Nathaniel Mellors: We should talk about some of your work and the exhibition you’re working on for the museum.

Tala Madani: The current situation is so distracting that it’s very difficult to go to work. And because we work half days with the kids… I was thinking: What does the brain want in a situation like this? Does it want to focus on the trauma of the moment or just escape into something different?

NM: I know what you mean. But isn’t that something you’re juggling? Balancing in your work all the time?

TM: Sure. I’m always very aware of the mood of an environment, the mood of the culture, and I try to put the work in a frictional space in relation to it. The work appears because something inside of me is not in accord with my own surroundings. But now, this heightened level of global anxiety has really changed everything.

NM: Right, I see. So what you’re saying is that if your surroundings become more difficult then your calibration goes out of whack?

[laughter]

TM: Not that anything is calibrated, but —

NM: No, I mean the calibration that you have between your own interior dynamics and the exterior — how this gets harder when things get more extreme outside. Because you’re already dealing with some of the more extreme aspects of human behavior in your work.

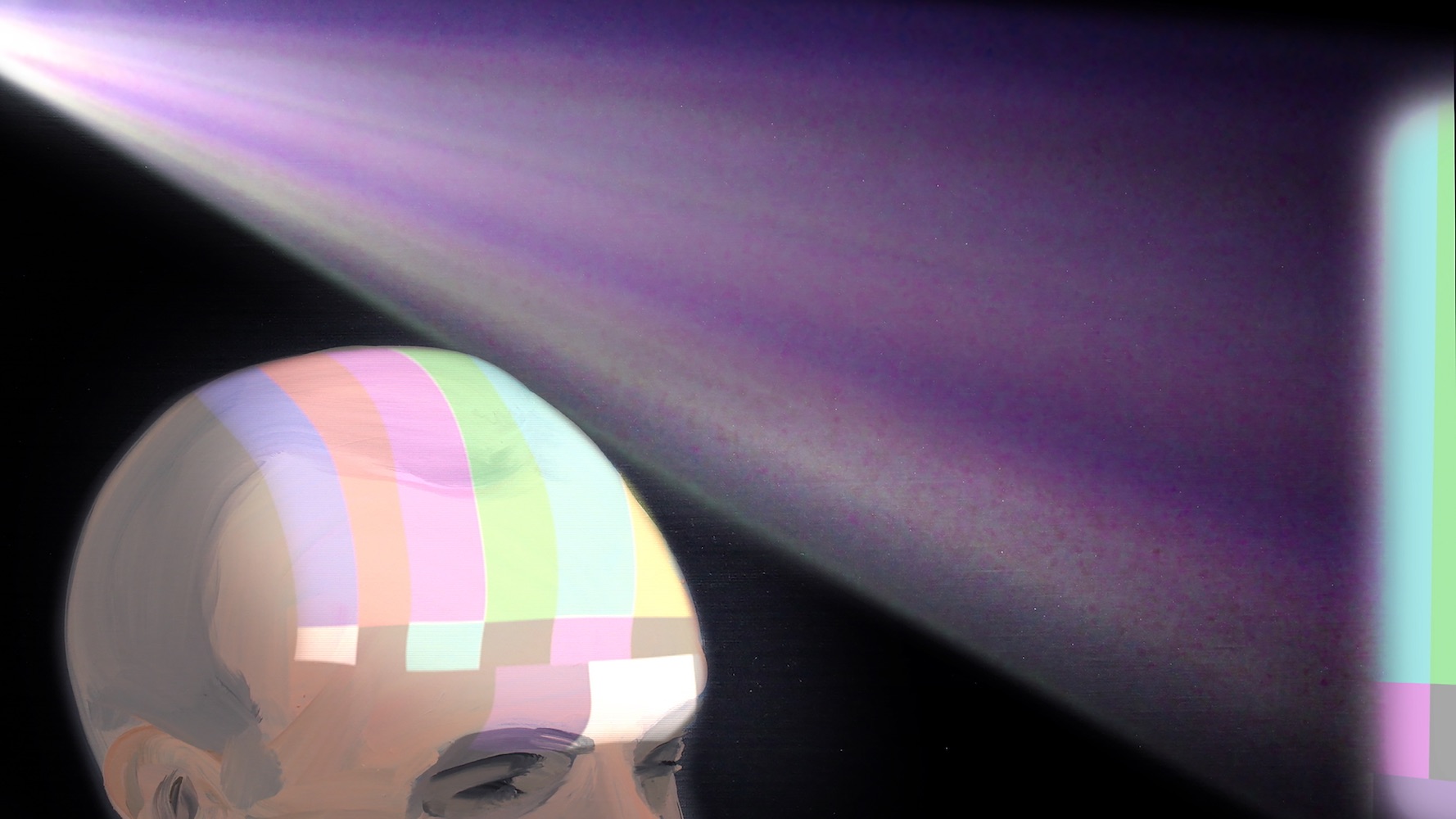

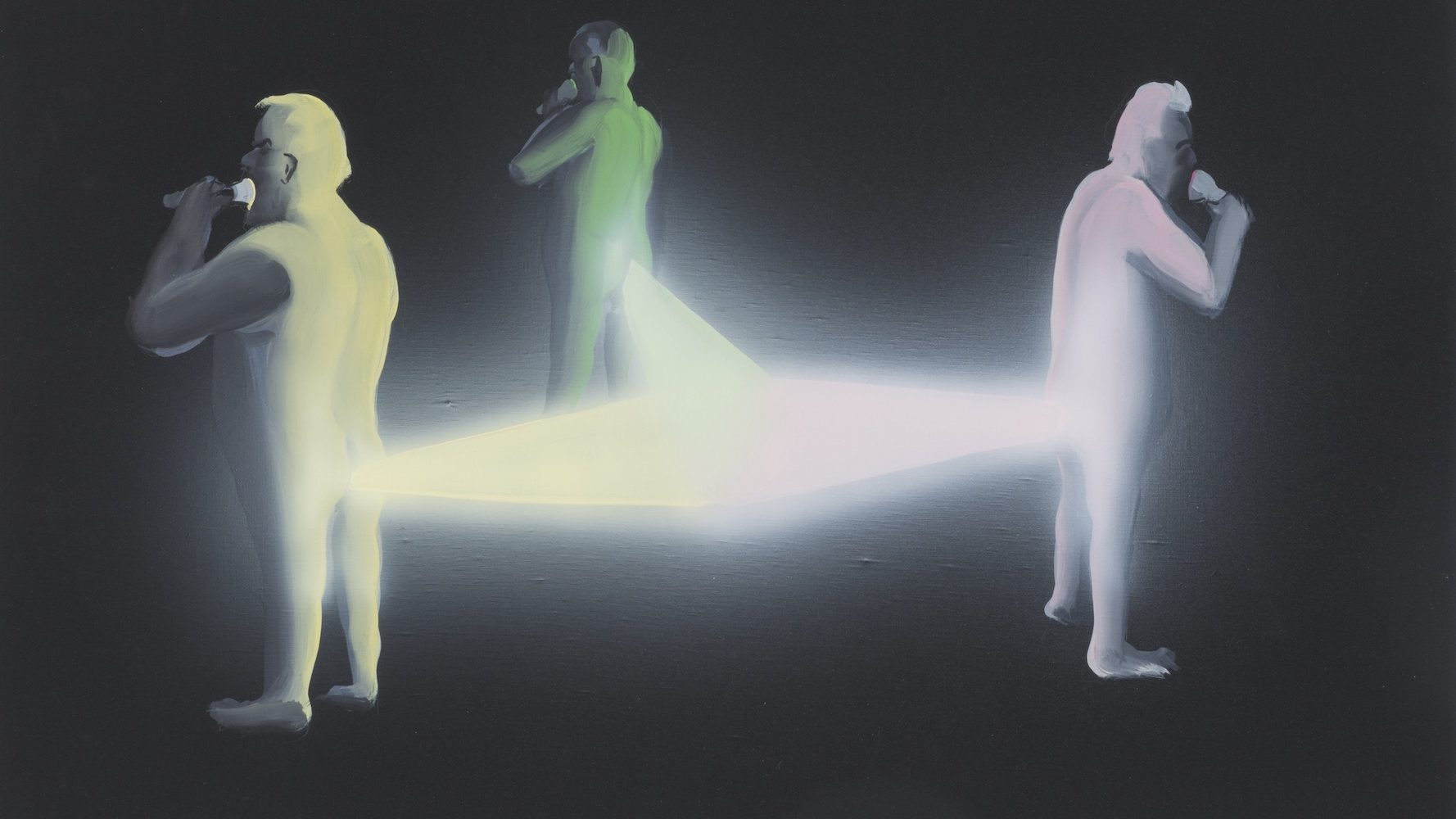

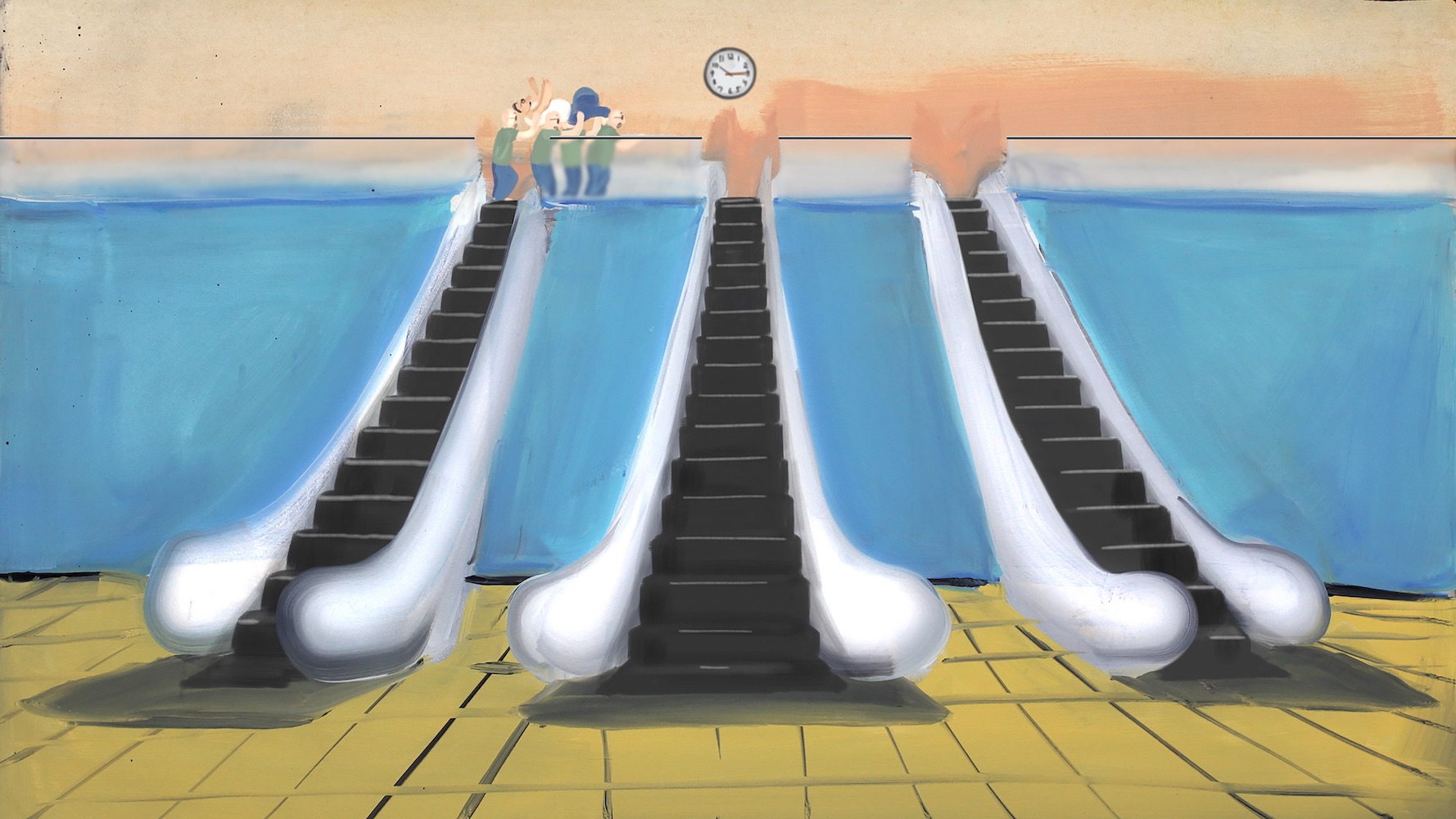

TM: Yes. There seems to be something on the surface that’s like a show of happiness, and now that’s being challenged by COVID-19. And the way I used to react to a Western presentation of this ideal was to show its holes. And now in the face of a lot of social anxiety, you sort of don’t want to poke holes anymore. It’s taking longer to find a focus at the moment. So I started making some paintings that deal with what’s going on very directly. Like, I started painting a mask. Or painting these fans — there’s something in the air that’s being moved around. Or some idea of the figure — the figures have become really insubstantial, they are so fragile…

NM: You’re painting with a greater sense of physical vulnerability than you would normally paint?

TM: Yeah.

NM: That’s interesting because I think you paint a physical vulnerability that’s very invulnerable. A lot of the figures are like cartoon figures that you can smash and break but they don’t die.

TM: They’re laughing through it and they don’t get upset by it.

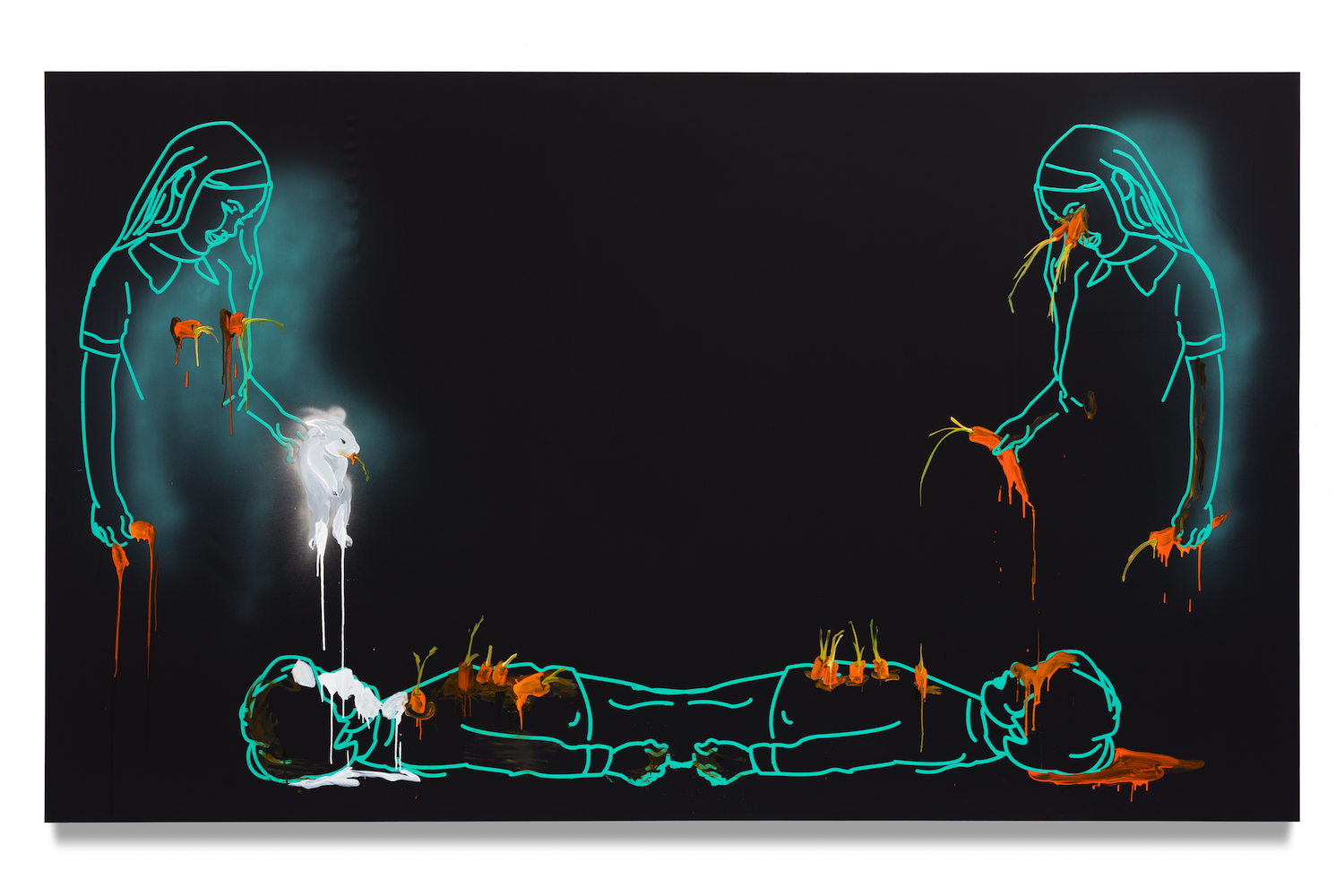

NM: Right, but I think death is in the work — it’s symbolized in different ways. There’s a kind iconography to it.

TM: I was for years really interested in the idea of suicide — the idea of chosen death. And now there’s this idea of massive global involuntary death. So even the idea of painting about suicide becomes quite questionable. Suicide is very alien to my own psychology; perhaps that’s why I’m very interested in the idea of choosing your own death, and the romanticism around that. I used to read some of the writings of Ali Shariati, who studied in France in the 1950s and I think brought existentialism and Islamic sociology together. Obviously there is a culture of martyrdom in Christianity and Islam, and then the private suicide…

NM: Is it something you feel critical of?

TM: I wouldn’t say I’m being critical of suicide.

NM: I mean the culture of martyrdom.

TM: Yeah, I don’t know if I’m being critical of it. I’m more… bewildered by it.

In the fan paintings, the fans are blowing the figure away, wiping figures off. I’m also making these paintings of cement grounds showing a shadow of someone on a roof, ready to jump, but what you’re seeing is the ground.

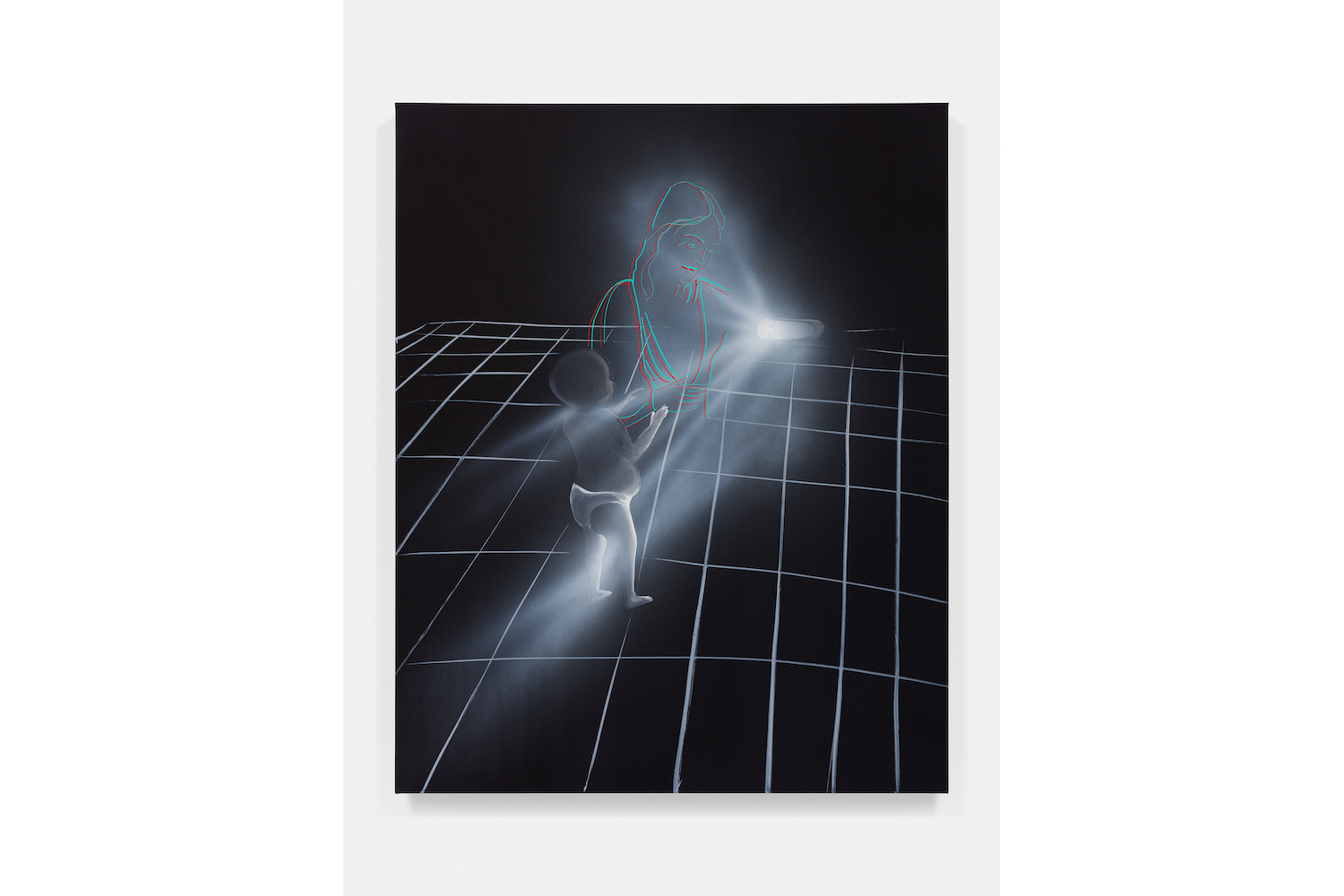

NM: So you’re saying that your sense of the physical is that it’s more vulnerable at the moment and you’re painting figures that are more fragile. But I noticed that these more immaterial figures have been manifesting in your work over the last couple of years. Like these ghosts holding babies — ghost mothers, ghost fathers, figures that are almost like gas clouds or vapors. These are some kind of symbol of death or some highly marginal form of human life.

TM: Yeah, those were also juxtaposed with baby paintings. And this thing with COVID and age — it doesn’t touch kids, thank god. Mostly not.

NM: Right.

TM: This does create two different experiences for two different age groups. In a lot of mythologies, are the young people going to kill the old people or are the old people going to kill the young? This is the fight of the ages: Will the old succumb to the will of the younger generation? Or will the young people obey?

NM: It never goes out of fashion.

TM: Right. Oedipus Rex — there’s so many examples. And now with young people fighting climate change… There’s a sad irony.

NM: Are you framing this as nature’s revenge? [laughs]

TM: Of course it’s terrible because the people with power will be protected more than the vulnerable. So it won’t work out in this mythological way. It won’t change anything unless we as a society demand it.

NM: A lot of working people, without understanding stock buybacks or the way liquidity is created through quantitative easing, are like indentured slaves to this system. When there are these systemic shocks, like 9/11 or the coronavirus, it feels like there’s the opportunity for a much more radical change, but it’s hard to overthrow the Old Gods.

TM: I feel we had a similar experience when we were waiting for our second child. I remember the only thing you could do was write music.

NM: Yeah.

TM: Can you talk about that? How you could only write music and then you couldn’t stop for two years?

NM: Yeah, I guess everything was on hold in normal life. The only creative channel that felt open to me was music. I always work collaboratively, and I realized I could work independently as well. I started drawing more on my writing. I always enjoyed writing lyrics — it’s like writing poetry without the expectations.

TM: I think you’re being quite modest about it because I think the album you’ve made is staggering, and quite an achievement. Like, it does things you do in your video work.

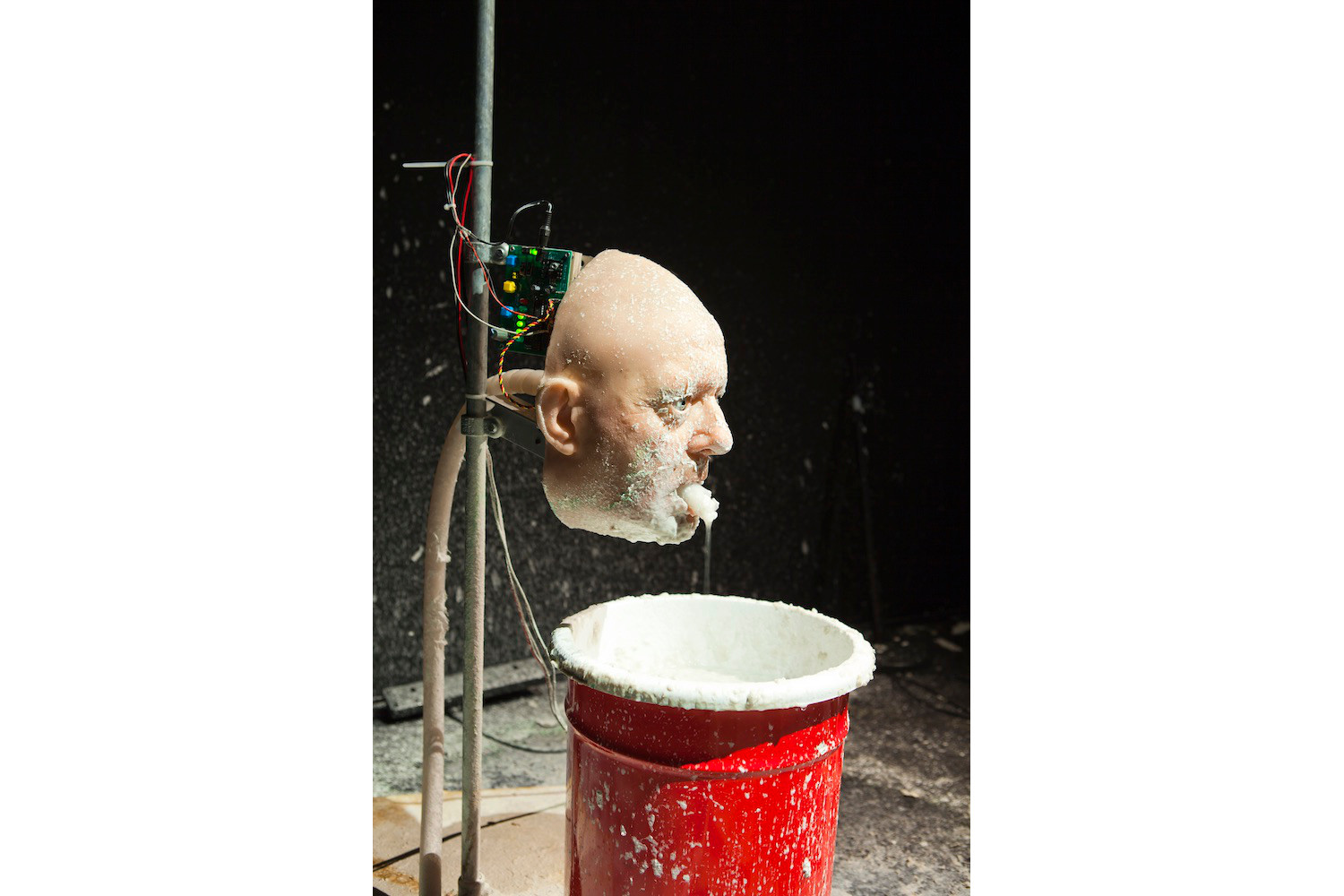

NM: I guess there’s always been this relationship with language that I’ve drawn on. Like, when I hit my own limitation with sculpture I turned to scriptwriting and making sculptures “talk” with animatronics. I like Jean Cocteau’s expanded definition of what it means to be a poet. I can draw on these things — my frustrations with class and power that inform my work, or a love of surrealism or absurdity. A song can be all these things.

TM: Right, and a song works on people physically.

NM: Without the physical it doesn’t exist. A record is a sculpture. It’s a physical carving. I wanted to ask you again about painting images that respond to this moment. Your work is always responding to social, political, and cultural things, but it’s not always easy to locate the specifics of that, so people often generalize when they talk about the content of your work. But in this case you’re painting more direct references. Is it any different — or not really?

TM: Maybe, like the P95 masks on the face will register. But in a few years it won’t again. So when I’m making the paintings it’s about the figure’s fragility. For me it doesn’t have to address the situation right now.

NM: That brings to mind… I’m sure there’s an interview with Francis Bacon where he’s saying a similar thing about hypodermic needles and swastikas. He deployed these very specific symbols, almost like punctuation marks that pull focus within the paintings, but at the same time they’re arguably even more abstracted than the figures are. There’s an oscillation between total specificity and abstraction in terms of what they are invoking. At the same time, the mask you’ve painted feels like a skull in this moment.

TM: It recalls a body.

NM: Yeah, yeah. I think generally you are channeling some fairly extreme content in ways that make it exceptionally palatable for people in a certain context, but it can still be carrying some horrific charge.

TM: What I’m not interested in is a kind of nostalgia in painting. Paintings that are interested in technique for its own sake, or that take pleasure in the way things have been painted — a nostalgic way of painting. The painting should have something that’s motivating it in the present and in itself — to have an interest in actually getting born, as an artwork, to be interested in becoming, rather than what has been. And you know the thing about creation: anything that is becoming is messy, it’s forceful. There can be this energy of being present with a work that is trying to actually become something that hasn’t been. It’s not about newness for the sake of newness again. It’s not about new technique. It’s just about really being present with the work itself.

TM: I came across an essay about empty cities — about turn-of-the-twentieth-century industrialization and populated cities and artists being disgusted by it to the point where Odilon Redon is wearing opaque glasses in the city so reality won’t change his memory.

NM: Really, like he’s wearing some kind of exterior reality filter?

TM: Yeah, and a lot of artists chose to paint these big capitals devoid of humans, to celebrate a lack of human presence in this moment of human overpopulation.

NM: These Romantics have to be careful what they wish for! I was just recording a new video introduction to an old work of mine today, Giantbum (2008), about a group of explorers who are lost in the bowels of a giant, and they are starving to death and they resort to cannibalism and coprophagia, eating themselves, shitting themselves out and rebuilding themselves. But the real point of horror in the script is when they are told that the giant they are lost inside has no outside. They cannot escape because there is no exterior to the system they are stuck inside of. It’s a permanent interior. And I wrote this to try to reflect on the way we were buying into these hermetic, mediated realities in the wake of Iraq and political spin… and now it’s twelve years on and my worst character in that — a coprophagic Pere Ubu — is less horrifying than Donald Trump. It’s like when we talk with Paul McCarthy — there was this observation, that I think Bruce Hainley made, that over a period of time the world has become more like Paul’s world. So where does an artist go from there?

TM: I wonder if it makes you hate your own work, because it’s even more real now.

NM: I think you can’t go further. I mean, it can’t be an inflationary game. Or can it?

TM: In terms of making work under these circumstances, it’s very difficult to become conscious, to become very self-aware of where something starts and where something ends. Except that I think I do definitely work from a charge in the studio — an emotional charge. And sometimes it’s about having a charge, starting something and then having the object of the painting reverberate, or give you back a charge while you are working.

NM: Right.

TM: Which is not very often, but I guess that’s the way of feeling that something exciting is happening — when there’s a reverberation from the painting back to me.

NM: Your emotional charge is quite constant, don’t you think?

TM: Well, it has to be there. That’s the interesting thing about studio practice — that you learn to do something. You learn to put yourself in the state of that charge.

NM: Right.

TM: It’s funny — we keep coming back to music. A lot of the time that’s through music, for me too.

NM: Yeah, but don’t you think the music’s a trigger for something that’s —

TM: — already there?

NM: Yeah, that’s imprinted in you.

TM: Oh yeah, absolutely. The music is a knock at the door: that can come in now.

NM: This comes back to some stuff that is like, “Where does all this shit come from?”

TM: And I think for artists a lot of the time it’s about sublimation.

NM: And people want to know. This is where a lot of interviews with you flounder, I think. People try and ask questions that are more or less badly disguised versions of “Where is this all coming from?”

TM: It’s really interesting: as we’re talking right now I’m looking at you and you’re wearing a shirt that we got from a friend of ours, the artist Mr. Fulton Washington…

NM: [laughs]

TM: This is not a pivot! You’re wearing this T-shirt of him, and it’s a painting of him that he made. He was in prison and he taught himself to paint and painted a picture of Obama giving him clemency, and Obama shortly afterwards gave him clemency. He’s a brilliant artist. And when we talk about paintings, he always says that when we talk about things images just come into his mind. I think for a lot of painters images just come from their minds, from their brain. I always responded to this notion that Nabokov put out, that a work of art or fiction is like a chess problem. The problem is not between the elements in the painting. The problem is between the painting and the viewer.

NM: Yeah, that’s way too much effort for people.

[laughter]

TM: I don’t think that’s true. I just think that people are not given enough of a sense of confidence to know that they are the holder of the artwork. I think people feel like they have to have some entrance to the work itself…

NM: No, no, I mean, I think that’s true, I agree with you. I was being facetious. I think that’s why great artworks are unanswerable: they continue to generate information, cognitive dissonance, into eternity. We can see that with artworks that are already hundreds of years old, thousands of years old, or forty thousand years old in the case of some cave art. So I totally agree with you, but I guess I was just observing that people will continue to ask the supposedly “dumb” question. It’s reasonable because they are trying to scratch that itch.

TM: I think the idea of death is going to be around us much more now. I think it’s going to be harder to take it in an artwork.

NM: But people aren’t engaging with death predicated on the idea that there’s no art around. It’s —

TM: — always around us?

NM: Yeah, it’s constant.

TM: Yeah, but that’s the thing right now. The media is making it feel like it’s knocking on your door.

NM: That’s the weird disjunct of this thing. It’s almost like being in Stalker by Tarkofsky. This idea that there’s this entity or something that’s there and you’re in The Zone, and you’re not quite sure…

TM: I was thinking that. I was thinking about Lem’s Solaris and the water, the wave…

NM: It is Solaris-like. Solaris might be a better reference point. The range of possibilities with this thing — it can kill you in the most extreme way, only if you’re old but maybe if you’re young. And you might have it or you might not. You’ll know about it but you might not know about it.

TM: You might also carry it.

NM: And by the way, we haven’t got the facilities to test you for it!

TM: What a joke.

NM: It might die out in the summer, but it might come back as well — forever! And you may or may not be able to get it twice.

TM: It might mutate.

NM: It’s almost like the sum of all fictions — of Western eschatological fantasies around viral death. I think this is really interesting. And this is not in any way to diminish the reality — people are dying and this is real — but it’s to simply observe that there is this enormous space between the facts of the thing — which we are trying to work out — and what is being projected through social media and news media. I don’t think this thing plays out like this at all in the early ’90s or any time before that.

TM: This idea — that with social media the public is weighing in on this and the policies are based on the public’s pressure through social media — is interesting. It makes it more democratic perhaps.

I think these governments will quite quickly flip the narrative of the coronavirus to support this nationalist populist agenda, like he already did calling it the “Chinese Virus,” when in fact the response was so weak because of this abandoning of international cooperation and all the federal agencies that could have worked together.

NM: Yeah, it totally exposes the fallacy of nationalist populism and really any political narratives that deny society or deny a bigger human environment that we all exist within. I always loved that Mark Fisher quote, that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. But on the other hand, at the moment, if capitalism is a car it looks like it’s only taken one nail to slow it down. But of course what we’re witnessing now with these bailouts is the totally unimaginable force that kicks in to make sure that this all remains intact.

TM: I think even with friends it’s a change in lifestyle that they wouldn’t have chosen, yet it’s giving them opportunities they wouldn’t expect, like spending more time with your child, with your family — things that are so good for your soul. But a lot of people’s lifestyles — they can’t afford these things anymore.