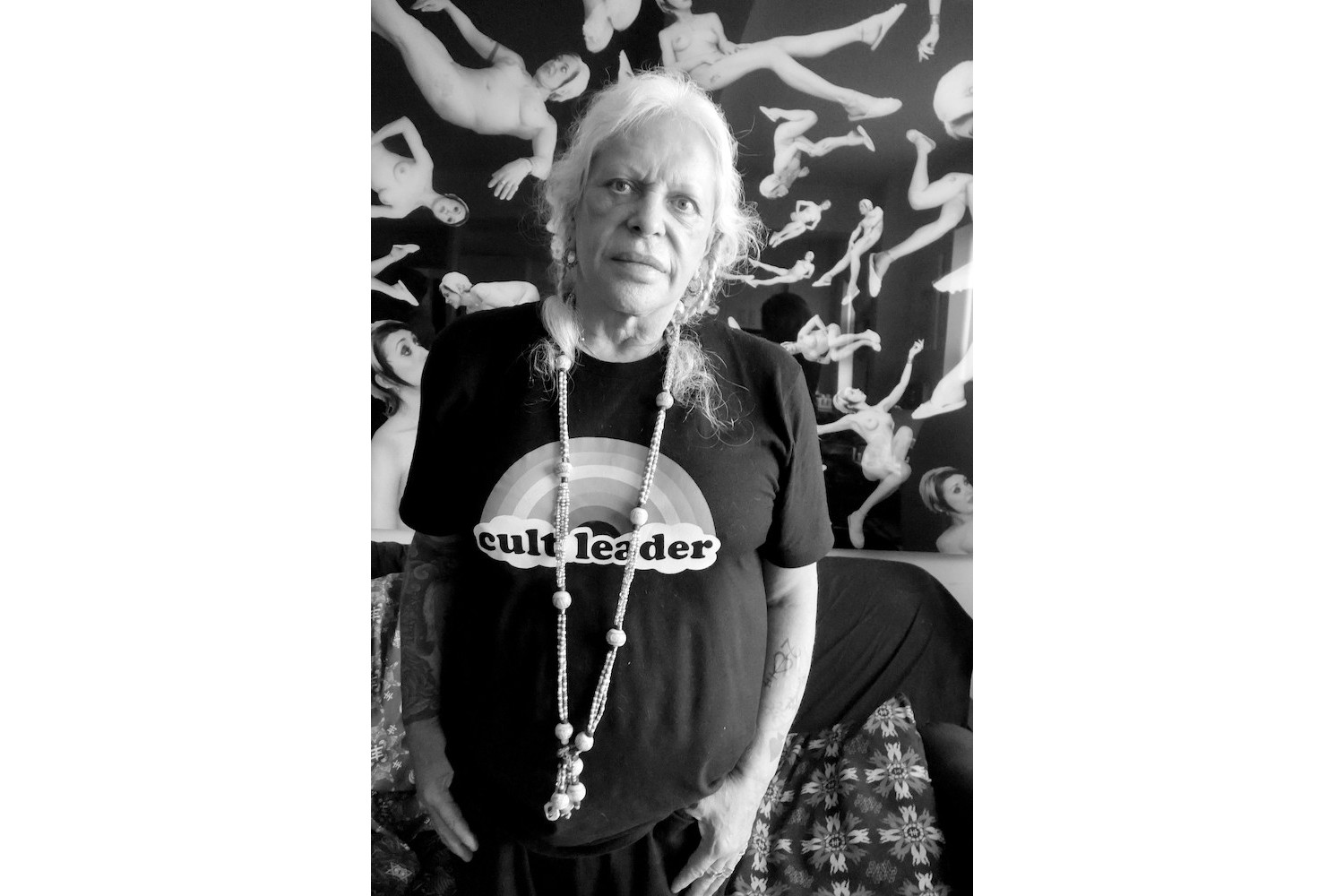

Summing up the iconic life of dear friend and legendary provocateur Genesis Breyer P-Orridge would be a daunting task in ordinary times. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and the recent death of my beloved father, it feels herculean. My grief over he/r passing on March 14, 2020, weeks after he/r seventieth birthday, was magnified by my inability to attend her eco-funeral due to coronavirus-related concerns. In the wilds of an Upstate New York hippy-dippy plot of land that allowed for such burials, s/he was to be finally reunited with her late wife Lady Jaye (née Jacqueline Breyer) in body and soul. In my place, I sent a double-headed Yoruba Shango staff that Gen had given me, and which had belonged to Jaye, who — in addition to being a nurse, dominatrix, and performance artist — was a Santeria practitioner.

It was New Year’s Eve, less than a month after Jaye “dropped her body” (as the two were fond of describing death), and we were in their Queens apartment. We’d just shared a bottle of Veuve Clicquot bought at a local twenty-four-hour liquor store, the kind with bullet-proof partitions, and taken their dog Biggie, who was aging poorly, for a walk in a pram. After s/he learned of my interest in voudou and Santeria (I’d taught a course related to women’s roles in those traditions), s/he offered it to me. Shango, I knew, was a god of virility, associated with drumming and thunder, and represented by an axe. What I didn’t know, and only discovered after Gen’s death, was that he is also the protector of sacred twins. No doubt Gen didn’t know that either, but the thought that Jaye probably did imbued the ritual object with new potency. Echoing the couple’s radical experiment in pandrogyny (2003–2007), in which they would become a third unified being through a series of surgeries designed to make them look alike, it almost seemed to anticipate it.

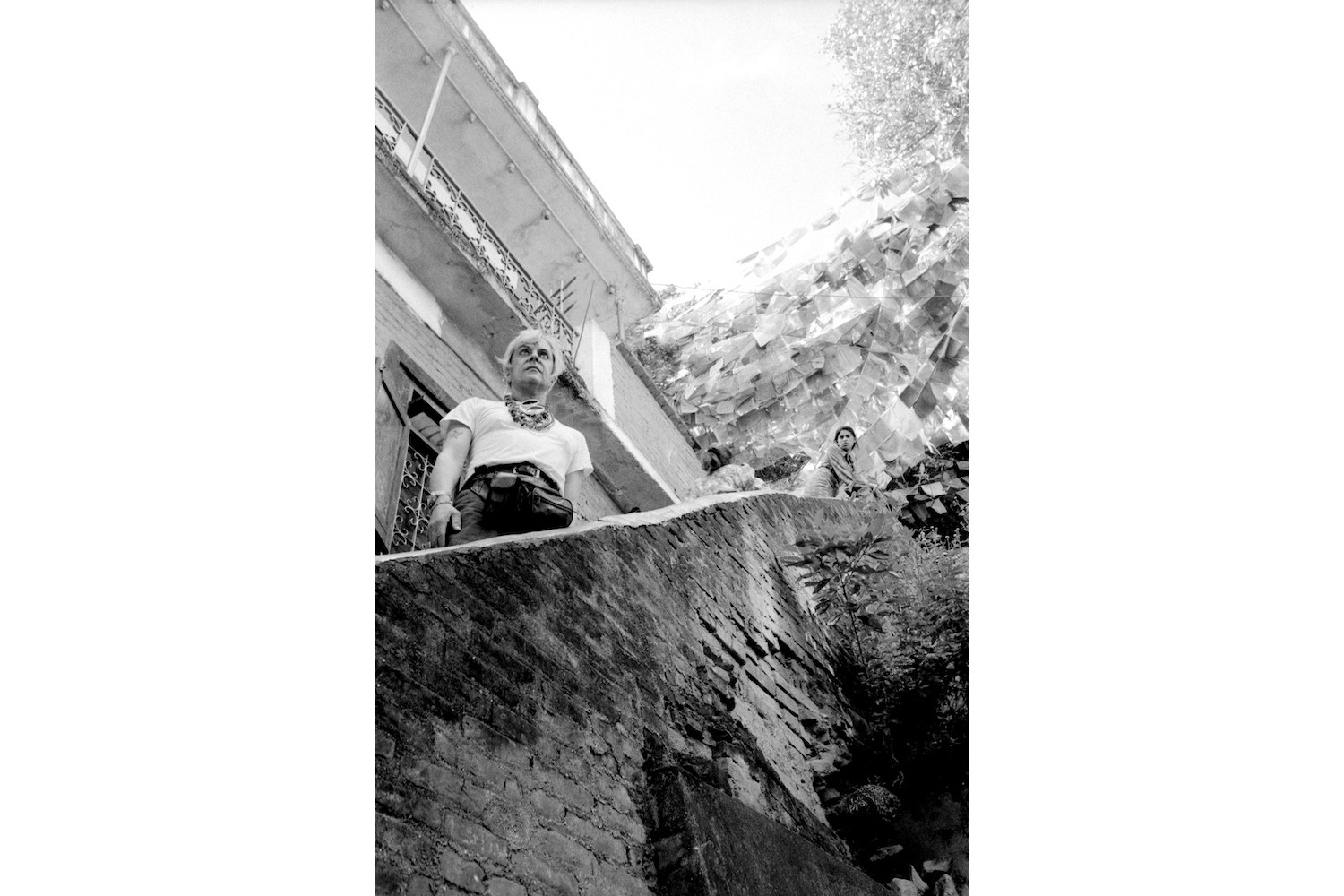

That Genesis would travel to Ouidah, Benin, in West Africa a decade later, with no prior knowledge about the Yoruban cult of twins, and undergo an initiation rite to reactivate Jaye’s spirit as he/r symbolic twin, made my discovery feel revelatory. Gen always carried the five-inch carved figurine (the receptacle of Jaye’s spirit) with he/r everywhere, having identical outfits made for it and for he/r, and following all related ritual protocols, including daily offerings of Jaye’s favorite foods, like almonds. Gen died just as coronavirus pandemonium was hitting US shores, alone in her Lower East Side apartment. And while I know, as s/he did when Jaye died, that in fact “S/he Is Still Her/e,” having that Shango staff at the funeral to sanctify their final reunion as lover-twins still gives me great comfort.

One of our last texts on March 10 reflected our mutual ambivalence about the media’s coverage of COVID-19 (like most Italians, we reflexively distrusted early reports), but our final exchange was over the radiant beauty of the full moon. In response to a picture of it I sent on my phone, s/he replied: “Very beauty full. And it’s looked like that for millennia. Before any life forms and will coumtinue long after all life forms are long gone.” It seemed to embody a subliminal reckoning with he/r own imminent passing, and our shared belief that the planet would survive the human race, which Gen often likened to a virus itself.

Born Neil Andrew Megson on February 22, 1950, in Manchester, England, from the beginning Gen proved to be a “special” child: precocious, daring, and sensitive. Pronounced dead on three occasions as a severely asthmatic child, he/r relationship to the body as something to transcend and manipulate was no doubt informed by these momentary “deaths.” The routine bullying she endured as a small sickly boy by male classmates similarly led to an early aversion to masculinity, and the kind of strict gender codes that dominated postwar England.

The child of theatrical parents and jazz aficionados, s/he saw the arts as a legitimate alternative to the kind of traditional lifestyle that others so mindlessly adopted. Dropping out of the University of Hull to join a counterculture commune with strict codes of living devised to reprogram the brain was, like he/r exposure to Surrealism, a foundational experience in he/r evolution as a self-designated “cultural engineer.”

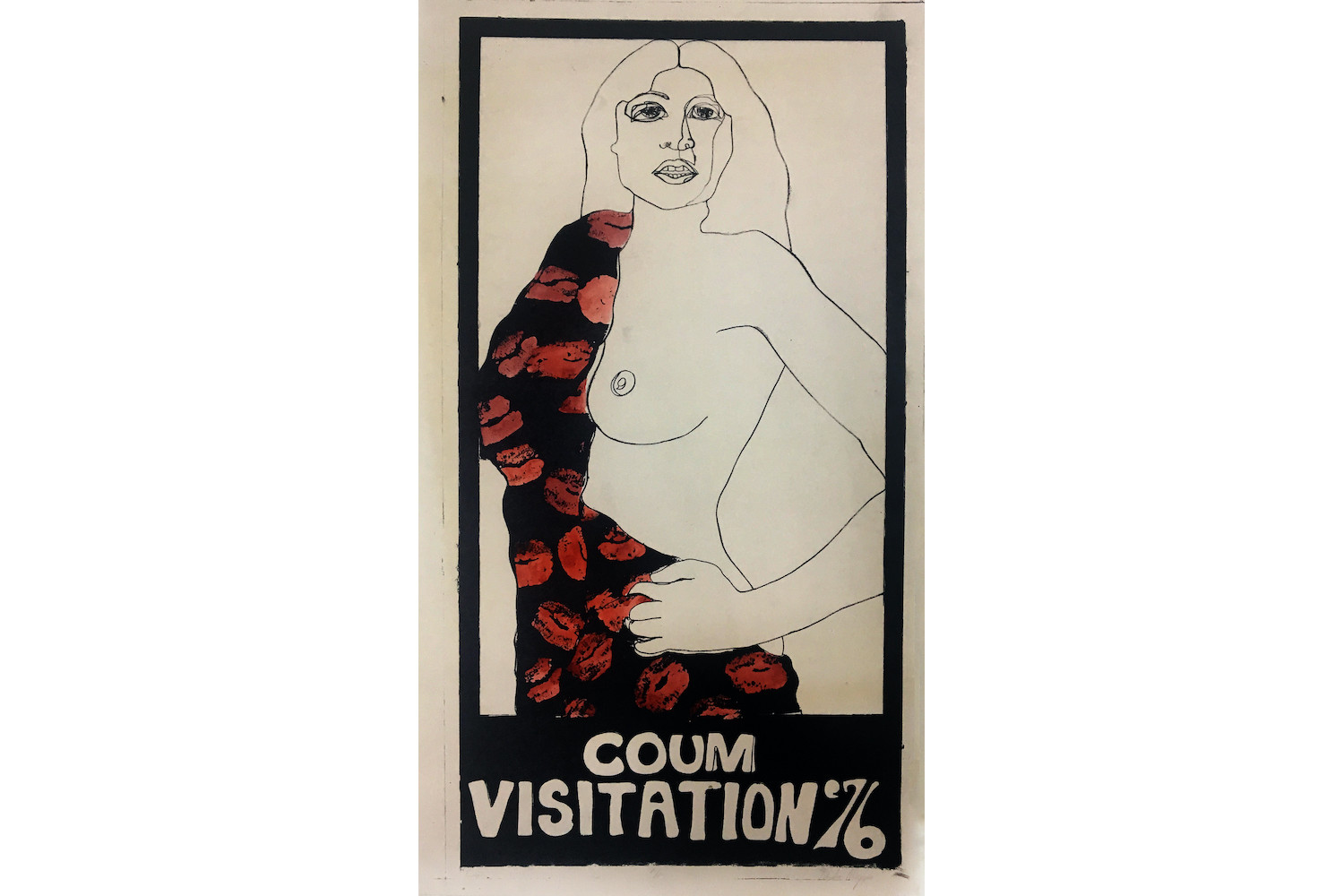

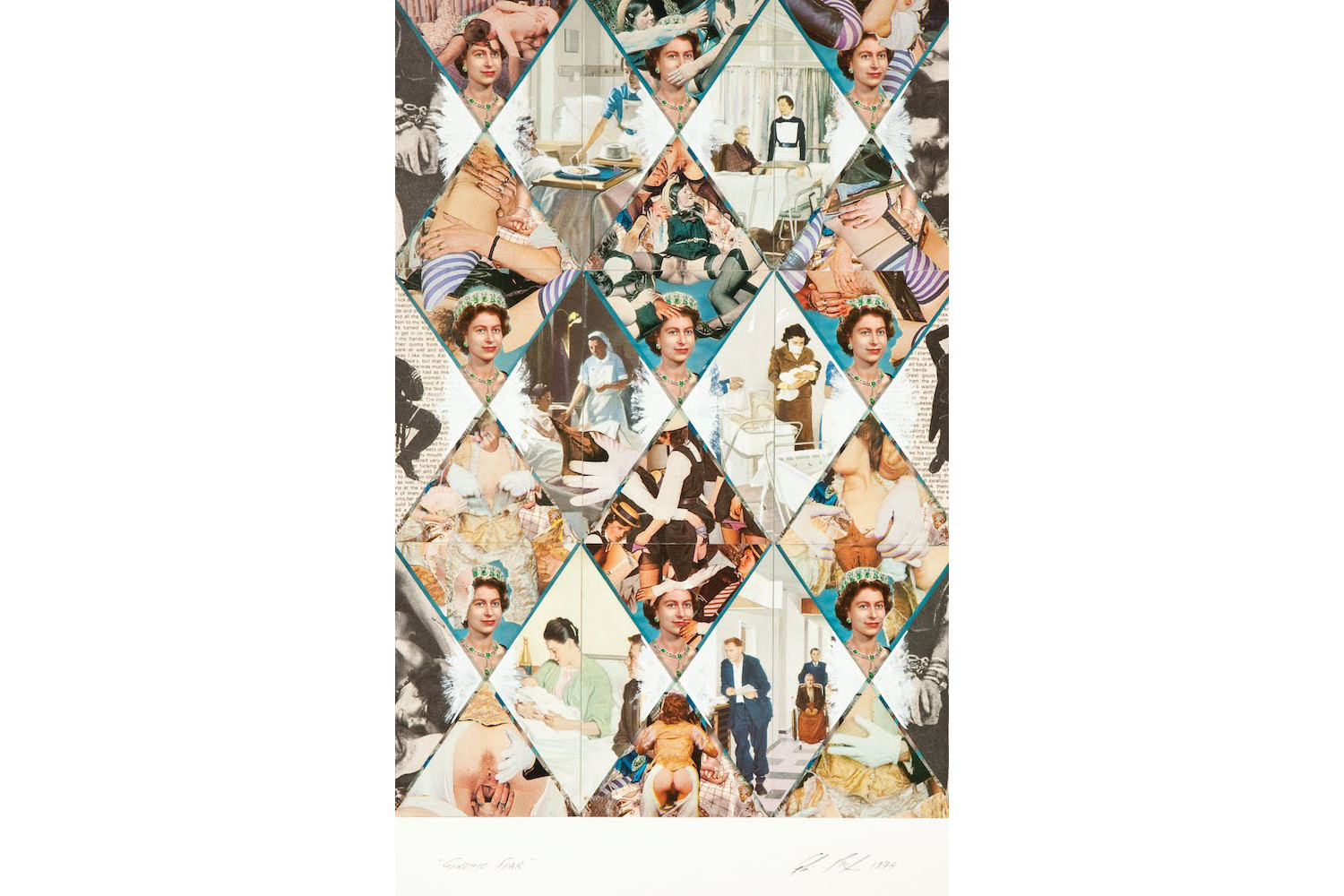

When s/he founded the Fluxus-based collective COUM Transmissions in 1969, s/he attributed its creation to a vision s/he had on a road trip. As with everything s/he undertook, Gen had no intention of repeating what others had already done. From the beginning, COUM uniquely infused the Fluxus aim to merge art and everyday life with the shock tactics of Viennese Actionism; the cut-up techniques of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin; the occultism of Austin Osman Spare; and he/r inimitable wit. He/r subversive take on Fluxus also incorporated a cheeky sexuality: the group’s logo was the word “COUM” shaped into a semi-erect penis with a semen droplet coming out of the end. Gen’s participation in the related genre of Mail Art offered much the same, and included sending pornographic collages defacing postcards of Queen Elizabeth II, and a dead rat, through the Royal Mail. An example of the former, Genetic Fear, 1974, resulted in a one-year jail sentence (eventually suspended) for the crime of distributing obscene materials through the post. Like any true provocateur, it only egged he/r on.

In 1973, the artist moved from Hull to London, where s/he met Burroughs and Gysin, who became life-long friends and mentors. There, together with Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti (P-Orridge’s then girlfriend), COUM began creating ad hoc street actions devised to shock an unsuspecting populace out of its complacency and to challenge gender norms. From members pushing carts full of chicken heads and bloodied tampons through the park, to P-Orridge and Fanni Tutti swapping gendered outfits — the former removing a orange laborer’s uniform to put on Tutti’s blue evening dress, and vice versa — and modifying their body language and voices accordingly, they were alternately absurdist and political. The latter would prove to be a harbinger of he/r pandrogyny project with Jaye, which as Gen has noted ultimately began with their California wedding in 1993: “She was the groom and I was the bride,” Gen told SFGate in 2004. “I wore a beautiful white lace wedding dress with my left arm in a cast, and she wore black leather motorbike trousers, biker boots, a black leather vest with nothing underneath, and a mustache and sideburns. It was very portentous.”

COUM’s tactics quickly gained notoriety, and their infamous 1976 exhibition “Prostitution,” at London’s Institute for Contemporary Art, sent shock waves through the public and art cognoscenti alike. The exhibition featured tampons, rusty syringes, photos of Fanni Tutti’s commercial porn endeavors, and strippers in place of guards, with everything — as Genesis wryly wrote in the accompanying poster — “for sale at a price, even the people.” The show also marked the debut of the pioneering industrial music and art collective Throbbing Gristle, which COUM had transitioned into. TG’s aggressive, confrontational performances featured processed vocals and tape-based samples played through a one-octave keyboard dubbed the Gristle-izer. The percussive DIY onslaught with its unrelenting noise was accompanied by dark and disturbing visuals, which, like the lyrics Gen wrote, plumbed the darkest corners of human psychology. The group’s experimental sound-image collages referenced genocidal fascism, serial killers, horrific accidents, and occult mysticism (most infamously swastikas), turning the psychedelic era’s customary sensory overload and ethereal grooves into the stuff of nightmares.

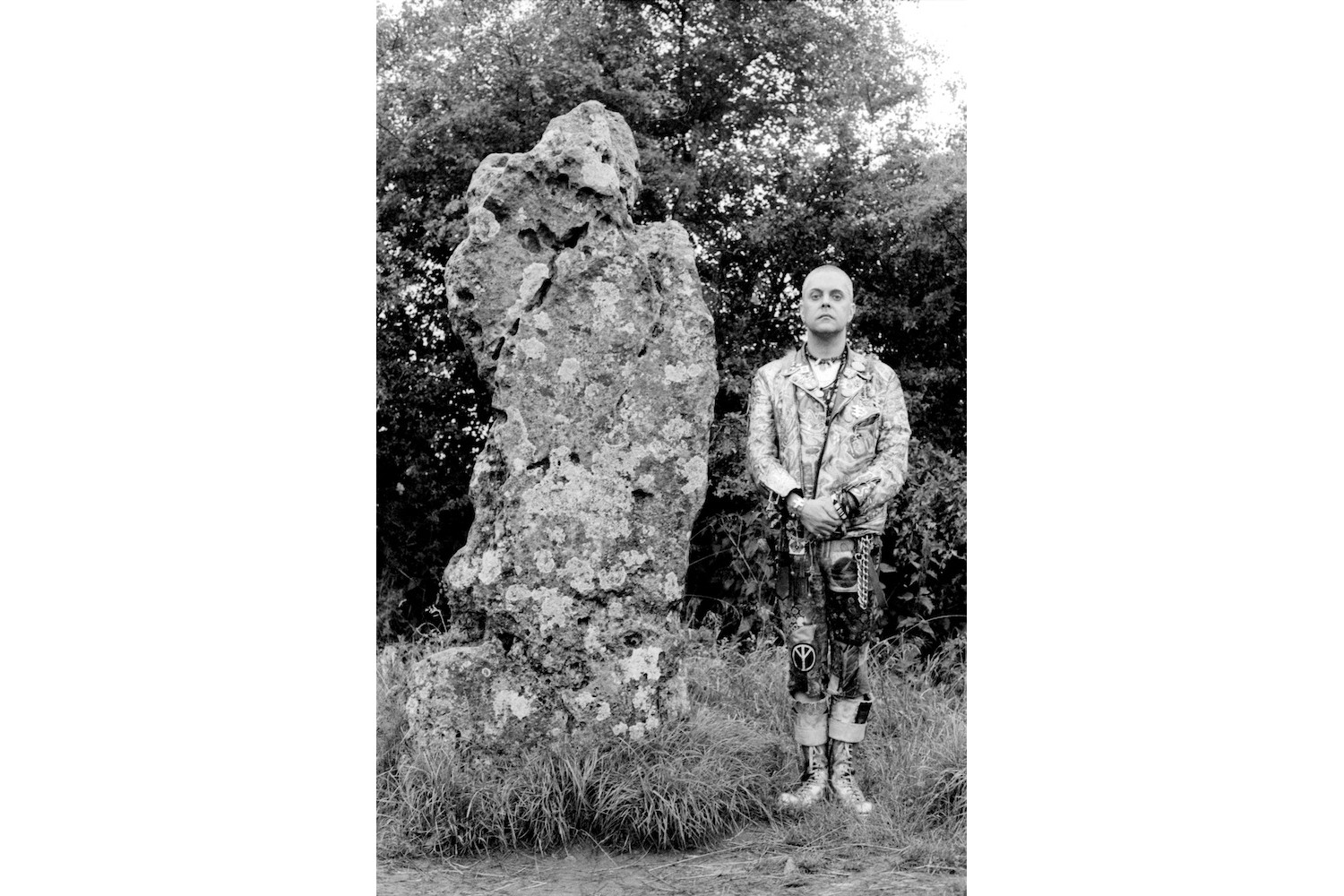

Gen’s agenda with TG — to reprogram the mind and free it from the far more menacing strictures of conventional culture — would soon give way to a more utopian, visionary impulse. When TG dissolved in 1981 amid the artist’s breakup with Fanni Tutti, Gen embarked on a new project, Thee Temple ov Psychik Youth (T.O.P.Y.), which s/he deemed a fellowship despite its deliberate adoption of cult-like principles. Based in Brighton, UK, T.O.P.Y had more than ten thousand members at its height in the late 1980s, and, as Dan Siepmann described it in PopMatters, “fashioned itself as a youth resistance bloc that deployed chaos magick against the myriad forces of societal control and conformity prophesied by Williams S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin.”

T.O.P.Y.’s musical platform, the band Psychic TV (1981–1999), and its antecedent PTV3 (2003–2020), fused video art, psychedelia, and occult rituals with a rotating lineup of collaborators. PTV’s sound as such varied from release to release, the psych pop of Godstar (1988) giving way to acid house albums like Towards Thee Infinite Beat (1990), and ambient spoken-word experiments evolving into recordings like Hell Is Invisible Heaven Is Her/e (2006), which P-Orridge dubbed “The Dark Side of the Moon for the twenty-first century.”

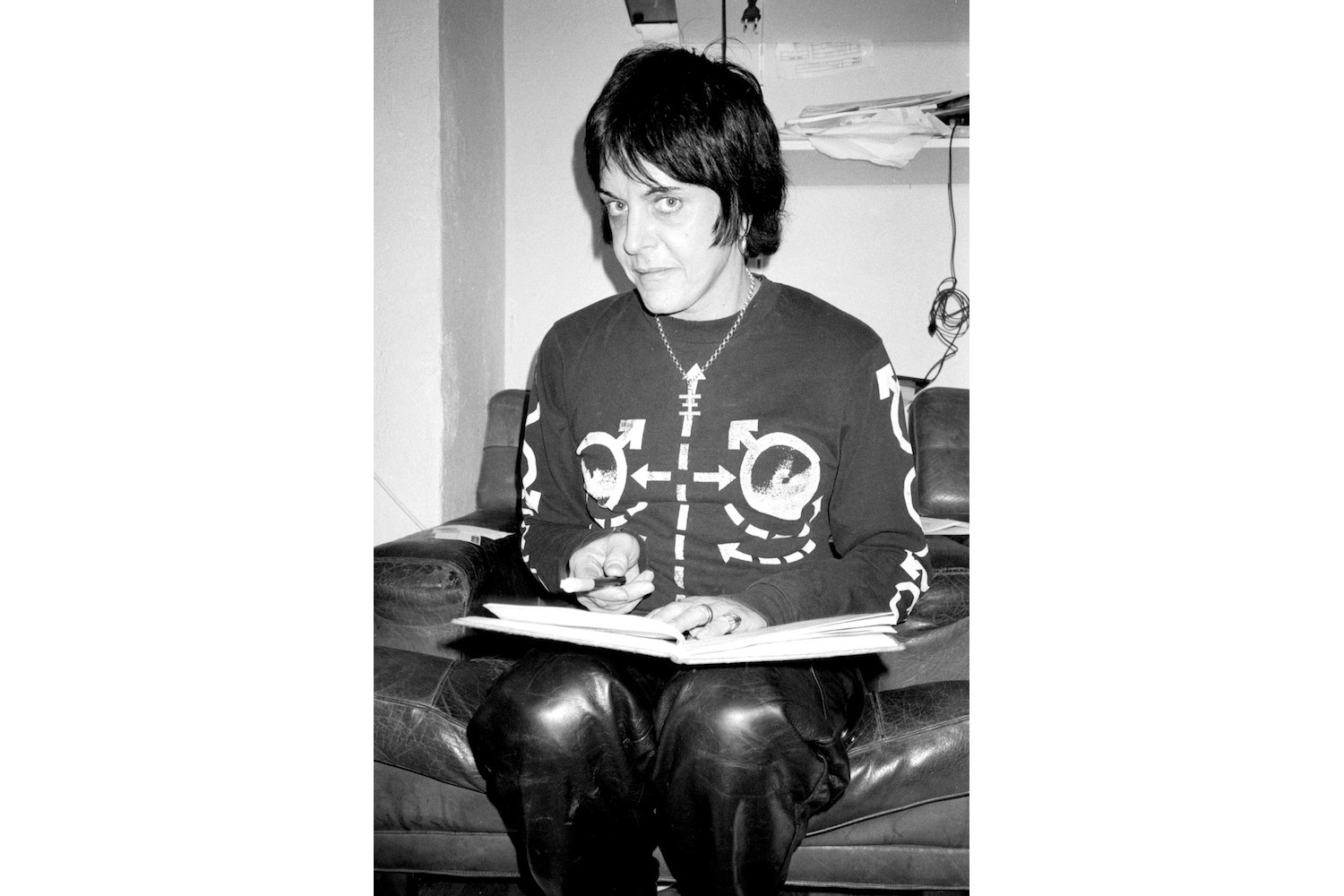

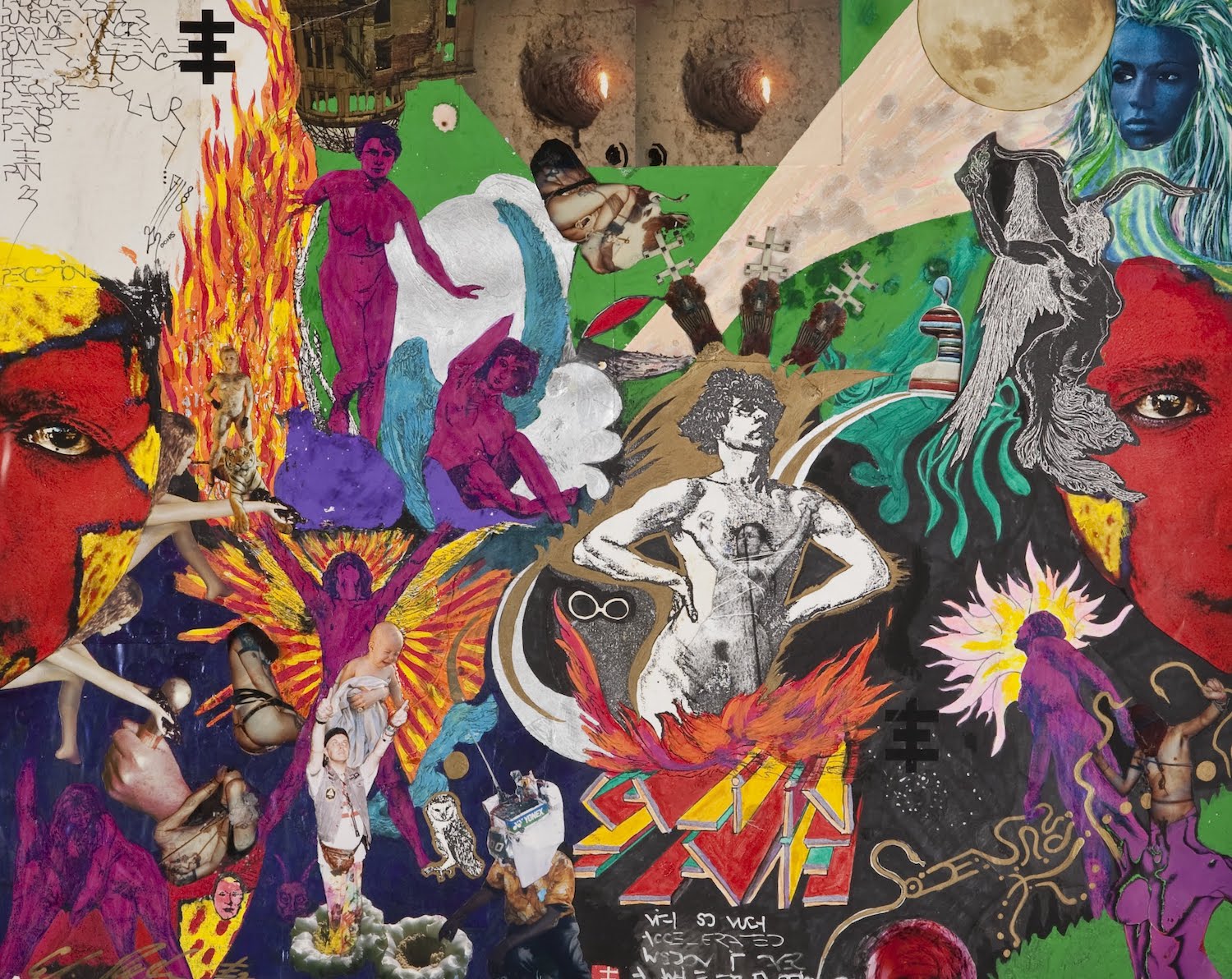

Thee Psychick Bible (1981–1991), which gathers a decade of writings and rituals by P-Orridge, remains T.O.P.Y.’s philosophical text, and the “psychic cross” its symbol and tool. The latter was used in PTV stage performances and in the artist’s collage sigils, in which body fluids, psychedelic geometries, photos of holy sites (most visited by the artist), and other ritual imagery appeared. The sigils in particular embodied P-Orridge’s view of the cut-up as a form of magic and sexuality as a form of divinity, and Gen never stopped making them.

Jaye’s contributions to PTV and all the pandrogyne work they created thereafter is often overlooked, yet it remains immeasurable. From their first meeting in early 1993 in the S/M dungeon where Lady Jaye worked, the two became inseparable. And as Gen has often acknowledged, without Jaye’s warrior-like commitment, s/he would never have realized he/r pandrogyne vision. In one of my favorite PTV3 tracks, “This is the Final War,” you can hear Jaye channeling and mirroring Gen’s prescient views on gender fluidity as she fiercely intones: “There’s no gender anymore”; “Join and love the man and woman inside you separated at birth”; Feel your heart, your heart is your art”; “Identity is your only possession, as a being possessed, repossess yourself”; “Identity is theft.”

After Jaye’s passing in 2007, Gen went on to make more art and music, to collaborate on more books and projects, even working on an (unfinished) autobiography at the very end, during breaks recovering from chemo. But what s/he achieved with Jaye, and their time together, was what s/he valued and cherished most. And though s/he officially died from leukemia, I think s/he was rescued by Jaye in the nick of time so s/he would not have to endure COVID’s plague-like devastation. As the rest of us contemplate a bleak future in its aftermath, I take solace in the knowledge the two are together again, and that Gen’s legacy lives on. Along with my now-sanctified Shango staff, it is full of revelations yet to be discovered and, if we pay close attention, signposts to help us find our way.