Since the late 1960s, British artist Anne Bean has been singularly dedicated to performance and relational art that exists in its own moment — so much so that she has consistently resisted efforts to analyze her five decades of work and its influence. The past year has seen both an appropriately prospective retrospective monograph of her career, Self, Etc. (Intellect, 2018) and an exhibition at London’s England & Co. gallery. The latter, titled “How Things Used to Be Now,”captures her desire for all art — not just her own work — to be considered in a deeply personal and constantly shifting “continuum” that includes “all the life in-between.”1

For Bean, this has often meant incorporating sounds and references from popular music, ranging from her all-woman glam-rock band Moody and the Menstruators, to punk nightclub performances with the Kipper Kids, to her more recent evocative work with the Bow Gamelan Ensemble.

Fortieth-anniversary celebrations of punk in exhibitions like the British Library’s “Punk 1976–1978” and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Punk: Chaos to Couture” have revived interest in artists like Bean, whose performative practices often introduced the art world to musicians from this burgeoning scene. In these excerpts from an interview with art historian Maria Elena Buszek, Bean addresses some ways in which her work has engaged popular music and feminism.

MARIA ELENA BUSZEK: What first drew you to begin using popular music in your work?

ANNE BEAN: My dad was both a classical and a jazz musician. He had come from London, invited with his band to do a residency in a hotel in South Africa and afterwards in Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia.) He ended up in Zambia, where I grew up.

He had a varied record collection. I remember mostly putting on women singers and being intrigued, absorbed, and often thrilled by the audaciousness and brazenness of both the lyrics and the delivery. Eartha Kitt singing “I Want to be Evil” and visceral lines like “I want to spit tacks,” in which I imagined the saliva and the sharp metallic tacks being spat from her mouth.2 I found Sophie Tucker amazingly suggestive and risqué and often hugely prescient of what became central feminist issues; Peggy Lee’s “Fever” was immediately catchy — the fever heat was there but also an absurd vision, as I imagined feverish spots breaking out on the singer’s face. This “otherness” felt liberating and subversive, as though songs, more boldly than literature that I had come across, were permissive, giving space to girls/women in which to explore fantasies and dissonance.

In the Zambian town, Livingstone, that I grew up in, my friend Jeanette Iljon’s parents owned a record shop, so we often browsed. I remember listening to Odetta together, especially “Water Boy,” in which Odetta’s body seems to push out the sound from deep down whilst slapping the guitar so hard that it seemed to bellow with her. It thrilled me to hear that fusion of instrument and voice, the connectivity and physicality.3

The record shop was also where I first heard South African singer Miriam Makeba sing “Qongqothwane (The Click Song),” a traditional song of the Xhosa about a beetle believed to bring good luck and rain. I loved the resonant clicks that seemed to dance and pop, as if the mouth chamber and tongue had stiffened and morphed into the beetle’s body.4

MEB: You’ve mentioned Yoko Ono as an influence in your work.

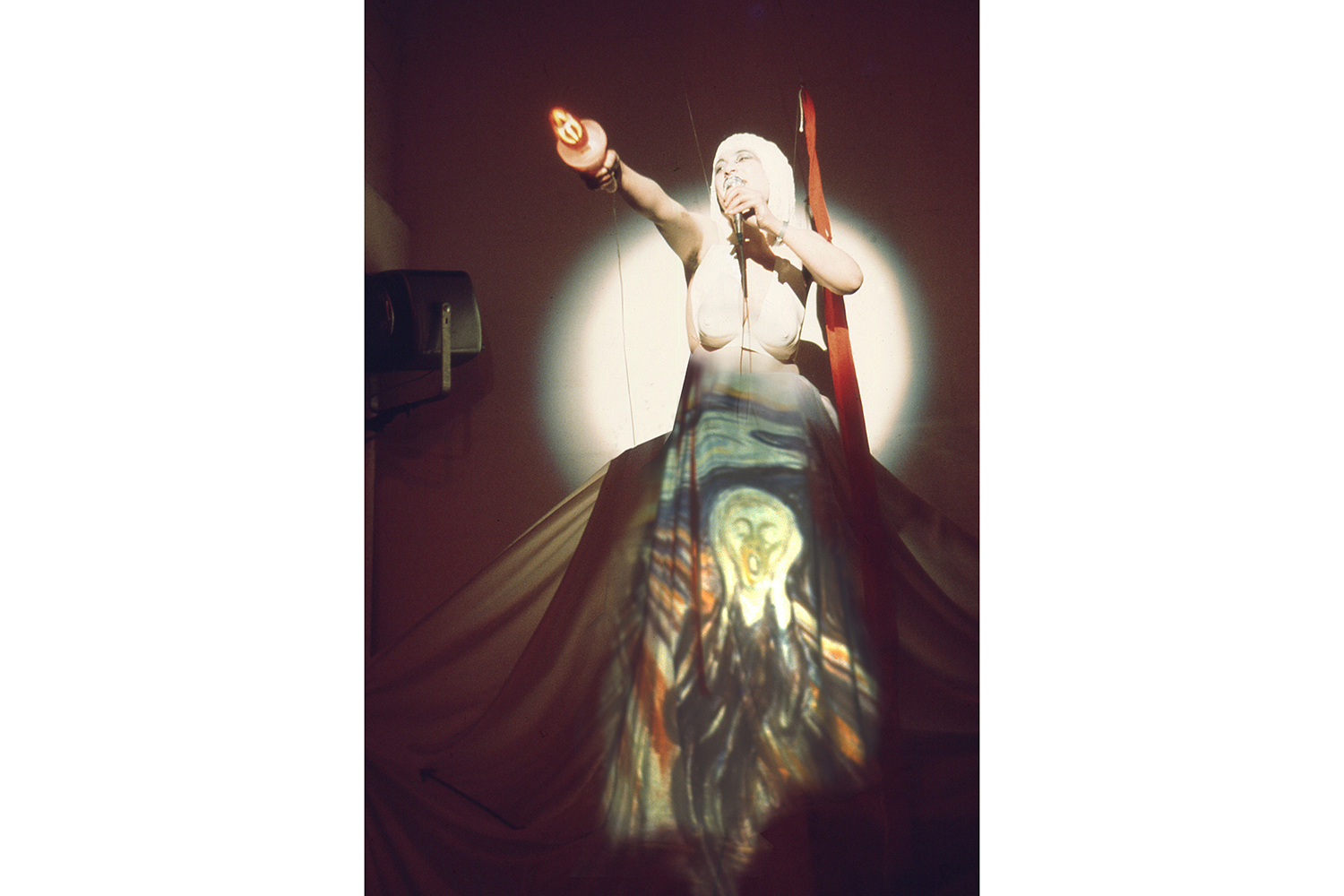

AB: When I first heard “Midsummer New York,” her sweaty, frenetic, frenzied hymn to New York in that leaden July heat, it totally grabbed me, especially knowing the conceptual poetic works of hers. The song is primal and corporeal, feral and strung out. I sang a version of it dressed as the Statue of Liberty with Munch’s Scream projected on the drapes and a throbbing flame light pulsing shadows through the room.5

MEB: Were there other musicians that influenced you?

AB: I was drawn to Janis Joplin. It was through Joplin that I listened to Big Mama Thornton, especially her album Stronger than Dirt, and finally saw her perform in Los Angeles as a fragile Mama Thornton, but still rousing and chiding the spirits with her own “Ball and Chain.” At that time I was captivated by Vera Hall, especially singing “Wild Ox Moan”; the rich depth of this haunting song and her effortless, mellow voice made it appear to be drifting over the prairies.

Coming to Reading University to do fine art in 1969, I met Christine Jeffries, a painter and singer, now a Buddhist nun. It was originally through her I was exposed to free improvisation. Recognizing that the same approach could be brought to sound as to visual art (actually to life itself) was deeply affecting. John Cage succinctly expressed these modalities in so many concise and liberating ways.6

Cornelius Cardew, the composer, who became disaffected with the academic role of music and decided on an inclusive audience and participatory approach, co-founding the Scratch Orchestra, led a workshop at Reading University in 1971. He spoke of his antagonism to “the slavish practice of doing what you are told” and spoke about dissolving the distinction between a musical work and social action. This nonhierarchical structure, emphasizing mutual responsibility and rejecting rigid authoritarianism, similar to Joseph Beuys’s concepts of social sculpture, had a huge, freeing effect on me.

At around this time I went to Belgium with the Kipper Kids, Robin Klassnik, and Cosey Fanni Tutti and Genesis P-Orridge (who had recently formed COUM Transmissions). COUM/Throbbing Gristle had a studio at SPACE studios, Martello Street, where loads of artists congregated and events often happened — as well as Gen and Cosey, I knew Robin and Bruce Lacey and would hang out there from time to time. This later led to them performing in my studio at Butlers Wharf with Chris Carter and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson. The sublime frenzy of sound was riveting.

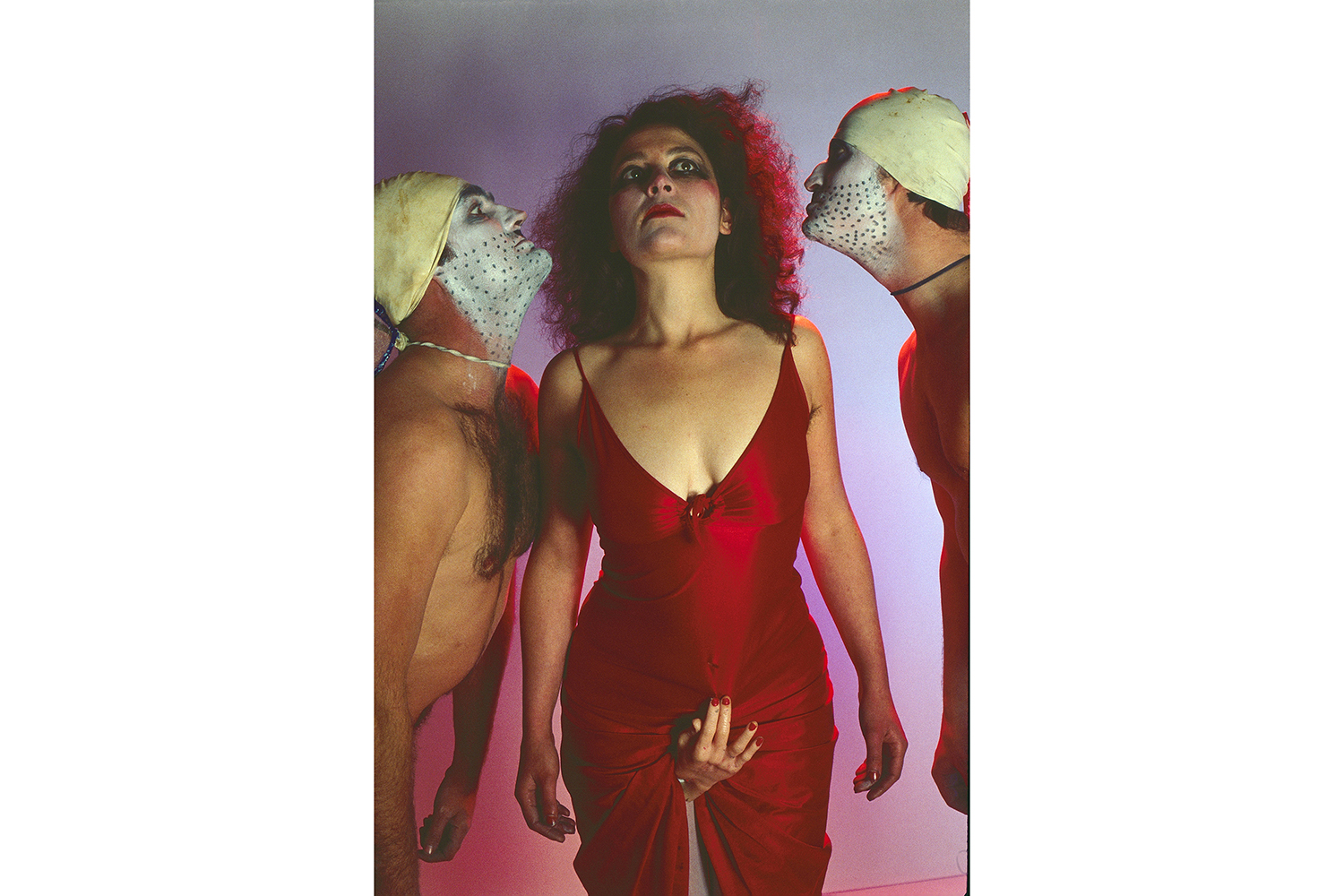

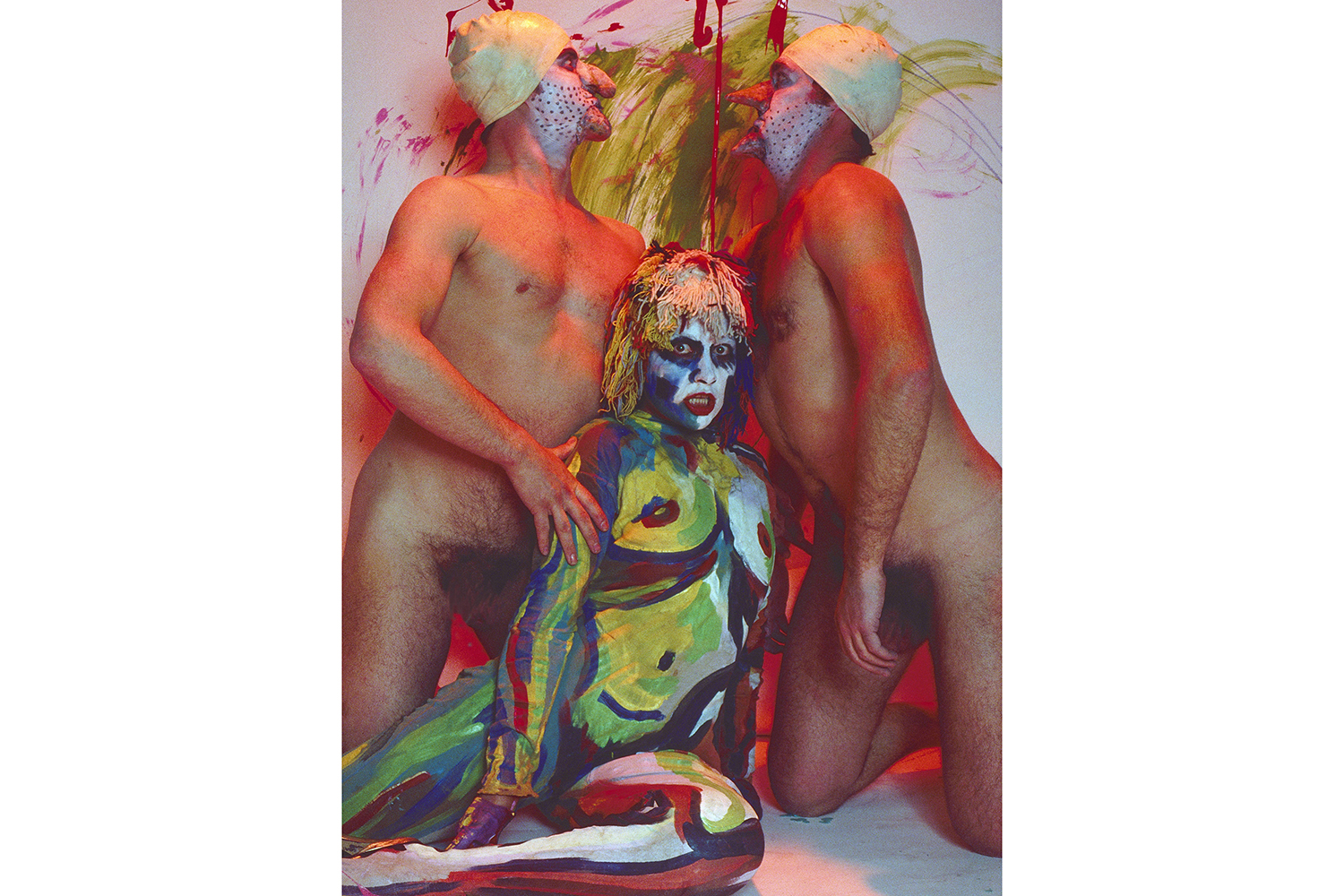

MEB: Simultaneously, you were performing punk-rock personae that arguably preceded punk, as Anne Archy with Moody and the Menstruators (active 1971–74).

AB: Moody and the Menstruators was meant to be a one-off event of absurd, in-your-face high-energy jocularity, confrontational and erotic, whilst simultaneously sending both those stances up. It seemed to immediately gather a cult following, and we were invited to other gigs. Brian Eno was involved in Portsmouth Sinfonia, and through this and various other channels, Moody and the Menstruators invited and supported Roxy Music for their first gigs, held at the art department at Reading University.

The dilemma was how to keep the verve and spontaneity and craziness. Our first gig in London, organized by Robin Klassnik in 1972, was at a flashy nightclub, the All Nations, where I asked the two strapping security guys to carry us on stage, one at a time, covered in gift wrap and bows, like giant presents, and put us each on a plinth. We then burst out of the wrapping with the song “Sh-Boom,” everyone doing the harmonies but me singing the words “Life could be a dream…” in a number of styles. I was wearing a bra over my sequined dress with thigh-high rubber boots used for cleaning drains. The others had similar mismatched ensembles.

Half the audience, mostly the usual clientele of the club, was absolutely baffled, whilst the ones we had invited hollered enthusiastically. Audience reactions remained divisive, not improved by me singing the song “Mona Lisa” with a gold frame around my head whilst trying to keep a mysterious smile on my face or by singing “Wild Thing” with a wet suit and extremely bad bass playing whilst Rod, in a tutu with a blonde wig, leaped over a cloth rainbow, purposefully getting more and more breathless whilst singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” As some booing erupted, we sang the Drifters’ “You’re Adorable” very sweetly and enticingly to them all. There was a similar dichotomy of reaction at Dingwall’s, whereas at the Spare Rib benefit we were unanimously and loudly fêted, from Eartha Kitt’s “Evil” to Captain Beefheart’s “Electricity.”

MEB: Was Spare Rib important to you as a feminist? Did you disagree with some of the journal’s politics or choices?

AB: I was often asked if we were a feminist band. It was a quandary for me. I discussed this with the feminist artist Alexis Hunter, who had attended many of our gigs, including All Nations and Spare Rib.

We spoke about boundaries between expressions of sexual warfare on the one hand, and erotic desire on the other, both

of us touching that fulcrum of subverting and animating the male gaze by triggering layered, confusing signals.

Alexis wanted me to declare myself and the group as feminist. I wanted to be confrontational and subversive outside of labels, without proselytizing. I liked the unsettled, the uncatchable, and the mysterious Anne Archy of Moody and the Menstruators, perplexing and baffling, squeezing mustard onto my meat dress as fleshy rubber hands crept intimately around my body or clasped my stockings, in lieu of suspenders. Whilst Alexis inked over a male erection, burnt silver stilettos, and axed down walls.

Our dialogues overlapped Germaine Greer’s positioning [at that time], with which I felt empathetic. I thought Germaine had been much more challenging than any performance work I had seen referencing the naked female body when Suck, in 1972, published a naked photograph of her lying down with her legs over her shoulders and her face peering between her thighs and her anus taking center stage.

In an interview with art historian and curator Elizabeth Eastmond, Alexis summarized the Moodies’ place in this moment:

The punk movement and artists came together in the studios at Shad Thames in the London dockyards. Anne Bean’s 1973 performance-band the Moodies had a cult following with artists, especially feminists. She would sing in a black rubber diving suit, the other women in the band in pink silk French knickers and vests. The lyrics of punk songs then were very political. By 1976, Anne was holding warehouse parties at Shad Thames, where I heard Siouxsie and the Banshees.7

MEB: You also performed at the legendary Los Angeles punk club the Masque!

AB: The writer/photographer Elisa Leonelli described our performance there in 1979: The punk audience responded to their aggressive performance by throwing cans of beer and food at them. Surprisingly the Kippers didn’t strike back, as they had done against a couple of counter-performers at their first LAICA show. They just shortened their act and got out.8

We were told to get out by the management, who had previously been totally gung-ho about encouraging wildness.

MEB: Yes, well … getting kicked out of the Masque for being too punk is pretty fucking punk.