Like anything else, “Stinking Dawn” affects the way you see things as much as it reflects them, but it is rare for an exhibition to make you feel anxiety so deeply, for better or worse. For one thing, even if the artists don’t realize it, the very idea of the exhibition produces a kind of FOMO (“fear of missing out”) effect. The way the exhibition looks and feels is, meanwhile, typical of what I have already started calling the “New Apocalyptic Mode.”

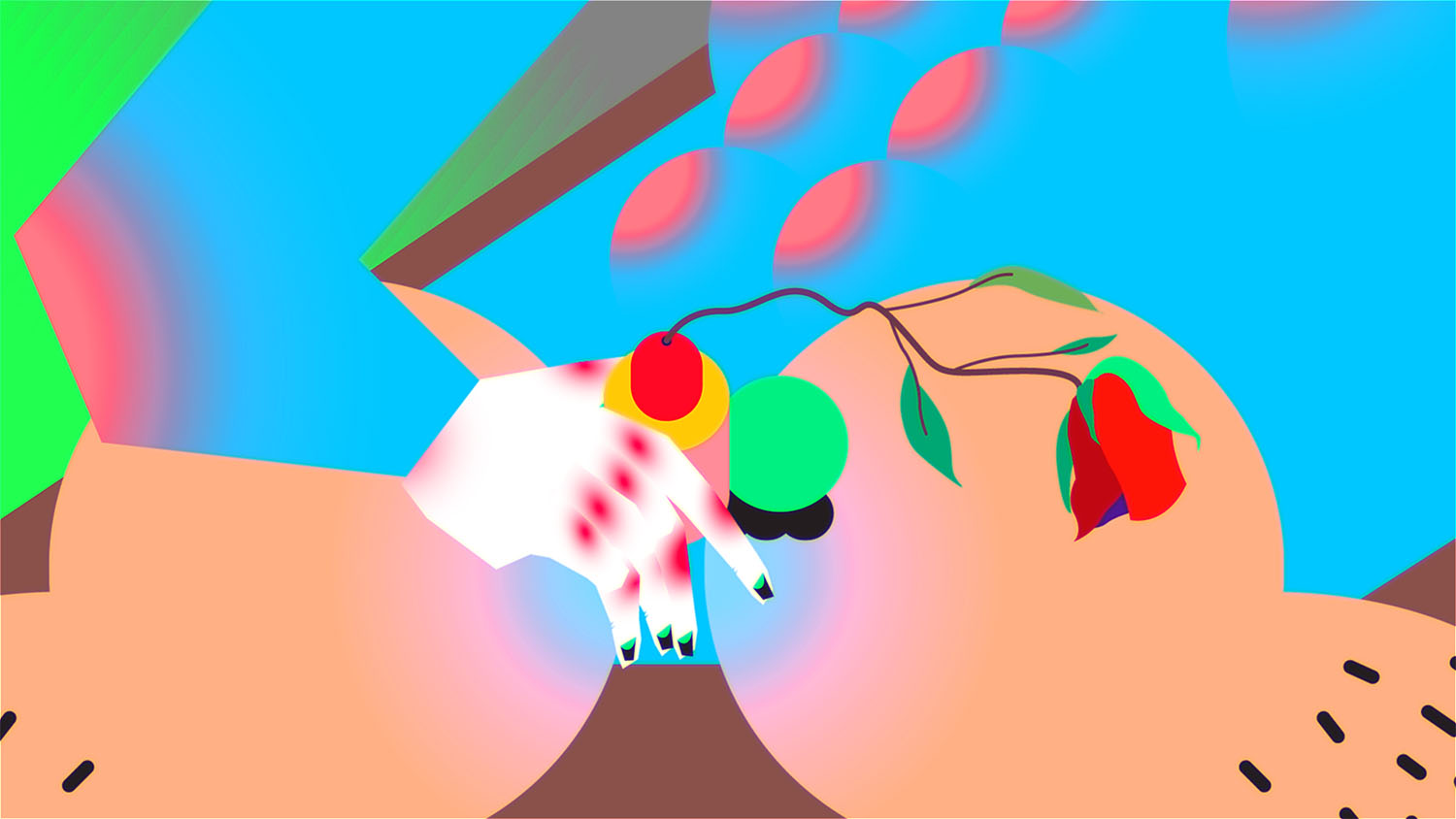

“Stinking Dawn” is, in part, the production process for a film written by Liam Gillick and developed, staged, and enacted by the zany relational-aesthetics foursome Gelitin. Gillick’s script, based on French philosopher Gilles Châtelet’s To Live and Think Like Pigs: The Incitement of Envy and Boredom in Market Democracies (1998), is a kind of anti-bildungsroman, a morality tale for the present age.

The narrative, following a basic trajectory taken from the “counter-enlightenment,” shows the descent of four privileged young men through various stages of enlightenment toward collapse and self-delusion in the face of oppression and political crisis. The problem is this: playing with reactionary thought is one thing, but flirting with political incorrectness by dressing up in grotesque “primitive” costumes, skirting the borders of blackface for the whole performance, is something else. It isn’t a good look.

During the shooting (from July 4 through 14), all visitors to “Stinking Dawn” were caught on camera as potential performers. The artists then moved to the studio for post-production, and the already-edited parts are now projected onto parts of the museum space. The film will eventually be premiered in autumn.

The problem is that if you did not take part in the initial process, you are left only with the “stage design.” This consists of polystyrene representations of broken colonnades, ruined amphitheaters, shattered nightclub interiors, and prisons. Phrases like “We are all fascist worms” are scrawled on the walls. It is difficult to know what to make of this unless you were there in the first place; you are left to rely on the explanation from the press release, which doesn’t tell you much.

Without seeing the film, “Stinking Dawn” is still visually striking, though. While many artists are making polite, small-scale renditions of “ruin porn” for commercial gallery spaces, this is a life-size approximation of a war-torn landscape where hope is not merely gone but can barely be recovered as a memory trace.