Since the political upset of the American presidential election, journalists, academics and artists have been working to make sense of its unexpected outcome. A commonly cited cause of the current malaise has been the unfolding power of algorithms, with one argument viewing Trump’s victory as the result of “smart” voter data management. From the early primaries onward, the Trump campaign team began gathering individual voter profiles to subsequently match different groups with the most effective ad. While such “microtargeting” is nothing new to campaigning, Trump’s team dramatically enhanced the success of this strategy by co-opting algorithms from consumer advertising platforms such as Facebook and Google. These commercial algorithms helped the campaign to not only identify a much larger number of user profiles but also made it possible to test out several thousand variants of an ad in order to further tailor the messages.

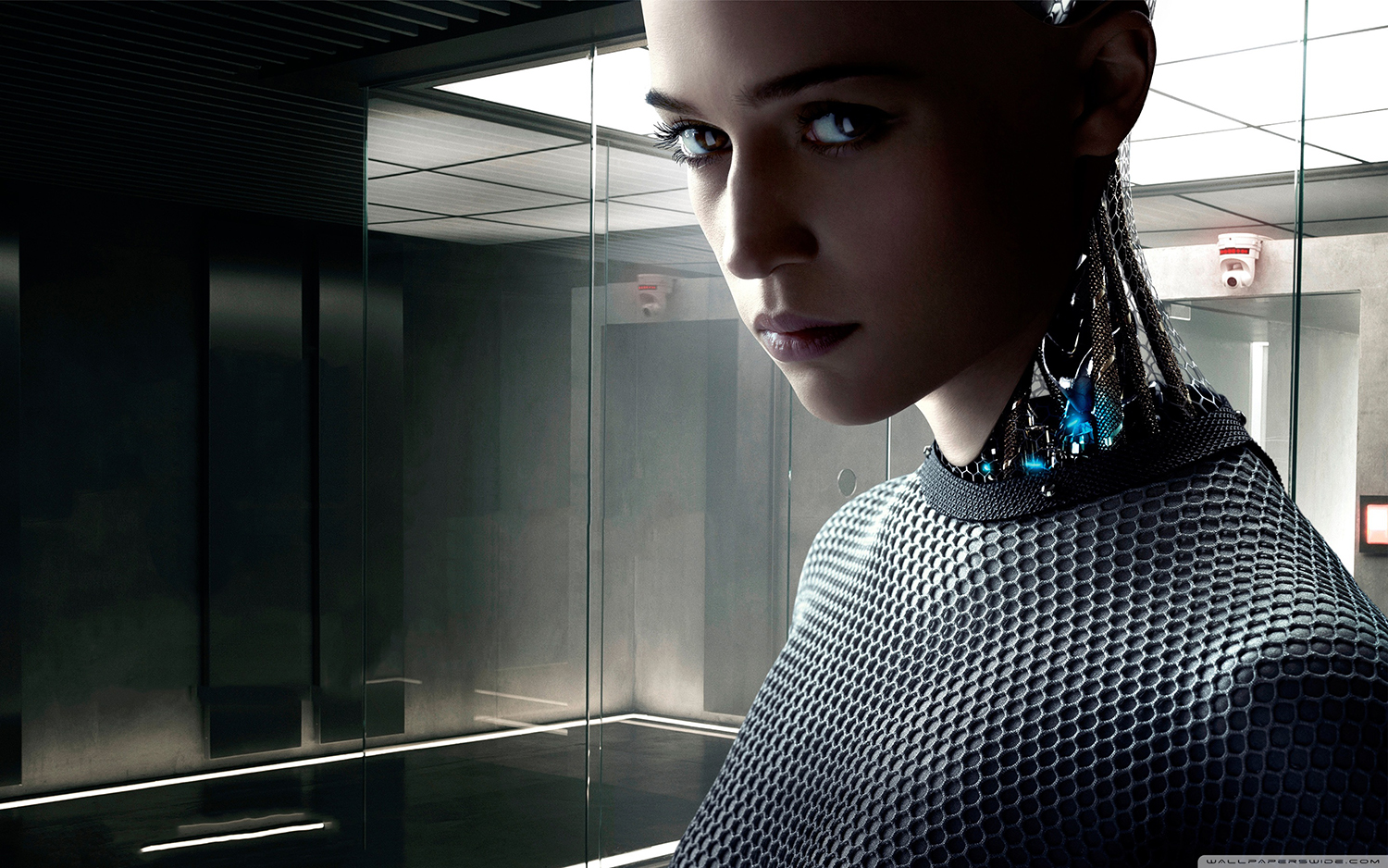

New approaches to message distribution mark a significant change in our engagement with digital forums. Algorithms construct independent environments that purport to reflect public discourse, but are in fact individualized products of a selection process that draws upon users’ personal details. Inside the echo chamber, privately held views appear as publicly accepted ideas, just as, by contrast, interest groups reduce a spectrum of public opinion to a single message. What is perceived as public gradually becomes private and vice versa. The ability of such algorithms to manipulate and interfere with democratic access to information and opinion is fundamentally disturbing. Concerns are perhaps driven less by a general rejection of modern programming than by the code’s covert functioning: abstract and hidden to the modern subject. The position of the modern self, wrapped within tailored, digital worlds, prompts questions about intelligent algorithms’ creeping entry into social interaction. Does the coder’s increasingly detailed spinning of data-based yarns create opaque worlds that dangerously advance mankind’s self-alienation? And do intelligent algorithms shield us from reality or instead present us with a mirror of humanity’s inner desires, piercing through social pretense and censorship?

In light of the gradual uncovering of potent digital mechanisms influencing the election process, MoMA’s PS1 has curated a timely exhibition tackling the relationship between art and coding. The show features Ian Cheng’s (b. 1984, US) trilogy Emissaries (2015–17), a series of computer-generated simulations conceived by Cheng over the last three years –– strange and complex worlds inhabited by wildlife, abstract geometric forms and oddly skewed characters that continuously interact, merge and transform. Emissaries comprises three interconnected episodes, each relating to a specific aspect of the cognitive evolution of man and machine, set in imagined past and future worlds gradually taken over by artificial intelligence. These dynamic ecosystems, described by the artist as “imitations of reality’s complexity,” are projected on wide screens that allow the viewer full immersion in their captivating sequences. Yet the stream of images and transmutations follows no discernible logic or pattern. The difficulties in describing Cheng’s digital worlds are fundamental to the work, with the artist using a video game development engine to define the basic parameters and values of the simulation. Subsequently, a set of specifically programmed algorithms independently shuffles and reorganizes these elements via a quasi-evolutionary process, creating an infinite flow of new combinations and rendering Emissaries a series of projections of the algorithms’ own artificial creativity.

A Japanese Shiba Inu dog is one of the most prominent motifs in Cheng’s simulations. This vulpine Shiba, often equipped with a hovering and detached leash, occupies the role of a companion, guiding the audience through the simulations. Cheng has previously advanced the idea of the human spectator as merely a visitor to digital worlds; in his 2016 show at the Migros Museum in Zurich, visitors would follow a projected Shiba using an interactive tablet. In a selection of short texts published in the exhibition catalogue, Cheng included a passage by Hayao Miyazaki in which the Japanese animation director describes how he envisions his settings as natural environments unspoiled by human intervention, and thereby representing a more fluid and ambiguous space, “freed from existing common sense.” Cheng similarly draws on this notion of fluidity by employing algorithms to continuously build environments that resist the implication of human authorship. The captivating spectacle of Emissaries’ ever-transforming setting similarly unsettles the established triangle of artist, artwork and audience.

Attempting to rationalize these random acts of creation within the algorithms’ neural networks is a futile endeavor. Their generated simulations are nonlinear and antiteleological in that their only purpose is to play through their own innumerable varieties. This deployment of algorithms to construct an infinite game recalls experiments in the evolving field of AI research, as developers have tried to design learning systems that would allow machines to learn how to play rudimentarily structured games independently. Recent research has revealed intelligent algorithms capable of teaching themselves how to complete a game as well as how to use their acquired knowledge to play other games. Cheng’s simulations run in parallel with these scientific breakthroughs. While Emissaries’ algorithms are not capable of organizing independent and cumulative thought activities, they open up an analogue realm devised and exclusively occupied by codes.

Defying human authorship, the creative labor of intelligent algorithms constitutes a dimension that is novel to art practice. The artist’s strategic deployment of codes suspends what French philosopher Bruno Latour has described as the “old constitution’s convulsive division of nature and society.” Latour contests modernism’s strict separation of subject and object and introduces the idea of a network of interactive, multilayered relations between humans, machines and nature. Certain objects in this network, termed “hybrids” by Latour, develop a life of their own and begin to affect the actions, thoughts and habits of the society that surrounds them. As technology increasingly enmeshes itself into society, these hybrids function as stabilizing bonds that, much like religious totems or monstrances, join the subject to the world. Emissaries functions as just such a hybrid, disrupting the division between culture and technology. The algorithm mediates between the artist and his audience in a way reflective of a broader social transformation triggered by the advent of AI. Returning to the self-directed algorithms of the presidential election, there is a similarity in the way both Trump and Cheng’s hybrids create a reality-distorting experience. In both instances, algorithms invade the public sphere and blur boundaries between science, politics and art. They signal an expansion of the social to the technological and a reformulation of society that consists of human and nonhuman members.

The virtual worlds of Emissaries enable visitors to explore a new and unfamiliar dimension, freed from ideological projections and cleaving the utopian/dystopian binary. In this fragile and volatile location, environments collapse, dissolve and cohere anew in a mesmerizing feedback loop. Artificial intelligence and the interest in immersive and intricate coding in contemporary art are here to stay. Whether intelligent algorithms signal salvation or the final dissolution of the world we know remains to be seen. Cheng’s Emissaries set their audience on a hunt for the underlying significance of the new virtual reality, only to find said reality broken free from its normative leash, romping around on four legs.