![“反复 [FANFU],” installation view at Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2015) Courtesy of the Artist and Karma International, Zurich. Photography by Aurélien Mole](http://flash---art.com/app/uploads/2016/06/Melanie-Matranga_FlashArt.jpg)

These are the terms in which French philosopher Jean Baudrillard described the peculiar fragmentary style he used to write Cool Memories — a series of autonomous aphorisms forming a continuous reflection from 1980 to 2000. His commentary is quite relevant to Mélanie Matranga’s polymorphous practice: Starting from a multitude of banal objects, characters and situations, she builds up fragmentary environments, shaky and precarious moments that have, precisely, the consistency of an evanescent memory. “There are no rigid structures, nothing stands up properly,” she says, describing her work in an interview with curators and castillo/corrales members Thomas Boutoux and Benjamin Thorel. “It’s rather like a ghostly presence, or the residues of moments. But it all remains quite impersonal, with nothing very singular. Very banal objects. Things become jaded. These moments have no solidity — as in a memory, when you’re alone with other people.”

Born in 1985 in Marseille, Matranga developed a practice that spans drawing, sculpture, video and environmental installations, yet is paradoxically unified by a certain sense of cacophony and jamming: objects, cables, thoughts and dialogues are muddled, and speak quietly, through mundane gestures — smoking a cigarette, listening to music — about the very timely notion of “being together.” The daily, the casual, and the way these can be fixed within a form, fascinate Matranga. Her sculptures often start from a familiar shape —a bed, a Gameboy, a couch, a biscuit — that she either rigidifies with vinylic glue (see the exhibition “Issues of Our Times” at castillo/corrales, Paris, and Artists Space, New York, 2014) or else softens by casting in silicon — a material she qualifies as “sloppy and revolting.”

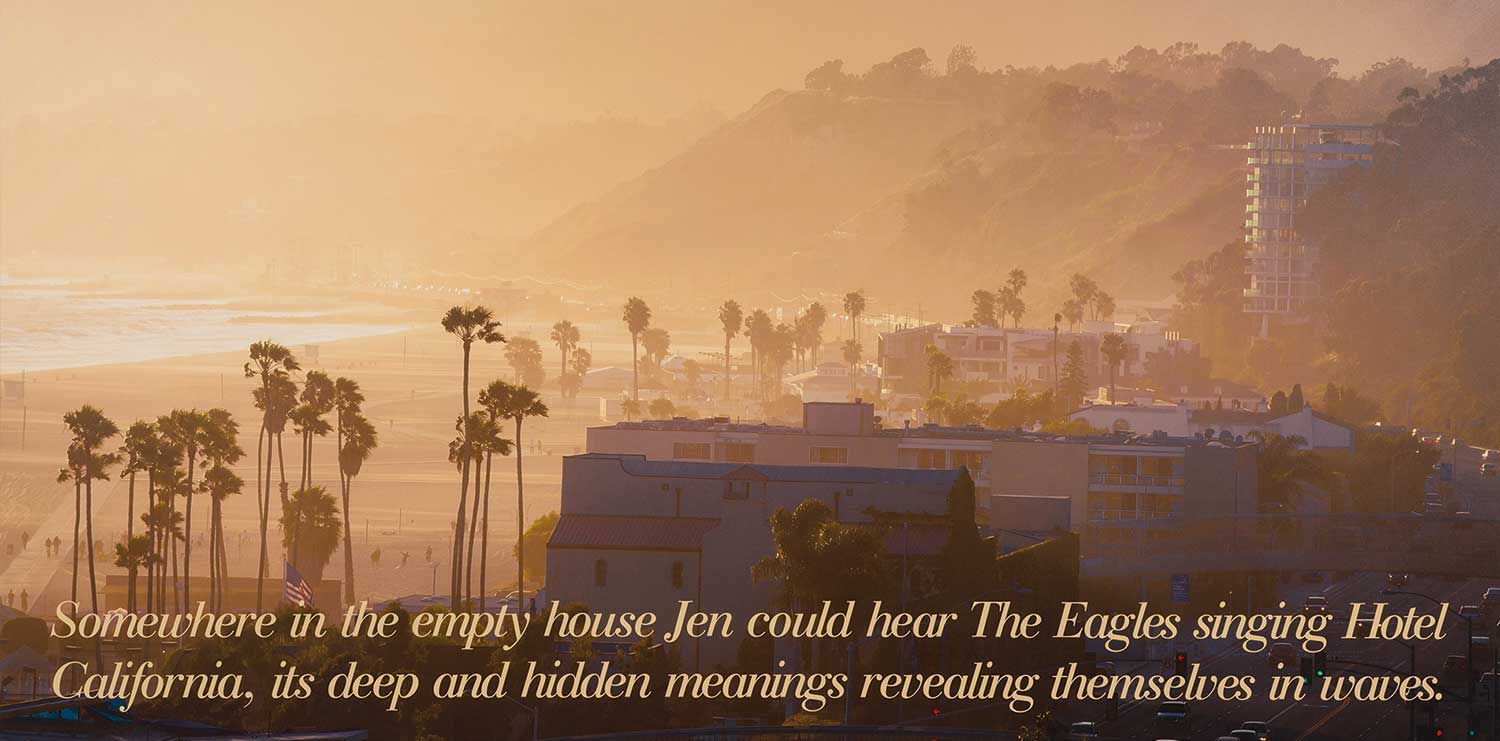

The form, a relief or counter-relief, is fixed within its triviality and stands for all the symbols that it bares. Objects don’t hold any singularity; they are truly generic: the Noguchi lamps populating the underground space of Palais de Tokyo, Paris, during the fall of 2015, for Matranga’s solo show “反复 [FANFU],” have been edited so many times that they refer to everything and to nothing at the same time and thus can be interpreted in a far more emotional way. The music blasting through the same space is very popular, very recognizable, referencing a period of time as well as a generational taste, yet remains quite nonspecific. Matranga disseminates artifacts and sounds that production and circulation have worn out until their very essence becomes trivial.

These are turned into impersonal codes or signs one uses to define a certain positioning within society — a “personality.” “When you’re alone,” she reflects in her interview with Boutoux and Thorel, “what’s your personality? What, in fact, does this term mean? The propositions I make, all these extremely common objects and simple situations, are hugely amplified: They’re there to be experienced simply, almost in a loop, and in a really artificial way.” The cast objects become ghostly and residual presences, testaments to a past moment as well as the setting for a new moment to be lived. Indeed, Matranga’s works shouldn’t be experienced individually but as a whole, as an environment; they demarcate an actual living space, playing on notions of both domesticity and public commodity, oscillating between a glue-coated inhospitality and a soft, comforting intimacy. The exhibition becomes a public space within the public space — of the gallery, of the museum — a space of cohabitation, a communal mental area where each individual, like each object, tries to find the right position.

Big family mattresses are scattered across the floors, smoking areas are arranged within the spaces, while everyday objects are randomly disseminated. Matranga’s compositions bring up a certain notion of self-affirmation through objects that connote the intimacy of shelter.

The tension she draws between individuality and community actually rehabilitates the visitor as a subject, as an ethereal presence within a space where both instantaneity and memory are required to go through a psychological experience full of potential. She deconstructs the syntax of the exhibition structure in the same way she might compose a suave melody. Or is it polyphony gone wrong intentionally?

By amplifying the mundane, Matranga creates hyperartificial situations that replicate the contrived structures of a given society: How can one exist among others? How can one be “alone with other people,” as she says? By giving space to the intimate and allowing singularities to blossom, Matranga creates situations that are saturated with emotion. For “Club,” her first solo exhibition at Édouard Montassut, Paris, in 2016, she covered the walls of the gallery with large fabrics — sheets, pieces of linen and silk, wool — on which generic, adolescent messages of love were embroidered over occasionally goofy backgrounds: LOVE, NEED WANT, FEELING, ALWAYS YOURS, YOU AND ME, LOVE LOVE LOVE, YOU AGAIN AGAIN, EVER EVER NO STOP. Here again, the words are so threadbare they don’t mean anything anymore, and yet they manage to convey this sense of collective intimacy that runs throughout the artist’s practice. The words, the objects, the music, the messy arrangements, the watermarked scrapbook aesthetic seem to draw the viewer into a teenage world, a moment of transition when feelings are out of control and emotions are stuttered — like silicon or glue dripping from a sculpture — before attaining a more mature elocution.

Matranga’s physical arrangements and visual compositions can often be seen as a mirror for the mind. This is, for example, how she describes Complexe ou Compliqué (2014), the installation of wires and cables entangled under a carpet that she showed in Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris, as well as at Artists Space, New York: “It was a way to create more organic spaces, which imitate sentiments or sensations in a rather exaggerated and sometimes even quite simplistic way. And then, it had an extremely loquacious side to it: For me, these cables and these dripping materials were just like logorrhea or chatter. Making these pieces meant using lots of words to say something simple, going via a million roundabout routes to arrive at a single point.For me, that’s what language typically is.”

The talkative forms that she gives space to in her installations find their counterpart in her video work as self-absorbed, chatty characters who seem, indeed, to be alone while being with others. Matranga’s films are more about narration than about any kind of formal speculation. She mixes scripted fiction with improvisation, giving her productions an ambiguous sense of intentionality and genre. Speech is omnipresent, yet its content doesn’t really matter. The succession of words is not important in itself, and the content is interesting only in its capacity to define the act of speaking, the postures, the bodies and their movements, the silences and the pauses. The words are interesting when they stop. Matranga revisits and challenges the conventions of oral exchange by fostering an intransitive speech. This is pretty clear in the project she realized on the occasion of her Frieze Artist Award commission: From A to B through E (2014) is a short web series about a young couple, Jeanne and Bastien, who discuss “freedom, success and the proper functioning of a couple” while a cafe set is built around them, suggesting a parallel logic of physical/emotional construction. The overall arc and direction swings between a constructed dialogue à la Eric Rohmer — characters entangled in their own problems, words scrambling the action’s progression — and a very contemporary kind of reality-show speak: empty, flat, self-centered. From the first minutes, Jeanne, the main character, interrupts her monologue with a very significant statement: “I was talking for ten minutes about something important to me and you were just not listening to me? Are you fucking kidding me?” To enhance their simultaneous but parallel conversations, the characters don’t even speak the same language; Jeanne speaks English while Bastien answers in French.

Sometimes he even looks at himself in the mirror while addressing his interlocutor. Matranga plays with crossed gazes to convey visual cross-purposes; characters rarely look at the person who is talking to them or listen to the person they’re looking at. This is very obvious in FANFU (2015), a video produced on the occasion of the eponymous show at the Palais de Tokyo. “The strange thing is that the actors focused only on their own character,” said Matranga in the interview that accompanied the show. “I thought this worked very well, because it was all about people who don’t listen to each other, who are really self-centered.”

There is a certain idea of permeability in Matranga’s practice: Her perception of movie production contaminates the way she produces pieces that themselves contaminate the occupation of a given space and the work at the studio. “The way I gather people to work with me is quite precise and focused,” she says. “What interests me is the way ideas circulate in the studio and fit into the production.” Although she clearly carries on a tradition of psycho-domestic sculpture in the vein of Heidi Bucher or Rachel Whiteread, or even Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Matranga brings into the game a very generational way of being and working together, always in polarity with the other: a friend, a collaborator, a provider, an actor that will create a context in which tension and complicity coexist. Her multifaceted approach to the making of the works is truly timely and yet very peculiar in its execution. “At the studio there are always lots of people giving their opinion all the time. I really like that cacophony.” In an essay about Rohmer commissioned for the catalogue of Matranga’s “FANFU” exhibition, movie critic Julien Mahon writes: “Rohmer’s heroes and heroines are thwarted shy people, desperately trying to conceal their handicap by drowning themselves in words.” Matranga herself is quite Rohmerian in that sense: Her grace peeks through her extreme timidity, which she drowns in continuous flows of objects, words, music — as if she were too humble to let her voice appear clearly. “I have no intention of saying anything about the world,” she says in typical Matranga form. “I don’t try to give a precise description of our current living and working existences.” And yet she does, in a nimble and poetic way.