Massimiliano Gioni: You worked with Helmut Berger and Carlo di Palma, John Maybury and Marisa Berenson: an army of stars and famous directors, all performing for your videos, often caught up in twisted roles… At the 2001 Venice Biennale, for example, you asked Veruschka, an icon of the ’60s and ’70s, to sit on a sofa for three days while embroidering an old portrait of hers. How do you convince these divas to work for you?

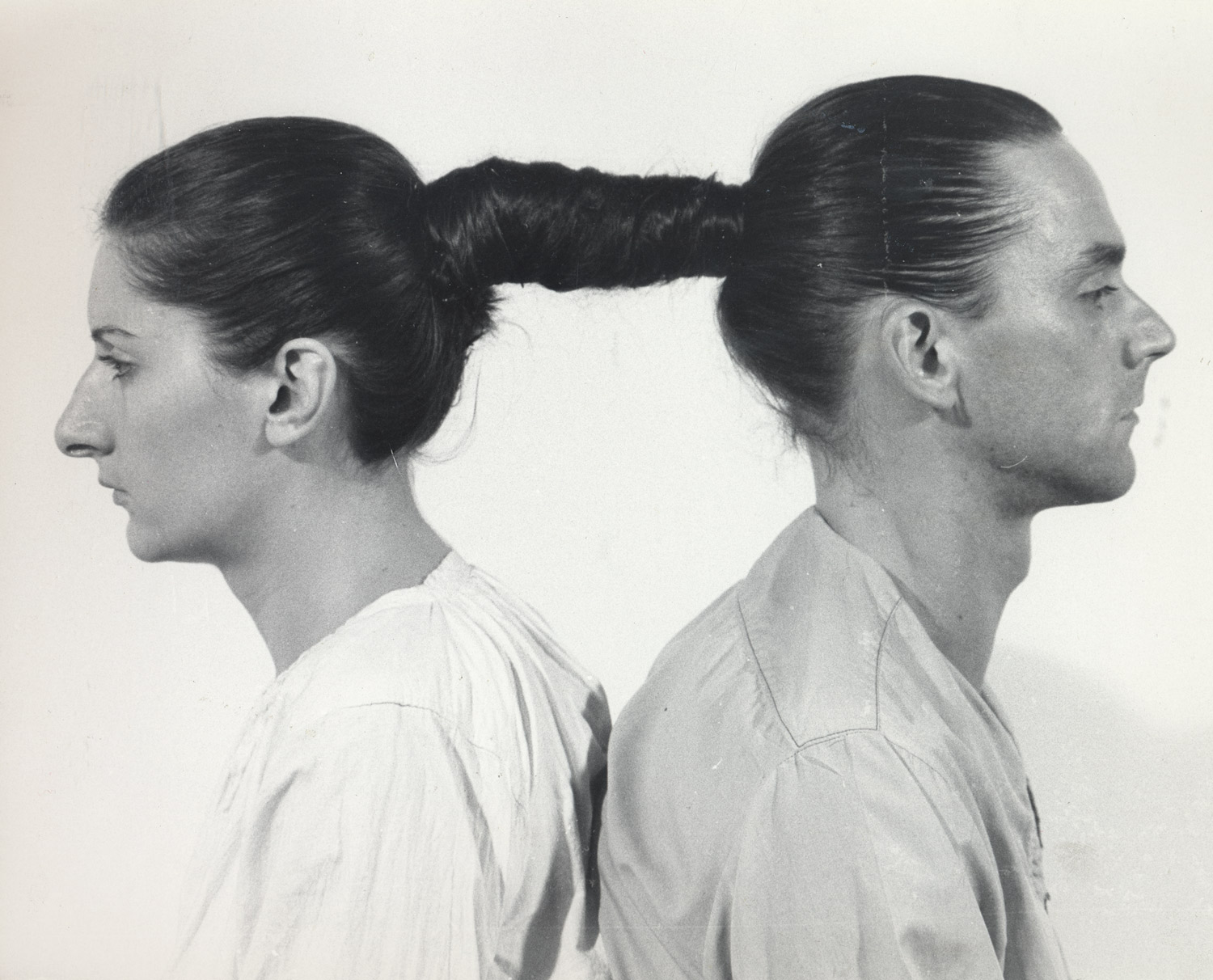

Francesco Vezzoli: It’s always quite risky. In the past I’ve approached some people without warning. Like with Carlo di Palma, I surprised him in a restaurant. I went up to him and said: “Hello, I’m Francesco Vezzoli, I love everything you’ve done. I would like to do something with you,” and it worked. For Helmut Berger, I got his phone number off someone and I just called. We talked and then I showed up at his house with five hundred white lilies. He threw them in the bath and asked: “What the hell do you want from me?” and I explained that I had gotten Marisa Berenson to play Edith Piaf, and then maybe, Mr. Berger, what about doing a video with me? You could embroider the face of Querelle de Brest, and then kiss me while we’re playing a scene from Dynasty; wouldn’t it be fun? And again it worked. With Veruschka, it was quite different. I invited her to watch my videos and when we got out of the screening room, she just said: “I’d do anything you want.” So she agreed to do the performance in Venice, and she also agreed to do a remake of a famous cover of Stern Magazine, which portrayed her at the peak of her career in 1969. Thirty years later we got the same photographer, Gianpaolo Barbieri, the same make up artist, the same hair dresser, and the same Valentino dress, and we restaged the image.

Helena Kontova: How do you choose who to work with?

FV: Helmut Berger was the climax of my obsession for Luchino Visconti. With Veruschka it was quite different. I chose her mostly because of a scene in Antonioni’s Blow Up, which is an incredible movie: it’s the film that establishes the notion of the fashion world. There is this super-cool photographer, a kind of David Bailey, and then there is the supermodel, Veruschka, and there is this beautiful sequence when she is making love with the camera. Next thing you know, she says: “I have to go. I must be in Paris tonight,” or something like that, something really glamorous… I wanted to go back to that archetypal image of luxury. And she’s the first diva of the fashion world, the first person that changed her life into a trademark.

HK: How did she react? It must be hard to face your own image thirty years later, especially if your name is so clearly associated with an ideal of beauty.

FV: She took the whole project with a great sense of humor. After all, she has no problem admitting that Veruschka is nothing but a fictional character, a brand. She is a self-made diva. She probably thought of the performance in Venice as a sequel to her fictional past. Besides, Veruschka has been through everything: the war and the Nazis attacking her house when she was a baby, and then the fashion world, the parties, the richest men in the world all around her… She can’t be impressed by anything. Of course, there was a form of violence in my work, it was like an inverted version of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

HK: Why do you always work with people who are entering the realm of oblivion?

FV: If I were to answer like Proust, I would say it’s simply because when I was a kid, I would spend the summer with two grandmothers, two aunts and a couple of their octogenarian friends… My sentimental education is based on those figures that somehow had entered their own personal Sunset Boulevard. I love people who have many stories to tell: I’m attracted by the stars who have survived celebrity. We all want our slice of history, even if it’s reflected in someone else’s eyes.

HK: Do you think there is also a sort of revival of that world?

FV: I don’t know, but sure enough if a photographer like Steven Meisel is quoting those images, then it means we can also go back to the original. I think there is something in the air, like a desire for a new sense of luxury.

MG: Where do you think it comes from?

FV: Maybe it has something to do with the fact that that world is gone, lost forever. When Marisa Berenson entered a room, people would clap: she was so beautiful it was unbearable…

MG: So it’s a form of nostalgia?

FV: Definitely. We miss the enthusiasm of those days. Those characters have founded the whole language of fashion and desire.

MG: Would you say your work is about rediscovering that world?

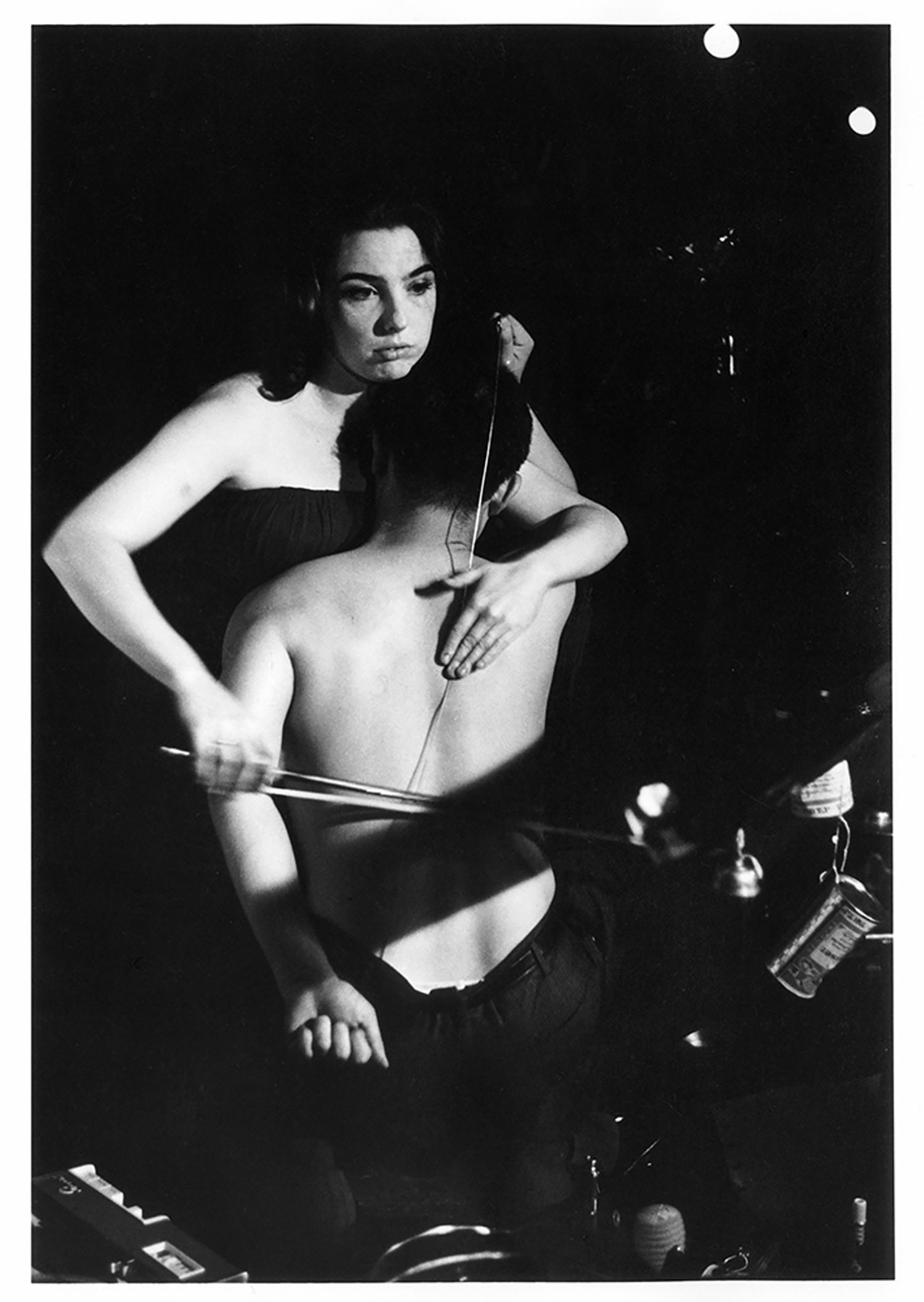

FV: I’m trying to appropriate mythologies and fetishes. I’m working on a tradition I never experienced directly: I never saw a movie by Luchino Visconti at the cinema, I was too young. I never saw a cover of Veruschka, I was a baby. So you have to restage your memory, which makes everything much more intense. It’s all a matter of exposing yourself, restaging yourself, appearing next to your heroes, even when your ideal of beauty is Donna Summer and Barbra Streisand on the cover of the No More Tears album. And then, of course, there is the tradition of art and artists, that you have to reappropriate and reframe. When I thought of Veruschka at the Venice Biennale, I was also thinking of Gino De Dominicis exhibiting a live person affected by Down’s syndrome or Marina Abramovic polishing a pile of bones. Even the idea of using performance as a medium was a sort of nostalgic operation.

MG: So, what’s nostalgia for you?

FV: Maybe it’s an antidote to speed. After all, embroidering is a technique deeply connected to memory.

HK: But embroidery is an activity traditionally considered feminine…

FV: Women are embroiderers almost by definition: they are the depositories of a world of sentiments and feelings that get diluted in embroidery. There is a lot of pain in embroidery: Penelope embroidered while waiting for Ulysses. And then there are the snobs: Valentino, Edward VIII and Wally Simpson all embroidered. In the history of art, on the other hand, you come across a whole series of noble embroiderers, often married to quite obsessive people: Josef Albers’s wife, Sonia Delaunay, Alberto Savinio’s wife…

HK: How long do you spend on embroidery?

FV: Three hours a day, more or less.

MG: Have you always embroidered?

FV: My first works were embroideries, and that’s where everything began. I was in London studying Fine Arts and at a certain point they say: “You gotta come up with something.” I hated being at college, and embroidery allowed me to be alone. It wasn’t a stylistic choice at first. It was a way to be left in peace.

HK: In all your work there seems to be a red thread that ties together cinema and embroidery. What is the relationship between these two worlds?

FV: My videos are a kind of encyclopedic parallel to the history of cinema: you just have to do a little research into the private lives of actors and stars and you realize immediately that embroidery is the private counterpart to the star system. Many stars have found a meditative space in embroidery. Silvana Mangano, the greatest Italian diva, embroidered monotone carpets; it is as though the obsessive action of embroidering was enough for her, she didn’t feel the need to draw anything.

MG: Embroidery is also a typically gay practice: are you interested in this aspect?

FV: Goodness, no. To me embroidery is above all an obsession: on the one hand there is the maniacal portrait of embroidering stars, on the other there is this attempt to compose a history of cinema through embroidery.

MG: And then there is the obsessive fan who persecutes the star.

FV: I’m a fan that asks for a cameo performance instead of an autograph.

MG: But you also parody the social climber…

FV: I never considered my videos as an excuse to make friends with some diva. It remains a discourse about art; you look around and ask what’s missing. It seemed to me that Helmut Berger or Veruschka were missing: in all the shows I went to see I felt that there was no trace of melodrama or feelings. I wanted to create something that contained the visual richness of an opera, something stuffed with quotations, loaded with references and details. It is also a way of being more sincere: more sincere with myself because I grew up in a world of grandmothers with puffed-up hair, and more true to my environment, because in all the magazines you only hear about luxury, but for some reason when you enter a gallery there is no trace of this opulence that permeates our imagination.

HK: Speaking of luxury, who is your favorite designer?

FV: I am absolutely devoted to Yves Saint Laurent, and then of course there are Capucci, Fendi and Valentino, who have made costumes for my videos. But in the hands of Yves Saint Laurent, purple, red and orange become something so incredible it sends you into raptures. Yves Saint Laurent is a genius, a professor whose energy and pain are unique. If I could be reborn, I would like to be reincarnated as Yves Saint Laurent.

HK: When you meet your divas, how do you feel? Intimidated, nervous, curious?

FV: Always curious, not intimidated, because I’m an outsider anyway. I’m not interested in living that life. I represent it, but I don’t long for it, simply because that world is gone forever. My work remains a study, a peek from behind the door. Maybe for a moment you seem to be living a dream. But it is a dream that must be very short if you want it to be really intense. And it is so much stronger if you manage to maintain a certain distance. Then, of course, there are these moments of social weakness that hit even the most serious and powerful people: when everyone turns around to look at the diva, and they start smiling at her, simply because she is so beautiful…

HK: What would you like people to say about your work?

FV: If you could use all the right words in all the right places, I would say that my work is a study of the weaknesses of a provincial fag, who grows up watching Visconti’s films on TV, and tries to learn something about antiques and art history, while transforming his solitude and pain into a magnificent obsession.