In 1993, the world was not so much different than today. In the Balkans people were killing each other and dying like flies and mosquitos. The art world was trying, as usual, to be a parody of the United Nations, who, by the way, were witnessing genocides and massacres with diplomatic aloofness. Amid all this chaos, the 45th Venice Biennale unfolded, and Aperto ’93 — the last of the Apertos — marked a historical event at the dawn of what we know now as globalization and of that horrendous term that is “curatorial practice.” Political correctness had not yet become an issue, gender and race were far from becoming the essential part of the curatorial “discourse.”

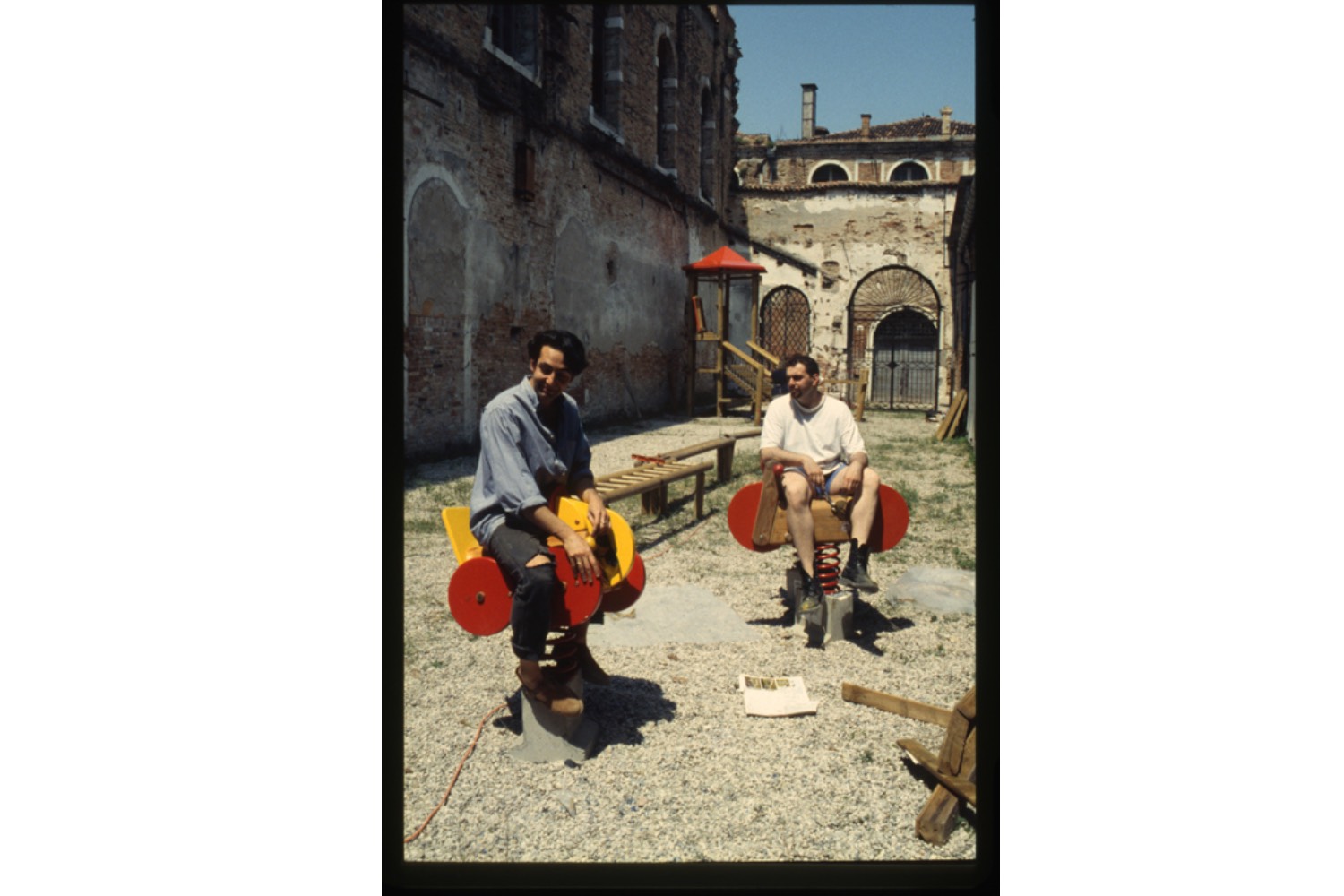

We were superficial, free, and poor. It was my first real curatorial engagement, and, under the metaphysical vision of Helena Kontova, I found myself mediating the different and relentless complaints of all the other curators and artists. Italy was in the middle of the infamous Mani Pulite investigation, plagued by bribery and scandal, but Venice was a “clean” land. Achille Bonito Oliva, the director of the entire Biennale, wandered around shirtless, Mussolini-style, as if the Giardini were a wheat field to be harvested. We were almost young — thirty-eight or something — and skinny, on the edge of emaciation. We were eating but maybe not drinking enough.

My section was titled “The Mere Interchange.” Why? No idea. The artists invited were few, but the stars of the group of artists I selected were Jessica Diamond — one of the most annoying individuals I ever met in the course of my career — and Carter Kustera — a sweet guy, really nice, Canadian, I believe — who I met again few years ago, fixing the floor of a Mexican restaurant in the East Village. Names in the art world are written in pencil. The rising emperor of that era was Thomas Krens, director of the Guggenheim Museum. Like Carter Kustera, the new generations have no idea who he is or was. Matthew Barney, one of the artists invited and already celebrated at Documenta 9 in 1992, was on his knees drilling holes in the landmark floor of the Corderie. Nowadays, any given unknown artist will demand two assistants to perform the job.

Charles Ray brought his 7.5-meter white steel cube, oblivious to the fact that Venice was built on stilts over water. He insisted on moving the cube, replacing Gabriel Orozco’s Empty Shoe Box (1993), but the operation would have implied the collapse of the ground, risking the loss of a few devoted installers. Eventually, he agreed to move his work, pyramid-style, just a couple of meters, tipping some cursing workers at night. He was unhappy, but at that time nobody cared since nobody was happy. But the most unhappy person I remember was an American artist — I forgot the name — who was looking for her work. She eventually found out not only that the work was not there but that we forgot to follow up with her invitation to the show. She stood incredulous in front of Rudolf Stingel’s imposing red carpet wall and Maurizio Cattelan’s space, which he had leased to a perfume company. At the same time, a powerful yet completely forgotten art consultant of the time, Thea Westreich, was passing under Cattelan’s banner commenting, “Boring… already done.” Perhaps it was boring, but nobody had ever done something like that before.

It was the beginning. The last Aperto was paradoxically the beginning for me and many of my future colleagues. However, at the same time, it was also a kind of Sunset Boulevard for father/master curator figures like Bonito Oliva and many of his male peers. In 1993, the art world imploded and exploded at the same time. Possible and impossible: this is what Aperto 93 was and still is.