If there is a narrative that dominates degenerate populist and sovereign rhetoric, it is that of the border. Whether based on gender, race, or territory, borders are reassuring liminal constructs that reaffirm centuries-old myths of identity and nation. At the same time, the resurgence of this reactionary trend has been accompanied by the increasingly evident establishment of a real state of surveillance, favored by strategic devices of control that not only govern and monitor but also direct tastes, tendencies, and desires.

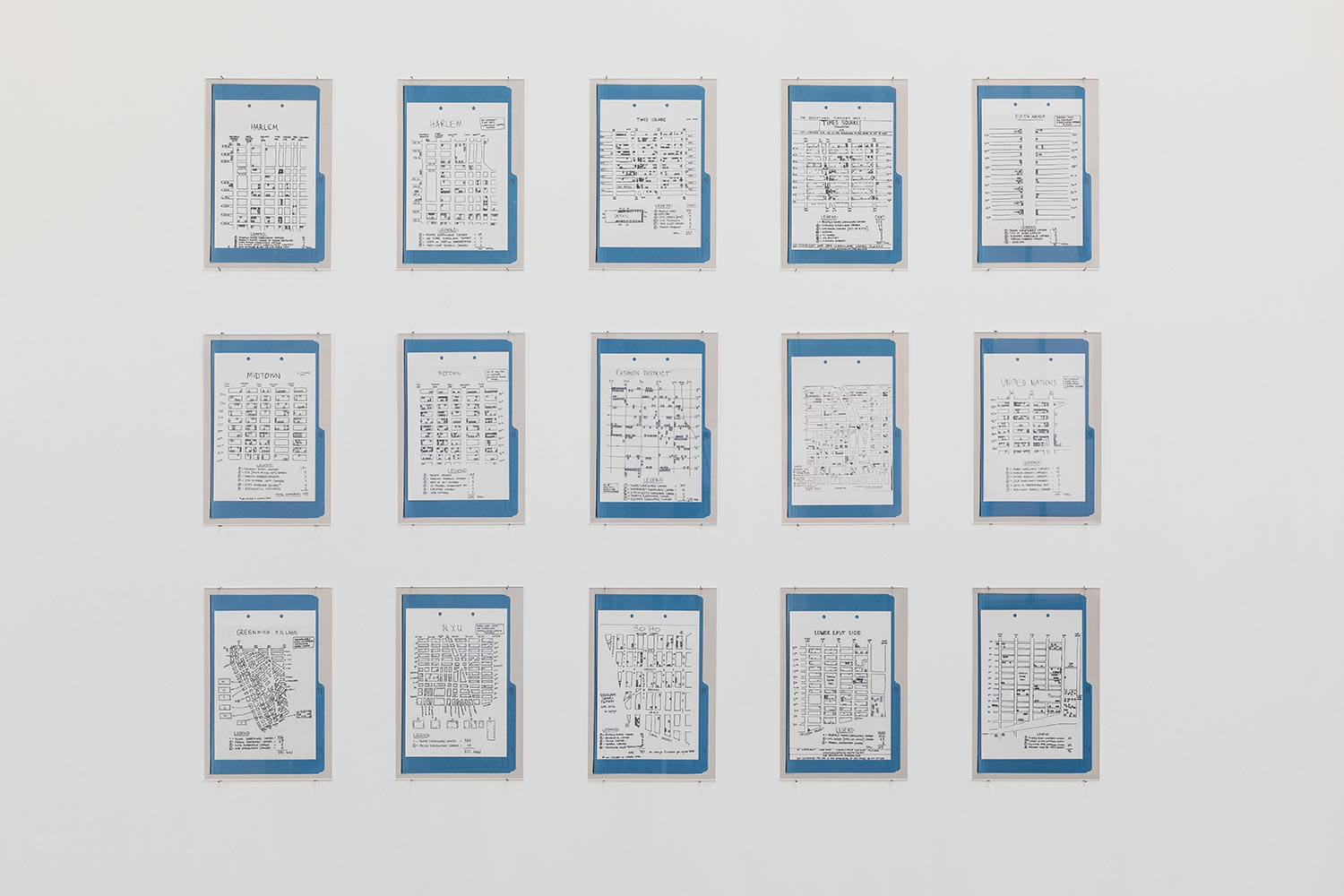

“Control” and “boundary” are the two main conceptual poles around which the survey “Homeland,” on view at the Milan-based nonprofit Ordet, is premised. The first environment of the exhibition, a ready-made installation by Hermann Pitz, Berlin Light (1994) — composed of seven original and still-functioning lights taken from the Berlin Wall — introduces motifs that develop on different levels throughout the exhibition. Besides, the program of film and video screenings selected by Ordet’s development committe members, not only reflect on the aforementioned issues but also mirror the attitude of this curatorial platform to rethink the exhibition format. The selected works seem to question the principles that inform control infrastructures, denying their function or imagining new ways of using them.

For instance, the low-res documentary 18 Days (2006) by Xu Zhen shows a group trip during which the artist, together with some friends, tries to invade China’s neighboring countries using remote-controlled toys. In On going (2019), Mohammad Eltayyeb combines found footage and images shot in Los Angeles, Jordan, Egypt, New York, and London into a frenetic montage that never dwells on a single scene yet also never leaves room for confusion: the different locations seem to merge while retaining a specific and recognizable peculiarity. It is the sense of transit that is intensified — the incessant movement from one place to another — which reinforces the notion of a nomadic and post-identity subjectivity. If in Prison Images (2000) by Harun Farocki the surveillance images take on a purely indexical value, which aims to exacerbate the pervasiveness of the supervisory apparatus, in You, the World and I (2010) by Jon Rafman, the description of such systems suggests a more intimate register. The anonymous narrator of Rafman’s film is desperately searching for an image of his recently deceased lover. Only after weeks does he manages to find one, thanks to Google Street View: the image found on the web shows a woman from behind, staring at the sea from a beach close to a small hotel on the Italian Adriatic coast.

The radical destabilization of concepts of border and control pursued by “Homeland” seems to emphasize an implicit tension — that these notions are not only ubiquitous but also already internalized within.