HOA is one of the few art spaces in Brazil — if not the only one — to have a lush, experimental, consciousness-raising program that also holds its own in the art market. Innovative exhibitions, huge parties, ballroom dances, and artistic residencies for racialized artists are all part of the ambit of this artist-run gallery in São Paulo, which has been reconfiguring the usual mechanisms for collecting and valuing the production of a younger generation of artists in the Global South.

Igi Lola Ayedun, artist and gallery director, merges celebratory practices with socio-historical resistance, revaluations of intellectual capital based on Afro-diasporic dynamics, and transdisciplinary artistic expressions in a range of media from fashion to digital art. With a background as a fashion editor, connections to the Brazilian carnival, and a personal stake in the country’s past and future, Igi decided to materialize a caring support network for artists during the pandemic, which quickly became something much more powerful.

Meet HOA: House of Ayedun.

Mateus Nunes: Igi, where would you trace the beginning of your artistic formation?

Igi Lola Ayedun: I think my formation begins with the carnival. I grew up in a samba school workshop. My father was the president of a samba school called Colorado do Brás, in the neighborhood where I was born and raised in São Paulo. My mother was a samba flag bearer. From a very young age, I understood the place of artistic expression within the body as a creative and expressive power, including the relationship with dance. And I had this very free, acute expression because carnival allowed me to have it. From accompanying the making of costumes, helping my mother sew feathers and embroideries on her skirts, to staying in the workshops watching the creation processes of the allegories and the sculptures made in the workshop. When I was a child, my dream was to be a carnival designer; every year I would say to my parents: “Show my costume drawings to your friends, I can be the youngest carnival designer at the school, they will love it!”

MN Does this relate to your solid career as a fashion editor before transitioning to the arts?

ILA Yes, this very close relationship with carnival costumes ended up making me understand that I liked to draw clothes. When I was fourteen, I won a contest at Capricho, a very influential Brazilian magazine for teenagers in the 2000s. It was then that I discovered other fashion-related professions besides design, such as fashion image production and art direction. During that time, I started building an editorial career between text and image. When I entered fashion school at Faculdade Santa Marcelina, I had already been working at a major publishing house for at least two or three years. There, I realized that I couldn’t make clothes. My highest grades were in research, creating mood boards, drawing, illustration, and observational drawing. But when it came to fashion drawing, they would tell me I was in the wrong place and that mine wasn’t a fashion expression.

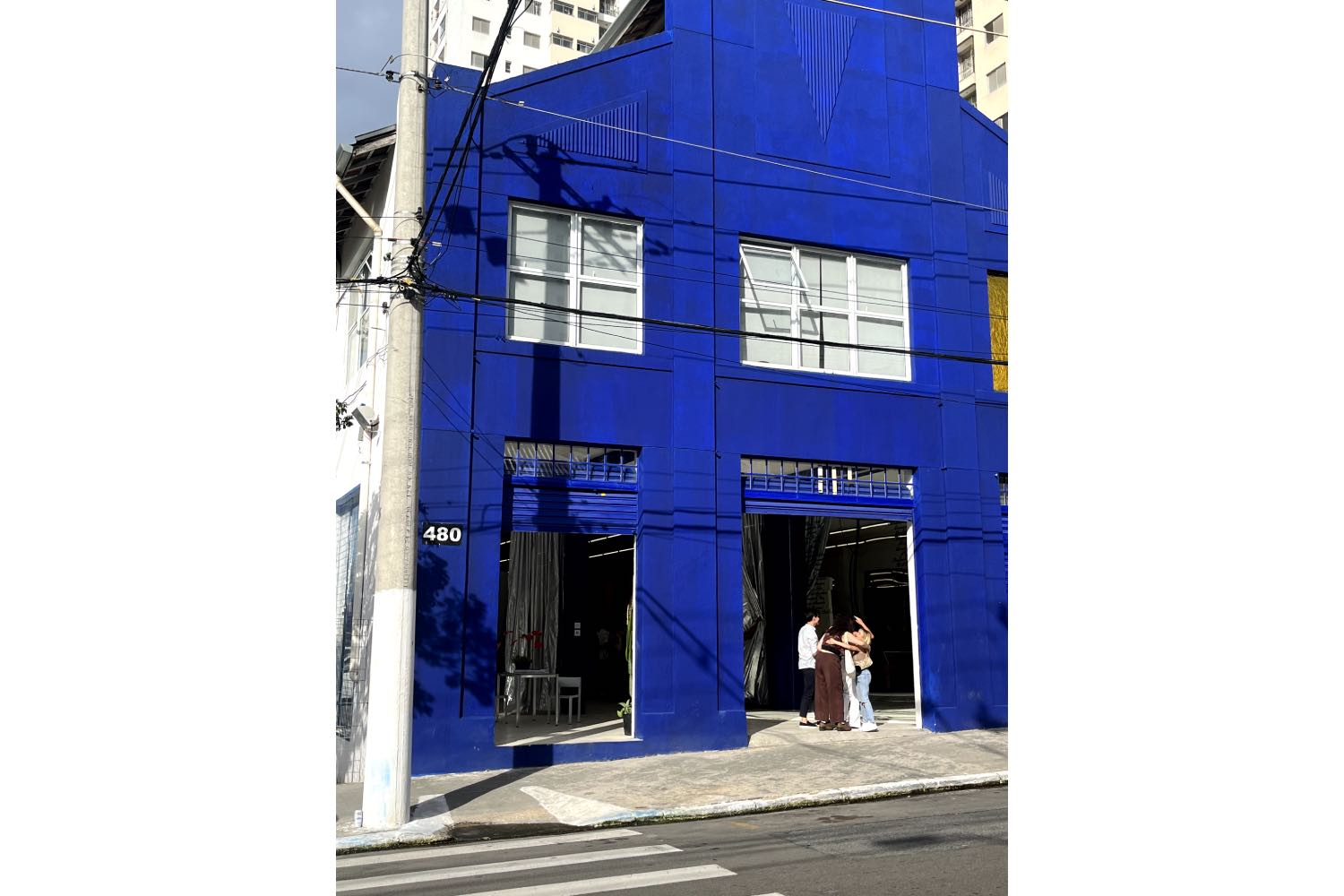

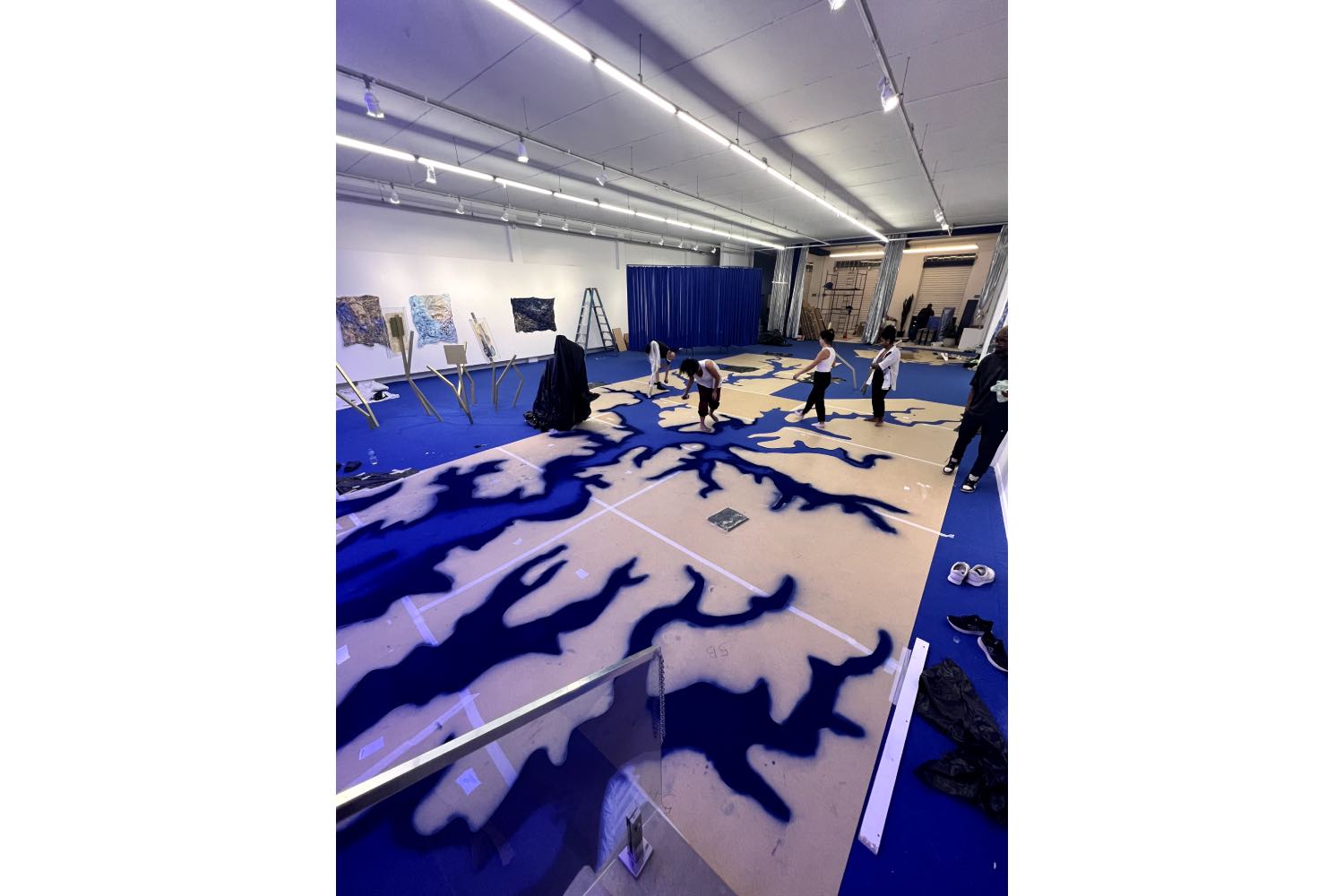

MN HOA, the gallery you opened in 2020, mixes all of this: visual art, performance, fashion, ballroom parties, a safe, joyful space for youth, dissent, and festive bodies. It’s not just stirring up a cultural and artistic scene but also a social catalyst. It’s a place for celebration, and the party never stays inside the walls of the space: when an exhibition at HOA ends, the street closes and everyone stays outside drinking. It turns into a party, and I’m often there myself.

ILA I like the idea that it’s an exhibition but it’s also a happening, a performance, a party. People are beautiful all dressed up. They meet and express themselves outside the norms of society. At HOA, there’s no normativity. I have an aversion to that absolute, chic, silent, elegant, and punctual art I experienced when I lived in Europe in the 2010s. I think this is what made me come back to Brazil and have the desire to create a space that was also a negation of that.

MN I believe that HOA has a very strong connection with popular performative expressions. You mentioned the carnival, but I was also thinking about ballroom culture.

ILA Yes. HOA, in fact, is an acronym for House of Ayedun.

MN In a way, it even replicates the model of a house, providing emotional, material, and logistical conditions for a full life for those who are part of that house. It’s like a protection, a home where people support and love each other. In addition to this constant demand for historical factors, HOA was founded during the pandemic, a time when care and support were extremely necessary.

ILA First of all, HOA is a pandemic-born company. It’s not post-pandemic, it’s not pre-pandemic. At the beginning, I was using the space as my personal studio, where we occasionally did some activations, as tiny exhibitions, happenings, open studio visits with performances, parties, etc. When I decided to formalize HOA as a company, young racialized artists were unable to produce their work due to the havoc caused by the pandemic. From the start, one of the main pillars of our work has been to offer and provide subsidies so that these artists can develop their bodies of work, both materially and intellectually.

MN Formerly, HOA operated, to some extent, within a traditional commercial gallery model. Recently, there has been a change in which the gallery no longer represents the artists it works with, but instead collaborates on projects. In a way, this breaks the Western, Eurocentric notion of the art market. Can you tell me a little more about this new phase?

ILA I can understand within the principles of decoloniality what traditionalisms and market vices do not apply to realities outside of this hegemonic cognition. From the beginning, we practiced a percentage of 60% for the artist and 40% for the gallery; imposed the use of the resale rights law on acquisitions; and elaborated contracts for acquisitions. We’ve always tried to truly honor the work of the artists with whom we decide to collaborate. But HOA is more collaborative in every way. We lost many artists to traditional galleries. Representation allowed me to build careers and design a model from start to finish. But with that came this tax burden that took on a larger proportion than I imagined.

MN Do you believe that HOA proposed a change for collectors, in the sense of critically rethinking their practice and being aware of contemporary sociohistorical debates around the globe?

ILA Many collectors began to rethink their collections by contacting us. We understood that what we do and promote is very much aligned with a global discourse, creating a market demand for works of racialized artists with a deep contemporary impact. Brazilian art collectors were aware of these changes by constantly travelling to visit the major international fairs and museum circuits. They realized, then, that collecting was incorporating a new demand for artworks in terms of a socio-historical review of the ways of collecting. When coming back to Brazil, they would ask themselves, “Oh, what do we have here that can meet this new tendency?” The answer is HOA. Some of our clients, for example, used to collect only modern art, inevitably and majorly done by white male artists. Over time, they began to look at contemporary art with a racialized perspective, thinking about native peoples and the African diaspora. By buying some works at HOA, they understood that they needed other works to create a real curatorial thread in their own collection. Interestingly, our collectors are highly qualified to be sensitive to this discourse and make the proper effort to change, but this comes with a cost for us. There is a cost in having a more subversive language towards a progressive collector who understands a bit about the importance of conservation and the creation of historical heritage from the dynamics of racialized youth. Someone who is interested in work that, although pictorial, is part of some action impacting social intellect development. And from a collector who already has racialized artists in their collection and wants to include new generations. That makes me happy.

MN You were talking about the power of youth. Compared to other galleries, HOA predominantly works with young artists. Where does this decision come from?

ILA It comes from the understanding that we deal with racism and structural colonial discrimination and that one of the main steps of harm, of cultural erasure, lies in the staining of young artistic production. If young artists don’t create art, they are not leaving a testimony of their own youth, making that youth simply not exist.

MNEven though you do a million things within HOA, there’s an overlap that I find interesting: at the very beginning, you were both the gallerist at HOA, but also an artist represented by the gallery itself. How did you reconcile the two fronts and your presence as an artist?

ILA I went through many crises with my work because I had started my research before the pandemic. I decided to sacrifice my career — or maybe just to delay it — to build the careers of other people I thought needed it more than I did, mainly in terms of access. I entered the contemporary art scene already being someone with a solid career in fashion editorial, which meant I already had close connections with collectors and curators. So, the pressure regarding my artistic production, both external and internal, was very high. Externally, there was this compulsive underestimation of the market in relation to my practices. My dynamics, skills, and everything else were questioned. I was honest; I knew how to do it, but they questioned who I was, where I came from, how I knew, how I spoke three languages, how I dressed, and how I moved in certain places. That was very painful for me. Internally, dealing with the pressure was also very costly because artists, coming from very disadvantaged social backgrounds, ended up projecting notions of success onto my life, and I absorbed them.

MN Who manages a house is a caregiver who sometimes neglects their own care for the sake of the children.

ILA That’s exactly what happened to me. There were times when outer voices would tell me I was no longer an artist, but an entrepreneur, a gallerist, a business person, because I was focusing all my efforts into building HOA, and the world inside would tell me the same. This made me start to believe that maybe I wasn’t an artist anymore, that I was taking care of the others’ artistic practice and neglecting mine. Then I knew that I needed to reaffirm the construction of HOA as a work of art. I didn’t spend three years doing nothing, not producing, not thinking artistically. I’ve been internally producing some other series of mine in the past six years. And in fact, I always did; I always took my Saturdays, Sundays, and late evening to do my own things. But everything was stored away, without results, without gaining much life, much expression, and very surrounded by this insecurity that I ended up developing from this compulsive production of negative expectations about myself and my work. But in the end of last year, I chose to do a solo exhibition at HOA [“Eclosion of a Dream, a Fantasy,” in November 2023], and a production of six years that was delivered, beyond what I devoted artistically to construct HOA itself.

MN Perhaps this history of wear and tear could have something to do with your illness process. Do you want to talk about it?

ILA I think it’s important to talk about it. The market is very cruel, indeed. It kills people. I really think we run the risk of developing cancer, as happened to me, because of the market’s tangles, you know?

MNBut you’re on a path to healing now, aren’t you?

ILA I am. I finished chemotherapy, and now I’m waiting for the next stage of treatment.

MN Using performance as a subversive dynamic to a hegemonic and sickening machinery helps in the whole process?

ILA Something that was super interesting to me was actually creating a structure that could confront the eminent structure within the logic of inclusion and make the market more diversified. And I’m sure we did that. I also believe that HOA is a situationist work of art, a continuous performance that subverts corporate codes. Like in a ballroom, in the carnival. But it subverts so well, so well, that they start to think that you are actually a big corporation, and when that happens, you end up being absorbed by the system’s vices. But that’s not why I created HOA. I created it to subvert the logic of market inclusion regarding racialized artists, and man, I feel like this mission has been accomplished.