Some of us have an unquenchable thirst for fantastic realism, thinking the most sensitive readings of today can be traced from disasters, wars and victories taking place in the breach of time and space created within those narratives. Emre Hüner’s complex, sensitive and dexterous work arrests time’s flow in the form of a speculative narrative of disrupted episodes. Hüner has attracted the attention of many with his two-dimensional, dystopic, post-Virilio visions in Panoptikon (2005).

Hüner works intimately with a keyword-oriented archive of second-hand photos, books, films and various images acquired through the Internet. History, modernism, naturalism, colonialism and technical inventions are some of his keywords. This close relationship becomes clearer with the artist’s book Bent 003 (2007). In these tempera-on-paper drawings of curious objects, parts of nature and architectural components are re-assembled as (un)familiar and ambivalent scenes, reminding the viewer of diverse times, spaces and memories about a colonialist pioneer society through their timeless limbo. Hüner’s Wunderkammer of images and films related to mass-utopian architecture are a recent addition. The artist points to a “dreamworld” built upon the betrayal of a history that shattered “the dreams of modernity — of social utopia, historical progress, and material plenty for all,” in the words of Susan Buck-Morss arguing the fall of mass-utopias in the East and in the West.

The Benjaminian concept of the “dreamworld” refers to a collective mental state inextricably linked to the re-enchantment of the world. Hüner’s overly aestheticized re-assembled universe offers us a mental state that speculates on a re-enchanted afterlife, after the catastrophe caused by post-industrial, postcapitalist betrayal.

Shot after Panoptikon, mostly in and around Istanbul as a personal response to German sociologist Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society, Boumont (2006) presents a catastrophe-struck future, obviously hit by the mass cycles of production and consumption. In his first video, Hüner edits abstracted and detached city views to construct this sci-fi looking wasteland in a place of complete melancholy. The protagonist — like the male prisoner in La Jetée (1962) sent to the past and the future to summon them for the present — arrives from an unknown departure point and traces his past with the help of some old photos.

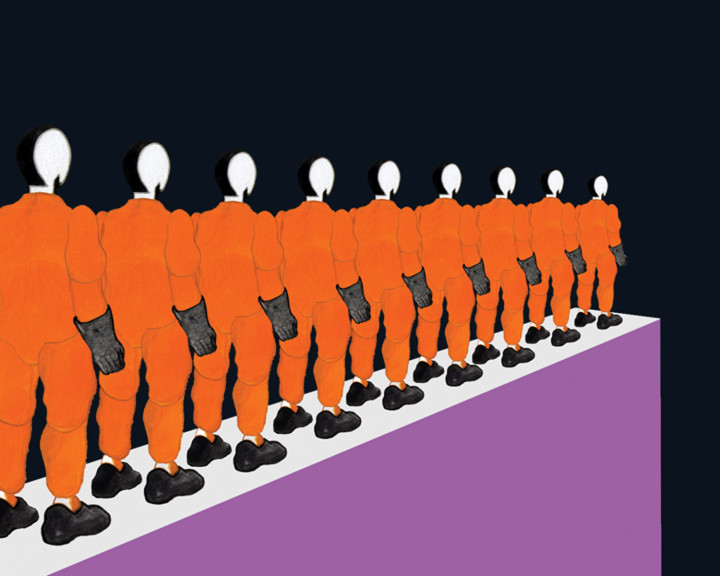

Total Realm (2008), especially produced for city screens, reveals the artists attraction to the structures of fallen mass-utopias, of fascism and socialism, and to images of totalitarianism. With this work, it is more clearly felt that the outcomes of Hüner’s detailed artistic process function as a viewer’s interface to enter his sophisticated and puzzling dreamworld.

The artist once said Istanbul is a city where he feels more like a foreigner. This statement refers to his multi-layered vision of men and modernism through which he is already interpreting the city’s experience on a particular aesthetic level. It seems that his dreamworld, murmuring different episodes, will keep re-enchanting us. However, some parts of his Wunderkammer will remain a mystery.