In 1972 the Pruitt–Igoe housing estate was blasted into rubble in St. Louis, Missouri. Also in 1972 the Swedish pop phenomenon ABBA came into being, although not yet under that name. Their first American single “People Need Love,” released by Playboy Records that year, was attributed to Björn and Benny (with Svenska Flicka [Swedish Girls]). And just as the Pruitt–Igoe took about half a decade to be erased from the face of the earth, ABBA did not form overnight. This event — the demolition, I mean — is widely considered the symbolic end to the modernist project of attempting to organize society according to totalizing utopian models. Less than twenty years before, the hope had been to relieve social problems by offering affordable housing in thirty-three International Style buildings designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki (who would subsequently design another emblem of collapsed order, New York’s World Trade Center), but by the late 1960s those hopes were considered to have irredeemably failed. Pruitt–Igoe had become a slum, and just like that modernism was over, giving way to the era of anything goes. But of course such an end, too, is contested, as modernism continues to convulse around the world. And though they have not released a new album since 1981’s The Visitors, ABBA never officially disbanded either, but have remained in a similarly undead state. Until now, that is.

This year Agnetha, Björn, Benny, and Anni-Frid will embark on a hologram tour of the world — a reunion of a kind never been seen before. The Abbatars, as they are called, will look exactly as their flesh counterparts did in 1979, and will even sing a couple of new songs. This futuristic striving toward a horizon where the spectacular meets the specter is more in line with ABBA’s ethos than many might assume. In 1977, 3.5 million people attempted to buy tickets for a performance at London’s Royal Albert Hall — enough to fill the venue more than five hundred times — about which one reviewer wrote: “ABBA performed slickly, but with zero personality coming across from a total of sixteen people on stage.” Agnetha was always the star of their music videos, but when the camera points at her, she aims her blank stare somewhere beyond us. ABBA were never really there, and precisely in that quality — the absence behind the smiles — lies their genius.

I realized this only when, early last spring, I heard the title track of The Visitors played for the first time. I was an extra in the Irish artist Doireann O’Malley’s film Prototypes, which she would exhibit at the Dublin City Gallery that summer. The final scene showed a number of people gathered around a bar. As we stood there holding pastel-colored drinks, spacey sounds tentatively built up before a deep female voice let out a wall of song: “I hear the doorbell ring and suddenly the panic takes me / The sound so ominously tearing through the silence.” What is this music? I

thought. 80s pop run through an existential distortion? I didn’t recognize it as ABBA, although it has their signature seriousness, something knowing: a pair of eyes that have seen the world, and an earnestness at odds with the upbeat chorus.

We shot the scene maybe ten times, always with the same song. I became familiar with it. It is both atypical and completely emblematic of ABBA’s output, a claim that I’ll extend to the rest of that record. This is when the Swedish quartet gave it all away, laid out what had been the more or less invisible core of their music all along: a special kind of sadness. I write this now because the relentlessness of the histrionic Mamma Mia! franchise has helped draw a cloud of silliness over the group’s legacy. And though there have been many satin onesies, ABBA is anything but silly.

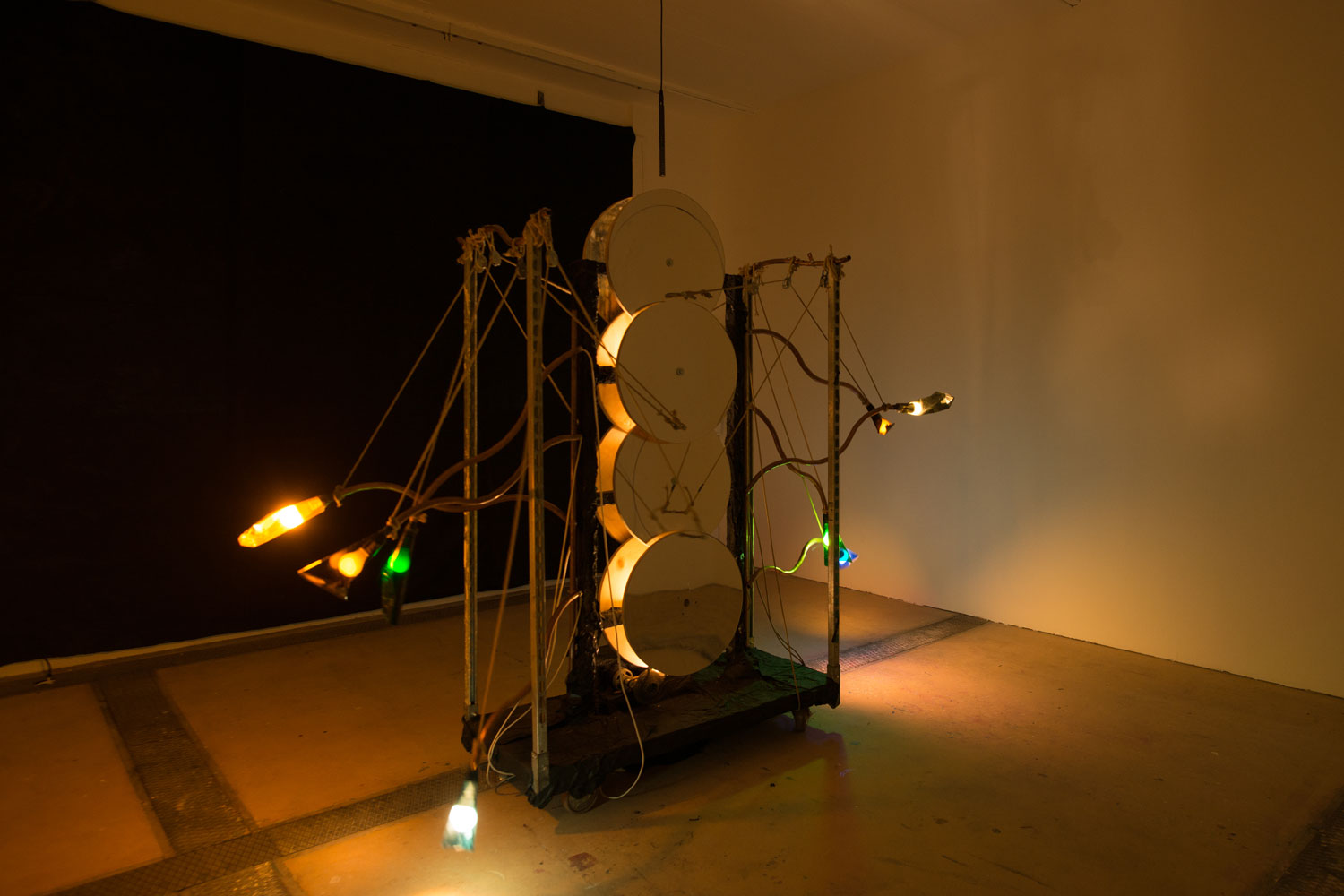

The Visitors, O’Malley correctly assessed, was made for that scene. The bar is chic and dim, a perfect square inside the Akademie der Künste, an exhibition complex in Berlin’s Hansaviertel, the neighbourhood that provides the setting for all of her two-part film. Construction of the area began in the 1950s as an ideological counterpoint to the monumental Stalinallee (now Karl Marx Allee) in the city’s East, showcasing the ability of Western architecture to organize freedom. A veritable wet dream of mid-century design — there are buildings by Alvar Aalto, Oscar Niemeyer, and Arne Jacobsen — its beauty is as subtle as it is complete. Akademie der Künste’s former president Klaus Staeck described its constellation of glass-encased courtyards and levitating staircases as a “spiritual and architectural anti-event,” while its architect Werner Düttmann called it an “unemotional box.” The architecture of this period was stylistically objective and methodological, a riposte to propaganda aesthetics, and an earnest attempt to help heal the societal trauma and literal ruination left by industrialization and war. It was not that these were unemotional times, but that loss was a given it made no sense to dwell on.

Similar to Düttmann’s architecture, ABBA’s music was always about keeping your chin up — who does that anymore? — and as such, inaugurated by the demolition of Pruitt–Igoe, ABBA is not the antithesis of the modernist paradigm but its swan song, its “Thank You For The Music.” The Hansaviertel is a tombstone for the same disappointed hopes that blasted bombs under the Missouri estate, and this is what resounds throughout ABBA’s oeuvre: the impossibility of utopia, and the sad beauty of mindless perseverance. Consider the fatigued homesickness of “Super Trouper,” the forceful embrace of fatalism in “Knowing Me Knowing You,” or the pleading possessiveness of “Lay All Your Love On Me.” And especially “Waterloo” and its blow-to-the-stomach pronouncement on love: “I was defeated, you won the war.” These songs are in turn desperate and delusional, but above all expertly crafted melodies. In early disco music, as it came out of black and queer communities in the US, pain was a friend you had to learn how to dance with. Even from within an apparently total heteronormative idyll, ABBA understood this, and what might look like “zero personality” should be read rather as a measure — heartbreaking, when you think about it — of necessary detachment.

To call ABBA queer would be a stretch. But to make the comparison at least invites a complication of what queer could mean: to inadvertently end up on the outside of … something. O’Malley’s Prototypes is about queerness and change, and the artist chose The Visitors, I imagine, because ABBA, too, embodies a prolonged moment of transition. In the film, characters are presented with the opportunity to pass through a mirror into an alternative world where gender does not exist. This is the question that lights up their faces when Anni-Frid begins to sing: “Would I do it?” There is no answer, but throughout the film we learn that struggling on the margins of established sex and gender categories, in the end, has made these characters who they are. The beauty of O’Malley’s gaze is that she dares look at the transitional not as a place of lack, or even necessarily transient, but rather as the site of especially valuable insights. Like the transitions between days — sunrises, sunsets — those who dare inhabit the neither–nor have a precious intensity. ABBA is steeped in this. The seventeen-year-old “Dancing Queen” having the time of her life is expressly not the woman singing about her. This “girl with a taste for the world” reappears in “Does Your Mother Know” and “Head Over Heels,” but is always observed from a position shifting between longing, judgment, and regret.

Whenever ABBA does sing in the first person, the point of view is that of an empty silhouette. Living in a house that is no longer there, after all, means not having anywhere to speak from except before and after. “The Day Before You Came” is a monotone masterpiece from The Visitors that chronicles the lonesome routine of a single woman in a repetitive meter culminating in the flat delivery of poignant truth: “It’s funny, but I had no sense of living without aim / the day before you came.” But what might have been the story of a loneliness relieved by the arrival of the dreamboat, we understand, in fact describes the loss of that someone, and subsequent return to life without aim, and to rain, and the other things that rhyme with “came.” As so often in ABBA, the narrator speaks in the future perfect tense; not in the moment, but with one foot in the door of what will have been. This is the restraint that reveals what is really at stake: everything.

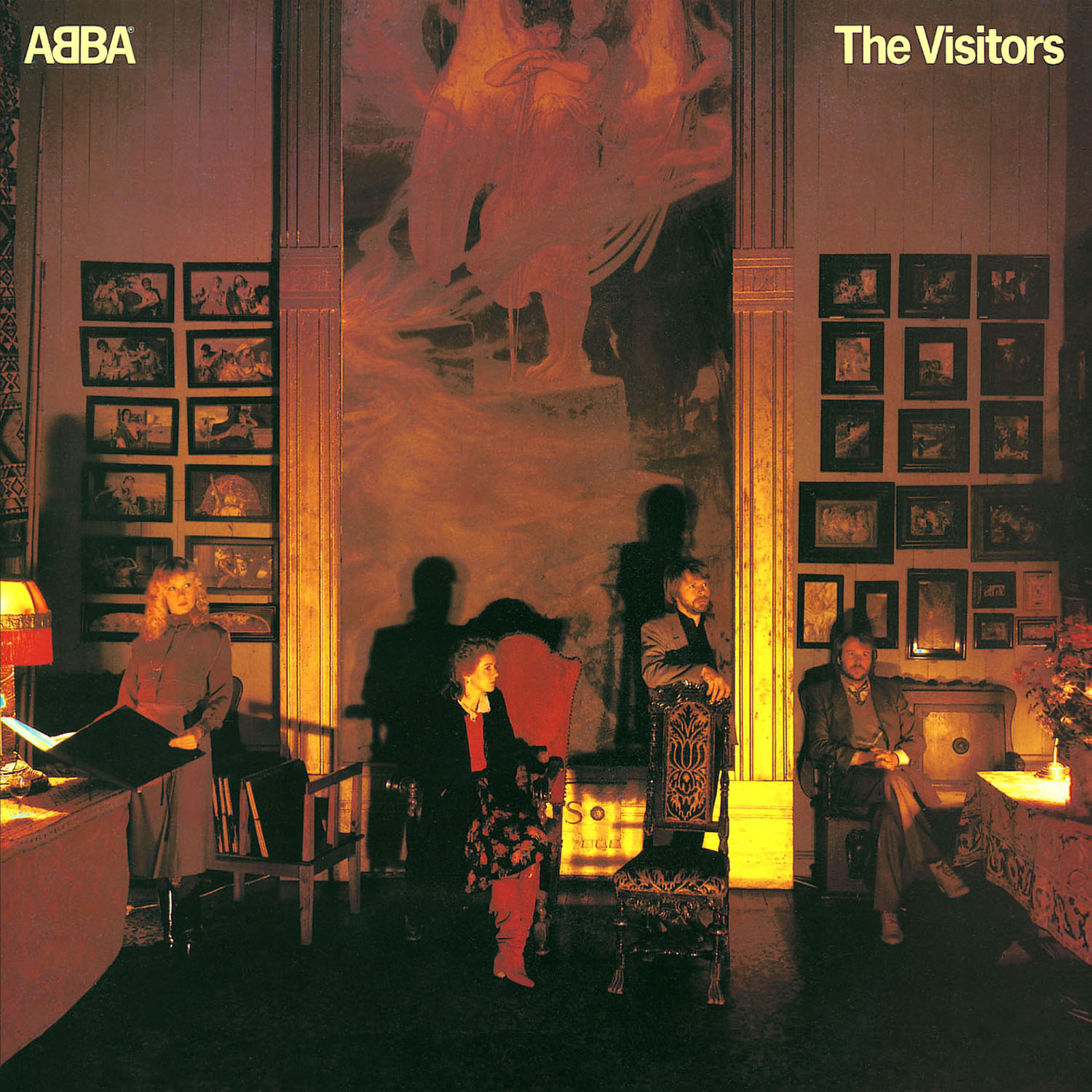

The cover of The Visitors is different from all the others. Most of them are symbolic in their own way. The group, whether in a limousine or a helicopter, is perpetually arriving at a New Year’s Eve party. But here, the lighting is dim, and the four band members are scattered across the atelier of the Swedish fin-de-siècle artist Julius Kronberg (1850–1921). Anni-Frid and Björn cast their solid shadows onto a tall slim canvas, Kronberg’s Eros (1905): a pale, graceful man wrapped in a mauve shroud, arms crossed and frowning at the wind. In his work we find something of the Viennese Secessionists or the British Pre-Raphaelites — Kronberg was a modernist insofar as the thickness of his classicism lets on that he understood the party to be ending. On the other side of the same threshold, ABBA’s claim to the modern manifests in their combined commitment to craftsmanship and dignified delusion; their blank stares and high chins; whatever it is that prevents the narrator of “The Day Before You Came” from caving under the burden of her sorrow. As evidenced also by the elegance of the Hansaviertel, a degree of self-deception is an essential part of the talent for living. To let go of that is to be prepared to die, a morbid predicament sometimes called postmodernism, or even modernism’s nascent state. And although any solid distinction between the two is almost always mute, the cultural production that exists under this contested term, ABBA included, has so much in common with that of Kronberg and his contemporaries: its greatest strength a self-conscious play with style; its Achilles’ heel an always imminent free fall into kitsch.

And where Kronberg indulged in sexy demigods and pastel-colored ombré, ABBA started appearing in flashes — I mean, actually being there — too grand, too sad, too beautiful.

In “I Let the Music Speak,” another track from The Visitors, the lyrics declare the commencement of a time of “no restraint,” of letting “the feeling take over.” And then Anni-Frid’s voice truly soars: like a butterfly that spreads its wings only in the evening of its life, the music flies off into unchecked sentimentalism, the unambiguous appeal of grand emotion, Muriel’s Wedding and Mamma Mia!, where culture goes to take its final breaths. To go on to make musicals for the next three decades is the best and only thing Björn and Benny could have done. And likewise, to relaunch ABBA as holograms might be the only way to reinstall some of the heartfelt absence that always made their name. “Sometimes I wish that I could freeze the picture / And save it from the funny tricks of time,” sang ABBA at their saddest in “Slipping Through My Fingers.” To have that sung by a hologram, I think, will nail the post- to modern for good.