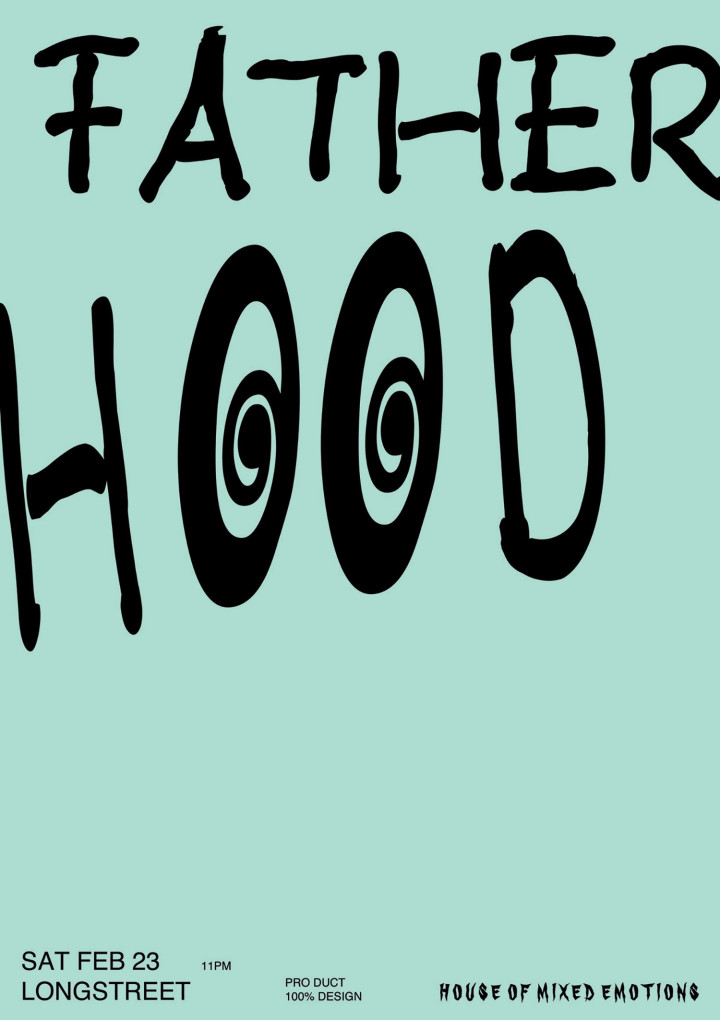

Hanging outside Zurich’s trashy but steadily gentrifying Langstrasse the other night, an older artist, who had grown up in the city but was now visiting from Berlin, opined that nothing much had changed since her days out on the town. No doubt the faces are fresher, but their attitudes are apparently the same, as is the style code (still endless variations of bomber and sportswear). Youths still frequent the same small handful of venues, and gather just as they always had in the so-called Piazza Cella. A junkie hangout by day and a bustling patch of neon-lit concrete by night, surrounded by the gritty neighborhood’s lurid bars and strip joints, it is also a public extension of the action going on inside the Longstreet Bar, an intimate two-story club housed in a generic-looking, almost suburban building. Small city? No doubt. And yet, House of Mixed Emotions (H.O.M.E.) — the sporadic club night at Longstreet that Mathis Altmann, Lhaga Koondhor and Jan Vorisek have hosted since 2011 — has certainly evolved as it celebrates its fifth anniversary this year.

Hanging outside Zurich’s trashy but steadily gentrifying Langstrasse the other night, an older artist, who had grown up in the city but was now visiting from Berlin, opined that nothing much had changed since her days out on the town. No doubt the faces are fresher, but their attitudes are apparently the same, as is the style code (still endless variations of bomber and sportswear). Youths still frequent the same small handful of venues, and gather just as they always had in the so-called Piazza Cella. A junkie hangout by day and a bustling patch of neon-lit concrete by night, surrounded by the gritty neighborhood’s lurid bars and strip joints, it is also a public extension of the action going on inside the Longstreet Bar, an intimate two-story club housed in a generic-looking, almost suburban building. Small city? No doubt. And yet, House of Mixed Emotions (H.O.M.E.) — the sporadic club night at Longstreet that Mathis Altmann, Lhaga Koondhor and Jan Vorisek have hosted since 2011 — has certainly evolved as it celebrates its fifth anniversary this year.

As H.O.M.E. has matured, it has become reflective of the ever-solidifying monetized cross-fertilization between art worlds and club scenes, as well as everything in between. Just as some of the performers invited by H.O.M.E. over the years — often at early stages in their careers, still enjoying insider status — went on to shape the mainstream proper (Arca’s collaborations with Kanye West and Björk are a prime example), so have the respective artistic careers of Vorisek and Altmann taken off and expanded. This fall, Altmann had his New York debut at the Swiss Institute, while Vorisek mounted a well-received first gallery solo show at Zurich’s Galerie Bernhard last winter. Koondhor, meanwhile, an established presence on the local scene, not least due to her role as manager of Longstreet, gets frequently booked to play art-fair parties across the globe while further partaking in the fashion world with notable projects such as a collaboration with the young Swiss label Ottolinger during New York Fashion Week last September.

Until now, H.O.M.E.’s identification, outreach and collaboration with other artists and performers have been borne of stylistic kinship, often established online via social media. (In fact, H.O.M.E. can be credited with bringing acts like Total Freedom or Mykki Blanco to Switzerland in the first place.) Through playing these nights together, a stage has been created for what in this city may still be considered decidedly niche and unapologetically exuberant, thereby pushing local norms of sound and identity, propositions that may go on to gain commercial acceptance and value. As H.O.M.E. retains its knack for the new, Koondhor, Vorisek and Altmann continue to locate and promote emerging talent. One such example is Lumpex, aka Rafał Skoczek, a young Zurich-based artist and musician whose first EP is being released at H.O.M.E. in conjunction with the label Forbidden Planet, run by the indefatigable Jurg Haller, himself a DJ, as well as the European half of art gallery Off Vendome. At the same time, H.O.M.E. is also currently looking back to the early 1990s, a personally formative period when house, techno and hip-hop fully emerged as forms of resistance to a mainstream pop culture gone stale. While these genres now represent hybridized mainstays of the music industry often confected for mass appeal, it is their foundationally explicit messages about race, class, gender, sexual identity and historical subjection that still communicate strongly with the party-as-actualization programming H.O.M.E. has pursued since night one. It’s therefore only fitting that, following a tip-off from Haller, they’ve tracked down The Mover, aka Marc Acardipane, a Frankfurt-based hardcore techno and trance pioneer whose 1993 sci-fi ghetto-tech track “Waves of Life” with Planet Core Productions has remained an eerily timeless killer. It’s ironic, or unsurprising, that The Mover’s commercial zenith came and went with “I Like it Loud,” a 2000s stadium anthem coproduced with Scooter, the German Eurotrash act mostly remembered for its front man resembling an Octoberfest-rave transmogrification of Billy Idol. H.O.M.E. knows history’s a bitch, but that doesn’t hold them back them from digging out and reanimating its initial promises gone awry.

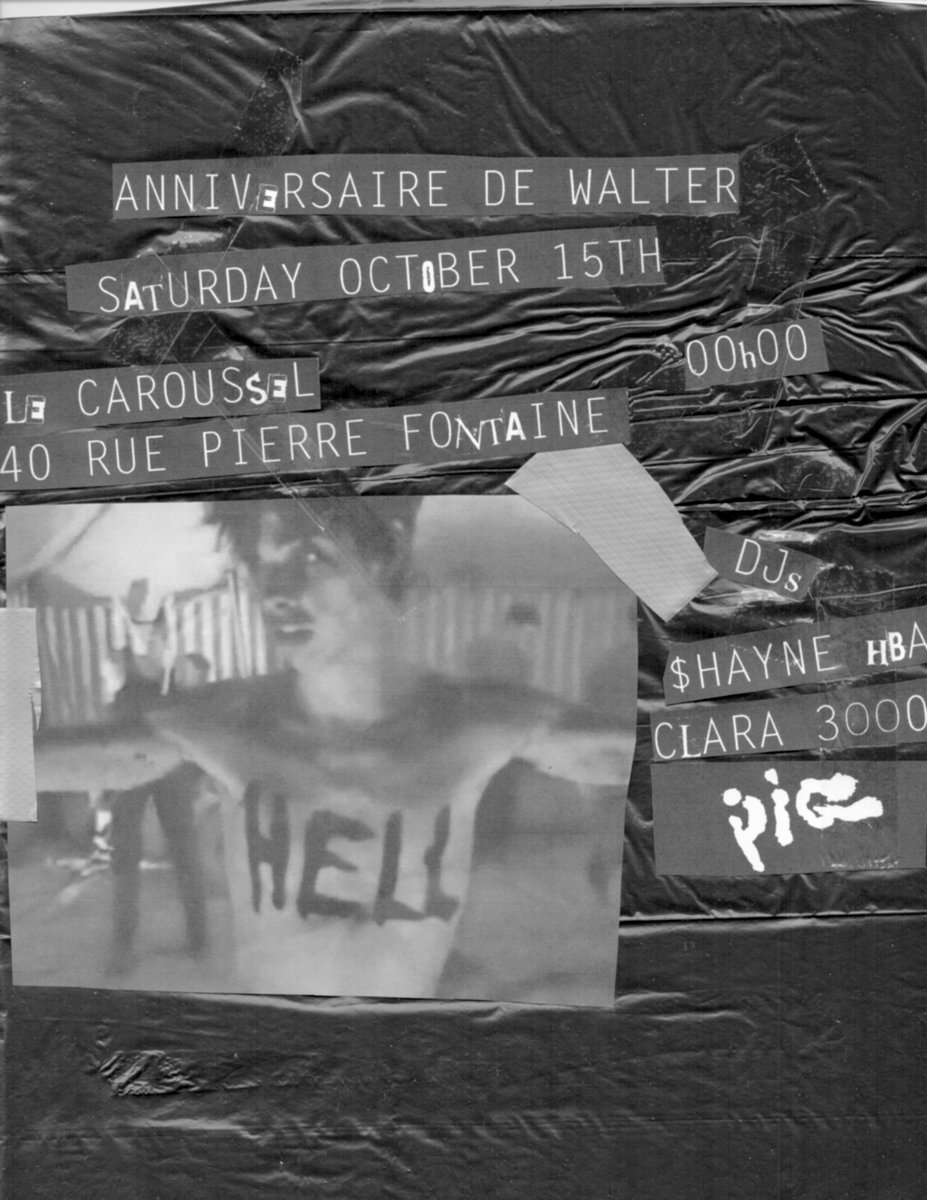

What does it mean for an avant-garde to come of age at a moment of ever-accelerating productions of youth? When the choice between personal investment in hardcore or to wholly diversify and get hired out is no longer a dichotomy but the schizo way of doing things, reflective as it is of the accepted impotence of everything that smacks of “middle” or “moderate,” in politics as much as in economics? Not long ago Hood By Air’s Shayne Oliver was quoted lamenting the quickening pace of the industry’s pick-and-mix tactics, with idiosyncrasies being lifted from his brand’s distinct styling and PR and sold back as marketable wholesale trends, all within the same season. Vorisek recently also pointed out to me MikeQ’s critique of Apple’s liberal “inspiration” by the now-mainstream sound of ballroom culture to promote their latest iPhone. Being the microcultural engine that it is, with its corresponding potential to yield new audiences/consumers, these processes of co-optation and transvaluation are not lost on H.O.M.E since they also partake in them. Yet while Altmann, Koondhor and Vorisek may have their hands and stakes at any given moment in any of the following enterprises, H.O.M.E., since its inception, has never existed as a venue (like Berghain, for example), an institution (like PS1), an energy drink (like Red Bull) or a brand (like Nike). Rather, it is an event. Home is the place you left, as they say, while H.O.M.E. is as far away from the nuclear family, in spirit at least if not in geography, as it is consuming and energizing.

“Cutting the Bullshits” is how H.O.M.E. titled the party they threw during this year’s Art Basel, cohosted with ΥΛΗ[matter]HYLE. Vorisek’s show at Galerie Bernhard was titled “Rented Bodies,” while Altmann’s show at the Halle für Kunst Lüneburg last fall was titled “The Sewager: Zwischen Krieg und Party” (Between War and Party). All of these titles evoke the transference of symbolic capital and actual environments that H.O.M.E. deals in and within which it operates. Headquartered in a mixed neighborhood rife with parallel economies, social friction and litter, the police presence around Langstrasse is increasing, as are the city’s street-cred-style campaigns to address noise and pollution. As one local club owner has stated, “The nightlife is an expression of progressing globalization.” The same is true of art fairs, whose defining current feature is their fast-paced and largely inscrutable economy that feeds on toxic levels of consumption and partying, as if the latter served as a cathartic release of everyone’s pressure to perform, to stay relevant, to not only sell but sell right, an intoxicating detox. (It is no wonder that R.A.T., the name under which Vorisek DJs, stands for Radical Anxiety Termination.) It explains why H.O.M.E.’s “Cutting the Bullshits” held at the Kaschemme was Art Basel’s most transportative night. The cavernous place was not just lit but ablaze until long past the crack of dawn. Naturally, the hustle and bustle would return again — albeit on the fair’s official opening day, when most deals are already closed and social energy is all but effectively wasted.