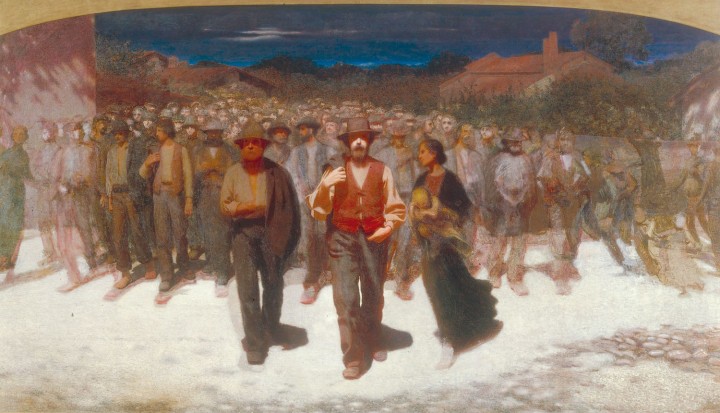

“The fourth estate” is a term that refers to a social and political force whose influence is not consistently or legitimately recognized. Of course, identifying this social and political force is contingent on the historical context in which it is registered, as well as the process by which it is historicized. Amid the historical moment in Italy marking passage from the 19th to the 20th century, the artist Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo completed The Fourth Estate, his large-scale painting depicting a procession of striking workers walking toward the brightly lit picture plane. Pellizza’s The Fourth Estate has become a seminal example of Social Realism at the turn of the century and a symbolic marker of socio-economic struggles within the shifting political histories of Italy.

Realism has always, from its earliest examples in painting tradition, been inextricably linked to the advent of the camera and photography. Photographic images provided a useful tool of reference and a measure of reality, which Realist painters utilized within a spectrum of different methods and interpretive approaches. Through use of the camera and in response to photographic image production, Realism has consistently been an effort by artists to report on their surroundings. Social Realism in particular was felt by its practitioners as a reaction to the aftermath of war, industrialization and the struggles of the proletariat and working classes to cope. Practitioners of Social Realism wanted to report on these struggles of public life, which at the turn of the twentieth century were prevalent and yet simultaneously underrepresented. It was this effort to represent in public a working poor and their socio-economic conditions that Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo pursued in the production and reception of his monumental painting The Fourth Estate.

Pellizza’s rendering of a certain hopeful reality for the Italian proletariat — one that portrays the advancing procession of wary yet determined striking workers entering into an illuminated foreground — has been a frequent point of discussion in the extensive critical reception of the painting. Recently published art-historical texts reveal that Pellizza hired individuals, many working poor who had been assembling and striking in the town of Volpedo, Italy, where the artist lived and worked, to pose for photographs that he then used as reference studies in creating the painting itself [Il Quarto Stato, Museo del Novecento, Mandadori Electa, Milano, 2013, p. 48]. The ten-year preparatory and drafting processes, as well as the Divisionist technique of painting that Pellizza employed in creating The Fourth Estate, continue to be significant points of interpretation for art historians and scholars today. And a critical reception of The Fourth Estate’s symbolic systems and allegorical significance as it reflects on the Italian working class and their social and economic conditions importantly extends to discussions on the large-scale format of the painting. At eighteen feet wide and ten feet in height (545 x 293 cm), the enormous size of the painting has had a significant determining influence on the possibilities for its display. Though the work was not commissioned by any municipality or civic organization, Pellizza created the painting in its grand scale as a kind of public monument to the proletariat and peasant subjects it portrayed. Beyond the obvious spatial needs for displaying the monumental painting, Pellizza sought to place it in an exhibition context that could be accessed by varied publics, including the middle and working poor classes. The artist was openly adamant about requiring a public destination for The Fourth Estate, entering it into the inaugural Turin Quadrennial, where it was selected and debuted in 1902. The first iteration of the art-and-design-focused Turin Quadrennial was indicative of large expositions at the turn of the century, which attempted to promote national identity, regional industries and cultural production within an international context. Large international expositions in the early 1900s also emerged in response to a growing need for sites of sociability, where different publics could gather and collectively interpret advantages and challenges proposed by the industrialized new century. Pellizza’s request that his painting be shown at the Turin Quadrennial was not an incidental decision by the artist—it was submitted precisely because this venue offered broad public outreach and accessibility within shifting social and political dynamics. Considering Pellizza’s specific interest in the publics’ access to his painting — a painting intended to draw public attention to the socio-economic struggles of the working classes and the poor — The Fourth Estate demands that we consider the social relations and economic conditions of its context for reception, circulation and consumption.

Pellizza’s desire that his realist tableau be displayed in a context that would be accessible to all publics did not however bring notoriety to the painting. The painting was poorly received during its debut, and with the sudden deaths of his wife and son soon after the Turin Quadrennial, Pellizza’s losses led him to commit suicide in 1907. The path of display and the process of reception that The Fourth Estate has taken following its debut at the Turin Quadrennial in 1902 further amplifies its significance within discourses of Realism, the history of Italian Socialism, as well as the politics and socio-economic conditions of public space. In 1920, The Fourth Estate was acquired through public subscription by the Civic Gallery of the city of Milan, during a period when it was led by a Socialist council. This public subscription led to the painting being displayed over subsequent decades in different city-owned public venues in Milan. During these years, the painting was frequently exhibited as a political manifesto, with its hopeful symbolism often mobilized to support political campaigns and differing, even contradictory, political aspirations at different historic moments in the history of Milanese civic politics [Ibid, p. 1]. The Fourth Estate has been on display at the Museo del Novecento, a public, city-owned museum devoted entirely to art of the twentieth century, since the museum opened in a newly renovated building in the city center in 2010. When the new building for the Museo del Novecento was commissioned, the display context for Pellizza’s The Fourth Estate became a significant point of discussion among the many different city and cultural agents involved. Pellizza’s original interests for the public destination of the painting, as well as its status as a work acquired by public subscription, informed discussions of how the painting would be installed within the new building. These two specific considerations were a mandatory issue written into the guidelines for the international selection of the architect for the new Museo del Novecento building. Ultimately, the Italian architect Italo Rota was selected to build the new exhibition space. Rota’s architectural plans, in discussion with future museum staff, city politicians, cultural ministers, scholars and art historians, contended with the painting’s public context. As final plans for the building were made it was decided that The Fourth Estate would be installed in an area of the museum prior to the ticketed entry galleries, where it could be viewed by anyone without having to pay admission [Interview with Marina Pugliese, Director of the Museo del Novecento, June 2015]. This decision that the painting would be installed in a publicly accessible location prior to the gallery spaces of the museum limited its location to two options. The first option, the museum’s main entrance lobby, was decided against in favor of the second option of creating a gallery wedged into the stairwell that leads from the entrance lobby up to the main exhibition galleries. The space of the stairwell and elevator shaft provides The Fourth Estate with a constrained, awkwardly angled gallery. These constricted circumstances remain a contentious point of discussion for city operatives and broader publics in Milan, as well as for museum representatives and other practitioners working with the painting, which over the past century has become a highly visible and frequently reproduced image that circulates in popular media.

The critical reception surrounding The Fourth Estate has been extensive in the Italian context, with numerous publications and symposia devoted to Pellizza’s most well-regarded work. Today, we might consider to what degree the greater political history of this painting has absorbed our current understanding of the artist’s specific interests for its reception, as well as its current institutional display at the Museo del Novecento in Milan. The intended public destination for the well-known painting, and its subsequent journey along that intended trajectory has been underhistoricized and undertheorized, even as its current institutional display remains divisive. This commitment to thinking about an artwork’s context, as much as its symbolic systems, is identified by certain practitioners as the work of Institutional Critique — a kind of work that focuses on the psychological, social, economic, legal and curatorial processes of exhibiting and presenting. Whether one identifies with this term or not, it is certain that the relation between art’s symbolic systems and its material conditions becomes an increasingly crucial point of reflection and reporting in the art world. Behind closed doors, artists and institutional representatives repeatedly confront the contradictions, disconnections and overlaps that exist between the claims made by an artistic work and the relations and conditions governing its context for display, reception and consumption. How to report on these closed-door discussions is a question we must not self-censor in this moment of global art exhibition practices. Both reflecting on and embodying the reportage that defines historical Realism, Pellizza’s The Fourth Estate elucidates this site of contemporary debate, providing a deep case study for recognizing the dynamic relationship between articulating and intervening in the material conditions of art, and the artistic rendering of symbolic systems.