Flood-tide below me! I see you face to face!

Clouds of the west — sun there half an hour high — I see

you also face to face.

Crowds of men and women attired in the usual costumes,

how curious you are to me!

— Walt Whitman, Crossing Brooklyn Ferry1

As I acclimated to the wind-blasted cacophony that soundtracks Anna Rubin’s video The Gram (2024), all I could see was water. It jumped around the modest flat-screen monitor mounted to the wall of Maxwell Graham’s gallery in New York. Rotting pilings and jetties and maritime detritus ricocheted around the frame and the sun was reflected in the chop. The noise was so dominant, and the image so unsteady, that I lost my understanding of how this could have been made. I was reminded as I re-read the spare exhibition text that Rubin’s camera operator was a homing pigeon, documenting a journey from Midtown Manhattan to its roost in the Bronx with a tiny spy camera. I was joining the bird about halfway through her trip as she flew over the East River.

This is a story that is best received from the beginning, when the bird lurches skyward in a pedestrian plaza dotted with umbrellas, bistro tables, and large concrete pavers to protect civilians from the threat of traffic. A swirl of crosswalks gives way to rooftops and their accessories: whirring fans, water tanks, gardens. Roofs are one of the few places in the city where things “can go.” It is fitting, then, that four minutes into its journey, as the bird circles above Kips Bay and Murray Hill (Hello, Kips Bay Towers! Hello, Tudor City! Hello, NYU Langone Medical Center!), it finds a place to perch atop a towering condominium. High up, the city is quiet, and this pause in the action emphasizes the stamina of the messenger. The camera captures an unexplainable urban assemblage of thick metal wire, rope, and a satellite dish — beyond it, the skyline. I find myself grateful to Rubin for entrusting the recording of this video to a nimbler proxy who can provide us with views we otherwise may never see. There lies a certitude in this exchange between Rubin and the bird, one that encapsulates an entire history of pre-digital communication systems in which human words and images were entrusted to animals with senses that far surpassed our own. Yet the work is playful with histories of moving image, of messaging, and of cities. It is wistful and hardcore. Cities find rhythm through tides of loss and the constant slippage of both individual and collective memories. A gleeful Rubin wads up time and throws it in the bin again and again.

As the bird resumes its trip home, the camera captures a bracing plunge from the edge of the building that is halted by flight. The remaining footage maps, among other things, the strange ways in which the city constructs itself around its waterways. Athletic fields and promenades appear and disappear, interspersed with industrial expanses and parking lots. Soon, homes reappear, closer to the ground. In a slapstick denouement, the bird glides onto her handler’s roof and click- clacks her way to the edge, catching her reflection in hot gutter water. Her shaded roost, flanked with exercise equipment for humans, enters the frame and the video ends. In total, the trip lasts around twenty-six minutes, just a few minutes longer than an episode of 30 Rock (2006–2013).

Rubin’s bird carries no message, but rather authors one through flight. The resulting document is slippery, and, though it is shot in a single take, foregrounds the psychedelic, staccato energy of flicker films, most potently captured in Tony Conrad’s 1966 masterpiece The Flicker. But Rubin’s gone digital, and the flicker is more of a flap. Using animal movement as a primary visual driver, The Gram feels more indebted to late nineteenth-century film explorations in which magic lies in pure movement, that what we see also lives. “Cinema brought the edge of actuality, the warrant of the present, the claim that ‘this is,’” writes Annette Michelson, who delves into the relationship between moving image and vivacity alongside readings of early cinema and structuralist film in her 1989 essay “The Art of Moving Shadows.” But what happens when a still image interrupts? She expands, “For to watch a film move between freeze frame and motion is to live cinema’s generative moment, its opening of a paradigm shift.”2 Rubin sends this assertion into overdrive. Propelled by the bird’s jerky capture of footage, what is this video if not a relentless succession of freeze-frames? The Gram is stop-motion, gravity-defiant bodycam footage. Existing in this uncommon territory, Rubin seems less concerned with cinematic grandeur and more interested in the thrill of instability.

The video is buoyed by a sense of wonder, a sentiment shared by those who first encountered aerial documents taken by pigeons in the years preceding World War I. But today, image-making is a bastardized pursuit, and pure filmic wonder had a good, century- long run. Rubin is not precious about this and instead embraces the cheap ubiquity of contemporary camerawork, suspending it hundreds of feet above our heads as lo-fi spectacle. What we see can be impressive and shitty at the same time. Viva New York!

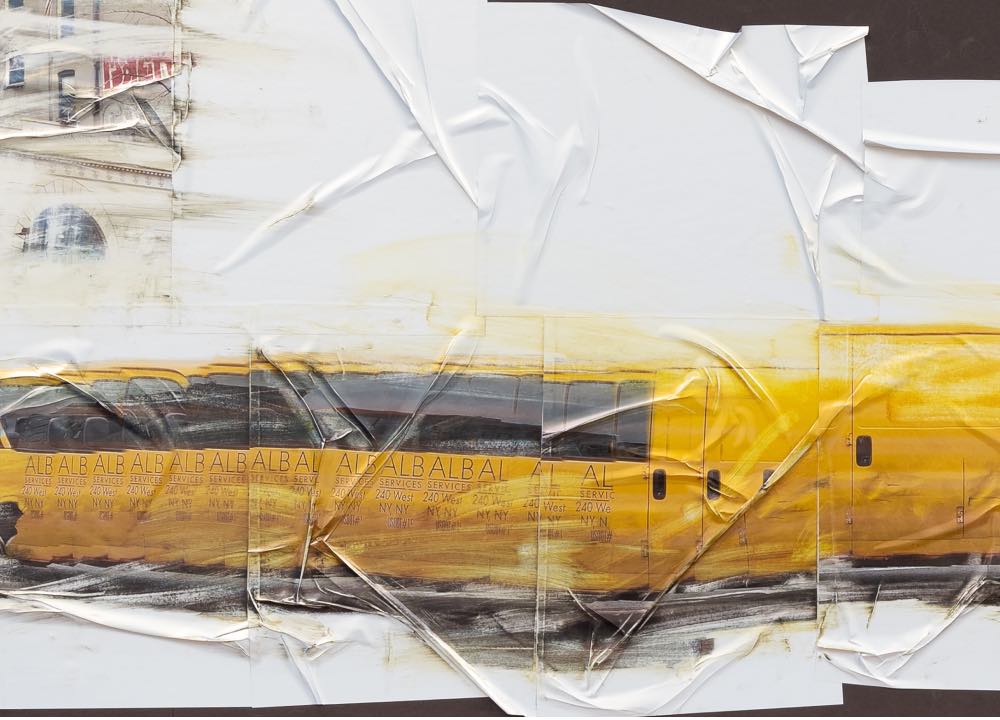

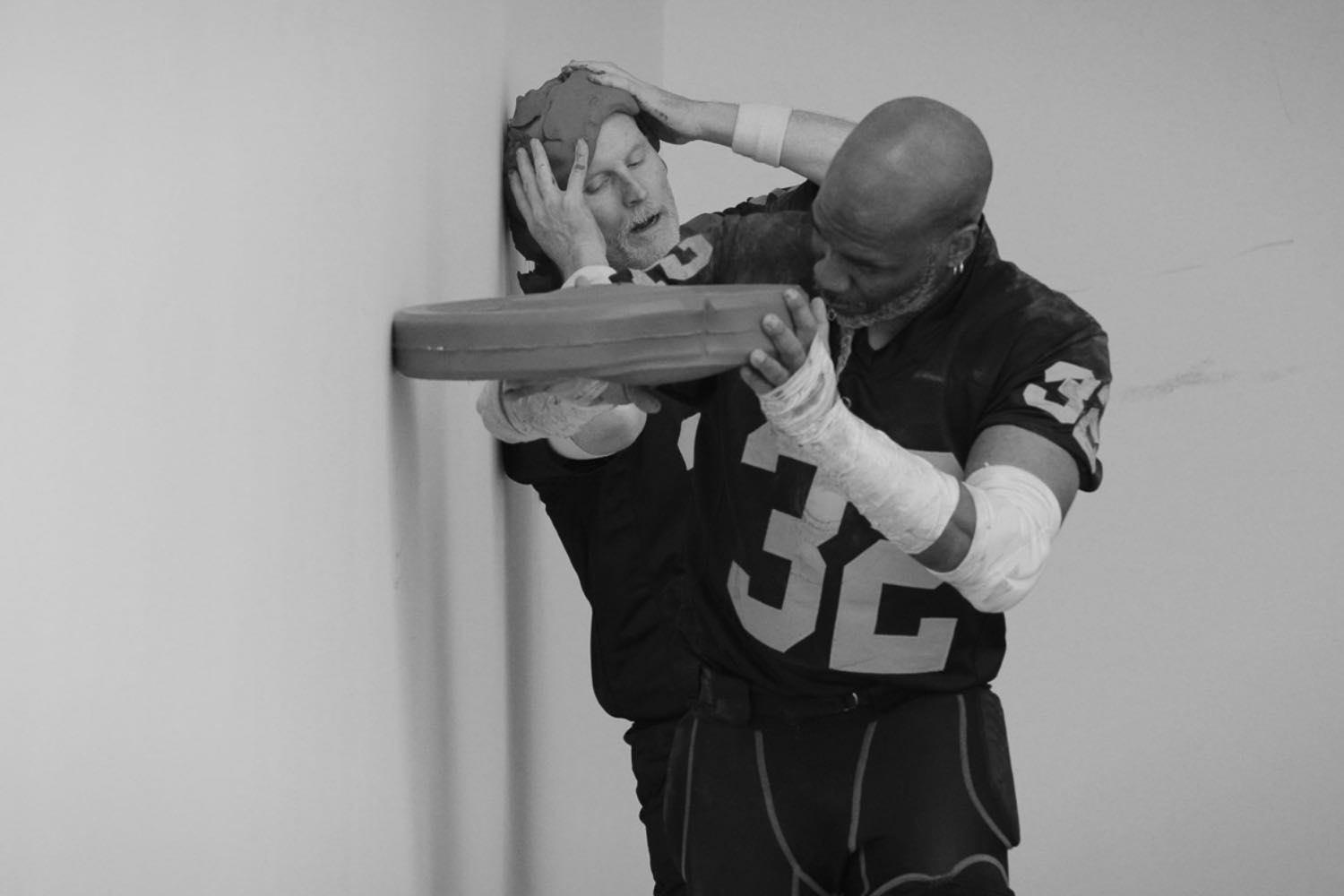

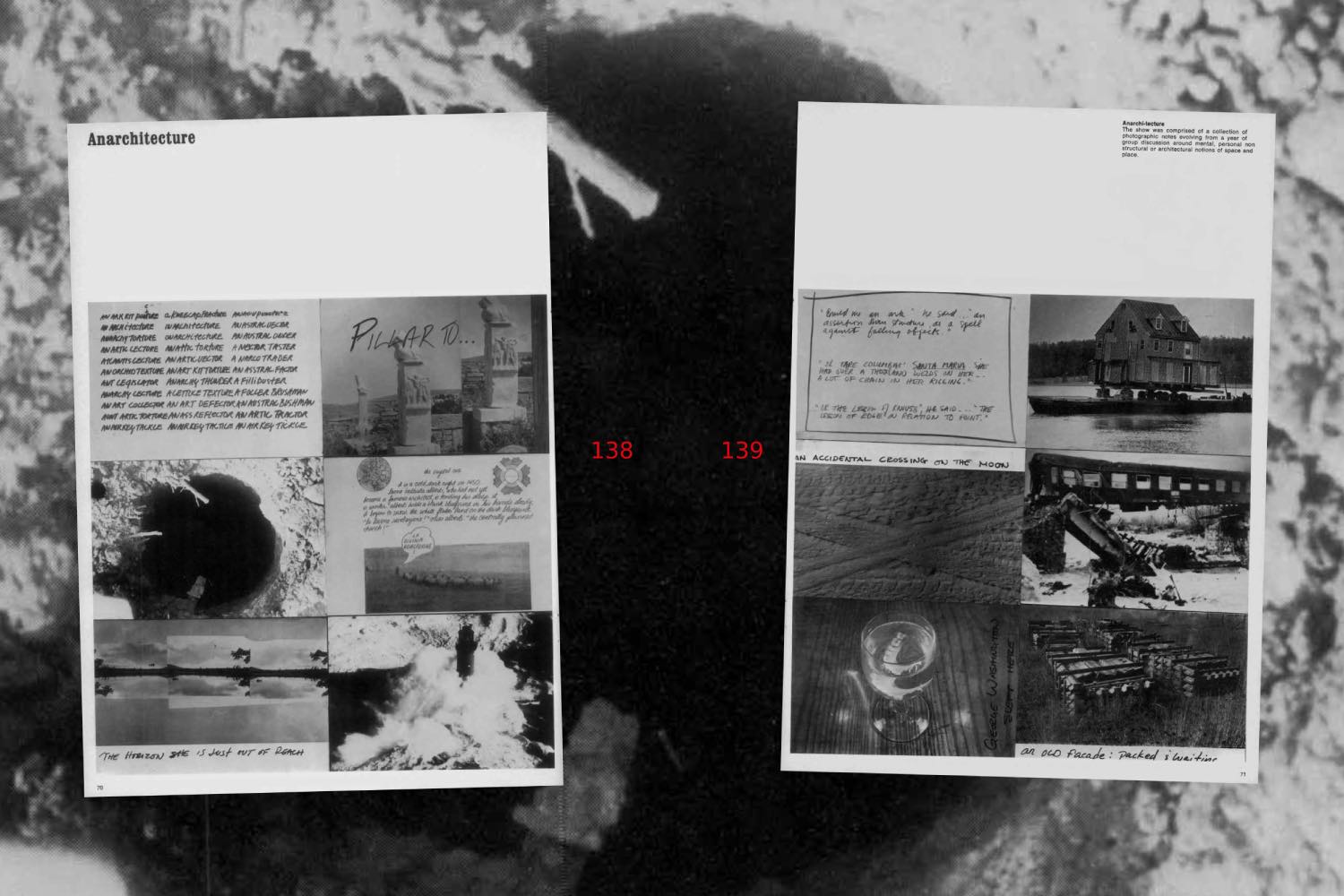

I don’t know much about Anna Rubin, but I do know that she is a native New Yorker. Win McCarthy is too. His exhibition “Kingdom Come” (2024) was on view at Francis Irv, concurrent with Rubin’s show at Maxwell Graham. The religious bent of the show’s title finds kinship with the chaotic omniscience of Rubin’s video, which, in its incessant darting, adopts the vision of a biblically accurate angel. But McCarthy foregrounds a noble tension between one’s individual and collective experience of New York. Human beings, not animals, are centered in this presentation. Across the gallery unfolds a skeletal depiction of a street most clearly distinguished by the inclusion of printed images of Fleur du Mal perfume advertisements on construction sheds. Folded fabric (protected by plastic, evincing some gentle care), masonry bricks, and stacked plastic containers labeled with language (10 minutes, daughter, red, permanent stain) add to the scene. These are vessels for time, sentiment, and responsibility, but they also hold nails and paint and leftovers. It’s the double duty that essentializes life in New York. Being just one thing is a luxury few can afford. McCarthy’s sculptural invocations of streets under construction are surrounded by mosaiced panoramas of city life, shot on an iPhone and pasted together with a slapdash flair that evokes wheatpasted posters on temporary constructions. There is a steep stairwell of a walkup, a hyperextended delivery van dragged in opposite directions, and a vertically inverted intersection featuring Anish Kapoor’s bean sculpture wedged into the entrance of 56 Leonard Street, not far from the gallery where the work was on view.

McCarthy’s photographs wrestle with legibility, and ultimately culminate in something recognizable, but there is both pleasure and confusion in their painterly fragmentation. The vertigo- inducing quality of these works plays with the vulnerabilities of ubiquitous image capture, and how easy it is for an individual to mimic and deflate these all-seeing technologies just by standing on the corner. Within the documentation of McCarthy’s exhibition is a photograph taken from the window of the gallery, overlooking a nearby construction site. There is no art in the image, but just below the hulking pile of rubble is a small SUV with a camera mounted on the roof. There is something so flimsy and pathetic about this assemblage, as though the car is wearing a baseball cap with a propeller on top. Inching through traffic, it is a foot soldier in the essential mapping of our existence.

Both Rubin and McCarthy made shows with tools you can hold in your hand, that accompany your walks around town. The resulting artworks are delirious: stretched, dirtied, loud. There’s a comedy to the overextension that choreographs life in New York, and these are artists with a sense of humor. In the mid-1990s, when Rubin and McCarthy were young, Friedrich Kittler wrote that “technical media have miniaturized the city to the precise extent that they have also made it expand toward the entropy of the megalopolis.”3 When the city collapses to fit in your pocket, your relationship to it can get messy. In the summer leading up to these two shows, Dora Budor’s video Lifelike (2024) was on view in the 2024 Whitney Biennial, “Even Better Than the Real Thing.” The massive concrete blocks that provided seating for visitors at the Whitney could be seen in the early seconds of Rubin’s video, in the pedestrian plaza where the bird takes flight. While Rubin covers the east side of Manhattan and the Bronx, and McCarthy covers downtown, in Lifelike Budor trains her camera on the shopping-mall-cum-neighborhood Hudson Yards.

Budor films with an iPhone mounted to a gimbal and pulsating pleasure devices, creating a visual that is blurred and carnal, like the footage is doing body rolls for us. The scenes are mundane and show passing cars, revolving doors, people walking, but the sheen and menace of new construction emerges through the vibrations. Amid the high rises, protected walkways, public artworks (Charles Ray’s Adam and Eve, 2023, the original sinners all grown up), and the existential architectural quagmire known as Vessel, Budor posits that we might be getting fucked. In a short descriptive text about the work, Budor invokes Sianne Ngai’s portmanteau stuplimity to describe the valley of feeling between thrill and boredom, pleasure and disinterest in contemporary life.

It is an apt descriptor for Budor’s recent video work, but also the art of Rubin and McCarthy, who are both using everyday means of image capture to grapple with how estranged one can become from what they think they know. The street, which courses through all of this work, provides a familiarity to control abstraction and navigate and play with this unease.

I don’t live in New York anymore. I missed the April 5th earthquake. The city was a microcosmic America I knew well, and one that will always direct my psyche to some degree. I live in the Rocky Mountains now and throngs of people are a rarity, as are rumbling machines and hulking buildings. There’s a Whitmanesque joy in the observations of Rubin, McCarthy,and Budor, a celebration of the hallucinatory nature of New York, and a lack of sentimentality around its and our impermanence. A poem authored by McCarthy to accompany his show concludes with disarming directness:

Don’t say everywhere steel.

Everywhere glass.

You are here, around.

Everyone.

First breath, last breath.

Everywhere.

Dark, then light, then dark.

Same second, same pulsing second. Same hour. Everyone idiot. Beautiful, beaming idiot.

Stand. Sit.

Always return

Always rent free from then.

Always, occurring. Until never.

Never was. Never once. Not at all.

I left Rubin’s exhibition with the bird still flying, the strident sound of its motion fading as I ascended the stairs. As I turned the corner from the gallery onto Essex Street, walking along Seward Park, I felt self-conscious, aware of my humble station within the avian networks of New York City. The sky teemed with more life than I remembered. I felt subservient and watched, like a tourist.