Bice Curiger’s “Illuminations” describes contemporary art as a recursive modernism that wraps pre- and post- together in one curatorial swoop. The result is a sometimes-confusing display of art as a historical field resembling a matryoshka doll that doesn’t quite fit together (Italy’s Tintoretto and Cattelan; Luigi Ghirri and Gabriel Kuri setting up Cyprien Gaillard; and David Goldblatt across from Haroon Mirza in star-shaped rooms designed by Monika Sosnowska). The Arsenale and Giardini exhibits presented a series of forced relations to art history and indefinite reflections of global art “as a process.” Both were a scattered mise en abyme that felt more shallow than intriguing (Cindy Sherman’s installation ended up a kind of biennial wallpaper that parodied her work instead of framing her ridiculous portrait subjects as believable).

Yet, a salient curatorial point – art as the creative vehicle behind community in general – did come through in specific works that were definitely illuminating.

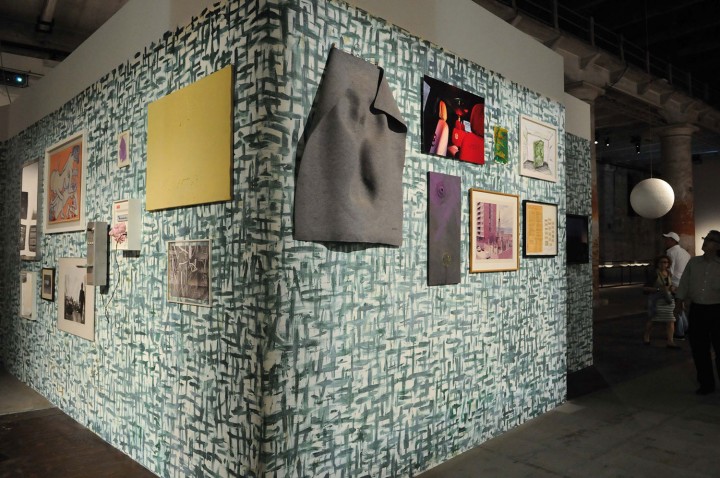

This was perhaps best demonstrated by Franz West’s understated studio-kitchen that affectionately contained other artists’ artworks hung on its walls. As straightforward readymade, the work reflected far less complicated things than splicing together anti-modernism and the Enlightenment: it was about the inevitable joining of domesticity and art, and the universal space of routine and convenience wherein an artist, like any person, cooks his meals and has a daily routine arranged at the core of his art studio and therefore practice.

There was a more orotund community on display, including a raucous rock band, that really epitomized how permeated by vague histories visual art feels and how the sense of the contemporary lives compulsively inside previous times. Also of Austrian origin, the collective Gelitin (who had a video included in West’s kitchen) “researched an oven that was used to melt glass in ancient times” and imported it in order to rehearse communal life, antiquity and temporary community for biennial visitors, as Curiger put it.

The collective seamlessly melded their material domain (essentially a pile of wood and an oven) with their community statement (nicely fused by electro-din) and this integration was their proprietary image. They were there to partake in the representation of their glass-burning troop and happily posed for group photos when they were not stoking the flames, dancing or chatting.

As people gathered to watch the caldrons and men in fireproof suits pour red-hot glass onto the lawn at the furthest end of the Arsenale campus beyond the Artiglierie, the remove from La Biennale felt like a flight back to ’50s Happenings. Out there with the tribe what joins present throwbacks with Modern or Enlightenment art is the pleasant omission of history and specificity altogether (and the familiar way in which it is unspecific). Gelitin was an ideal “illumination” because it was simple: it was hang-out art that was unchallenging to the initiate. Those who sat and partook shared a “community” displaced from the demands of the biennial. It was a shrewd blend of materials and immaterial labor (a list of which reads: “Installation, performance, music, love, fire, sweat” and a “glass-melting furnace built out of bricks and heated with wood”).

The photogenic party and impromptu performances, repeated daily fueled by beer and homemade wine, were unlike the time-based artwork in the Biennale (excluding perhaps Christian Marclay’s The Clock); it was an open-ended dissolve of the work of art and the work of viewing.

Gelitin, as temporary artisans heating the glass only to dump the lava in the yard also lived out a notion central to global art penned by Boris Groys (curator of this year’s Russian Pavilion). As Groys sees it, “the rejection of ‘non-alienated’ work has placed the post-Duchampian artist back in the position of using alienated, manual work to transfer certain material objects from the outside of art spaces to the inside, or vice versa. The pure immaterial creativity reveals itself here as pure fiction, as the old-fashioned, non-alienated artistic work is merely substituted by the alienated, manual work of transporting objects.” Groys’ assessment of the situation sounds a bit grim, but the realm of displacement and rejection he is describing is a very privileged brand of subculture. The successful recurrence of this privilege, its obsession, is a biennial’s lifeblood.

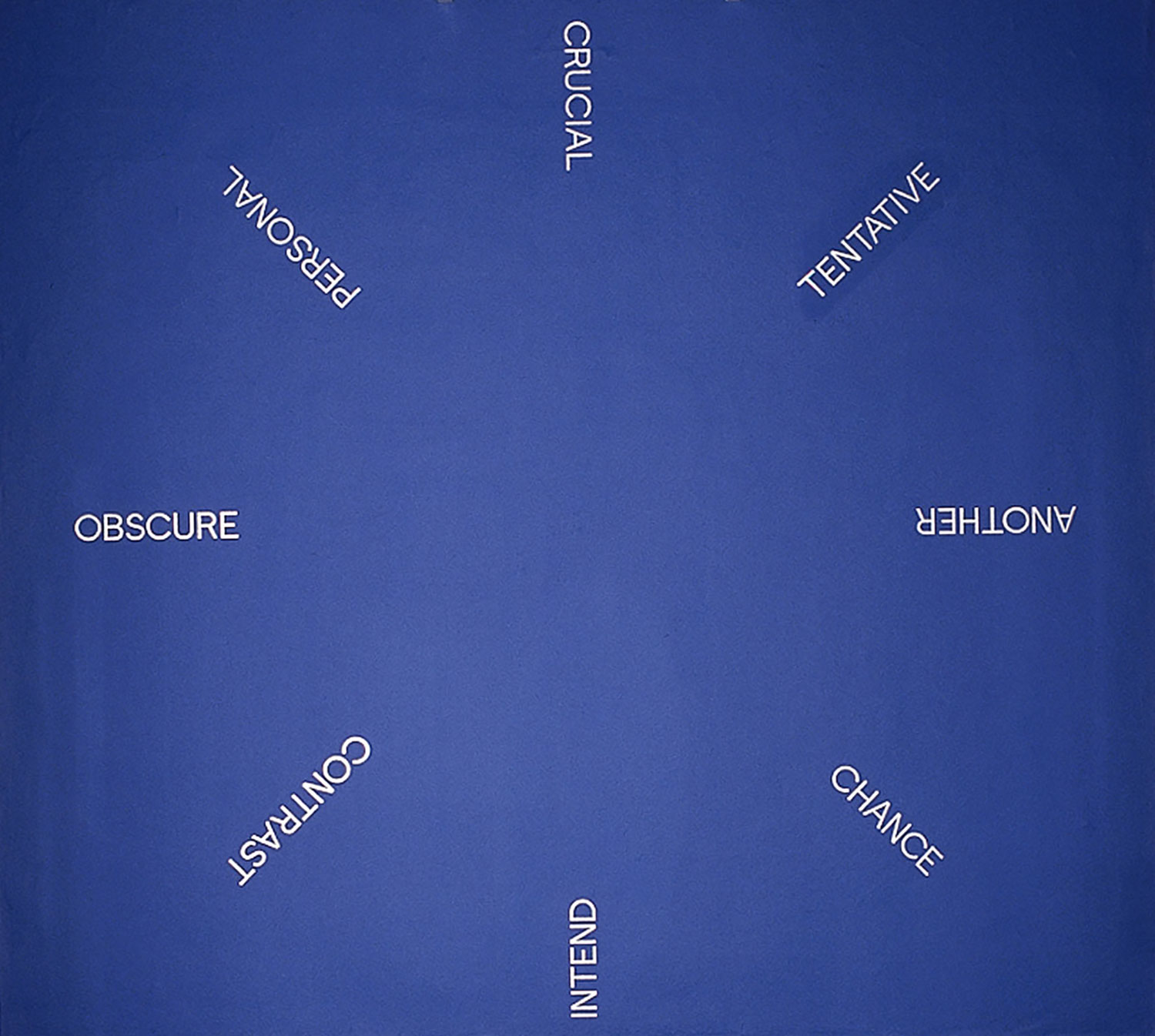

Gelitin’s oven, like their nudist antics and punk rock stagecraft, was a return; it didn’t matter to where or when exactly (the pretext of Venetian glasswork was adequate excuse to import art-rock-installation paratroopers Japanther, who are a studied form of New Wave anachronism in themselves). Sitting in the garden outside the Arsenale, which could have been any manicured environment anywhere in the world, watching the crowd gather as the noise and smoke increased at intervals, all that was crucial was the return of the past, any past, in many unspecified forms.