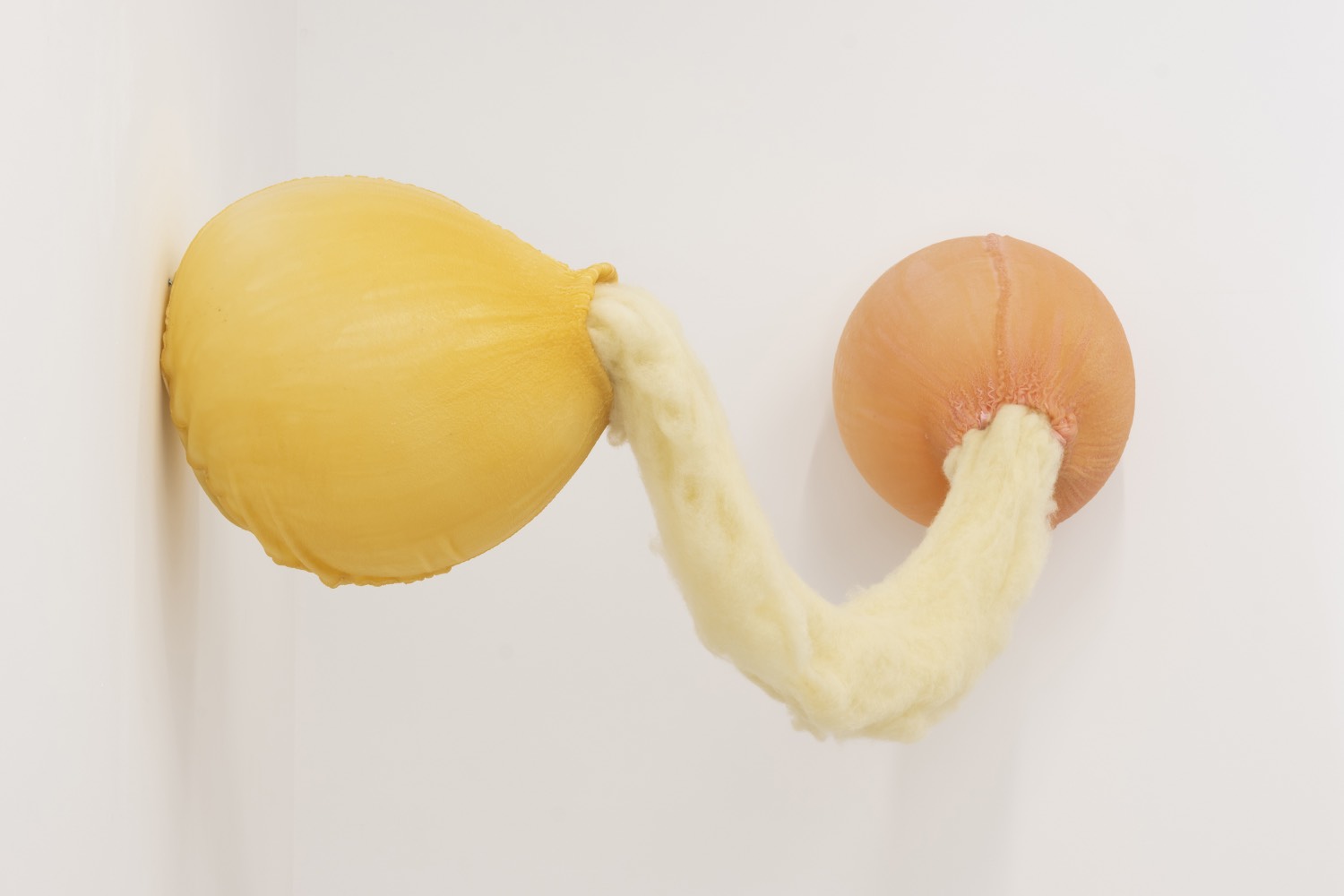

A colony of massive, spherical forms infiltrates the panopticon architecture of M|A|C Mataró, a former prison turned art museum near Barcelona. These parasitic sculptures, in tones of copper, yolky yellows, off-whites, dark purples, and rusty browns, belong to a new series by Barcelona-based artist Eva Fàbregas, presented on the occasion of Manifesta 15. Titled Exudates (2024), their long ovoid chains capture how organs or flesh respond to tension and release. Shriveled where the tautness of their ballooned understructure has slacked, they resemble something in between Jurassic cocoons and dry-aged anal beads. These large-scale sculptures are made by testing the plasticity of synthetic fabrics and latex. In the studio, Fàbregas skips the rules: she layers the latex without a mold, piles it up more than ten times, reinvents recipes, and bends instructions. Never fully allowing the material to settle, she then experiments with inflation and deflation. This method makes distinctive surfaces akin to skin marked by time and lived experience. Part of a series originally developed for Vienna’s Klima Biennale 2024, these works expand Fàbregas’s haptic desires into new, moodier, and wrinklier forms. Named after the substance that oozes from living organisms in response to injury or inflammation, they’re perhaps a metaphor for the deeper ways Fàbregas projects her feelings onto the works.

Sometimes her sculptures are sensuously bulbous, like yielding vessels: wombs or wounds in bright reds and pinks. “Sheddings” (2021–22) are phallic, breast-like, nipples with gloopy condoms in pastel hues. Other times, these objects climb up the wall like caterpillars, all-devouring, or hang from the ceiling like large bloated intestines clinging to their surroundings, as seen in Tangles (2017–21) or Growths (2022). Like the 1980s children’s TV show Once Upon a Time… Life, these works shrink us to a microscopic level for a tour of the human body and its weird and wonderful cellular life. Fàbregas dreams of sculptures that have a sense of self: she imagines them dancing in nightclubs, diving into oceans, or floating in space — capable of reproducing and mobilizing. She takes them out for walks, not as a performance but as “something nice to do before long periods in storage,” as documented in the installation of “Enredos” at Centro Botín, Santander, in 2023. Like Frankenstein, Fàbregas calls them her creatures; they are the result of experiments and misbehavior in the lab. Undoubtedly alive, they seem to be in constant flux, in the process of becoming human while inviting us to be more like them. Her creations call for tactile engagement, physical intimacy, sensorial relations, and somatic experimentation. Occasionally, the sculptures vibrate with sound and suck through breast pumps, as in Pumping (2019), and are large enough to rest upon. In Picture yourself as a block of melting butter (2017) visitors put on a suit made of the same stretchy fabric as the sculpture and, while lying on it, listen to a guided meditation on how to metamorphose into the work. This aligns Fàbregas’s practice with artists like Lygia Clark, in particular her relational objects, and Eva Hesse’s interactive sculptures, through what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick called “the performative affect” — the idea that objects, like sculptures, can embody and convey emotions and that human interaction with these objects can evoke powerful affective responses, revealing a dynamic relationship between affect, materiality, and human perception1. For the artist, touch is a primary source of knowledge, conjuring a prelinguistic stage to relate to other bodies (human or otherwise) in renewed ways.

Sculpture, for Fàbregas, is a relational practice, a tactile conversation between her body and nonhuman matter. Her works emerge in relationship to the places they inhabit, challenging the traditional view of sculpture as merely shaping matter. Instead, she listens to the materials, allowing them to shape her process as much as she shapes them. In the 2022 book Parallel Minds: Discovering the Intelligence of Materials, theorist Laura Tripaldi explores the idea that materials around us are not just passive objects but can be seen as intelligences with the ability to respond and adapt to environmental stimuli, thus participating actively in the construction of our world. She argues for a broader understanding of intelligence that extends beyond human-centric definitions, like the slime mold, a unicellular organism that demonstrates remarkable problem-solving abilities and can navigate complex environments efficiently. This organism’s behavior shows that even simple biological systems can exhibit sophisticated, adaptive behaviors2. Fàbregas’s practice follows this principle and proposes new ways of sensing and relating to the world.

Like sap bleeding from a tree after a cut, Fàbregas’s Exudates desire to burst and pour into the building’s cracks, healing and regenerating the defunct prison, breathing life into it. Air is Fàbregas’s primary material, one that has fascinated her since childhood, when she trained as a soprano singer. Like touching, singing provides an embodied form of communication and is a source of knowledge. Consciously inhaling and exhaling requires practice and has healing effects; a deep breath can reset the nervous system or relieve pain. In the essay “The Ambivalence of Air” (2023), writer Daisy Lafarge discusses air as a cure and an agent of death, a carrier of contradictions, pointing out its essential yet potentially dangerous qualities that we have become so familiar with since COVID-193. For years Fàbregas lived and worked among her sculptures in a small place in London, where she moved to study for an MA in Fine Arts at Chelsea College of Art, in 2013. The lack of space turned the relationship with her work “toxic”: unhealthy due to her proximity to harmful chemicals and the cross-contamination between life and work. Inflatables became a practical solution to her problem — easy to pack away. Thus, replenished with air, Fàbregas’s beings are resurrected into blowing entities that occupy space intimately and expansively. In Exudates, Fàbregas furthers her interest in the volatility of air as a material, exploring its weathered parts beyond the surface. As Lafarge ponders in a different text, “foggy or transparent, air portends a state of doubt, where nothing is what it seems.”4

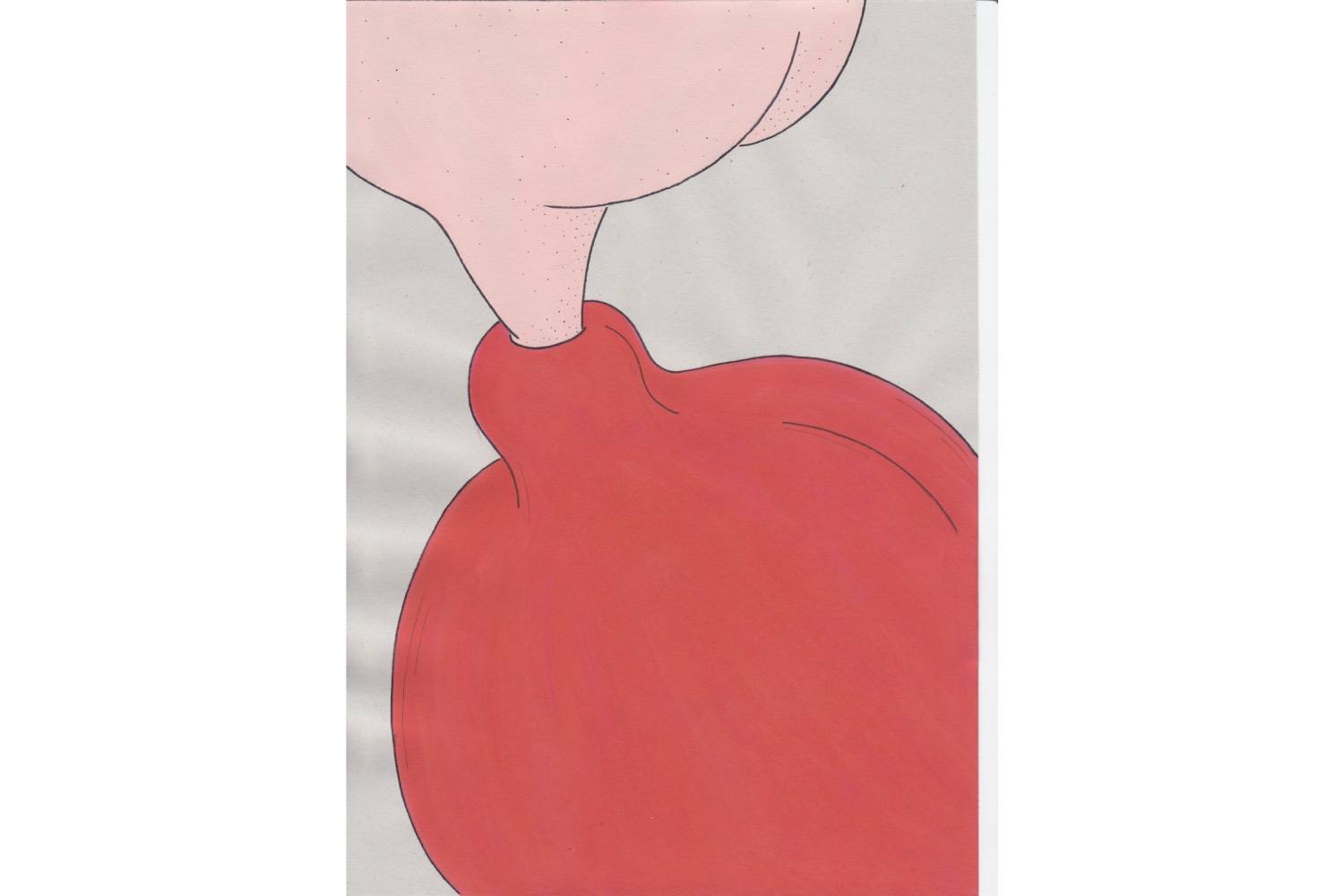

In her exhibition “Devouring Lovers” (2023–24) at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Fàbregas saw the hall’s steel skeleton as a support and a constraint, similar to a prosthetic device. In an interview with the curator Anna-Catharina Gebbers, Fàbregas says it reminded her of having dental braces, a “messy love affair” between her gums and stainless steel. After taking her braces off, the artist still felt the phantom touch of the cold metal and missed it5. Fàbregas envisions a future where sensorial experience and symbiotic relationships redefine our interactions with technology and other life forms. Influenced by Octavia E. Butler’s speculative fiction, Fàbregas uses sci-fi visual languages, like those of Rick and Morty, to sexualize the organic and queer preconceptions of bodies, fluids, and all things slimy. For example, her acrylic series “Polifilia” (2020–ongoing) shows otherworldly creatures that could be from the ocean floor or the intestinal tract, some hairy, some flat, interacting sexually with one another and foreign objects. As if enacting their etymological meaning: polyamorous, the love of several or many. She sees her sculptures as extensions of the human body and the surrounding architecture, and is compelled by these intimate, sometimes painful aspects of relations, material or otherwise. Prosthetics are clear representations of how our bodies interact and are supported, enhanced, or taken advantage of by external objects.

Fàbregas has made several works that relate to this two-faced symbiosis. Bite Plate (2019) is a basin, based on orthodontics correctors and retainers that prevent teeth grinding and jaw tension, filled with pink slime spilling over and contaminating its environment. The slime recipe was taken from YouTube videos, where kids mix household materials to create a substance they ply, poke, and squeeze as a calming therapy linked to ASMR — which uses tactile, auditory, and visual triggers to induce euphoric sensations, mimicking bodily, taboo, and formless experiences through an unnatural mediator. Shaper (2019) copies those devices designed for swimmers to hold their nostrils closed and prevent water from entering or air from escaping, absurdly amplified at a 1000:1 scale. Fàbregas reversed the calibration system used in architectural modelling to repurpose this gadget as an element that corrects, shapes, or retains the wall it holds. Kimberley and Chloe and Nancey (both 2019) are enlarged ear molds formed through a flocking technique, creating a soft, textured surface that evokes a child-like comfort and desire. Made giant and displaced from the canals that define them, these shapes resemble vibrators and interact erotically with the room. In the interview mentioned above, Fàbregas discloses, “I think that my sculptures are not so far from prosthetics. They become an extension of our bodies and the architecture surrounding them. Or maybe it is us who become an extension of them.”

Fàbregas’s sculptures embody an amorphous presence that disrupts and redefines the architectural spaces they occupy. They are exudates, intuitive expressions of a messy, visceral love affair with matter, pushing toward a restorative engagement with the tactile and sensory dimensions of our existence. Fàbregas’s strange materiality may be so in order to reflect the unknown and the unmanageable aspects of life, to resist the urge to continue a language that separates humanity from nature. That keeps things too clean.