London

April 2024

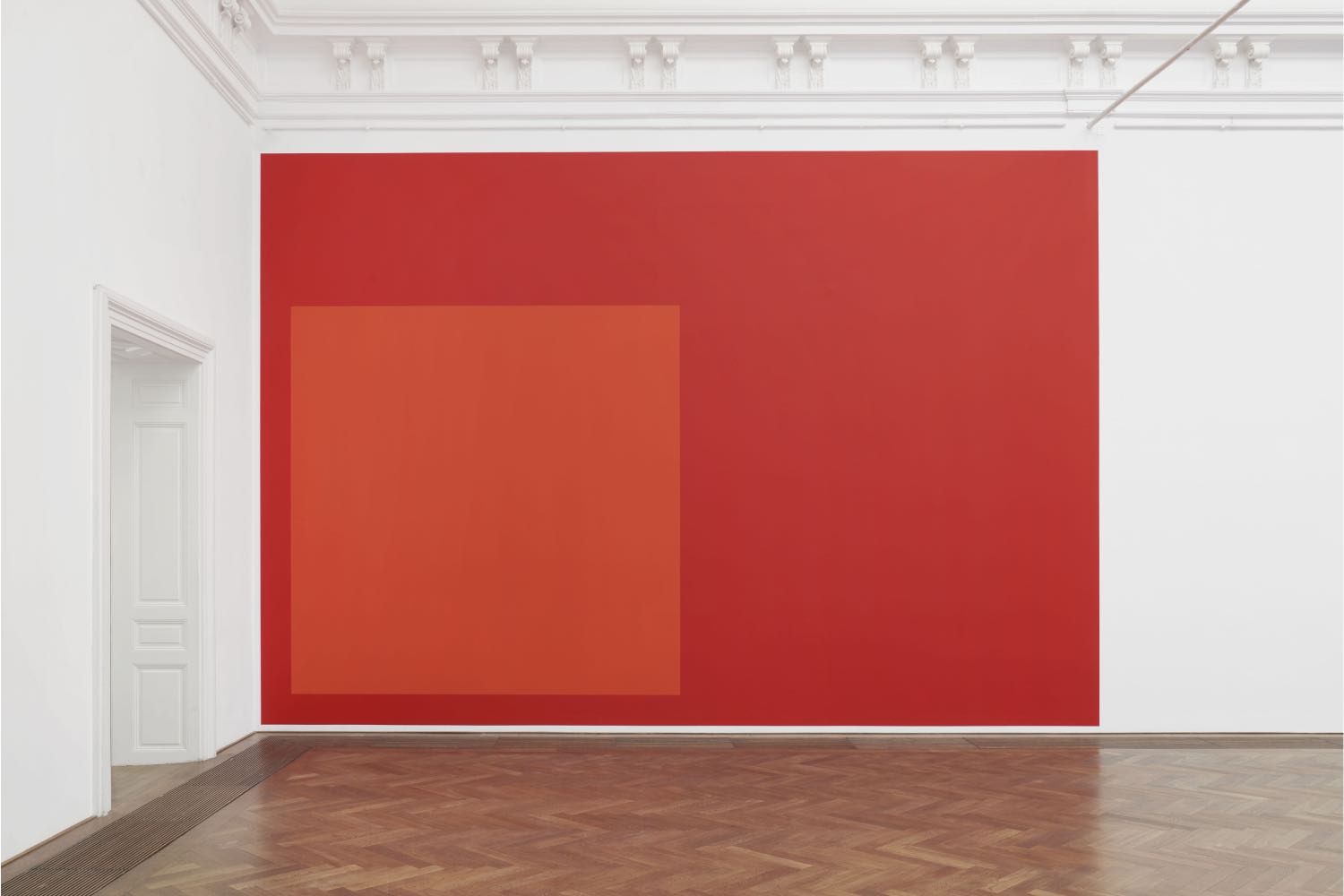

This room is the city. Before that, the ward was the city. The bedcovers mass, the sun from the window heats their fibers. The wounds are closed, but I bleed. They removed 573 grams of my body, the place my daughter first lived in. Her home in me. The place that grew with her and grew before her and grew outside of itself. So much growth. A weight of growth that made me sick with its virility. My capacity to make life incompatible with my capacity to live. That is gone now, I will have to make life differently. Time has slowed or sped or changed, exhibitions open and close. I feel her cheek pressed against mine. Everything.

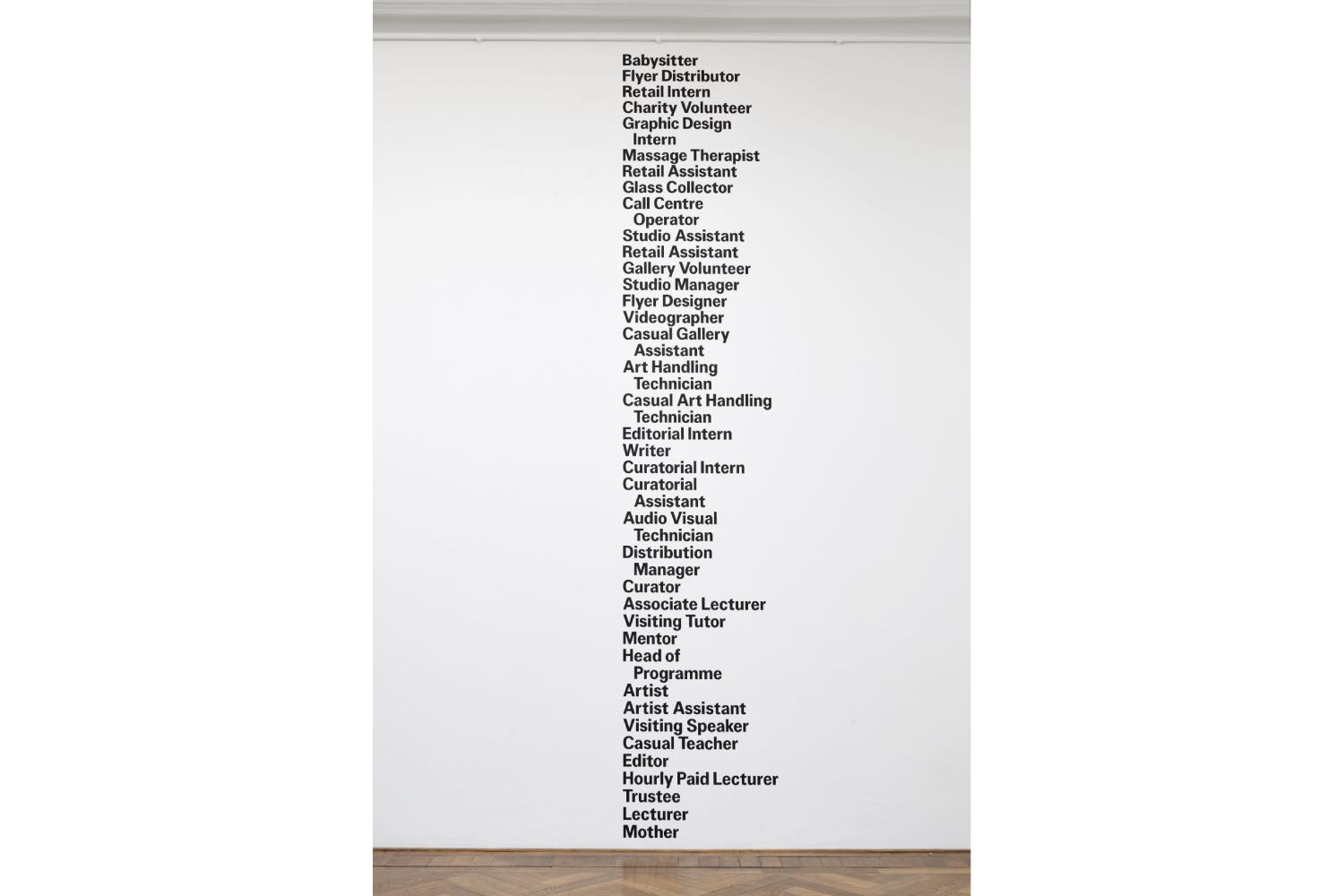

They don’t know why the growths grow. Too much hormone, too little of another hormone. Because my mother had too much hormone or too little. Because I am stressed. You say that stress is not an emotion. You ask me how I feel. I lack the words to talk about what I can’t speak. I never noticed that I got sick with my cycles, maybe because it was so slow, insidious, so many increments of exhaustion over so many years. I felt tired in the park one year, and then another year I couldn’t go to work. I never knew why. I wanted to work, to have measurable gains, a metric life, perpetual growth. Wanted this before I couldn’t work, when I couldn’t work. To not face myself, not at work, not, unknown. The work of the body that is always already happening.

Before the surgery, they put me on hormone inhibitors. One injection a month in the stomach. The city was still cold and wet, and I took the first injection with me to Chicago, implanted in my stomach, my hands too cold to open the combination lock to get the keys to the rented apartment. Without my daughter in four bedrooms, each with their covers turned over, tucked in. The radiators are loud. My sockets hurting, coughing, lagging. The implant flew back with me home. The city is opening up its roots, mild rain on my face. The implant puncture bleeding under the plaster as I carry her home. Wet kisses on my face. My stomach flattening. The third implant with the leaf buds graying and fine haired. I hide the chocolate eggs I bought in Basel in the unfinished garden.

They gave me two choices at the consultation. I could have the surgery or take a hormone inhibitor until I inhibited my own hormones at menopause. I chose surgery because they used the term “definitive management.” And because my mother had uterine cancer. My mother has no uterus or ovaries. Uterine cancer is hormone-dependent, so is breast and ovarian cancer. My partner’s sister will be on inhibitors long-term after treatment for breast cancer. The cancer her mother had. She cannot have hormone replacement. I will keep my ovaries, my hormones. I will have no periods, no uterus, no fallopian tubes, no cervix. These will no longer be in my body. I wasn’t going to use them, but I miss the unused more than the used.

I fold up my clothes and put my shoes under the chair in the day surgery unit. I breathe in deep and wake cut emptier. My teeth moving against each other in my mouth. My body heating up against its loss. I throw up water from my stomach. The woman in the next unit knows my name. She is an artist. She has had an ovary removed. She leaves before I do. They wheel me to a bed, it’s in a blood cancer ward, the heaters in the ceiling are overactive. There is no food. I eat a pack of miniature cheese biscuits, the chewed paste stuck on my dry tongue. Bags of drip, bags of medicines, the cannula drips blood. They can’t find my veins. They don’t know why my body is so hot. They use the word spike. The ward is the city. I sleep two nights. I go home.

This room is the city. The aging flowers sent by friends. Blue and purple, pinks, cream white, sprays. The framed printout of a spreadsheet I made for my partner’s fortieth birthday. The white paper hospital bags, shoes wrapped in plastic, boxed medicines. Her document folder, the one they gave us when we left the hospital, the first time we wrote her name. Piles of clothes on the floor and the trees outside the window. The broken blind propped up with a stick. The wardrobes empty. The baby monitor amplifies the drilling in the walls. I have bled every month since I was twelve so I could reproduce. I bleed now because I can’t. And then that will stop, too. The cuts in my stomach are covered in glue, and the orange dye brushed on my skin. The purpling wrinkle of the wounds. My stomach hanging over. I talk to the gallery on the phone. I tell them I won’t be there, won’t be coming. My daughter is coming up the stairs. I will make life differently.