As with many countries that possess a significant cultural heritage and who have an awkward relationship with modernity, Greece does not seem like the obvious place for contemporary art. This is not abetted by the fact that the country itself occupies an indeterminate ‘gray’ zone on the European map in general; with antiquity still a strong symbolic point of reference, but the forces of globalization very much at play, Greece is trying to come to grips with its hybrid modern identity. Never considering itself as part of the Balkans, nor really acknowledging its ‘oriental’ influences, it has mostly looked to the West for inspiration and guidance. It was also not part of the historical upheavals of the late ’80s and early ’90s in Eastern Europe and thus was not caught up in the penchant for Balkan ‘exoticism’ that pushed many artists from that region into the spotlight. Like most other small countries on the so-called ‘periphery,’ the contemporary art situation in Greece is characterized by both problems and promise.

In the last ten years there has been a marked increase in activity in the field of contemporary art; there has even been talk of a ‘scene,’ though this discussion is largely internal and serves local interests. What is a ‘scene’ anyway, and what exactly does it consist of?

It is doubtful if any curators or collectors from abroad can name more than one or two contemporary Greek artists (at best). That aside, quite a lot is happening. Consider, for example, the founding of not one but two biennials in the two largest cities, Athens and Thessaloniki.

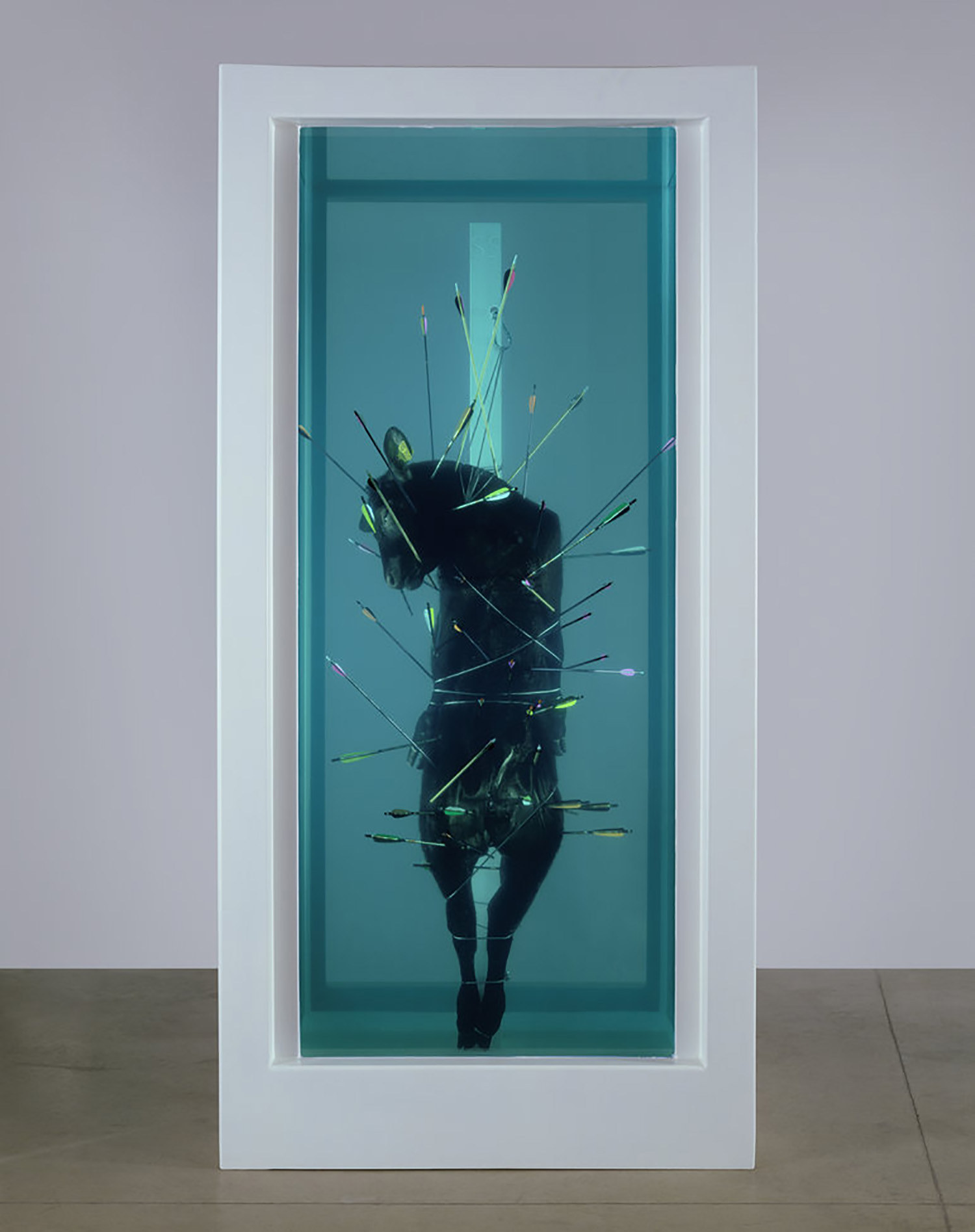

Most things of note that occur in Greece are almost invariably instigated by the private sector, which has done the most to advance contemporary art. First and foremost among these initiatives is the Deste Foundation Centre for Contemporary Art which, almost single-handedly, put Athens on the map through exhibitions drawn from the high-profile collection of its founder Dakis Joannou. Though the Foundation has toned down its activities in the last years, it still constitutes an important point of reference in Greece, especially for younger artists. However important the foundation has been in bringing international contemporary art to the attention of a wider audience in Greece, it has not really managed to promote Greek artists abroad in any significant way. The Deste Prize, which is given to a Greek artist every two years, remains a mostly local affair.

Private galleries have been instrumental in raising awareness about contemporary art. Given the lack of public money and, until recently, the lack of institutions, private galleries have played a quasi-institutional role for years. In recent years, dynamic new galleries (predominantly Athens-based) have emerged. These galleries constitute a dynamic second generation, subsequent to a handful of their predecessors who laid the foundations in the ’80s and ’90s. The newly established galleries are savvier; they have understood the importance of a good international network and visibility in international art fairs, something they pursue actively. That aside, they have been the first to really actively support and promote Greek artists internationally and to address one of the primary problems of Greek contemporary art: visibility abroad. Until now, most galleries were very good at ‘importing’ foreign artists and not so adept at ‘exporting’ homegrown talent. Now, one can slowly begin to see Greek artists exhibiting in foreign galleries and international shows. This is perhaps one of the most positive developments, as Greece does not provide an environment conducive to the production of art: opportunities for artists remain quite limited and individual subsidies are close to non-existent. The Ministry of Culture funds the national participations in biennials, but the choices are often erratic and the criteria unclear. The Athens School of Fine Arts, the ‘bastion’ of art education in Athens, is a conservative, retrograde institution where the curriculum is still mostly based on the old ‘atelier’ system. Apart from a few exceptions, the faculty consists of unremarkable artists, out of touch with international developments. As a result, most artists leave the institution apathetic and ill prepared for the competitive, professionalized environment of the art world.

What is most surprising in light of these difficulties is the lack of self-organization and collaboration among artists, and how few artist-run initiatives there are. Artists prefer to rely on the few structures that exist or to heedlessly contribute to questionable curatorial enterprises in the hope that someone will notice; mostly, of course, that doesn’t happen. Some decide to leave. Curators are in a similarly difficult position, as there are few institutions where they can make their mark, and few sources of funding to make independent shows. Nevertheless, distinct curatorial positions are missing, as is an understanding of the difference between organizing and curating an exhibition. This situation may be alleviated by a younger generation of curators who have studied abroad and have returned to Greece in the last decade. Similarly, there is a lack of critical discourse; this is not helped by the fact that there is not one publication that produces any significant work in that direction. Art magazines come and go, but their contents are a pluralist mix and match. In that sense, the demise of GAP, a freebie magazine published by Futura, perhaps the most interesting art publisher in Greece, has indeed left a gap; it was one of the few places where one could find clearly articulated opinions. The latter now are mostly expressed in more alternative journals such as the modest freebie Local Folk, instigated by artist Vangelis Vlahos and critic Despina Zefkili, and a. the athens contemporary art review published online by the Athens Biennial, both of which aim to address the critical gap. Nonetheless, when compared to other European countries, contemporary art in Greece still does not occupy a significant space in the public domain.

As far as public institutions are concerned, things finally seem to be showing some progress. Since 2000, Athens finally has its National Museum of Contemporary Art, which will move into the permanent premises of the old Fix brewery sometime in 2009, Greek politics and bureaucracy allowing (the museum is state funded). Thessaloniki, on the other hand, which is keen to challenge the ‘hegemony’ of Athens, has three main institutions: the State Museum of Contemporary Art, whose main claim to fame is the Costakis Collection of Russian avant-garde art; the private Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, which depends on donations from artists for its collection and has limited funds to make significant shows but is active on a local level; and the Contemporary Art Centre of Thessaloniki (CACT), an autonomous branch of the State Museum, which appears to be gaining in momentum in recent months following a period of nebulous choices. Generally, however, Greek museums and publicly funded institutions of contemporary art suffer from a clear direction and mission, adopting the more convenient ‘one size fits all’ mentality. What’s more, all these institutions are dealt cards from the hands of the politicians who fund them, so their status is volatile. Directors are (more often than not) political appointments, ‘players’ from the local scene. It is indicative that — as yet — there is not a single foreign director in a Greek institution.

Of all the national institutions, perhaps the exception is the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, where some sense of direction may be discerned, even though this, at times, seems to be in line with the major international exhibitions of the day. Criticism that it does not support emerging Greek artists seems to have been taken into account, and the museum is now planning a show of younger Greek artists (born after 1965) for 2008 in its temporary premises.

What Greece lacks in terms of strong public institutions it makes up for in private collections. For a small country, it boasts a considerable number of engaged private collectors. These collectors mostly buy abroad and predominantly opt for foreign artists who are seen as a more secure investment. This does not help to strengthen a weak local art market or Art Athina, the Athens art fair (now in its 13th year). There is also no system of tax breaks that would encourage collectors to play a more important role in supporting public institutions. Instead, they do that abroad.

Despite the undoubted energy on the horizon, there is still a lack of alternative spaces and independent collaborative practices. An exception is Locus Athens, a low-budget, flexible, nomadic project which, on an irregular basis, instigates stimulating exhibitions and happenings at various locations in the city of Athens. Also worth mentioning is Bios, an independent multi-disciplinary space focusing on the exploration of urban and media culture, which has a very interesting program of experimental music, film, performance, lectures and workshops. A new and promising initiative scheduled to begin operations next year is ITYS — the Institute for Contemporary Art and Thought. Set up by the former Belgian gallerist Els Hanappe, ITYS aims to generate more dialogue surrounding contemporary art and will focus on the awareness of Greece within the region, something that would indeed be constructive since it is missing in ongoing discussions.

Art production itself mostly follows the legacy of the Western modernist tradition and is still predominantly object based. The work of the younger generation tends to be quite formal and less concerned with the particularities of local context. Process-oriented, experimental, site-specific and conceptual practices, as well as institutional critique, are more rare. Lately the trend — in tune with the preferences of the international art market — seems to be characterized by a craft-based, DIY, post-punk, rock’n’roll, neo-Gothic, figurative aesthetic, with drawing being the dominant art form. One often sees examples of a naïf figuration, coupled with a renewed interest in pattern & decoration. This trend, of course, is not particular to Greece alone. Fewer are the artists whose work engages with the realities of Greece’s urban situation, or that reflect on its socio-political situation: the implications of its increased (EU aided) prosperity, its position in a rather volatile geopolitical area, or its blind embrace of globalization. What is surprising is that while Greeks in general are vehemently engaged in politics, there is an absence — indeed even suspicion — of any kind of political engagement in most artists’ works.

Few artists manage to ‘make it’ internationally, but the younger generation seems to gradually be gaining more exposure abroad. There are also a number of mid-career artists who have managed to carve out a distinct niche for themselves.

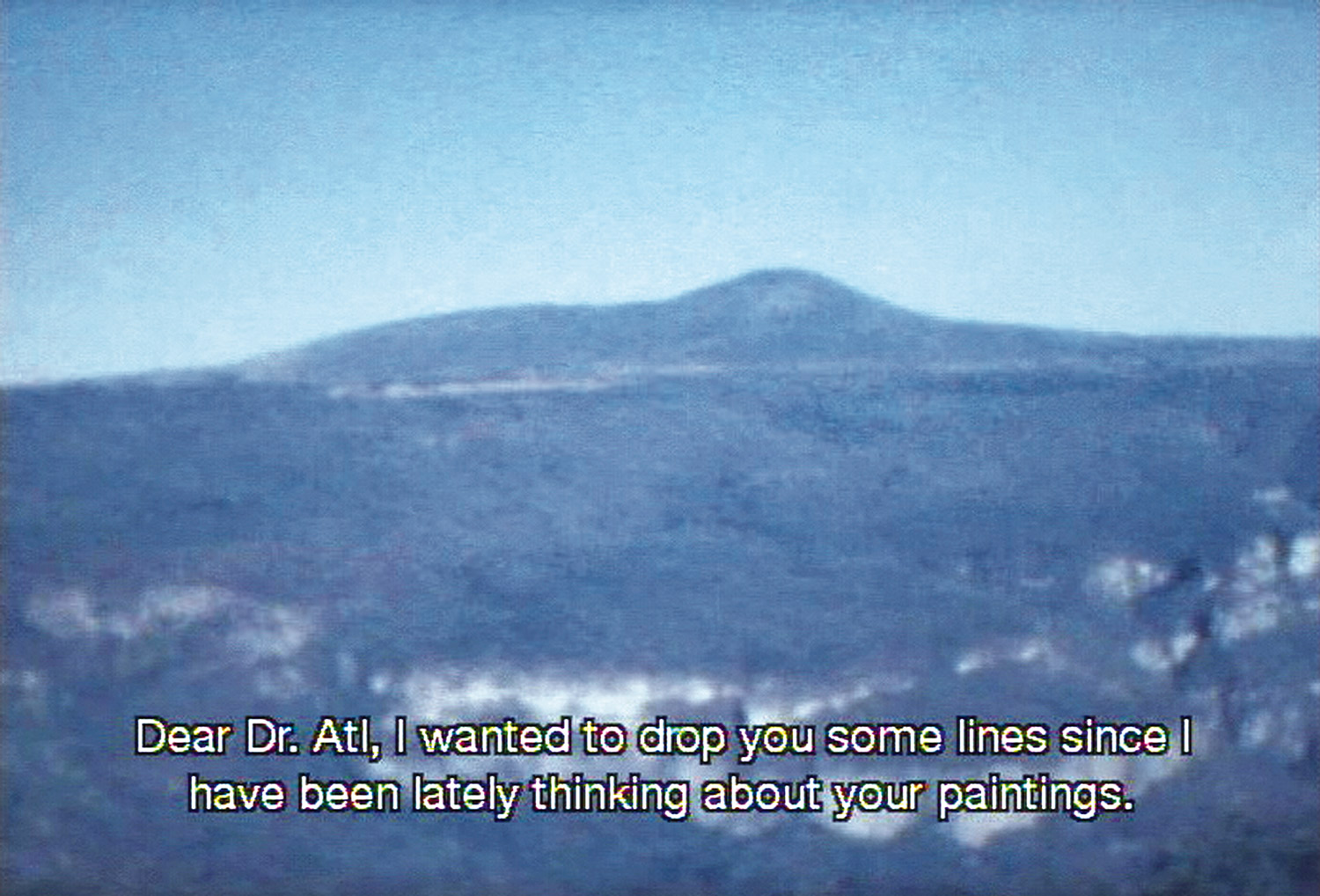

Conceptual video artist Nikos Navridis (Athens, 1958) is one of the few Greek artists who is often present in major international biennials and exhibitions. His practice — which centers around a philosophical investigation into the basic act of breathing — focuses on existential questions and states of being. His videos, both in terms of production and technology, are exceptionally sophisticated and exacting by Greek standards, in comparison to the low-tech and DIY aesthetic that is prevalent (for reasons of economy). Indeed, video and new media are still not as widespread in Greece as other European countries, and the discourse surrounding audio-visual culture and new media has only recently begun. Another internationally active mid-career artist who has been active in that direction is the US-based Jenny Marketou (Athens, 1954), whose multi-disciplinary work over the years has consistently explored questions of surveillance and the impact of technology on public life. Nikos Alexiou (1960, Rethymno, Crete), on the other hand, who represented Greece in Venice this year has, over the years, developed a sculptural and multi-disciplinary practice that often takes its inspiration from Byzantine or religious iconography, combining elements from his own heritage with the language of modernism. Panos Kokkinias (Athens, 1965) is perhaps the most interesting and accomplished photographer of his generation. His subtle, constructed photographs explore notions of alienation and the fragile relationship between man and his surroundings, whether natural or artificial. Kokkinias was also the only Greek artist recently included in Phaidon’s survey of photography, Vitamin Ph. These artists are, however, exceptions in managing to transcend the borders of Greece. Most artists still feel quite isolated, and there are high hopes that all the newly created initiatives will help to consolidate the position of Greek artists at home as well as internationally. Hopefully, in the future, artists will also be able to get better support from patrons, state institutions and galleries alike, so that they can make more ambitious work and not have to self-finance their work, as is now mostly the case.

Despite the problems faced, however, it is clear that the energy that characterizes the current situation is unprecedented. The moment is at its most opportune: if all these efforts can come together constructively, avoid customary micro-politicking and infighting, and be consolidated in the long term, the tables can really be turned. The ‘scene’ that is currently being talked about in Greece mostly revolves around the structures where art is presented and the ‘movers and shakers’ behind these. When public interest for contemporary art goes beyond its now marginal niche, when contemporary art becomes a serious item for public discussion, when we are able to talk about an improvement of the conditions for art production itself, and artists can better empower themselves, and when Greek artists are able to take their place on the international map in the long term, only then will we be able to speak of a truly successful ‘scene.’