I am sitting on the bank of the River Ganges and I am stuffing everything I see into my head… I am eating it all, I just swallow it all down… I have a labor-like cramp, I feel as though my intestines are being prolapsed into the river… What is coming out of me is being washed away by the constant current.

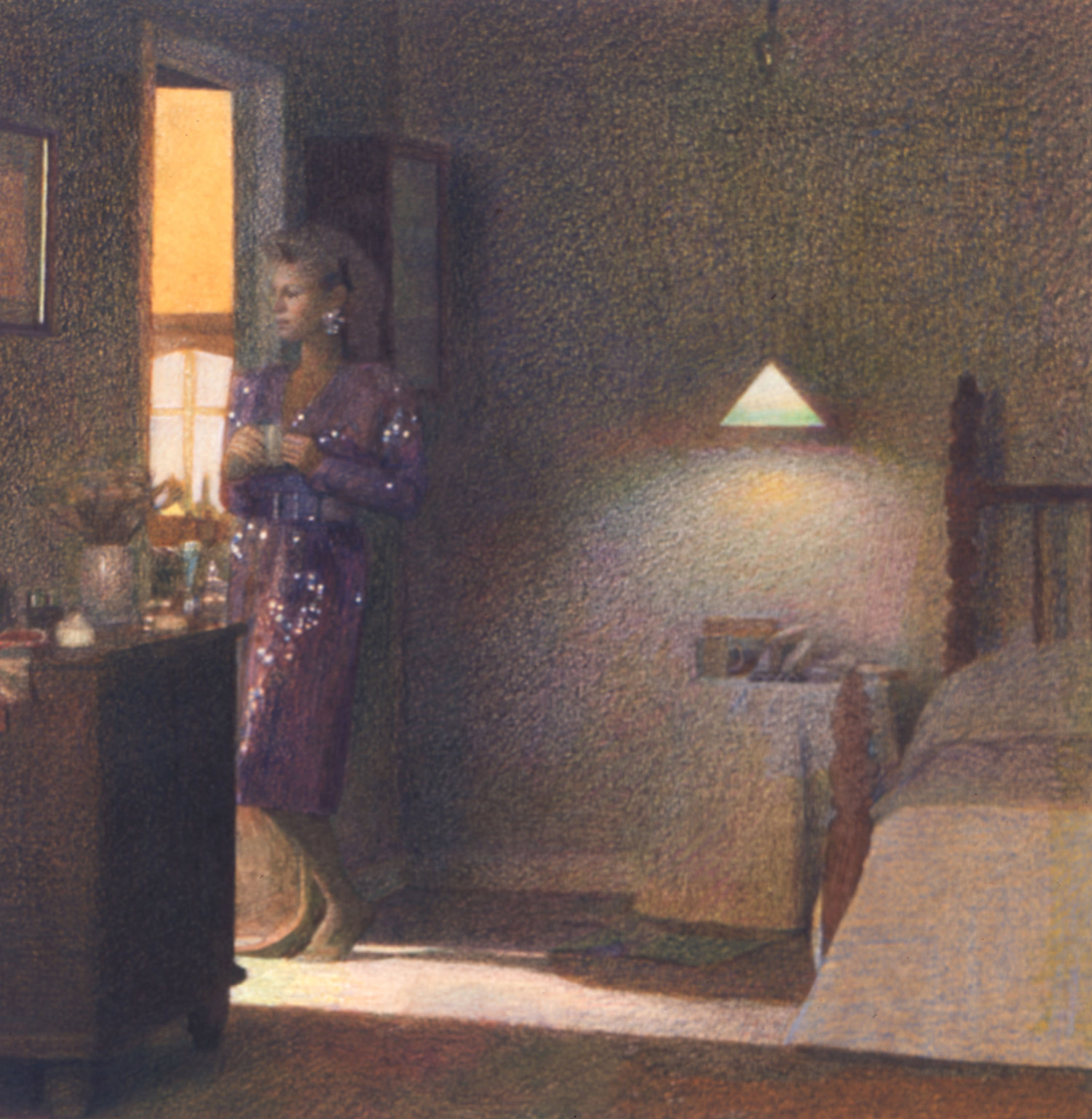

I wake up, and my stomach turns. I slowly realize that I must have eaten everything in my hotel minibar and on the fruit plate the night before, after taking two Ambien to finally fall asleep. Malaria prophylaxis pills often induce nightmares and may lead to a lack of sleep that enhances the dizzy feeling of jetlag and disorientation that comes with traveling. I had just arrived in Mumbai and checked into my hotel room, well-equipped with all kinds of inoculations, antibiotics, and the knowledge to not incorporate, drink, or eat anything uncooked or carrying germs that produce high fever and brutal diarrhea in so many foreign visitors. I was even made aware of the risks of using tap water to brush my teeth.

My hotel room overlooked a large open urban plaza in front of the Gate of India. Through my alcove window I could see that swarms of pigeons flew their rounds directly in front of the hotel. By the law of centrifugal physics it happened that one pigeon’s droppings splashed against the glass that separated indoors from outdoors. This rare coincidence of ‘it happening’ and ending up on my window drew my attention to the fact that all of these pigeons must continuously drop a lot onto this central area. I followed my curiosity and looked further down onto the plaza. I was shocked to see numerous homeless people and handicapped beggars sitting on top of and basically underneath the film of what that the birds had left there.

Re-reading the influential 1978 book, The History of Shit,1 by Dominique Laporte, one might be tempted to irresponsibly summarize it into a description of civilization as the process of rarifying waste into value, or more plainly, making shit into gold. The paperback edition of Laporte’s book has on its monochrome golden cover a simple oval white opening that inoffensively suggests the association of a bodily orifice as a portal into and out of the content of the book, between the front and back covers. Books are physically dry, and as the aforementioned book itself states, they do not really have a smell. Art often seems dry too, and it very rarely has a scent.

The purification implied in attempts to achieve ideals of truth and eternal beauty correspond with Freud’s three parameters of the progress of civilization: “beauty, cleanliness, and order.” 2 Those works that do have a natural odor are outstandingly unconservable, like Dieter Roth’s sweet-smelling chocolate, or his rotting cheese works, for example. At his notorious 1970 exhibition at Eugenia Butler Gallery in Los Angeles, “Staple Cheese (A Race),” Roth packed about 40 suitcases full of cheese; with time, flies and maggots assaulted the art works.

Just as Roth elbowed rancid cheese into the realm of art, perhaps the most literal translation of the shit-into-gold concept in an artwork is exemplified by Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (1961). The 30-gram can of the artist’s own human waste was transubstantiated into commodity, and Manzoni determined its price according to the current market value of gold. Today its value surpasses the equivalent in gold, and as a rarified iconic piece, it could nearly exemplify the whole late 1960s/early 1970s methodology of claiming to liberate the personal and the cultural, the private and the political, and the physical and mental limitations of our concepts of modern life.

In 1965, Shigeko Kubota created a painting with a paintbrush attached to her vagina, and in 1975, Carolee Schneemann performed Interior Scroll and read from a piece of paper while slowly removing it from inside herself. Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s actions suggested brutal physical self-mutilation, and in Otmar Bauer’s 1970 film, Otmar Bauer Presents, the artist repeatedly consumed his own excreted bodily substances from a plate, onto which his reflexes catapulted them back out, over and over again.

Working almost three decades after Manzoni, Tom Friedman’s Untitled sculpture of 1992 literally placed a piece of feces on a pedestal. In its miniature scale, isolation, and perfectly spherical form, it became neat, clean and in this sense ‘suitable’ for the realm of art. With Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca (2000), the excrement-producing machine, the process of digestion is completely mechanized; made of stainless steel, the contraption renders the means of excretion tidy and odorless.

In the wake of Freud’s distinction between anal expulsive (reckless, defiant, messy) and anal retentive (withholding, meticulous, careful) dispositions, these works comment on the rigid standards by which human waste can accrue value in society and in art. From Kiki Smith’s unraveled Intestine (1992) made of bronze and Digestive System (1998-2004) made of ductile iron, to Michelle Hines’ s images of extrusion in World Record #4: Peristaltic Action (1995), to Jonathan Horowitz’s portable toilets Pissroom and Shitroom (2006) recently shown in the “Survivor” exhibition curated by David Rimanelli in New York City, and Lizzi Bougatsos’s Success!!! (2006), a likeness of excrement made of plaster with paint and gold leaf, the biological left-over is a theme that continues to pervade contemporary art. As in Laporte’s study, these works describe the vestiges of a living existence within controlled circumstances, once again making value out of waste.

Waste can be a weapon. In her 1997 performance El Peso de la Culpa, Tania Bruguera enacted an indigenous Cuban ritual of protest, in which a person would consume dirt to the point of fatality. To commit suicide is viewed as the ultimate act of resistance. Coinciding with the several-day-long symposium at the local National Gallery that had brought me to Mumbai was the 2004 World Social Forum, a counteractive response to the World Economic Forum. The World Social Forum took place in a large area frequently used for fairs, situated halfway between the city center and the airport.

On our way there, the shuttle bus dropped the curators off at a parking lot across the highway. Separating the fairground from the main highway was a little canal. On either side of it, little settlements had been constructed out of black plastic garbage bags as a shelter for local families, protecting against sun and rain. After jaywalking across the multi-lane road, we stood amidst residences and families’ daily routines: children were combing each other’s hair, and parents were busy washing dishes or preparing for a meal to come. So as not to intrude, we tried to move a bit aside toward the canal, until we realized that it was basically a river of raw sewage. The casually detached misery of the people we had tried not to disturb was positioned right up against the polluted canal — a literal cloaca of these slums.

When we entered the fairground, a stronger wind came up. Dust swirled through the air and one felt that it was unavoidable to breathe in the particles that made that wind so tangible. The recent memories of the little sewage river next to the fairground were becoming more present, and the curators were seen holding handkerchiefs in front of their mouths and noses to prevent all the little dusty particles from entering their bodies — but the dust was dry.

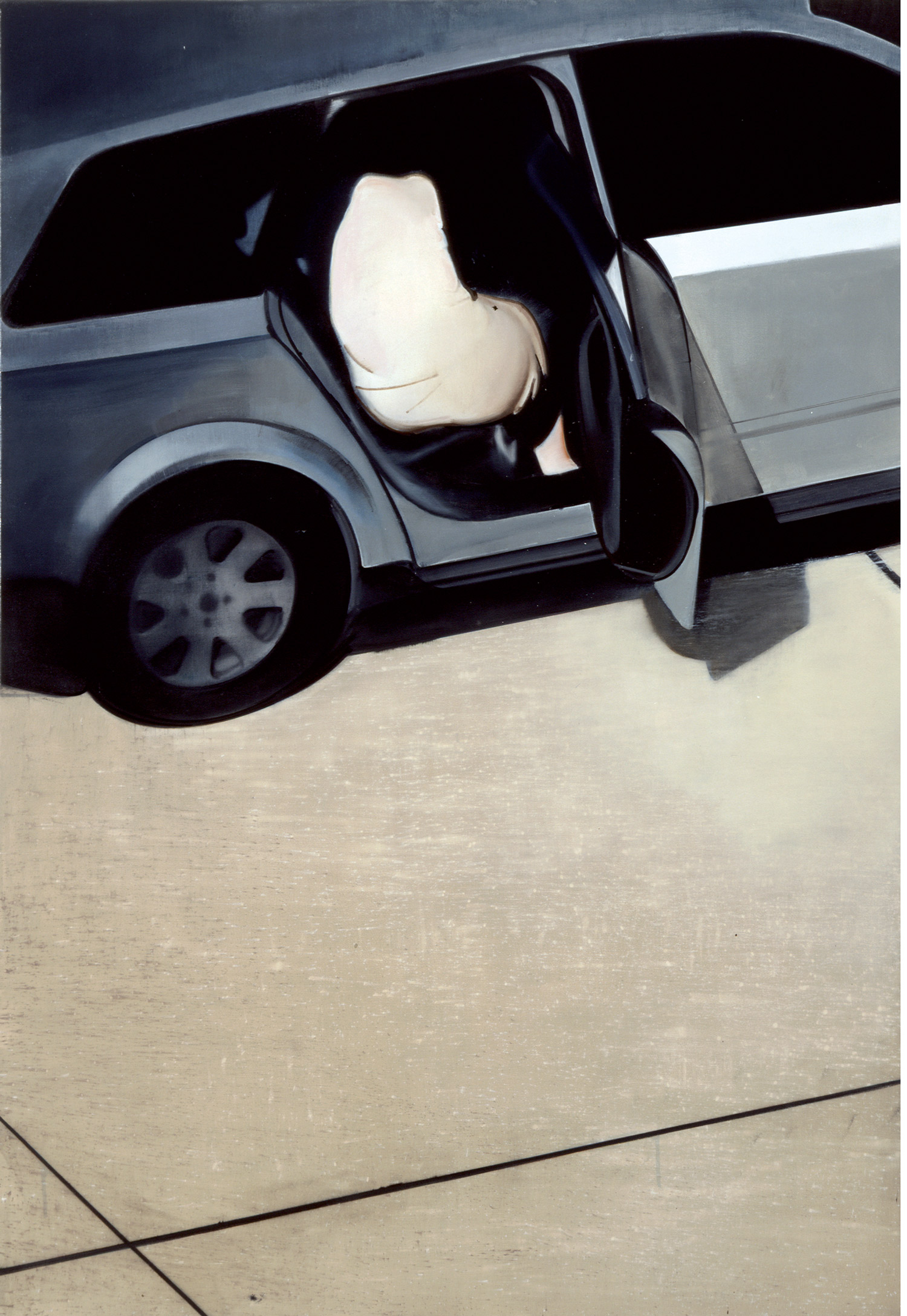

Modern life in economically stronger countries seems to be free of any unwanted points of contact with bodily fluids and other forms of physiological wetness. The white cubes of contemporary architecture and the refined cleanliness of metropolitan cities have banned anything visceral from our daily visual or olfactory repertoires. Different cities maintain different levels of sophistication of this absence: Tokyo is so clean that one is not even expected to touch the door handle in a taxi, and New York is fairly clean, while in Berlin there are traces of dogs left all around the city — which would seem to be nearly as scandalous for Tokyo as if there were corpses lying around on the street. Are there corpses lying around on the street anywhere still? (I had feared that I would see corpses on the street in India but even my malaria pills couldn’t make me see that.)

At least nearly all bigger urban areas have established systems where there is no more than the occasional delinquent occurrence of visible human waste in the city, in unguarded corners of parking lots or underpasses. In general there is no space for the humid nature of the human body aside from restricted, designated areas like the institutions of toilets, hospitals, pools, etc. This cleanliness has been manifested as a nearly hysterical phobia of germs. Entire industries are in existence based on this fear, sustaining the market of bleaching, disinfecting, and sterilizing everything all at the same time.

The setting of the World Social Forum alone proved its point. With an attendance of up to an estimated 100,000 persons at any given time, the reality was that this congregation of people wasn’t just another Woodstock. The exhibitions held within the monumental World Social Forum didn’t need to include any work about explicitly reintroducing the physicality of the body, since the larger context in which the exhibition was taking place was already devoid of this awareness.

The art works and documentations were successfully and not at all decoratively placed in the position of a visualization and comment on our global market and media spaces. The tension between the anticipation and active resistance was tangible, and the exhibitions discussed how to avoid simply adjusting to the ruling economic systems. The works confronted challenging topics like the post-colonial continuation of past patterns of exploitation, and also addressed ethnic, religious and human rights issues; among these were documentaries on the atrocities against Muslims in the state of Gujarat. These themes were essential in the various smaller shows that could be seen within the larger setting.3

Before I left, I saw the video piece Pure (2000) by the Indian artist Subodh Gupta. In this film, the artist himself is standing under a shower, only the more he tries to get clean, the more he becomes covered with shit. Suddenly I felt embarrassed, as I began to see myself in this revealing image. I felt as if it was a caricature of myself, an ignorant westerner visiting and exoticizing this beautifully complex country. I could not write off this attitude as another side effect of my malaria pills… I realized that I was not afraid of what was in the other, but I was afraid of what was in myself. But once again, to end with a quote by Laporte, “Where shit was, so gold shall be.” 4