OK, OK, so good-time summer isn’t entirely gone; it probably never really is. Sounds a little true and somewhat right at least. Maybe there is even proof; this very instant seems cute and warm in São Paulo. So many faces we make out with, and others, having stayed home, remain in touch, always. I’ll say it again: the main issue with the idea of diaspora is the general misconception that people own or belong to a certain territory. When in fact, and historically, most people move the fuck around a lot. We could always end up in Brazil. Let’s go to São Paulo then, we said. In spite of bad timing — after all, 2014 has been, emotionally and existentially, like boarding an infinite roller coaster while high on meth. This year, again, there was endless twitter about separation and emancipation. Neither nations, institutions or even BFFs were immune to such ideas of dissociation. In between the demise of Sony Pictures and the slaughter of hundreds of children, Renée Zellweger and others kept growing up. The cyclic shift and eclipse not only changed individual faces but also (those of) social constellations. As always, some babies seem lucky to be born, while relationships are warily negotiated. Lineages are simultaneously claimed and obscured. Why so emotional? What does your horoscope say? Everyone is suffering because of something. Everybody can’t be happy at the same time. Besides these established and some upcoming facts, this text will attempt to guard its deceptive qualities. As every bleached-hair teenager knows, you can’t snake your way through life, coaxing yourself to your personalized apple, without shedding and re-growing your skin every so often. Shifting those identities incessantly. We’re pretty much the same people, we tell our pretty-petty selves, who we used to be before we exited that airport, coated in a Western delusion of grandeur seldom mistaken for glibness. UBER drivers only speak Portuguese. Yes, we ordered plenty of UBER cars. No, we don’t give a shit about your moral high ground.

The first steps played tricks on us, this initial yellow-green Brazilian instant, wrapping us in this really cute and warm feeling. For starters, this unpacks our very own cake of make-believe, actually thinking we’d be able to grasp a certain feel for this enormous place on the very first day. Is it possible? Maybe? Like glancing at a Breughel and instantaneously getting it? Being able to make out a larger picture from the tiniest details and the other way around. The sensation stays, until we spot the first rodent-sized cockroach and freak out like the cliché of a hysterical housewife, which we sometimes pretend to be.

My editor and I hang out in a penthouse-like apartment. Way too high for insects, phew. A local collector owns it; graciously he lent it to my editor. International artists Ken Okiishi and Nick Mauss apparently enjoyed their stay here too. There’s a turned-off TV in every room, probably for video art. The attempt to write a diary from and about São Paulo, as smug as that sounds, is in itself a pretty naive operation. How did Marco Polo sum up an empire? How do we paint a picture of a megalopolis, as vast and anonymous as São Paulo, in seven days? Especially when some attribute to this city a lack of images. This idea can be related to and derived from various cultural phenomena such as the history of concrete poetry and abstraction or the deep-rooted traditions of conceptualism in Brazilian art, as well as the ubiquitous pixação, a native mural-writing style, and the ban of public advertisement. Let’s quote our favorite longtime leftist polemicist, Adbusters, on the latter: “In 2007, the world’s fourth-largest metropolis and Brazil’s most important city, São Paulo, became the first city outside of the communist world to put into effect a radical, near-complete ban on outdoor advertising. Known on one hand for being the country’s slick commercial capital and on the other for its extreme gang violence and crushing poverty, São Paulo’s ‘Lei Cidade Limpa’ or Clean City Law was an unexpected success, owing largely to the singular determination of the city’s conservative mayor, Gilberto Kassab.” Let’s quote him too: “The Clean City Law came from a necessity to combat pollution… pollution of water, sound, air and the visual. We decided that we should start combating pollution with the most conspicuous sector — visual pollution.” Simply seeing photos of São Paulo, it’s amazing to see this sprawling metropolis completely emptied of signage, completely emptied of logos and bright light. Before, apparently, you couldn’t even make out the architecture of the old buildings, because all the buildings, all the houses were just covered with billboards and logos and propaganda. And there was no criteria.

The subsequent city of São Paulo is anonymous and vast. Not only in itself but in comparison to the other big places in our world, São Paulo seems less sophomoric; there is no signifier working as a symbolic stand-in for the city. São Paulo merely represents itself, in its totality. It’s too much information for one representative image. And this, precisely, is it — as contemporary as an urban experience can get these days. A place that condenses the largest industrialized metropolitan area in Latin America, probably over twenty million people, a massive, shiny blob seen from space.

Its close neighbor, Rio de Janeiro, famed for it’s beaches, Carnival and Jesus, might be beautiful but in comparison remains provincial and post-colonial. São Paulo, on the other hand, feels like it continuously manifests as its own consequent future: with all its heavens and abysms, with all the flavors of last-century modernism gone next-gen millennium. As if the notion of modern life wasn’t challenged, surpassed and deconstructed, as happened in the U.S. and Europe. On the contrary, a rather cocooned version of modernism — having slumbered through decades of authoritarian regimes, dictatorships, corruption and violence — has metamorphosed into its own distinct mixture of contemporary capitalism and culture. No pretend paradise, but a very individual and unique home for a myriad of human beings and activities to say the least.

According to the World Health Organization, the murder rate in São Paulo is classified as “epidemic,” even though it has seen a decline by a remarkable two-thirds in just over a decade. You care too much about numbers, says my editor. Well, I do. He sighs. I light a cigarette and together we gaze through the penthouse windows. In every direction we marvel at the vertical city. An often-used example for the massive social divide in São Paulo tells of the ultra-rich chartering helicopters like a New Yorker hails cabs. The overlords never touching the ground of their city. Sounds like semi-gods riding dragons in an alternative fantasy scenario. Supposedly there are so many helicopters, they can’t use their radios and have to navigate by eye. We scan the sky for flying taxis but can’t spot any. Maybe this relates to the fact that recently some of São Paulo’s one percent has been arrested. The national oil company Petrobras was basically unmasked as a private equity. The Economist says: “Not long ago Petrobras was the pride of Brazil. It was steward of the biggest offshore oil discovery so far this century and the subject of a record-breaking $70-billion public share offering in 2010. It had become the technological leader among oil giants at finding new reserves. But now the state-controlled behemoth is sinking into a hole as fathomless as its deep-sea oil wells. Every day brings news that ranges from bad to dreadful, much of it the result of a 10 billion reais ($3.7 billion) bribery scheme that was recently unearthed by Brazil’s federal police, aided by the press.” A pop-up ad by Shell, a Petrobras competitor, allows some perspective on the international high-stakes oil game. This can’t be merely a Brazilian mess; too many heavy players are involved in this game. Another article by The Economist says: “According to revelations published in Veja, a leading weekly, and Estado de São Paulo, a newspaper, Mr Costa, who ran Petrobras’s refining division from 2004 to 2012, has accused more than forty politicians of involvement in a vast kickback scheme. The list reportedly includes a minister, three state governors, six senators and dozens of congressmen from President Dilma Rousseff’s Workers’ Party (PT) and several coalition allies. The beneficiaries are alleged to have pocketed three percent of the value of contracts signed with Petrobras in return for supporting the government in congressional votes.” I leave the penthouse and take an UBER to the house of my hosts. Upon arrival, immediately lost in translation, the doorman — almost every edificio (apartment building) is equipped with one — won’t let me in. A bit lost, I whatsapp: Yo, Francesco, I’m downstairs and I can’t get in. He picks me up. My hosts are two very handsome young Italian men (Francesco and Luca). They grew up together and they both recently set up contemporary art galleries in São Paulo (Boatos Fine Arts and WARM). They’re both straight and they sleep in one bed. Back on the street, I chat with a curator friend who’s part of the residency program Capacete in Rio de Janeiro. She’s five car hours or one plane hour away.

Are there streetlights for pedestrians in Rio? Yes. Aren’t there any in SP?

It’s my first day. But apparently there are almost none.

How do people cross? They run.

Perambulating the local neighborhoods and art scenes the next days. The initial areas of the city, which we are pointed to, are entirely posh. Luscious tropical gardens, fencing around hidden palaces. They don’t seem that pompous, but each of these residencies remains secluded, guarded behind electric barbed wire and segregated from the unknown masses living downtown. Most brown-skinned people, I see in these parts, are guarding houses, black valets or security guards in ironed shirts or uniforms in front of one of the dozens of expensive furniture galleries and other semi-artisanal, super-cheesy design shops. The very few art galleries are mapped out quickly. The local Kunsthalle, run by Swiss-educated Marina Coelho, predominantly showed Swiss artists such as Vanessa Safavi or Tobias Kaspar this year. There are a number of other independent exhibition spaces. Like Pivo, housed in the Edificio Copan, Niemeyer’s praised wavy building, mimicking the female form. Was it inspired by the curves of an actual woman? Fernanda Brenner, artistic director, gives us a tour of the current exhibition by Regina Parra, “é possível, mas não agora” [It’s possible, but not now]. 7.536 Passos (Por uma Geografia da Proximidade) [7,536 Steps (For a Geography of Proximity)] is a twenty-minute-long video work that Parra made in 2013. It shows a POV-walk from downtown to the Bolivian neighborhood in São Paulo. According to estimates of the National Association of Immigrants from Brazil, more than 200,000 Bolivians are working illegally in São Paulo. On her stroll through the city, the artist carried a portable radio, capturing pirate radio stations. The film is colored in a yellow-brownish hue. Weirdly enough, it resembles more the image of an exotic Brazil, which we thought to know before we ever came here. An image that doesn’t resemble the actual experience of the city. It doesn’t really seem that exotic after all. In this sense, the work considers the idea of proximity in more than one way. The topics and issues portrayed in this work might seem closer to us than they appear.

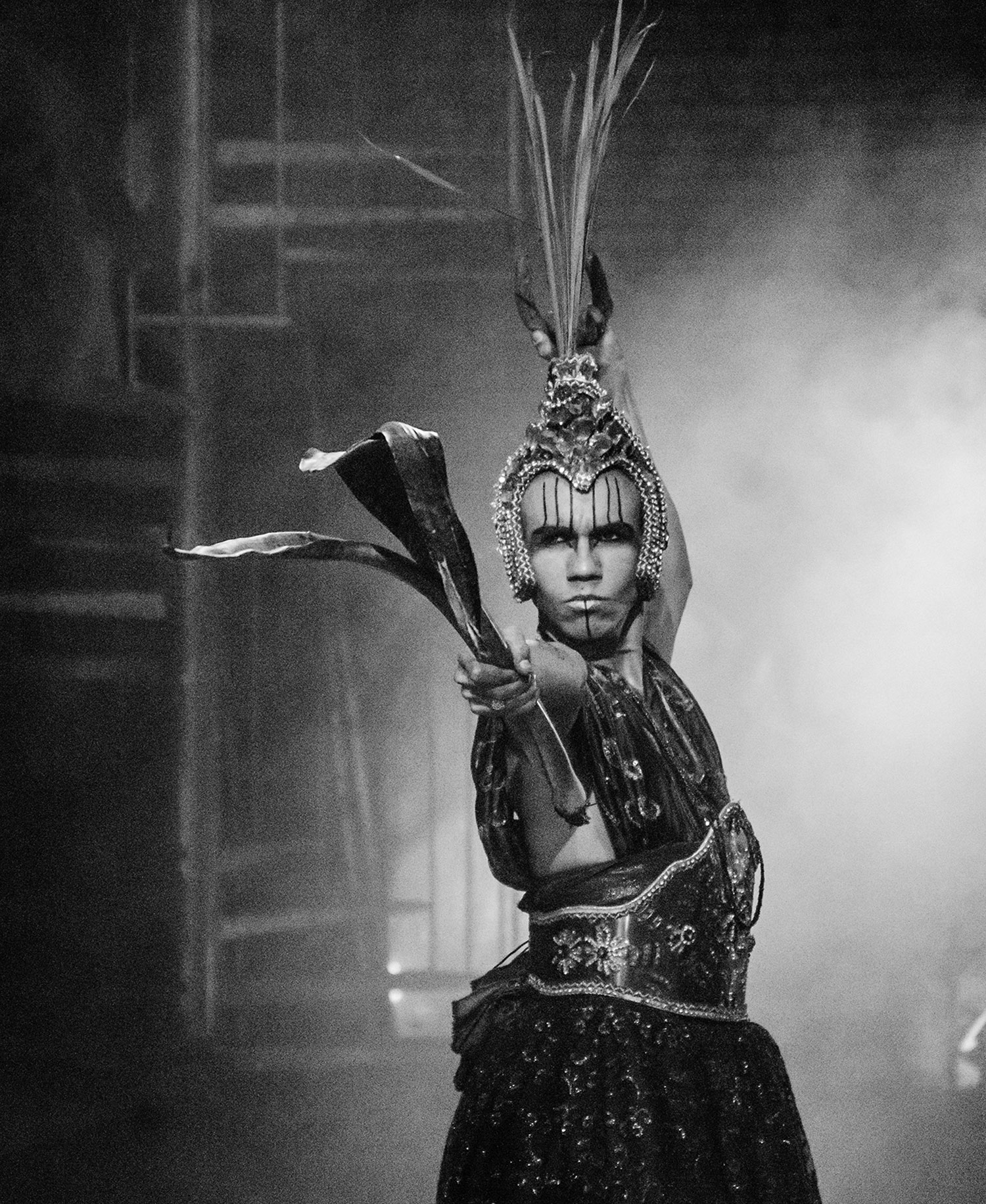

Why does this area of the city, referred to as downtown, the supposed danger-area, attract us so much more? Hide your smartphone when you walk around here, advises Francesco. You’ll get mugged. Yusuf Etiman, a German-Turkish artist, who programmed the infamous Basso in Berlin, has been coming to São Paulo a lot. First I came in 2009, he says. Now it must be my thirteenth visit. Between 2011–2012 he rented an apartment and spent maybe seven months in this city. He wants to move back now. He takes us to a bar, behind the Edificio Copan. He orders rounds of fresh watermelon and lime juice for us. They taste so amazing, I don’t want it to end. His Portuguese is excellent. At this point, my editor turns around and says, they are quite picturesque, the people here. This reminds me of wall writings I had seen somewhere in the city. There is no music without rhythm. It’s the tact, I think, that dictates most relationships. Not only human relationships but also the relationships between objects. I ask about the engraved writing in the mirrors in the bar. Apparently they say: Look here, this isn’t working for us. I ask Yusuf about Rio de Janeiro. “It is like another country,” he says. “It’s nice to be there, but I’m so obsessed with São Paulo, Rio just can’t compete.” But the juices taste even better in Rio de Janeiro, he admits drily. Tobi Maier, a German curator, living here for years, considers Yusuf Etiman to be an important Brazilian artist. “But what does he do?” “Performances. Not rarely in the streets.” We admire the colorful geometric tiles by Antônio Maluf, which are placed not symmetrically but in a disrupted, off-beat way all over the bar. “The true Brazilian avant-garde though,” says Maier, smilingly, “is in theater.” My editor sighs again. Let’s do it anyways. And we’re lucky: besides a display of an impressive wall of photocopied body parts by the late and amazing Hudinilson Jr., the current issue of the São Paulo Biennale offers a theater event in its program. Every Friday and Saturday across from the municipal theater (which puts on Othello for more bougie audiences), inside a defunct subway station, you can see a play by the theater company Teatro da Vertigem. The audience is guided behind the vitrines that flank the corridor. The glass of the windows is covered in mirrored foil. In the different lighting they switch on and off, we are able to see either the corridor, the audience sitting across from us or ourselves. Two TV screens mounted on the ceiling allow us to observe the entrance and the exit of the underground pathway. The entire play consists of actors walking past us, performing mainly without dialogue, wearing various costumes. In addition to the actors, they direct pedestrians from the streets past us as well. This is the main effect of the play, allowing the audience to indulge in the voyeurism of the common passerby. The lines between who is part of the play and where the fiction begins and ends are blurred beautifully and mainly in a very natural manner. A recurring motif is the anticipation and execution of violence: from an actor playing a political activist, who threatens to throw a stone at the window in front of the audience, to the random incident of someone brutally punching the inside of a baby stroller, this effectively builds a level of suspense throughout the whole play. In the end one of the exhausted actors enters the space behind the window, past the audience, until he stops right in front of me. While he is getting undressed to his Speedo, his sweat keeps dripping from his hairy back onto me. His body smells as if he had just showered. As we leave the theater, a beggar-child comes walking directly at us. Before he can say anything, my editor offers him a can of Coca-Cola, which he was just drinking out of. The kid grabs the can and keeps walking without a word. The speed and speechlessness of this interaction mirrors the experience of the performance we had just witnessed.

That same night, we hang out at the beautiful home of two local gallery owners. German-Polish artist Maria Loboda, who’s preparing the upcoming show in one of their venues, comes over. Fernanda Brenner and other people from the local art scene drop by as well. There is an emergent population of young, English-fluent, technology-literate, upbeat art professionals who don’t feel the pressure to leave the country but internalize the ambitions of their U.S. and European counterparts by offering alternative yet inspired program and projects.

Later we go to a nightclub, inhabited by topless bears, ripped to perfection and cloned out of control, many high on GHB, rubbing their slickly shaved skins against us. None of these men seem to have identity issues. Pedro Wirz, Swiss-Brazilian artist, accompanies us home for a nightcap. Speaking to him, I realize our arrogance in matters of art, how we travel the world with a predetermined set of criteria. Criteria about anything from aesthetics to our idea of how to work in this field of ours. This arrogance is maybe important to make sense of the innumerable trends and ideas within contemporary art. But I realize that the criteria about what is good and what is not stem from a mixture of supposed knowledge about the state of things, which allows us to define our own position. This supposed knowledge sounds like a grounded basis for said arrogance but it is in fact a most unstable one. Since our opinions about what to believe do get turned over radically and not rarely by surprise. The arrogance stems from experience, which seems to be an authentic source but also hard to prove because it remains utterly subjective in the end. Which makes it hard to believe anything. The last and in my opining least interesting but usually most strongly articulated source of said arrogance is taste. Which can, as we all know, change upon deep reflection. Pedro Wirz has initiated Postcodes, a tool to produce exhibitions and other forms of exchange between local and international artists in São Paulo. In a recent show, he invited Swiss artist Kaspar Müller to participate. On my way to the airport, I remember that before I came to Brazil, I had spoken to Kaspar about his experience in São Paulo. Not as much as when I went to Trinidad, he said. But I went to São Paulo and learned a lot too. The world, ultimately, I think, isn’t as strange, as it always has been ours to experience. Unbreak my heart, sings Toni Braxton from the radio, as my UBER takes the lane to Terminal 3 at Guarulhos International Airport.