical and political lens — she also plays on oil’s inherent properties to make a larger comment about institutions themselves and asks viewers to consider different facets of power and how they order our world.

The artist’s allusions to transportation, velocity, and anonymity, for example, give form to oil’s slippery nature and recall French anthropologist Marc Augé’s theory of “non-places,” which he suggests are spaces like supermarkets, airports, highways, and gas stations — chronically homogeneous, increasingly impersonal, and discouraging to human connection.6 The exterior scaffolding, on the other hand, exists as a site of duality, holding as much potential for development as it does for ruin. When considered within the context of the art world’s contemporary landscape as well as the context of institutional critique, Genzken’s choice to confront her audience with an ambiguous rather than concrete setting serves as a poetic meditation on the ever-pressing need to reconsider and revise power structures. As museums and arts institutions of all kinds attempt to adjust their hierarchical anatomies, controversial biases, and more in the wake of 2020 and the innumerable questions it posed through its varied waves of unrest, Genzken’s 2007 provocation becomes even more poignant. The artist asks us to grapple with what it is that we glorify, what we see as worthy of being exalted, and why. She urges us to reckon with complexes of power and to address our collective potential to break them down in the name of building better ones up.

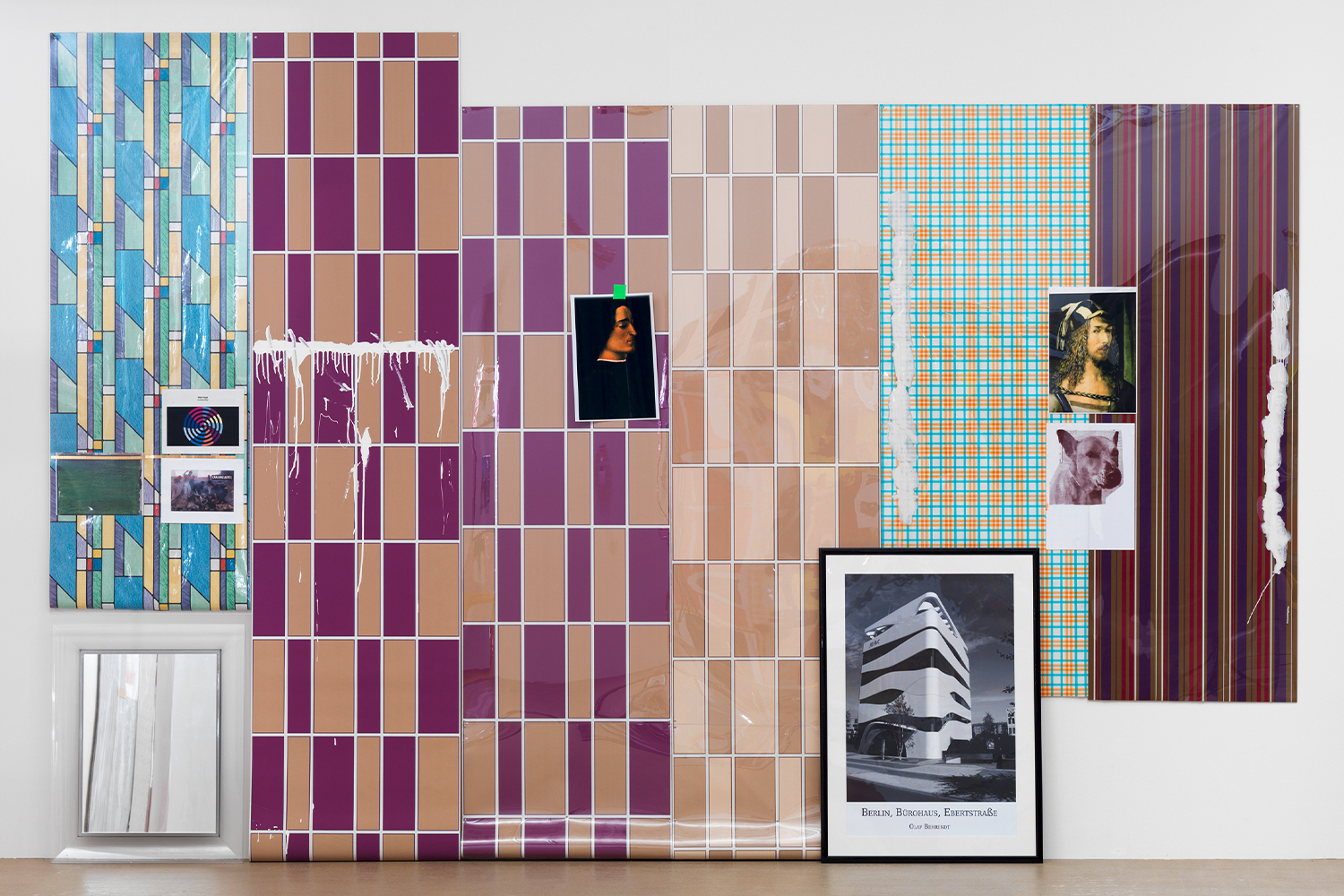

These themes return through the artist’s use of materials such as artwork crates, this time with a focus on institutional collecting and storing practices — a topic plaguing museums across the globe that have, in recent years, begun confronting questions of deaccessioning and ethical archiving and object accumulating policies.7

Despite the intensity of Genzken’s thematic inquiries, the artist maintains a consistent sense of humor made palpable through her often flamboyant, cheeky, and extravagant combinations of objects. From figures clad with far too many layers of clothing and accessories, including fake Hawaiian leis, bowler hats, plaid shirts, and costume masks, to sculptural assemblages comprised of empty pizza boxes, fan blades, and oyster shells, Genzken eschews a minimal approach in favor of a maximalist mindset and leans into the absurd, ridiculous, and outrageous. On the surface, the artist’s works are comedic, goading viewers to ask themselves if they are taking themselves too seriously and to chuckle at what society has become. The humorous dimension of Genzken’s work is purposeful and functions similarly to how artist Francis Alÿs has described the role of humor in his own practice: “Humor helps to catch the spectator’s attention… [It also] has a critical dimension… Humor is a double-edged weapon.”8 By including items made by recognizable brands, such as Crocs, and even banknotes and coins from across the globe in her assemblages, Genzken addresses themes of commerce and capitalism from a satirical perspective. These sculptures take on heightened meaning when displayed in institutional art exhibitions, probing how business and artificiality function in the art world.

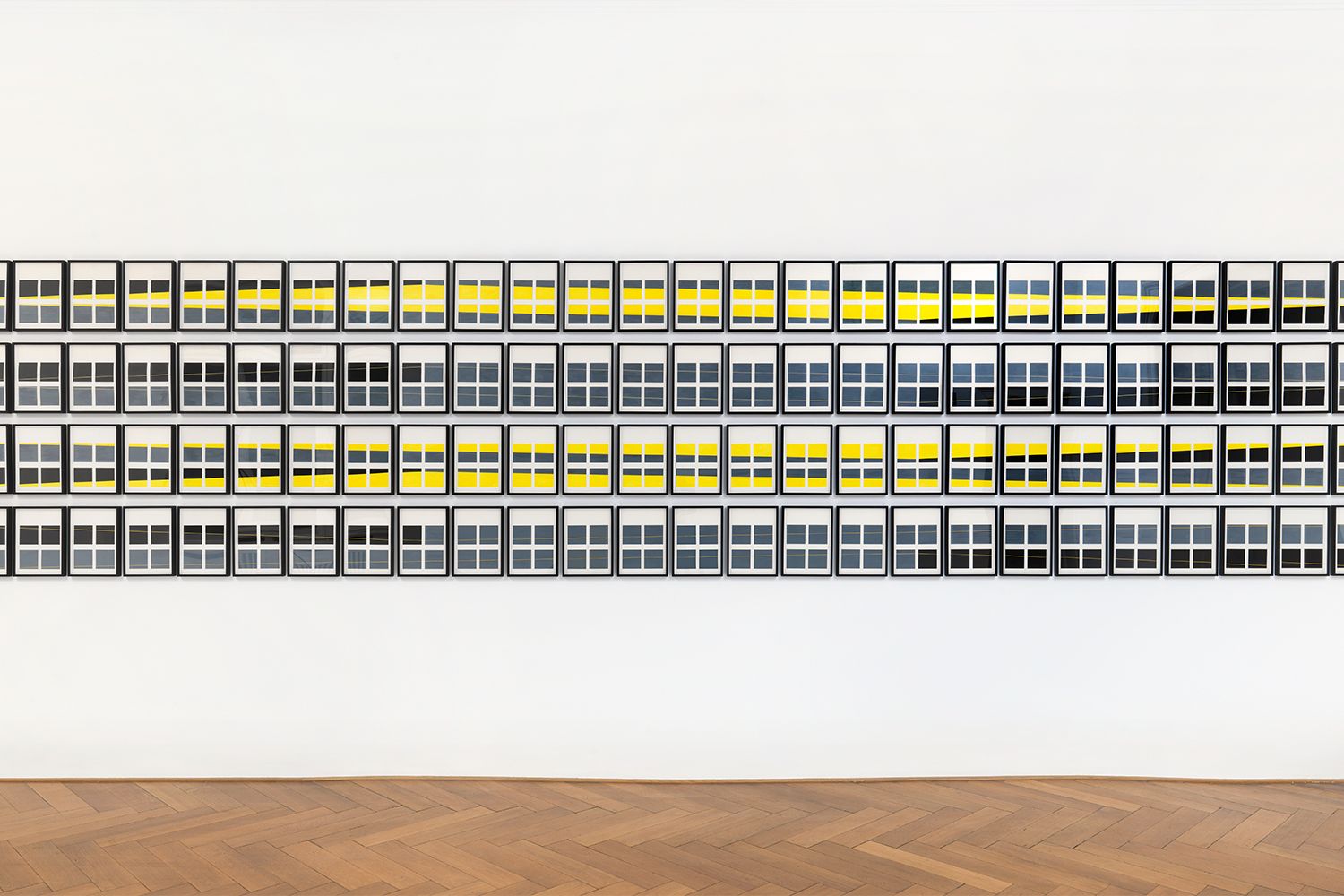

Genzken’s shrewd use of humor extends to her nonsensical applications of objects in her work. All of the items Genzken employs in her practice are decontextualized parts of wholes that are no longer functional or used in the way they are typically intended and prescribed. By utilizing these “useless” objects in her work, Genzken renders productive what would normally be seen as trash, junk, or refuse. They become queer objects, ones that, by nature of being repurposed in Genzken’s work, refuse to conform to societal norms and instead pursue their own divergent paths. In the most capacious sense, these items represent glitches in the systemic fabric of contemporary society, malfunctions within socially accepted and perpetuated ordering apparatuses.9 Genzken’s maximalist approach lends itself to the performativity and fabulous excess at the heart of Susan Sontag’s “Camp,” further queering her sculptural assemblages.10 The artist veers away from the predictable and status quo, alternatively choosing to celebrate and encourage an overstatement and exceptionality of forms in her work. The objects she selects and combines in her work form a motley crew that starts to take on a life of its own, introducing questions addressed by theorists of new materialism — ones of subjectivity and of how such nonhuman entities interact with and change the humans they encounter.11

Like Genzken’s queer objects, the artist herself has been othered and seen as an outsider due to her struggles with bipolar disorder and alcoholism. While, of course, significant to her overall story and oeuvre, critics’ attention to these personal details in relation to Genzken’s work may also account for her mixed reception over time and her delayed international recognition. Even in recent years, the artist’s solo exhibitions have mainly been held in Europe. However, none can deny the evergreen relevance of Genzken’s prolific and ever-expanding body of work. Across several decades, Genzken has managed to create thought- provoking art that rejects categorization of any kind and is consistently and refreshingly unique — rare in a world marked by sameness. Her oeuvre is chameleonic — constantly shifting and changing, refusing to sit still, and always finding new ways to dazzle, alarm, and instigate. Genzken is a visionary whose work inspires novel, nonlinear, and nonbinary thinking around cycles of history, systems of power, and human and nonhuman interaction and connectivity. Her work takes on some of today’s most pertinent and plaguing existential questions. Ultimately, Genzken asks us to reckon with the past and recognize how we as a society can dismantle harmful hierarchies and create alternate possibilities for our shared future, ones that are more expansive and ethical than anything we have achieved or envisioned thus far.