Hi, my name is Pierre Bal-Blanc. I was born in the small working-class town of Ugine, in France. I live in Athens and Paris. I am a freelance curator and essayist, with a current income that is roughly the minimum wage.

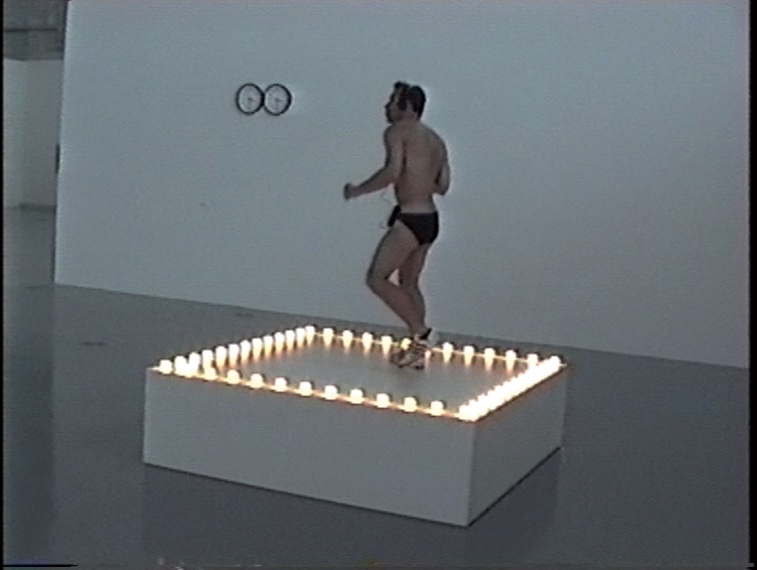

In 1988, when I was still at the Lyon art school, I undertook a groundbreaking project titled and signed Jeff Wall. Some friends and I put on a group show in an apartment in the city, which had the title “5 human beings exhibiting.” For the five posters that made up the communication we created stylized logos based on our respective visual works. My contribution was an essay about the Jeff Wall exhibition 1 that was on at the same time in the Nouveau Musée in Villeurbanne (now known as the IAC). My text, focusing on the artist’s color transparencies, 2 repeated the Jeff Wall patronymic throughout its critical analysis; it was presented on a wall and available as a photocopy on a table in the show, as well as by mail. My subject was Jeff Wall and I was Jeff Wall. A few years later, I was working putting up exhibitions at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg. The Kunstverein was looking for a volunteer to carry out a paid daily task that took a minimum of five minutes, for two months, as part of the exhibition “Gegendarstellung: Ethik und Ästhetik im Zeitalter von AIDS,”3 which enabled you to decide when you would honor your contract within the institution’s opening hours. That is how, for that period of time, I became the art object (or in any event a part of it), conceived by Félix González-Torres, “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform) from 1991.4 This is what makes it possible for me, today, to testify as to the object of that experiment. In this respect, it is one of the rare “object gazes” to have been formulated. Marcel Broodthaers, who signed an “authentic and real artwork” by Piero Manzoni,5 conjured up in his day his viewpoint as an art object. In 1969, with her Petite Femme Television, Nicola L declared: “I am the last woman object.” From then on, her sculptures would break up the traditional visual syntax and use the concept of epidermis, which has the virtue of unifying all skins. With the exhibition “January 15 – February 10, 1977. Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art,” Michael Asher scaled down his intervention to employing people to remain in an empty space, then publishing the written reports submitted by the participants.6 More recently, Tino Sehgal with This objective of that object (2004) investigated a similar configuration.

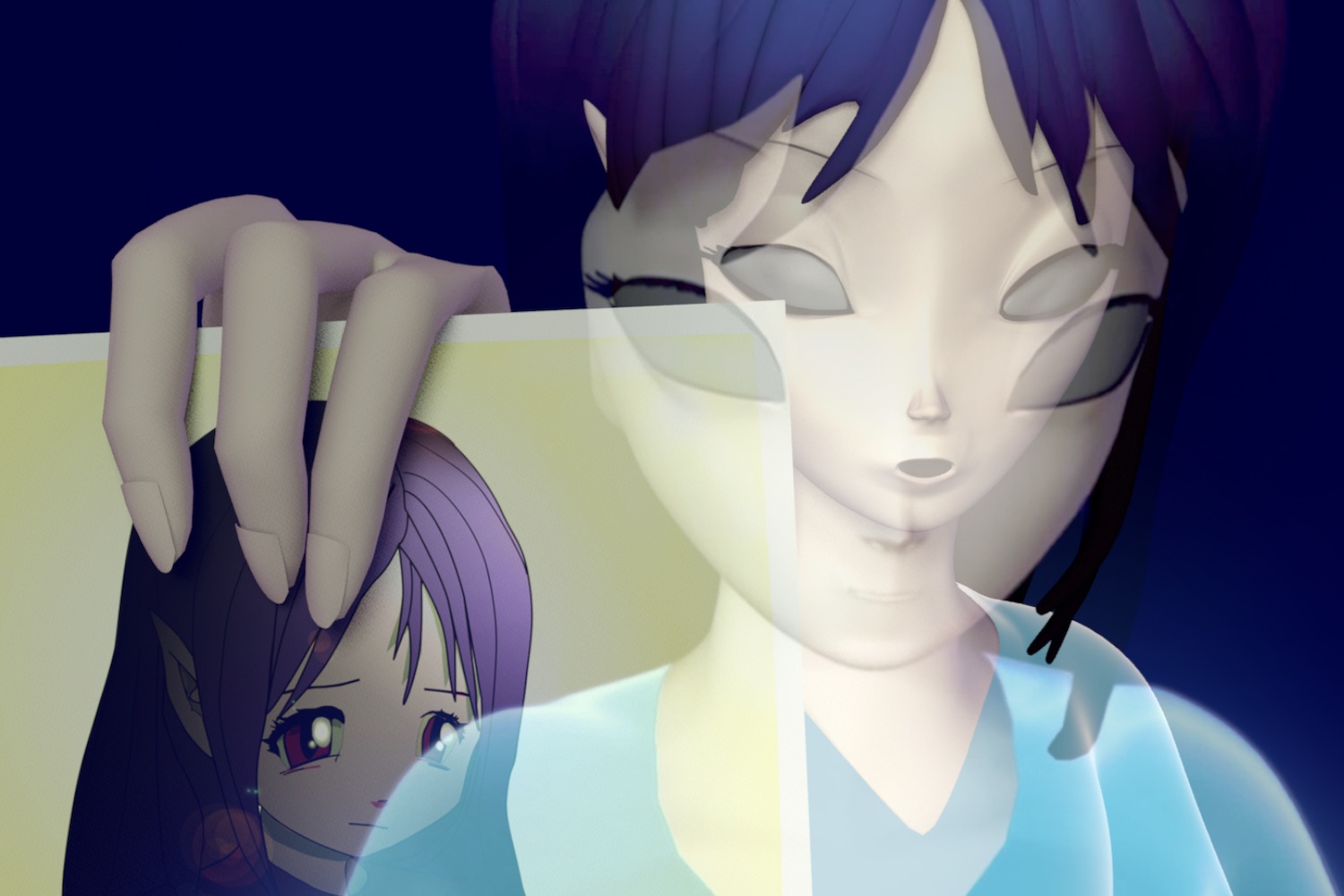

It was in answer to the recent invitation from Manuel Segade to the CA2M at Móstoles, 7 in the suburbs of Madrid, to take part in the tribute being paid to Félix González Torres by the ARCO fair, that I transcribed that objective viewpoint both literally and figuratively. But I had already objectivized that gaze at the time, in 1992, by recording my daily task in a video that I called Contrat de travail [Work Contract] (After Félix González-Torres), 8 to render the inner structure of the Cuban artist’s work visible and lend substance to the viewpoint of the performer executing that work. The reversal of the gaze that I carried out on that work, which itself proceeded from a reversal of perspective, in which the visitor to the exhibition perceived just a pedestal waiting to receive a body, or the spectacle of a dance turned toward itself, tallied with a new aesthetic of reception that would develop between the 1990s and today — for example, with the recent use of González-Torres’s work by Mahmoud Khaled in Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform) Speaks, 2016. 9 In the month following my service rendered to González-Torres, I was working at the Deichtorhallen with Elaine Sturtevant, who was showing, in her exhibition, one of the first expressions of that aesthetic, no longer rooted in production but veering toward its reversal in the direction of reception, with her incarnation of Duchamp Nu descendant un escalier from 1968. 10 Shortly thereafter, that led me to become involved in Pierre Huyghe’s research, working as his assistant in the gallery where I was working in Marseille, 11 which gave rise to the work Blanche-Neige Lucie in 1997 — to that type of reversal in which he reinstated the subjectivity of the French female dubber of the Disney Studios Snow White (1937) film sound track, fighting to regain the rights to her voice. In Mexico, in 2002, I subsequently met the artists Santiago Sierra and Teresa Margolles, who, from 1998 onward in Mexico City, had started work on a series of pieces about the commodification of the most destitute member of the work force. For the Spanish artist, in exile in Mexico, the works laid bare the rate of pay in effect in the labor market. Line of 30 cm Tattooed on a Remunerated Person (1998) thus objectifies the people involved by reversing the principle of contractual confidentiality, incorporating in the work’s title the information about their wages and their work conditions. Teresa Margolles, for her part, after her involvement with the SEMEFO collective,12 started to give shape to her semiotic matter. For example, in the permanent work on view at the CAC Brétigny, Fosse commune–Fosa comùn (2005), the organic clues concerning the populations decimated by violence in Mexico are used by the Mexican artist like a sort of resin — an approach that still characterizes her work today.

The introduction to this text borrows the biographical form used by Jérôme Bel in one of the most emblematic spectacles produced by the choreographer, Véronique Doisneau (2004), which can be regarded as another example of the reversal of perspective offered by a work stemming from an aesthetic of reception.

Bel invites the spectator to take a discursive route that does not go from the author to his object, incarnated by a subject (also meant in the sense of “subject” as given by the profession to the dancer to distinguish him/her from the corps de ballet and the soloist).

He proposes an object, the practice of dance, formulated by a subject, the female dancer at the service of dance works, heading toward her own subjectivization. The power play is rendered visible by an indirect arrangement with which the spectator identifies more directly. The choreography is not imposed; on the contrary, it fashions the narrative from the real life of the performer, incarnating compound roles including the spectator who confronts what is unsaid and the institution that accommodates this praxis.

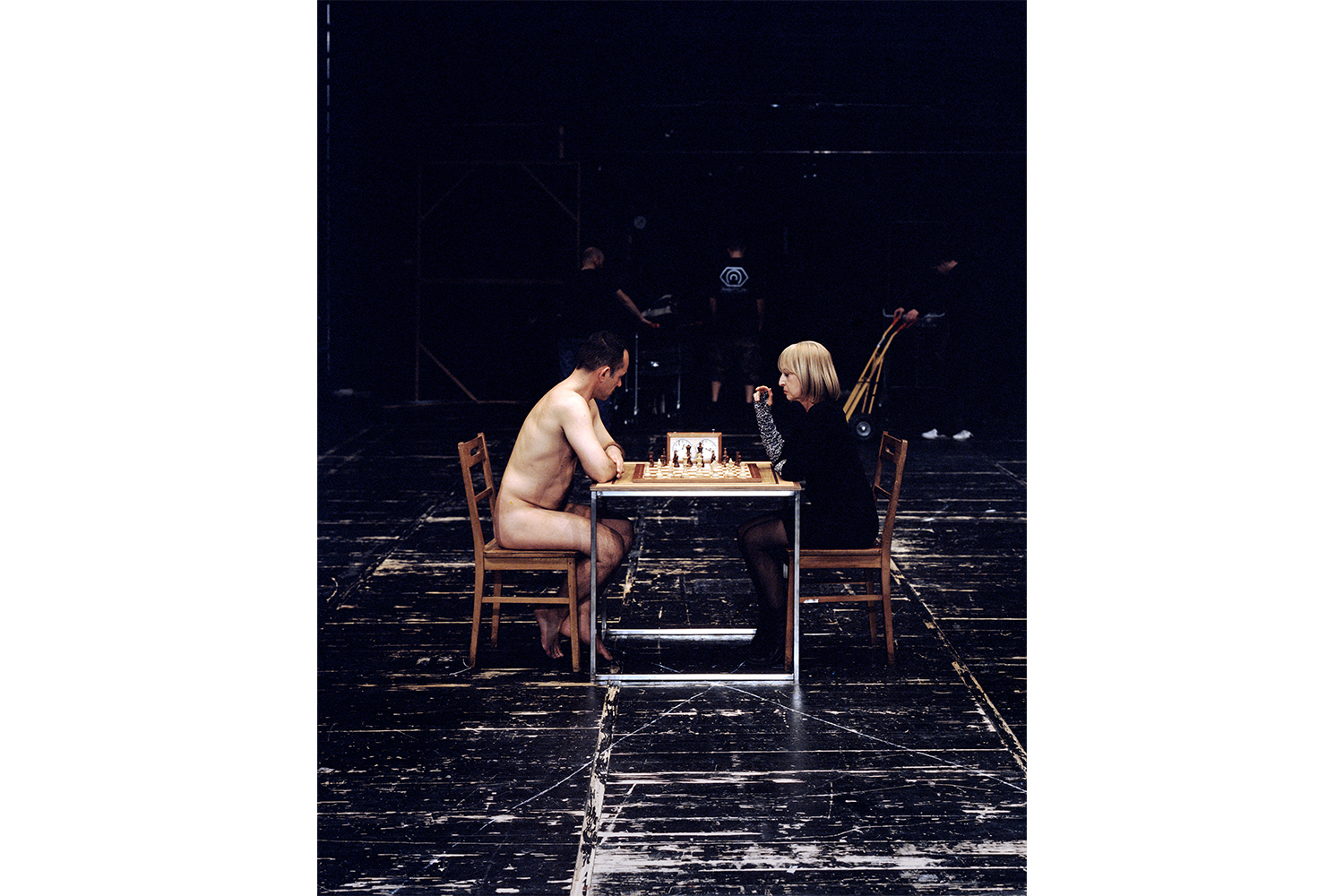

The objectivization of the power play between the author and his model, favoring an emancipation of the spectator, carried out by way of an inversion, is also to be found in the work Eve’s Game (2009) by Sanja Iveković.13 The Croatian artist’s performance is based on a historical document: the photograph taken by Julian Wasser during the Marcel Duchamp retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum, in 1963. In that picture, rekindled in the form of a performance, the artist physically takes the place of Marcel Duchamp and positions the curator, who was responsible for inviting her to produce the project, naked in front of her. Eve Babitz, who posed for the original photo, has contributed to several magazines (Ms. Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar) and published several books, including Eve’s Hollywood (1974) and L.A. Woman (1978).14 She agreed to be interviewed by the art critic and historian Paul Karlstrom for the oral history archives of the Smithsonian Institute of American Art in June 2000. Sanja Iveković replaced the game of chess with a dialogue taken from the conversation between Eve Babitz and Paul Karlstrom, paced by the stopwatch used for chess matches. If the artist took Duchamp’s place as a figure, she conversely incarnated Eve’s answers in front of the naked curator conducting the interview. In this game of switching roles, Iveković proposed a live archaeology of all the image’s hidden levels.

The reading of Iveković’s work frees up the view over numerous facts of the arrangement, for example the one that Vanessa Desclaux expresses thus: “I claim that, by accepting to participate in Iveković’s piece, Bal-Blanc also revealed the ambivalence of his curatorial position, trading a habitual form of distance and detachment with the desire to reclaim another kind of experience; a perverted use of his curatorial function. On the one hand, this action emphasized the relationship of power that exists between artist and curator; and on the other hand, it revealed the passivity of the curator made visible by Iveković’s use of his body and negation of his full control over the situation he had in fact constructed.”15 The reversal of perspective which shifts us from an aesthetic of production to an aesthetic of reception renders obsolete the previous canonical functions incarnated in roles, or personified in institutions, in order to replace them by new authority figures informed by practices or incorporated in buildings, where it is every bit as important to shed light on these power plays. This effort, as recently advocated by Paul B. Preciado relative to the issue of the nonbinary gender in Je suis un monstre qui vous parle (2020), calls for a “transition into the clinical [which] involves a change of position: the object of study becomes a subject.”16

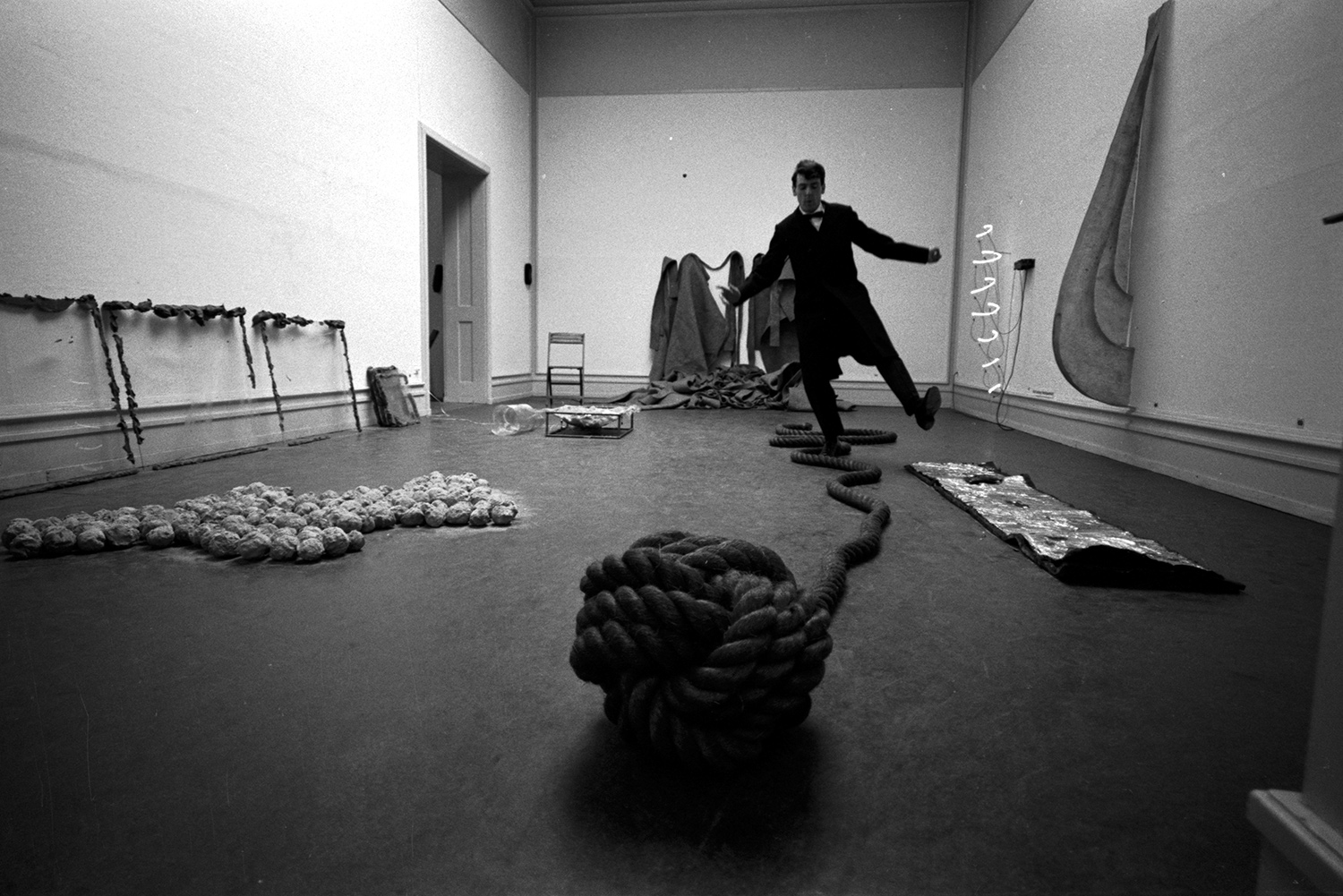

This was the idea behind the group show put on at the Vienna Secession in 2009, “The Death of the Audience.”17 Within the canonical space of the “first white cube in history,” the exhibition sought to prolong the desire for reform of the artists themselves — for example, the definition by John Latham of “the professional outsider.”18 At stake was a wish to abandon the role that art administrators force upon artists by subjecting them to their epistemology and budgetary dependency, and consequently to the system of visibility that institutions grant them. Figures sidelined by the official history of contemporary art, such as, for example, Rasheed Araeen, Bernard Bazile, Odile Duboc, Anna Halprin, Nicola L., David Medalla, Hans Walter Müller, Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, Cornelius Cardew, and André du Colombier, brought together at that time under this title, were not simply clinging to a corporatist revolution; the exhibition imposed on its interlocutors, usually supported in their spectator passion, inverted protocols, making them “actants” or “agents.” In 2010, with Reversibility: A Theater of De-Creation,19 I proposed applying the principle of isonomy (loosely: equality before the law) by incorporating within the constitution — in the sense of social contract — of the group show “dismissal, reversibility, and equality” as compositional principles. Isonomy is a system of governance at the root of the democratic organization of the world in ancient Greece.

This form of discursive production re-casts — based on a principle of equality — the protagonists complying with symmetrical positions around a center. It operates in accordance with a reversibility of roles, with the person adopted in the middle expressing himself in relation to the position of listening incarnated on the outskirts.

The protocol for the first section of the exhibition, which was made up of three parts, consisted in asking the artists to de-create one of their works at the Frieze art fair in London, while remaining free of the means and time that would be taken by this form of mediation running counter to their work. “Soleil Politique”20 at the Museion in 2014 executed, in a tangible way, the museum’s hierarchic reversal. By filling the institution’s ground floor and reception area with works, the curators thus gave the use of the noble exhibition space — surveying the city of Bolzano, situated on the upper floor of the contemporary architecture — back to the population. “Project Phalanstère”21 from 2003 to 2015 at the CAC Brétigny proposed producing works that would participate, over an extended period, in the architectural and functional program of an art center in the suburbs of Paris. This program, inspired by the societal program of Charles Fourier, took the “White Cube” phenomenon the other way (one exhibition after another) by introducing a continuity through asynchronous works lasting beyond the period of the temporary exhibition and becoming transversal in each case. The curatorship of the works stood apart from the cumulative and indexed method of a collection, which is to say not by positioning itself exclusively alongside the production, thus forming a summary, a collection, a family, but by encouraging an aesthetic of reception: the programming creates a composition, an ensemble, a host.

The situated works upset the temporal perspective of the temporary succession by layering timed periods of meaning for the visitor, while at the same gradually articulating, for the benefit of its permanent and occasional users, the place’s inside and outside spaces.

view with les gens d’Uterpan, Teresa Margolles, Nicolas Chardon, Rainer Oldendorf at CAC Brétigny, 2003-2015. Photography and Courtesy Steeve Beckouet.

More recently, “The Canaletto View,”22 co-curated with Kathrin Rhomberg, has made use of the political gaze cast upon the capital of the Habsburg empire, as conveyed in a famous painting held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, commissioned by Maria-Theresa of Austria from the painter Bernardo Bellotto, better known as Canaletto. The urban skyline depicted in this picture has become the UNESCO-certified canon to be respected for the height of new buildings around the Austrian metropolis. The Erste Bank building — located not far from the central balcony of the Belvedere Castle, where the Italian painter set up his easel — has been dimensioned in relation to the pictorial standard. A dozen commissions for works motivated by the curatorial concept, included at different levels of the bank campus, form the reverse image of Canaletto’s ideal Baroque view. These works form a carnal landscape that shows the site’s employees and offer the bank’s customers a chance to embrace a viewpoint that rivals the abstract nature of the monetary movements passing through the building.

This revolution of the gaze is, quite literally, a reversal of perspective of the viewpoint on the art object, and its production, toward the counter field of its reception.

It is rather the “conditions of reception,” be it induced or generated by a work, that inform its aesthetic character, but without doing away with the other aspects of production that are always present. As a result, we leave behind a simple ontology of the object in order to broaden the aesthetic experience to the whole social environment and to all the protagonists in it, artists and performers, curators and technicians, and spectators included. With this system of reception, one does not go about things by replacing a viewpoint — that of the artist to the detriment of that of the curator or spectator — but rather by giving to a whole host of viewpoints the same relevance for building a plural axiology or set of intrinsic values — offsetting an axiological neutrality — upon the situation. In a word, the work gives off not a sovereignty of production encouraging expropriation and exploitation, but a sovereignty of reception that uses appropriation and care.

The exhibition “La monnaie vivante” (Living Currency),23 whose first iteration was presented in 2006 in a dance studio in Paris, takes note of the new economy of bodies and objects involved by the preponderance given to listening to speech, to use terms other than those of production and reception. The social,24 performative,25 or experiential26 turn of the early 2000s, widely commented on in the past few years in its relation to its new time-related format, its link to the living world, and the presence of dance within the museum, has only later — from 2010 on, the date of the last version to date of that adapted exhibition of performances of the work of Pierre Klossowski and Pierre Zucca — been associated with the subject of economy and human resources. In 2006, “Living Currency” immediately established the correlation with neoliberalism and the work force by activating works by Santiago Sierra, Sanja Iveković, Jens Haaning, and Teresa Margolles, introducing these issues into their activities from the 1990s on.

The title of this exhibition is taken from an essay with the same title, which had a limited readership and was published in 1970.27 Through the unnatural association that the authors produce between the two terms forming the title of that literary and visual essay, they reinstate the place of economy by including it actually within the body. This visual treatise then demonstrates that the notions of value and price are present in the production of voluptuous emotion.

Its title alone is the statement of a hypothesis that causes the guarantee of the integrity of the person to wobble on its pedestal, together with the certainty about the neutrality of the object, by avoiding the last resort of a return to a mystical form of animism or to a historically situated theory of genre.

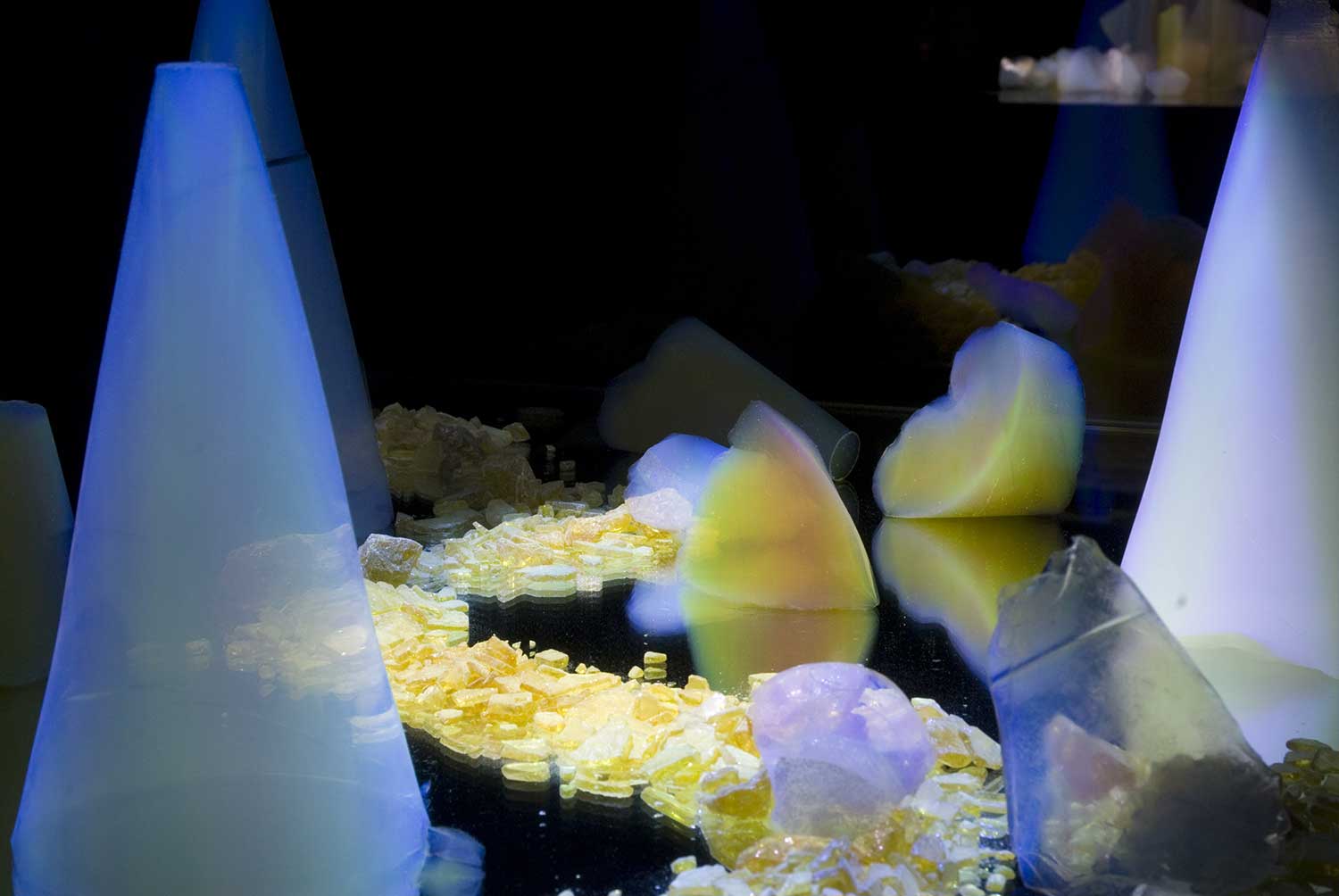

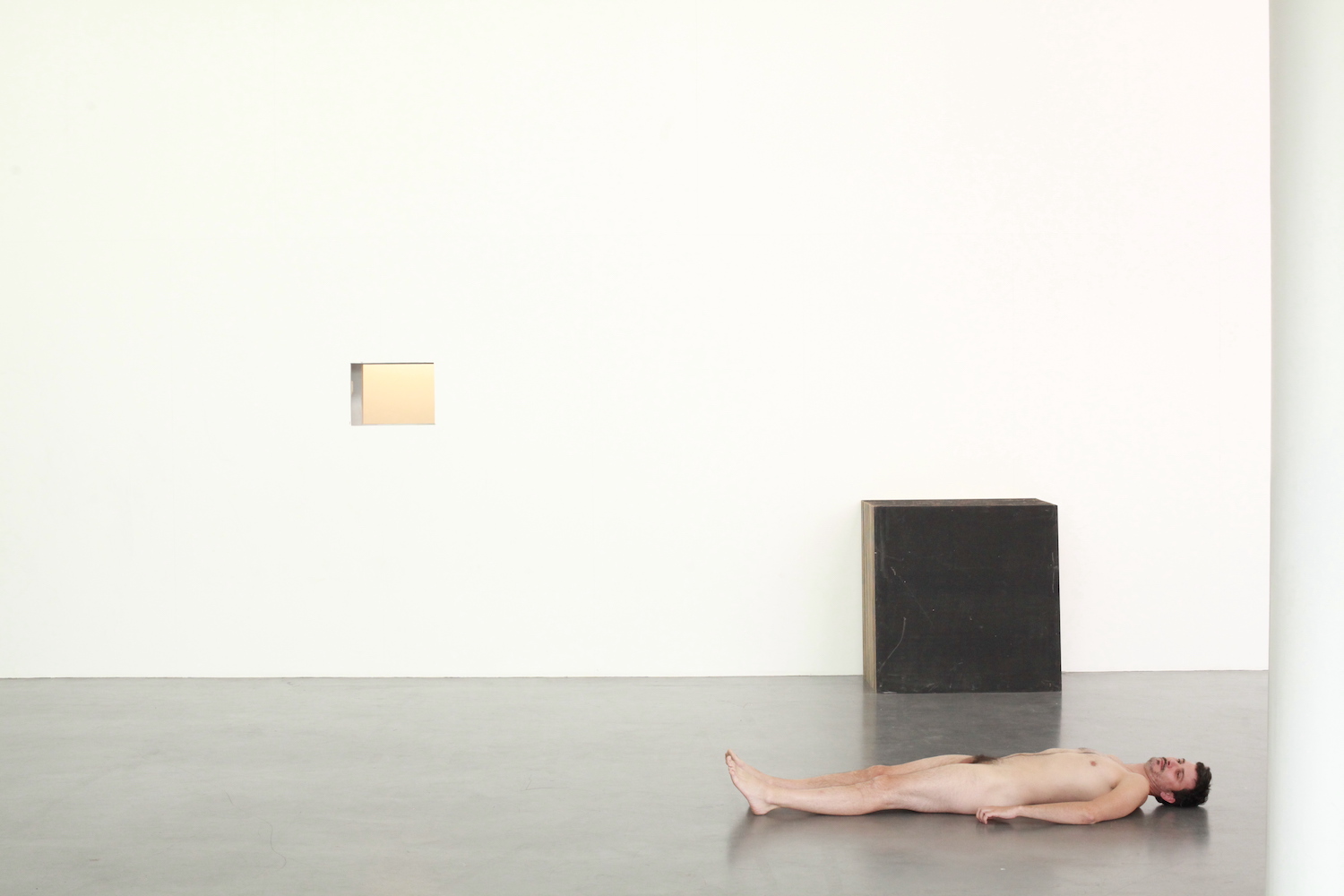

The exhibition, proposed as an actualization (and not an illustration) of the collaborative work of writer and photographer, focuses on defining the spectacular and anti-spectacular means with which authors and artists within visual and performing arts disciplines manage the presence and absence of the body today — the way their “performative objects” contaminate the body of the public and show both the division and the unity of the individual.

The “living/object” and the “inanimate/body” are the two figures, overlaid at the crossroads of the fields of vision, offered by these two professional trajectories. Although the processes involving the perception and presence of the object and the body proposed within the performing arts and among visual artists are evolving in accordance with different criteria and contexts, they are converging on a common territory.

It is from this terrain of practices that I am speaking to you.