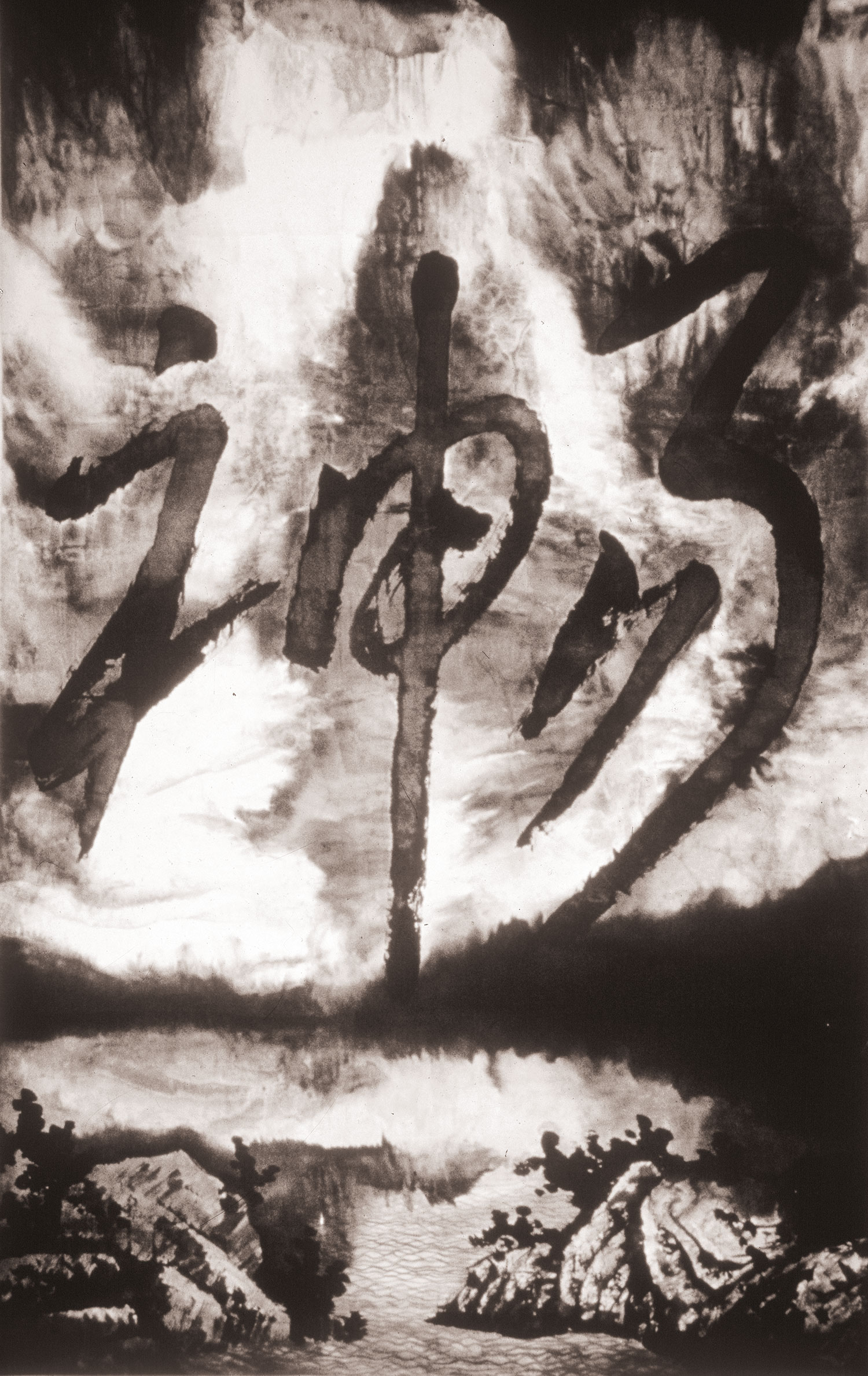

My first experience with the Grass Stage theater troupe (founded in 2005) was the production of Lu Xun 2008 at the experimental theater space Downstream Garage in the south of Shanghai. Even through the fog of my then rudimentary Mandarin, I had the exhilarating feeling that amid the dreary Soviet-style social housing, there was something truly interesting happening — a small glimmer of a civil society. The play, which used Lu Xun’s short story “Madman’s Diary” as inspiration, employed physical theater to examine the excesses of a cannibalistic, competitive society drunk on capitalism, and focused on social issues such as the melamine-tainted milk scandal. At the post-performance discussion, the audience asked the actors both naïve and incredibly critical questions, fostering emotionally charged debate. Despite their marginalized location, Grass Stage succeeded in doing something that none of the better-funded troupes had accomplished: they created a much-needed space for public dialogue.

The group is known for their well-researched, complex productions, which not only generate strong audience engagement but also tap into the zeitgeist of China’s sizeable working class. Their work takes on new relevance in light of the spate of arrests of 25 labor activists in southern China including a nursing woman and because the unions are under the government-sponsored All-China Federation of Trade Unions, workers have little leverage.

The highly sensitive content of Grass Stage productions (migration, social stratification, worker exploitation) has lead to serious scrutiny and censorship from “The main concern of theatre is social life, not by ways of reflection but that of penetration and more substantial interventions, as questions or even interrogations,” wrote Zhao Chuan in his 2006 article “Interrogating Theatre”; “This kind of theatre is, in certain ways, approaching the truths of self, individuals, and social groups; and the very process of interrogation is theatre which then becomes a method to reflect on life and its problems.”

Their rebellious stance, which is at odds with the commercial theater scene, puts them somewhat in opposition to the Shanghai-based cultural school of haipai, known for its embrace of capitalism and commercial forms. The group adopts “poor” theater aesthetics (largely out of necessity) and is composed exclusively of average-looking, non-professional actors. (The Shanghai Theater Academy, on the other hand, is known for grooming beautiful, TV-bound young actresses.) Grass Stage does not sell tickets, and it is the group’s policy to accept donations only — a necessity in order to avoid censorship or a need for official approval.

More than haipai per se, the group responds to Shanghai as a strategic locus of the Communist party and its deification of the worker. “Shanghai is an industrial, commercial city with all the foreign powers,” says Zhao Chuan. “It was one of the first cities to be industrialized, with boat building and flour mills, and it became China’s main industrial center. So there was lots of worker culture. According to the CCP it was an important industrial site; because Marx put the workers in the highest regard, Shanghai was made important.”

The group’s work also reflects the tradition of Shanghai’s history of social theater and the productions of the May Fourth Movement, which put forth anti-feudal, anti-imperialist ideologies. Like the itinerant socialist theater troupes of the 1930s and ’40s — a central part of Grass Stage’s practice is to travel to second- and third-tier cities, mounting productions in unconventional spaces for non-theater audiences. Zhao Chuan sees these “field maneuvers” as the expansion of space. “To people like us who live in Shanghai — a highly commercial environment with extremely limited living space — the field maneuvers are like the [Red Army’s] Long March (1934–35). Through the maneuver, we intend to break the confines and to construct in a larger space.” [Li Ruru (ed.), Staging China: New Theaters in the 21st Century, Palgrave Macmillian, New York, 2016]

Scholar Bo Zheng has drawn comparisons between their work and the Anyuan Workers Club’s costume lectures, which staged heated scenes of class conflict in order to stoke the emotions of the worker:

[Grass Stage’s] World Factory (2014), like the costume lectures developed in Anyuan in the 1920s, aimed to make visible the real-life conditions of the working class, and present to the audience an alternative social imaginary. However, one major difference between World Factory and the costume lectures lies in how causes of workers’ sufferings were characterized and how audiences’ emotions were summoned.

Whereas the costume lectures in Anyuan always featured characters from two opposing social classes in confrontation — workers against capitalists, peasants against landlords — and performed explicit scenes of exploitation and physical abuse, World Factory lacked any character that could be described as inherently evil. [“An Angry Committed Alliance,” in Grass Stage: World Factory Papers, OCAT, Shenzhen, 2015]

Unlike more blatantly moralistic productions, World Factory employed a nuanced mode of provocation, presenting a selection of documentary and fictional vignettes delivered in both straight and ironic modes to explore the issues that bubble beneath the surface of China’s economic miracle. Using many socialist tropes (for instance employing the “Military Anthem of the People’s Liberation Army” and the 1905 Polish Labor song “Warszawianka”), this work comments on the capitalistic, technocentric, consumer-crazed narratives promoted by Western and Chinese media as equally totalizing ideologies to those of communism.

World Factory opens with a video projection of Steve Jobs at the iPhone launch. He stands in front of a glowing Apple logo and repeats the words, “An iPod, a phone, an internet communicator,” like a kind of demagogue as Apple’s cult froths from the floor like a group of fervent Red Guards.

The actors then move into a marching formation, chanting: “I use Apple. I use banana [the name for the LG Flex phone]. Very Humane! Very Humane! I Use ZTE. I use Samsung. Very Humane! Very Humane!”

Music and parody play an enormous role in the work of Grass Stage. Such elements not only illustrate particular concepts but also help to maintain a swift pacing that keeps the attention of younger audiences, raised on the internet.

For instance, they employ Stephen Foster’s “Beautiful Dreamer” (the kind of song that one might hear in a Chinese shopping mall), which has been given new lyrics with a caustic twist: “Everyone wants a garden of freedom, but the garden always needs someone to do the hard labor. Oh, we didn’t build the tower of Babylon, we only built Disneyland.” That the original song seems to describe someone who is not living foreshadows the theme of death that develops later on in the play.

The actors then layer parody upon parody with the company’s own version of the song “Higher Being” by the post-punk rocker Dou Wei. Dou Wei’s song is a parody of an official song, “Where is Happiness?” The red version of the song posits that happiness is in “crystal clear sweat” and “meticulous plowing and weeding.” Speaking in morose tones, Dou Wei lists a series of words: contradiction, hypocrisy, greed, deception. He finally asks, “Where is happiness?” Grass Stage uses Dou Wei’s melody, offering a mordant, migrant-worker variation that includes the terms “wonderful, dreams, happiness, pride, striving, hard work, effort, struggle, the future.”

In addition to songs, the group also employs a kind of self-referential documentary theater that historicizes elements to highlight the connections between their productions — a technique that serves to galvanize the audience. For instance, they use footage taken during their research at Chetham’s Library in Manchester, in which librarian Michael Powell discusses how Engels’s father sentenced him to work in a textile mill in order to “purge him of radical ideas.” Adding layer upon layer of irony, they show footage of the Quarry Bank Mill in Manchester. The material proclaims that “180 years ago workers worked shifts as long as thirteen hours.” Meanwhile, in China, an excess of one hundred hours of overtime a month is the norm.

In one of the earlier versions of World Factory, Grass Stage actually conducted workshops at sites such as the notorious Foxconn electronics factory in Longhua, Shenzhen, which made international headlines with a rash of worker suicides in 2010.

This research enters the current production through the voices of two masked clowns who speak like old ladies gossiping in condescending tones about the death of a neighbor’s child:

“Oh, you know, they say this is a good problem — if you ask the right people. Ha ha ha ha. In psychology there is a phrase called ‘anti-frustration ability.’ That means how to find the positive in the setbacks we face in life. In the factory, there are young people; they are pitiful and unloved; their health is bad; they are emotionally vulnerable. These kids bump up against some problem and they can’t handle it, and they jump off a building, ah, ah, ah, ah, ah.”

As the clowns are acting out this scene, we see a scarecrow-like version of a corpse filled with tissue-paper figures. The clowns gather around the corpse and take out the stuffing, examining each little paper person for defects.

As the play winds up, they confront the audience with a poem, “I Swallowed a Moon Made of Iron,” by the famed Foxconn worker poet Xu Lizhi, who committed suicide in 2014:

I swallowed a moon made of iron

They refer to it as a screw.

I swallowed this industrial sewage, these unemployment documents

Youth stooped at machines die before their time

I swallowed the hustle and the destitution

Swallowed pedestrian bridges, life covered in rust

I can’t swallow any more

All that I’ve swallowed is now gushing out of my throat

Unfurling on the land of my ancestors

Into a disgraceful poem.

Leaving the audience in a suitably somber state, the players proceed to exit their characters, introducing themselves by their real names and initiating discussion about how to become a conscious consumer or the Korean labor activist Jeon Tae-il and his role in bringing about a more democratic Korea. In theater, these topics set the stage for the final act, which was an hour-long discussion with viewers, several of them moved to tears, voices trembling as they discussed the sacrifices their parents made in order to provide for them.

Unlike the down-at-the-heels Downstream Garage, where they performed for many years, last January’s performance of World Factory was held in the Micro Theater of 1933 — a converted colonial-era abattoir turned retail entertainment complex in the Hongkou District of Shanghai. Nestled among the concrete cattle chutes, where cows, disoriented, would be lead to their death, were wedding photography studios and coffee shops filled with giant stuffed animals. The architectural mechanisms of this killing factory, designed to conquer through confusion, combined with its transformation into a playground for young Shanghai white-collar consumers (those who are largely unaware of the working conditions in China’s second- and third-tier cities) lent an ironic site-specificity to this profoundly important work.