I aspire to making art objects and collages that are like really good music that you keep listening to, keep generating, you never fully get,” says Nathaniel Mellors, as I sit in his studio on a blazing hot day in mid-June. I’m at the beginning of a tour of studio visits with some of London’s most exciting rising (and in some cases, risen) art stars, where I’m trying to come to grips with what it is to work as an artist in this city, with its diverse but strongly commercial contemporary art scene. In front of me is a half-completed work, made from a box with mud piled on one corner and a wooden arm protruding. And behind me sits a stuffed body stocking, soaked in fake blood, a relic of Mellors’ Hateball installation. It feels like a good start.

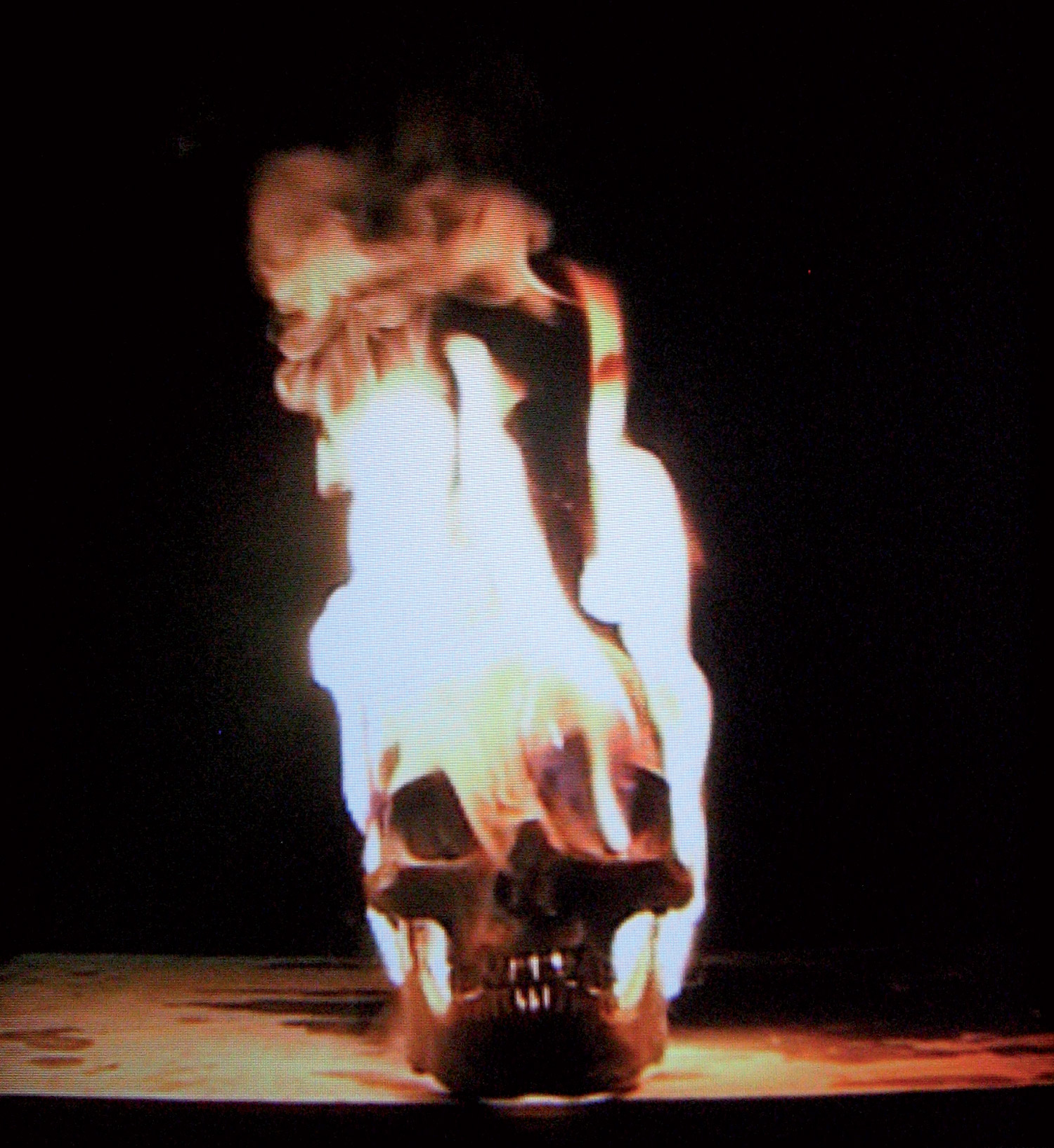

Hateball showed at Alison Jacques Gallery in February this year, and was the culmination of two years of work for the artist, beginning with his “Profondo Viola” show at Matt’s Gallery in 2004. The installation is typical of his work, combining narratives and formal art practices with offbeat and absurd qualities designed to gently but deliberately disconcert the viewer. “There’s an immersive quality to installations, you’re completely within something,” he explains. “But there are puncturing devices designated to unsettle that, which create the sense of awareness that you’re inside and outside something at the same time. My work is constantly throwing off different frequencies, dissonant harmonies, things that are technically wrong but can be absolutely right.”

Mellors’ studio is housed in deepest Hackney, East London, currently the most fashionable spot to work as an artist, as it is one of the few places left where you can find big, and relatively cheap, spaces. The city’s art scene has moved with the artists, with a multitude of small commercial galleries springing up around nearby Bethnal Green in recent years. One particular road, Vyner Street, is positively bulging with art, with gallerists including David Risley, Fred Mann and Stuart Shave’s Modern Art all residing there. In amongst this commercial atmosphere lies Olivia Plender’s studio, a space she shares with an architect and a designer, and which also houses Canal, an independent space for talks, film screenings and events, which Plender runs with six others. Acknowledging that she is “not a big participator in the commercial art scene,” Plender has so far resisted the overture of a commercial space, and sees Canal as a chance to offer another form of conversation and criticality, particularly encouraging interactions between artists of different generations, as well as between artists and practitioners in different fields, such as film and design. An adept multitasker, Plender combines co-curating Canal with her work as an editor for Untitled magazine and her own art practice, which has seen her take part in Beck’s Futures and the Tate Triennial this year. Currently working on a publication for Book Works about the Modern Spiritualist movement, she sees these disparate interests as a means of feeding ideas and inspiration into her art, and acknowledges that the London art world has become more open to diverse practice. “Editing a magazine and being an artist, people thought you can’t do that, you have to choose, but they accept this more now,” she says.

Joining Plender in the Beck’s Futures exhibition this year were two of her friends, Pablo Bronstein and Seb Patane, and the trio acknowledge that being in it together made the competitive atmosphere of the show, largely whipped up by the media, easier to bear. Both Bronstein and Patane work at home, rather than in a separate studio space, Bronstein round the corner from Plender on Columbia Road, while Patane is over the river in Vauxhall. This home-practice is for both partly financial, with the squeeze on artists in London more apparent than ever. Yet both artists also agree that they prefer this style of working. “I like having my things around me and being in my own world,” explains Bronstein. It has been a busy year for Bronstein, who alongside the Beck’s show presented a performance at Tate Triennial and also held his debut solo show at Herald St gallery, all within a year of graduating from the MA fine art course at Goldsmiths. When I visit, his studio-cum-bedroom is packed with piles of paper on which he is printing a book edition for the independent publishers book fair Publish and Be Damned, as well as stacks of the antique frames that he uses to exhibit his fictional architectural drawings. There is no foreseeable let up for the artist, who is about to embark on a six-month residency in Munich, while also producing performance pieces to take place in Turin and Cincinnati, and designing “some form of poultry shed” for Grizedale Arts in the Lake District of Great Britain. In addition, he is also preparing a minibus tour of postmodern London architecture to take place as part of this year’s Frieze Art Fair, with which he aims to “rescue these buildings from obscurity or unfashionability and to contextualize the Frieze fair within a recent cultural history instigated during Thatcherism in the 1980s.”

Down south, Patane is similarly hard at work on his first solo show at Maureen Paley gallery, which takes place in September. Patane has gained recognition particularly for his unnerving drawings, which distort or disguise appropriated imagery to emphasize a sense of the preternatural. “I’m interested in bringing figurative stuff into abstraction,” he explains. “There are ideas of the otherworldly or the repressed, they trigger ideas of the uncanny. It’s a way of engaging with the original image but also challenging canonic ideas of portraiture.” Alongside the drawings, Patane’s art also encompasses photographs, sound works and performative elements, and draws on a similarly varied range of influences, from electronic and industrial music to photographs found in magazines or at flea markets. “Usually something will catch my attention and I’ll start researching around it,” he says. He expects the new show to continue this diverse practice, but is aware that it will keep changing until he can begin working in the gallery itself. “I work on everything at the same time and somehow things connect,” he says. “The space influences what you do. I leave it to chance, I do a lot of editing at the end. You surprise yourself at the end.”

I head to nearby Camberwell to visit Martin Westwood’s studio. Westwood is fresh from Art Basel, where he exhibited in the Art Statements section of the fair. His intriguing installations and sculptures, which investigate the increasing influence of economics on our emotional lives, seem an apt counterpoint to the charged commercialism of the art fair. “What interests me is the commodification of our internal space,” he explains as we look through images of the work. “It can be viewed more and more through a commercial lens. Even in romantic relationships a method of economic exchange occurs.” Westwood is now slowly starting preparations for his forthcoming solo show at The Approach, which will take place in February. At this stage, this means going over former ideas to see where they will next take him. “I’m always throwing out things that were maybe useful,” he says. “Every piece of work you’ve made, it could have gone in another twenty directions. I’m hoping the works will surprise me on the journey of making them.”

Carey Young, who works from her home in Islington, in the north of the city, also examines the pervading influence of the corporate world on our lives. Young’s work is informed by her previous experiences as a part-time employee, first of a multinational IT consultancy and then of a leftist economic think tank. “Each day in the office I would find or overhear something which later became material for my artistic work,” she reveals. “I’m interested in the way corporations influence our relationships and identity, and in exploring the implications of the corporate hunger for political influence, creativity and subversion.” Young often creates site-orientated work that addresses political issues related to the city or institution she is exhibiting in, which in the past has seen her manifest ideas as diverse as a conflict resolution stand in a Budapest market or a legally-binding space in New York’s Paula Cooper Gallery, which, when stood in, became a declaration that the US constitution did not apply to you. Her work involves regular interactions with professionals that fall outside the art world sphere, including lawyers and technologists, and Young similarly likes to push at the boundaries of typical art categories, such as performance or portraiture, as was evident in her work for the IBID Projects booth at last year’s Zoo Art Fair, an installation in which viewers could telephone a call center worker. “The piece is a telephonic portrait of someone whose identity is normally denied to us,” she explains. “But it also offers an expose of the call center industry and a meditation on the commercialization of human relationships.”

Also skilled at negotiating contributions to his work from experts in other fields is Ryan Gander, whose idea-based practice saw him working with Italian lawyers, horticulturalists, and the seven-year-old son of the gallery caretaker for a recent show at the remade Pavillion de l’Esprit Nouveau in Bologna. “Sometimes I don’t say I’m making art, as that can sometimes hinder things,” he admits when discussing the collaborative experience. Gander works out of a highly organized, but frenetic studio space in Hoxton, with the help of two assistants. Demand for his work is at a high, but he has decided that from January next year he is taking a year’s sabbatical, “because I want to go to the library a bit more,” and so he can explore more experimental work. “There’s too much to do with commercial shows, I’d rather be making bigger work, more ambitious work, rather than just making ‘things,’” he says. There is plenty to keep him occupied until then though, with upcoming shows in Milan, Miami and Los Angeles as well as the first of two shows that will bookend his year off, both at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Alongside this, he is also curating a year-long program of shows at Associates, a new not-for-profit gallery which will take up residence in the original Store space after it moves down the road this summer. Associates will open in late September with Matthew Smith. However, Gander is clear about his role within this enterprise. “I don’t have any aspirations to be a curator or gallerist or anything,” he says firmly. “There’s loads of really good artists in England, but because they’re not in London they never meet anyone and never get shows… it’s giving them the chance to do whatever they want, but without any pressure.”

Around the corner from Gander’s studio is where artist Marine Hugonnier is based, working from her flat within the Barbican. The area’s concrete design exudes a peaceful calm, and she admits that she would be reluctant to live anywhere else in the city. “I’ve been working for four years here, and I wonder if this architecture has had an influence on my work,” she says. “The Barbican is kind of like a city within a city, it’s a super-urban environment, but there’s no street noise.” When I visit, she is in the throes of an exhibition at Max Wigram’s New Bond Street space, a complex installation involving a restorer working in the gallery on a number of paintings chosen by the artist for their subject matter, which relate to other themes in her art. The restorer works on a grey backdrop, more commonly found in a photographers’ studio, making her appear staged and the setting somewhat filmic, and she is directed in her restoration each day by Hugonnier. The work will end with the restored paintings exhibited within the space, alongside statements written pre- and post-installation. After it closes, the artist will turn her attention to a film she is shooting in Niger around the work of French anthropologist Jean Rouch, as well as five museum exhibitions, including S.M.A.K. in Ghent and the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland.

Finding my final artist involves traveling back across the river, to the Delfina studios near London Bridge, where Mark Titchner will work until September, when the space sadly closes. “This is the only place in London that offers something like this,” he says in his frustration at the closure. “It’s amazing to be around the international artists who have come in. We’ll have lunch together and whether you’re talking about art or crap, it’s good to have that dialogue.” The timing is perhaps right for Titchner though, who with two assistants working alongside him, has almost outgrown the space, and will be looking for something bigger in Hackney. The move does unfortunately also coincide with Titchner’s preparations for his contribution to the Turner Prize exhibition, which he was shortlisted for on the basis of his show at the Arnolfini gallery in Bristol earlier this year. His works for the exhibition are still in development and remain strictly under wraps, although a sneak preview does suggest that they will live up to his desire to create a “visual overload, to batter it into your head.” While nervous about the notoriously savage response that the British tabloid press gives the show, Titchner is excited about the recognition it represents. It all seems a long way since the early days at Vilma Gold, when, he explains, “we used to wait around for Charles Saatchi to turn up; he was literally the only collector,” a comment that suggests just how far he, and London’s art scene, have evolved.