I’ll build a stairway to paradise

With a new step every day

I’m going to get there at any price

Stand aside, I’m on my way.1

I never used to think too much about Gordon’s work. I used to think because of his work. I was usually excited and encouraged by it. It was very full of energy. Gordon’s work made everyone around him more “alive.” Now I may “think” that I was excited by the forms he made, of which I have seen an enormous number of photographs in preparing to write this article, but when he was alive, it was more like standing up in the theater and shouting “bravo.” What I would actually do was give Gordon a great big hug. Also, I suppose I never thought about it because I didn’t think he was going to stop doing it. Gordon’s work was many things. All the people who ever interviewed him had a different interpretation of it. In his interviews, Gordon went off on lots of different tacks depending largely on what the people around him were saying. But the work went on. Most of it turned out to be evanescent; for one reason or another it evaporated almost as soon as it was done. Although it was hardly made before a live audience (unless one happened to be there at the time, as people often were), in that sense Gordon’s work had an aspect of the performance art which was so important when Gordon began to do his work. But most of his work was not much of a performance — it was really his life that was the show.

He was exciting to be alive with. Everyone around him was usually encouraged, unless they were not. He helped to create a community of artists and friends. This aspect of him shares something with the old-fashioned Fluxus people, but he wasn’t at all involved in their literary problems and poor-mouth concerns. When Gordon thought of something, he went ahead and did it. His daredevil antics both at work and at play frequently caused people to advise him to be careful. Swinging in the air was one of the things that he was concerned with, but not exclusively. I like to think of Gordon as a great power-tool-wielding ape making trees of his own design out of stupid, used-up architecture. His eight arms and six legs were hardly adequate to do what he had to do, and although he often had assistance, he always had to do practically the whole thing himself. Thus, he was powerful, and at this point I suppose I might mention the pun in the article’s title, G.M.C. It stands, in American, for General Motors Corporation, a large manufacturer of cars, and it is used by them as the brand name of their line of trucks.

Gordon Matta-Clark was one of twin sons born in 1945 to Ann Clark, a lovely American woman, and Sebastian Matta, a rich and famous surrealist from Chile. He grew up in Paris and New York, with a few trips to Chile, and then he studied architecture at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. With Jeffrey Lew, his best friend for many years, he helped to found the famous 112 Greene Street Gallery (now moved and known as 112 Workshop) where half the new art of the late 1960s and early 1970s made its debut. There, Gordon made a hole in the floor with a saw, then he made a hole in the floor of the cellar, then he planted a tree whose upper branches came into the gallery.

One of the things that’s clearest in my mind is how this interest in working with buildings originated. It evolved out of that period in 1970 when I was living in the basement of 112 Greene Street and doing things in different corners. Initially they weren’t at all related to the structure. I was just working within a place, but eventually I started treating the place as a whole, as an object.2

Even later he was still digging. At the Yvon Lambert Gallery in Paris, on the lam from his hectic life in 1977, he kept on digging the hole in the ground, illuminated by a light bulb, until the exhibition was over. It became five meters deep. Gordon investigated all kinds of underground spaces. He went all over Paris and New York in wine cellars, sub-basements, sewers, grottos, caves, abandoned tunnels and transportation systems. It was a great investigation. He tried to record it on film and in pictures which occasionally capture an instant of his obsession with the earth. He was always trying to figure out what to do underground, but his best works weren’t done there at all. I think the massiveness of the Earth itself was one of the few things of which he stood in awe, and it was one of the few things strong enough to stop him.

A cut and a slice — is there any question when a cut and a slice are just the same? A cut and a slice have no particular exchange. It has such a strange exception to all that which is different. A cut and only a slice, only a cut and only a slice. The remains of a taste may remain and tasting is accurate.3

Another thing that Gordon was was a photographer. His underground interests were extensively documented. I like the ones that are wide thin portraits of the traveling murals on the New York subway cars, which were photographed in black and white and colored by hand. A medium-sized archive of photography is about all that remains of his work. Not all of these photographs are documents of holes in the ground and swings in the trees. Quite a few of them are works of art and they are intended as such. Many of these are in color. There should be one of these color works on the cover of this magazine, one of the ones made from Gordon’s masterpiece Circus (Chicago, 1978). Looking at one of these things (which are usually not highly admired by Gordon’s friends), you get a really good picture, not of the “work” of which the picture is a number of various photographs, but a good picture of Gordon’s head at the moment he sliced up these photos and juxtaposed them in ways he could never have done in the old building where the pictures were taken. It makes the activity of slicing up buildings much more constructive.

A regret, a single regret, makes a doorway. What is a doorway? A doorway is a photograph. What is a photograph? A photograph is a sight and a sight is always a sight of something.4

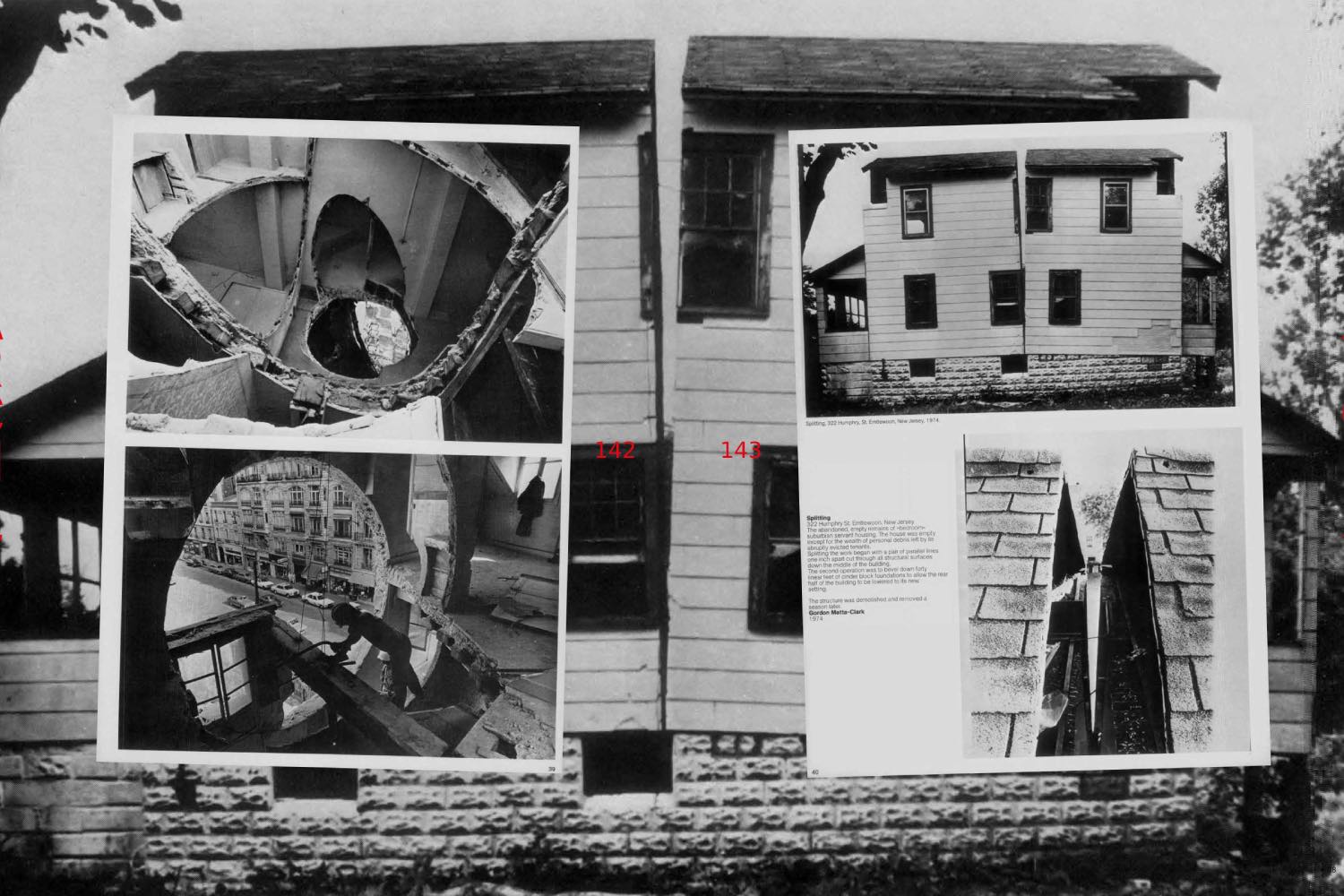

I never thought I would have to characterize Gordon’s work; I thought it was just beginning; I didn’t realize it was almost done. When he started, only five years ago, slicing up buildings, everybody, myself included, was very impressed. It was impressive. It freed us just at a moment when things were, once again, rather constrained, and painting was coming back into vogue (as it has continued to do). Slicing up buildings was a great image. Gordon was not a very large man, but his activities in these few works made him enormous. Although it was physically much more difficult than this might imply, he treated buildings like giants might treat their toys, “splitting” that house in New Jersey as if it were made of wet mud. The later cuts were almost always circular, or else shaped with curves. At first, the lines were straight and there was an inclination to wrest from the buildings relatively small souvenirs which could be crated and hauled and pushed into art galleries like inanimate cattle or something. A show of these facts was held at the John Gibson Gallery in 1974. Holly Solomon, who had provided the Humphrey Street Building in New Jersey, also showed some of the work.

When I went to Italy (1974) I was searching for places to work and Minetto Rebora of Galleria Forma gave me the office and drafting room of his old factory, a little concrete building… I cut horizontal lines that ran parallel with the floor throughout the interior of the space, so that all the walls were separated from the ceiling… There were a few points that remained holding it in place. Then I tried to make a couple of gestures that would unify the whole building. I took the center out of the roof and then another core from the top of the roof down.5

I guess, as Gordon was always saying, there are three or four important works of slicing up buildings. I only saw one of them, the one where he worked like hell for a time putting big, curved holes and a huge straight cut on Pier 52, North River, New York. It is very hard to slice up corrugated steel, of which the shed was made, and enormous wood planks over thirty centimeters thick, of which the floor was made. When I saw him after he did that, I couldn’t believe how big he was. One day I walked around on the outside of the pier shed on what was often a narrow ledge of solid wood to look at the outside of the thing — since I didn’t have a boat. It is called Day’s End (1975) and we are shown a picture of it taken from a boat. Stylistically, I think this piece was somewhat between Splitting (1974) and Conical Intersect (1975) in Paris which, however, was done before Day’s End. But it was not in Gordon to construct a logical art history from his life, any more than he would plan his moves long in advance. It was opportunism of the best sort, that uses everything at hand and whatever comes to mind with some security that it will go together well and newly. Earlier he had had quite a history of doing things with trash (nothing is more plentiful in New York) and in his last years, through various accidents, he was given the opportunity of using some real buildings that were about to be trashed by their owners.

I don’t know how romantic I feel about it. I feel very direct. It’s just that the only situations that lend themselves to the kinds of things I do bring up romantic associations. But that’s not my intention. I’d much sooner do something right across the street. I’d just as soon deal with something that’s brand new, crisp, and not at all ready for the axe.6

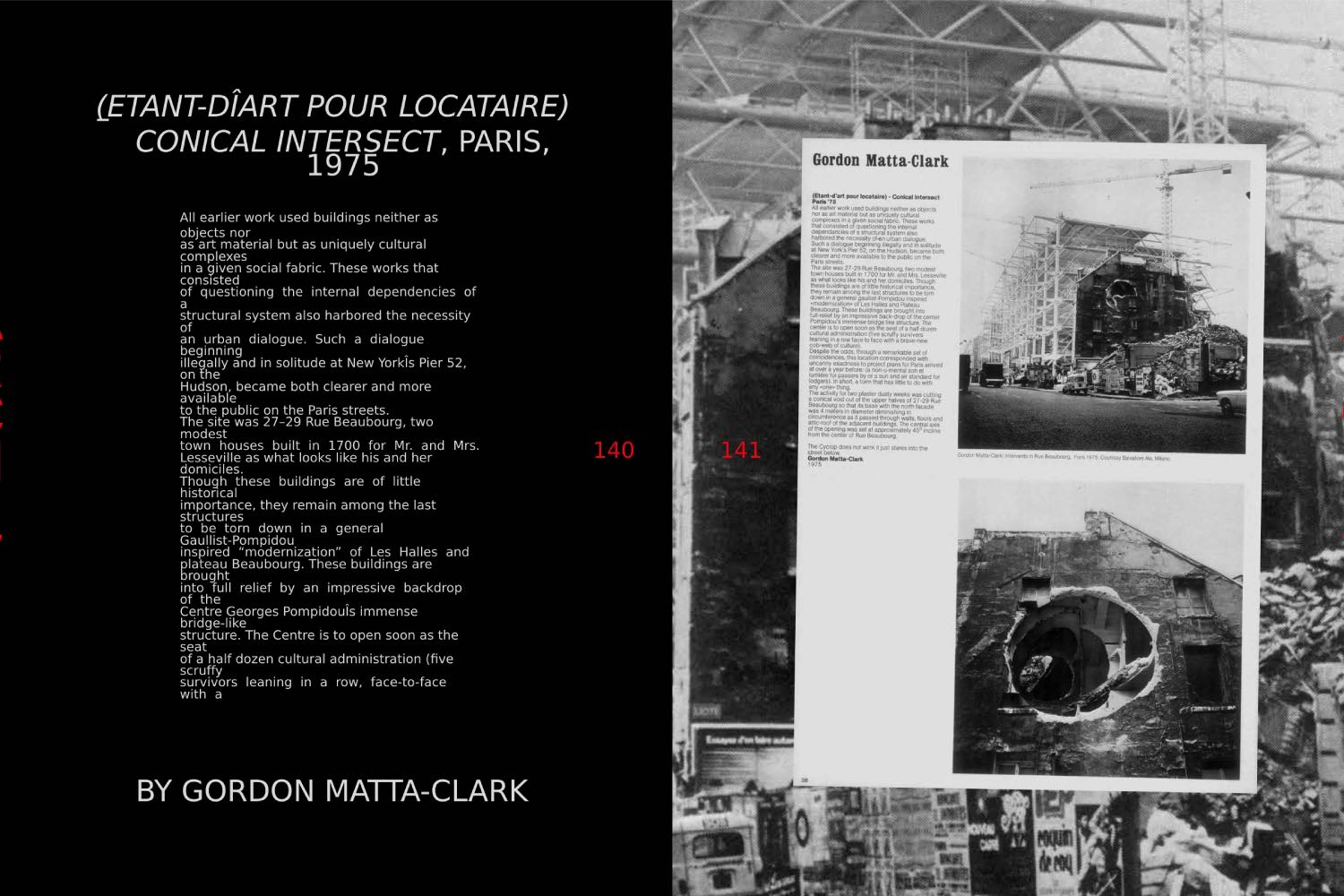

Thus, considering his close associations with Europe, to be able to use two buildings immediately adjacent to M. Pompidou’s answer to Les Halles was just about the crowning point of his career. Conical Intersect is rather simple in design, although, as always, hard to do. One cone bores its way in from one side, the other comes from the roof, and they meet. Since the cones go right through the building (solutions forbidden in Antwerp and in Chicago) it was practically the only time Gordon’s work was available on the street like other buildings. And in an important city. I wish I had seen this one. The pictures may be ever so lovely, but you can’t experience architecture in pictures. It’s photogenic, but all you get is fine pictures, not buildings. I used to get so inspired by Gordon’s work when he was at his best. That’s what a lot of it was about. Nobody could construct buildings the way Gordon destructed them. Were Gordon to construct something, it would be more like the “net” he made in Kassel. The destruction was a way of seeing through and through, in the English phrase, or of finding out a structure. I don’t think Gordon would have wanted to construct something like Conical Intersect, even if it wasn’t going to be torn down the next day. When P.S.1 opened in Long Island City, he used the occasion to find out what it would be like if there were doors in the floors. It was quite a piece. But it was thrilling to see what took place when a simple two-story house was split in two, with one end lowered to exaggerate the cut. And it was better, I think, when the pieces left over from the process were forgotten and thrown aside.

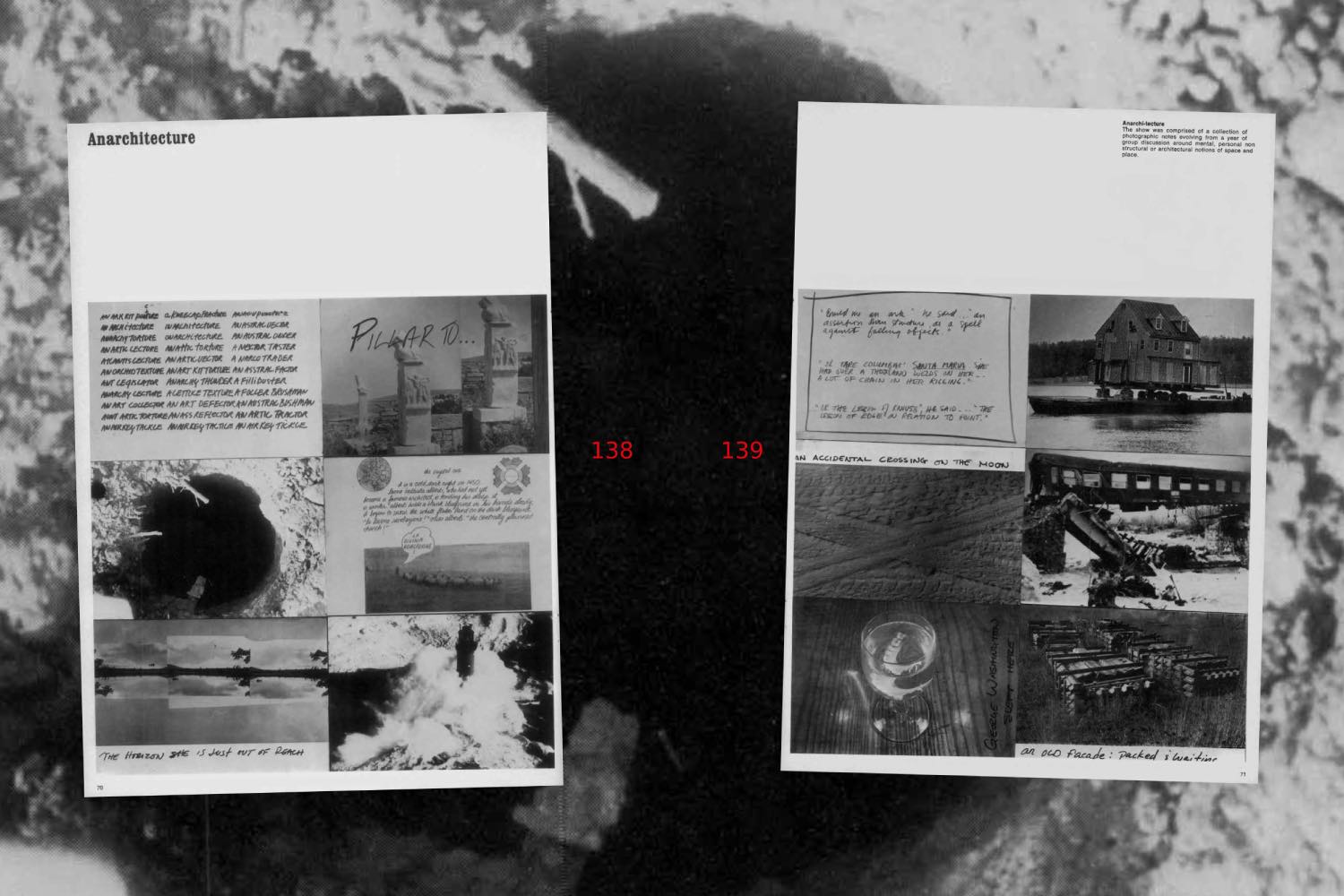

Gordon was very defensive about his work being destructive. He preferred to think of it as opening up new spaces — allowing air and sun and rain and sight to flow through like they had not been permitted to before.7

After the New York City Department of Marine and Aviation noticed what Gordon had done with their rusty, old, abandoned pier, they issued a warrant for his arrest and he fled to Paris, where he dug the hole in Lambert’s cellar called Descending Steps for Baton (1977). Baton was the familiar name of his twin brother Sebastian, who had fallen to his death from a window in 1975. This extraordinary event was to affect the rest of Gordon’s life, and he worked even harder after it. From a strictly artistic point of view, I think Gordon made two masterpieces, neither of which I’ve seen. One is Office Baroque (1977) in Antwerp, Belgium, and the other and final piece was Circus in Chicago, Illinois. As if by an oversight, Office Baroque still exists, and there is a strong movement among many of Gordon’s many friends to get the International Cultureel Centrum to keep it up as a relatively permanent example of his otherwise vanished works. It’s a big building, not very old, right downtown in the Flemish capital across the street from a castle in front of which every Flemish bride must be photographed. Much of the building, although unoccupied, is not the subject matter of the cuts he made along the walls and between the floors and through the roof, joining and recomposing the space in graceful manners which are a great pleasure to behold, even in photographs. Most of the pictures accompanying this article are of Circus and Office Baroque. I think that the beauty of these works has, strictly speaking, nothing to do with Gordon’s interest in them. Their beauty is a function of his mastery of this so peculiar an architectural material, the actuality of days gone by. I hope that the people who are trying to get Antwerp’s ICC to keep this work together succeed, if only because I would love to see it. The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago produced a decent picture-book of Circus, which was designed by Gordon but printed in black-and-white instead of color. There was a little house next door to the museum, into which the ability to display contemporary art has by now expanded, leaving the facade intact. The first display there was Gordon’s three-ring, three-story circus. A friend of mine sent me a clipping about it from one of the Chicago papers. It said they liked it but didn’t quite know why. I wish I could be as frank and thoughtless. I don’t think Gordon ever talked about what he was really doing. Perhaps at some other time it will become possible to consider his work in the context of architecture, which is a dirty word because so much crap has been put up. It is a considerable shame to have this work just filed away and sold and re-sold in the money-hedging trade of beaux-arts, because although he lived in the context of art, Gordon was not just an artist — he was an inspiration. Everyone around him felt changed by him in different ways. He was instrumental in getting artists to work together in whatever ways they could. He organized a little group that discussed “Anarchitecture” and produced an anonymous show at 112 of proposals that hardly seemed like buildings. He lived his life dedicated to his friends and interested in everything that interested them. Among his friends were people who were interested in visionary schemes of all kinds, in wind-sun-water powers, and growing things. He also liked “futuristic” things, the American cliché for the unimaginable. I met a man at Gordon’s house once who later told me that there may be a way to get marshes to produce feathers without the aid of birds. This would be good for the food chain. Which reminds me that I have not quite forgotten to mention the most inspired work, in the sense that it stuck straight up from the earth — the rope chain bridge that was hung off a seventy-five-meter smokestack in Kassel, Germany. If this were an art-history think piece, I would now be licensed to babble on about such things as what Matta-Clark’s work would have become if he had not died in August 1978, of cancer. But it is not possible for anyone, even a tiny baby or a very old person, to have lived longer than they did live. Nobody can do more in life than they were actually able to do, and no life is too short, and no life is too long. Jacob’s Ladder, at Documenta ’77, was very long and probably quite safe but very scary. You could climb all the way to the top. The picture I like best shows the net near the top looking down on the town buildings. The net itself was almost invisible, and it was not a building any more than Gordon’s other works were really buildings. Nor were they even architectural proposals. This great big net was just part of a pretty long, not very short, stairway to paradise.

And Jacob went out from Beersheba, and went toward Haran. And he lighted upon a certain place, and tarried there all night, because the sun was set: and he took of the stones of that place, and put them for his pillows, and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven. 8