Fresh, febrile, shot through with humor and glamour, the paintings of Emily Mae Smith are reliquaries of art history and pop culture. Approaching her jewel-like paintings necessitates the activation of a set of iconographical coordinates. If missed, the paintings sparkle. When deciphered they activate a complex codification of referents that send her works spinning into the orbits of feminist theory, criticality, and revisionist historiography. Each work, part of a chain of association and visual linguistics, is rendered by an artist who is palpably looking at art all the time. Wide spans of art history are devoured and requisitioned to create new nebulae of worlds that mirror, distort, and amplify our own, drawing on her experiences. With each work, she is forcibly inserting herself into a tradition of painting that has relegated women to the sidelines for centuries, and a system of legitimation that continues to make the labor of women art workers invisible.

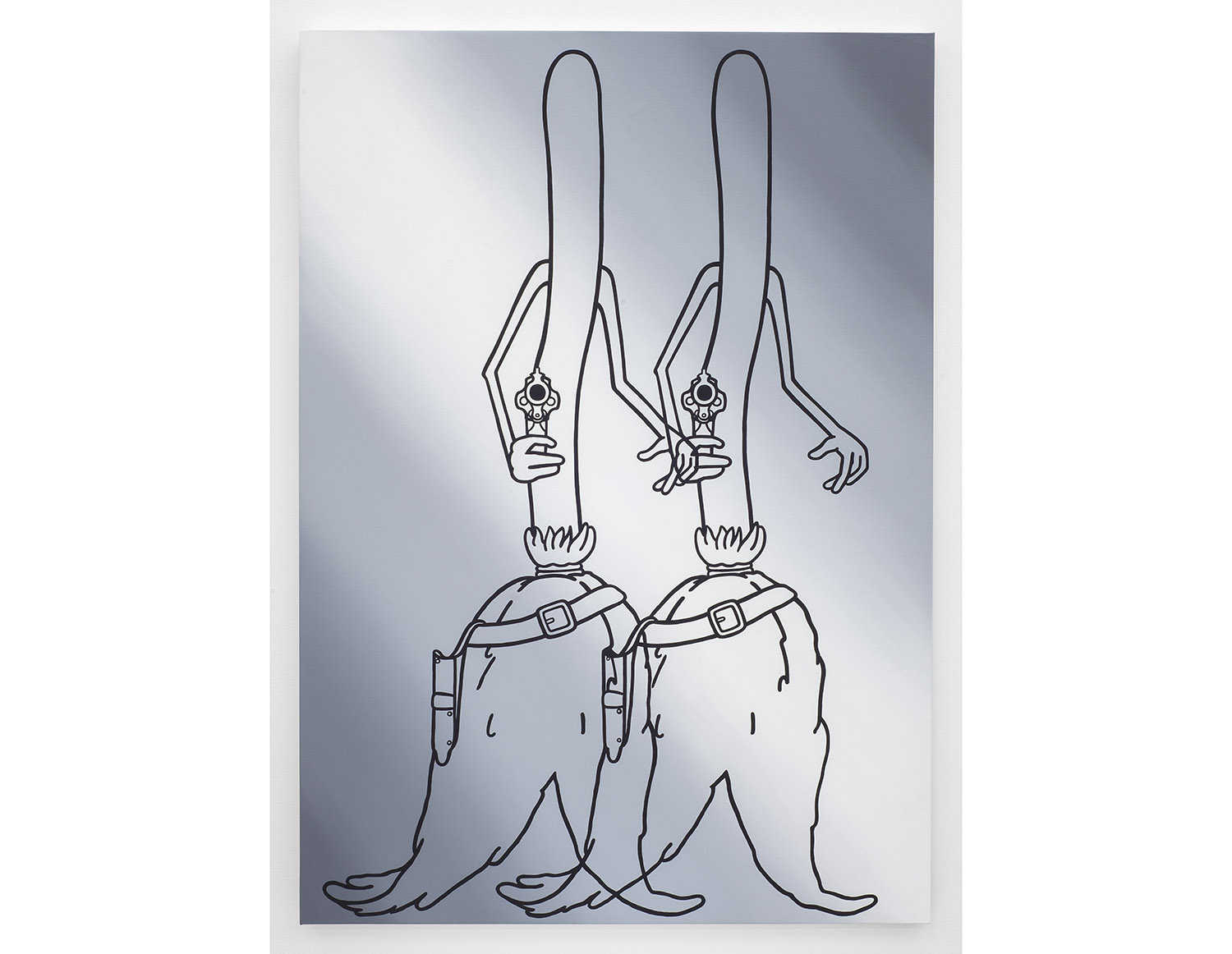

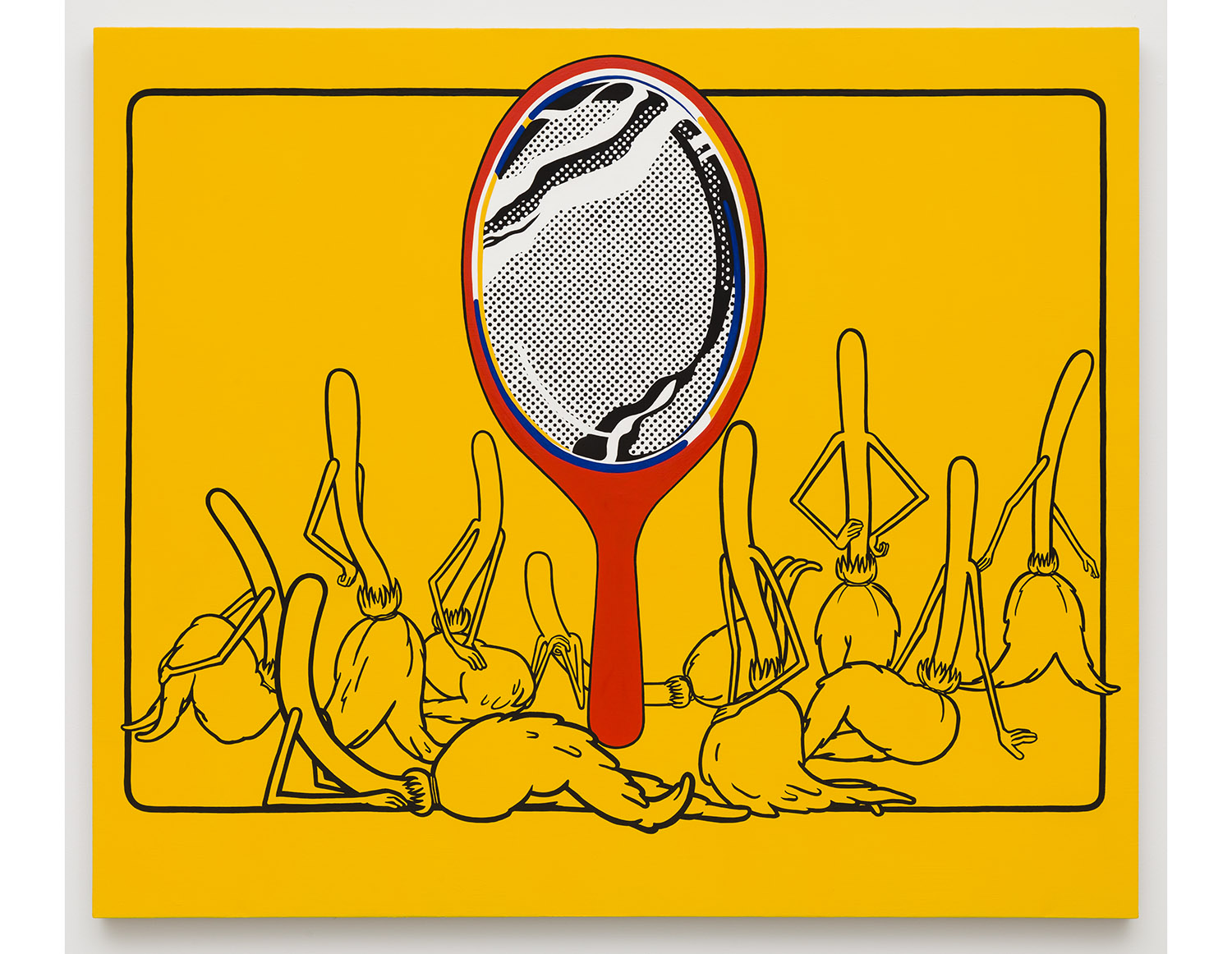

There is a certain pleasure in recognizing the wry references in her work, and seeing how she has skewed and reworked these according to her own personal constellation of signifiers. Many of her works make specific reference — through forms or style — to Pop art. Honest Espionage (2016) invokes Andy Warhol’s gunslinging Elvis 2 Times (1963), substituting the phallic power of the original for a cartoon broom (whose symbology we will return to later). Or consider The Mirror (2015), which features a Roy Lichtenstein-esque stippled mirror, a blank form reflecting nothing back at the viewer — one of many reflections, side looks, echoes, and refusals that populate her work. The slick irony of Pop art is present in many of her canvases, particularly its contact with the commodity as a form and art’s entanglement within that matrix. But Smith enters into this boy’s club with an intent to disrupt the smooth continuum of the sanctioned art chronology and to repurpose the styles of yesteryear, remixed to critique the power structures that continue to lionize hero male artists.

When first encountering her work I was particularly struck by her relationship to the Chicago Imagists, a group of artists working in the 1960s and ’70s, and the product of the Art Institute of Chicago. Exhibiting in various groups — the Hairy Who, Nonplussed Some, and False Image — at the Hyde Park Art Center, their aesthetic drew from comic books, non-Western art, pinball machines, the thrift stores and markets of the city, and the urban fabric of Chicago. Unlike the Pop artists who dominated at the time, their work held less irony and took up these references as legitimate visual languages that collapsed the distances between low and high art. Working across painting, printmaking, and sculpture, the artists crafted fantastic (largely figurative) images that deciphered contemporary life in the USA. Their work, for all its “low” culture referents, was incredibly highly wrought and practiced, an ethic that is similarly felt in Smith’s work, which is brought forth with absolute craft. Painstakingly applied almost-translucent layers of oil hold the light and bring forth deep pools of saturated color and smooth forms. Feats of painting such as rendering the surface of moving water, or light reflecting off an ice cube, are replete, demonstrating the dexterity of her painterly practice.

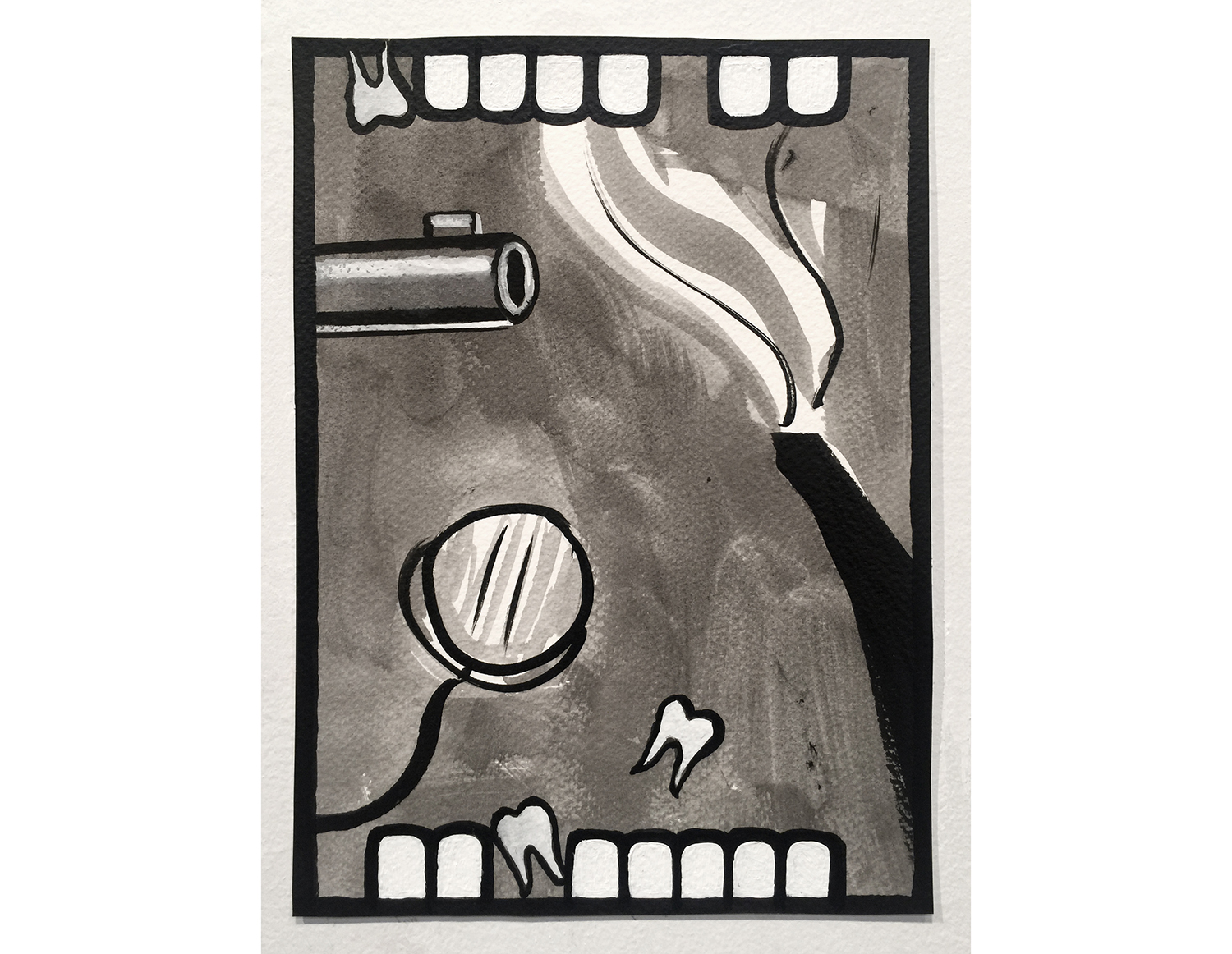

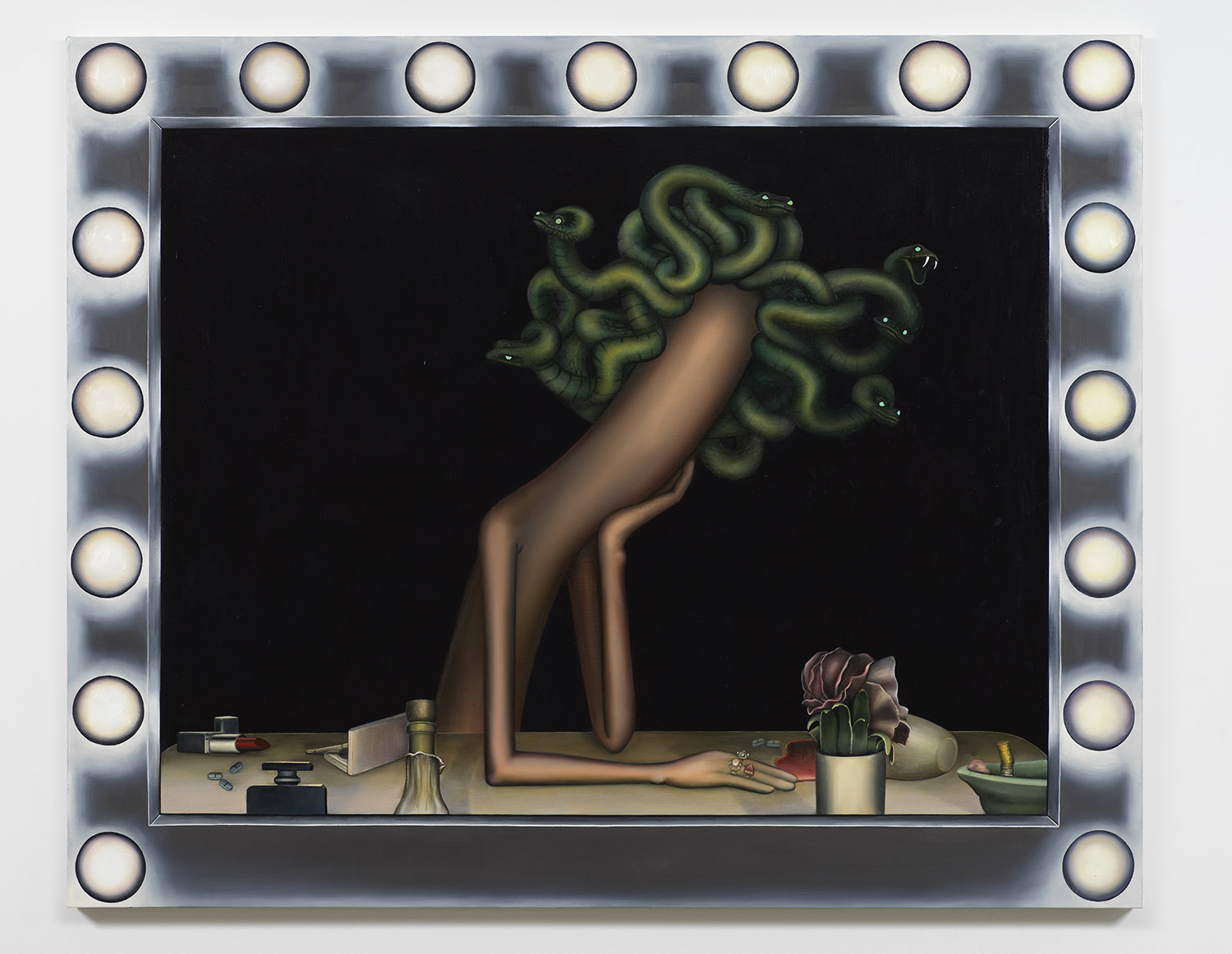

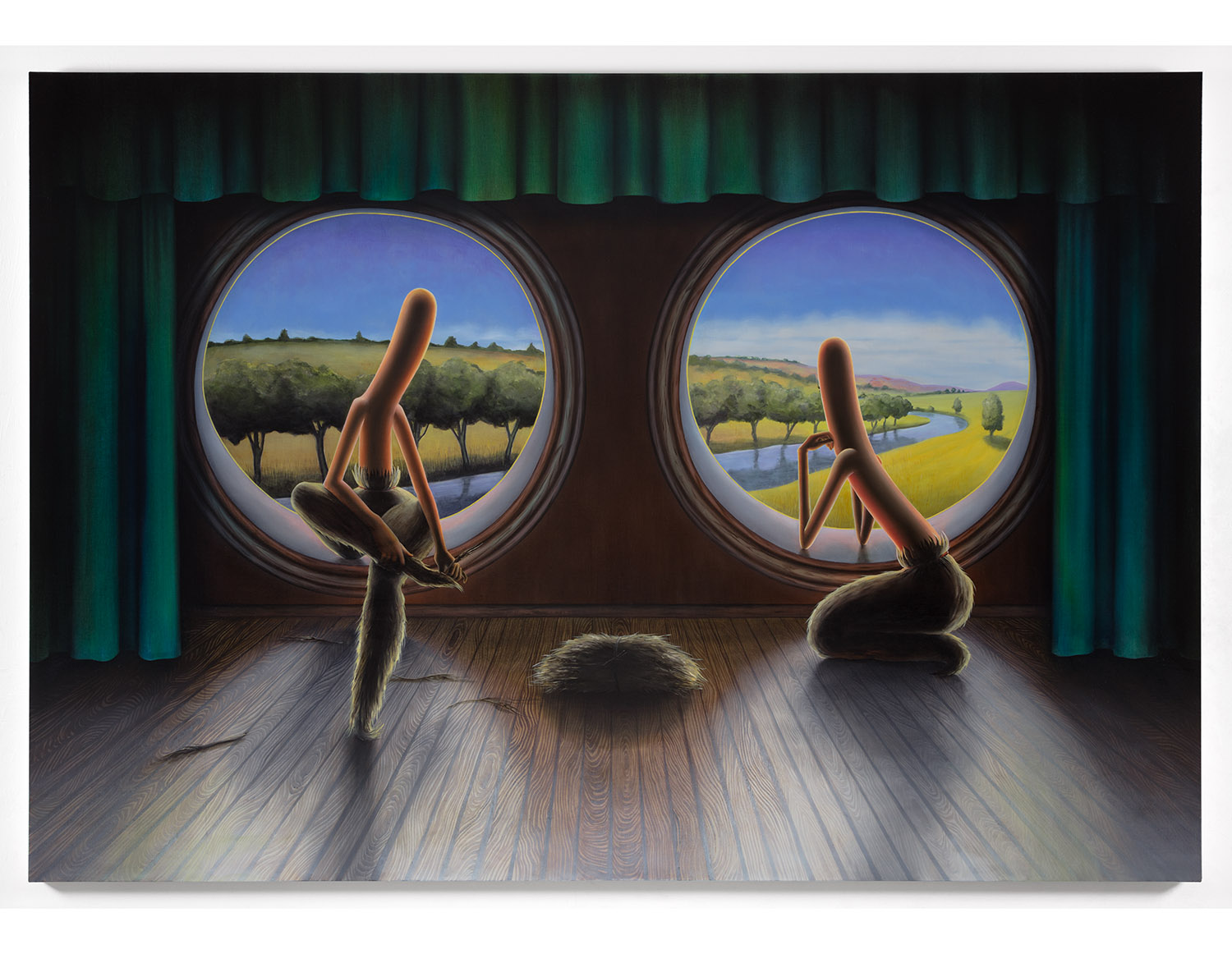

The gradients of Imagist Roger Brown’s curvilinear forms are strongly suggested in Mae Smith’s work: his smoking pipes (like her smoking guns), melting roads that sag in the pictorial frame, stages and curtains, and de Chirico-inspired architecturally framed vistas. Also Art Green, whose paintings often feature doors and apertures, proscenium arches looking to spaces beyond, presenting a frame within a frame, are reminiscent of the gaping mouths that frame Mae Smith’s Devouring Saturn (2018), The Discipline (2016), a back-stage make up mirror in Medusa Moderne (2018), or the eyehole-like windows of Brooms with a View (2019).

The latter falls in with the Imagist tendency for titling works through word play, slips of the tongue. Another Imagist, Christina Ramberg, is directly summoned in Smith’s Heretic Lace (2019). Ramberg, one of many women in the Imagist circle, made thousands of sketches of lingerie catalogues, and her canvases present ever-more-abstracted visions of limbs and torsos encased in lace and lashed into corsetry. The genus of this focus was the memory of watching her mother getting ready for a night out with her father, lacing herself into a girdle and affixing suspenders. She realized the extent to which women alter their bodies to fit into a male sense of what is erotic and desirable. Implicitly, rather than explicitly feminist, Ramberg’s work explores the fetishized female body, formed for the male gaze. This figure becomes increasingly dismembered, fragmented, and objectified. In Heretic LaceSmith has taken a twist on Ramberg. The image is a zoomed-in view of a suspender-strapped leg, a black stocking with a mouse motif, and a slice of thigh. The pattern is taken from a nineteenth-century wallpaper design, and corresponds with the invention of capitalism and colonialism. Rats consuming wheat are representative of the ways in which some consume the medium of painting. Smith positions herself as the rat, the unwelcome female presence in the august halls of the painterly academy.

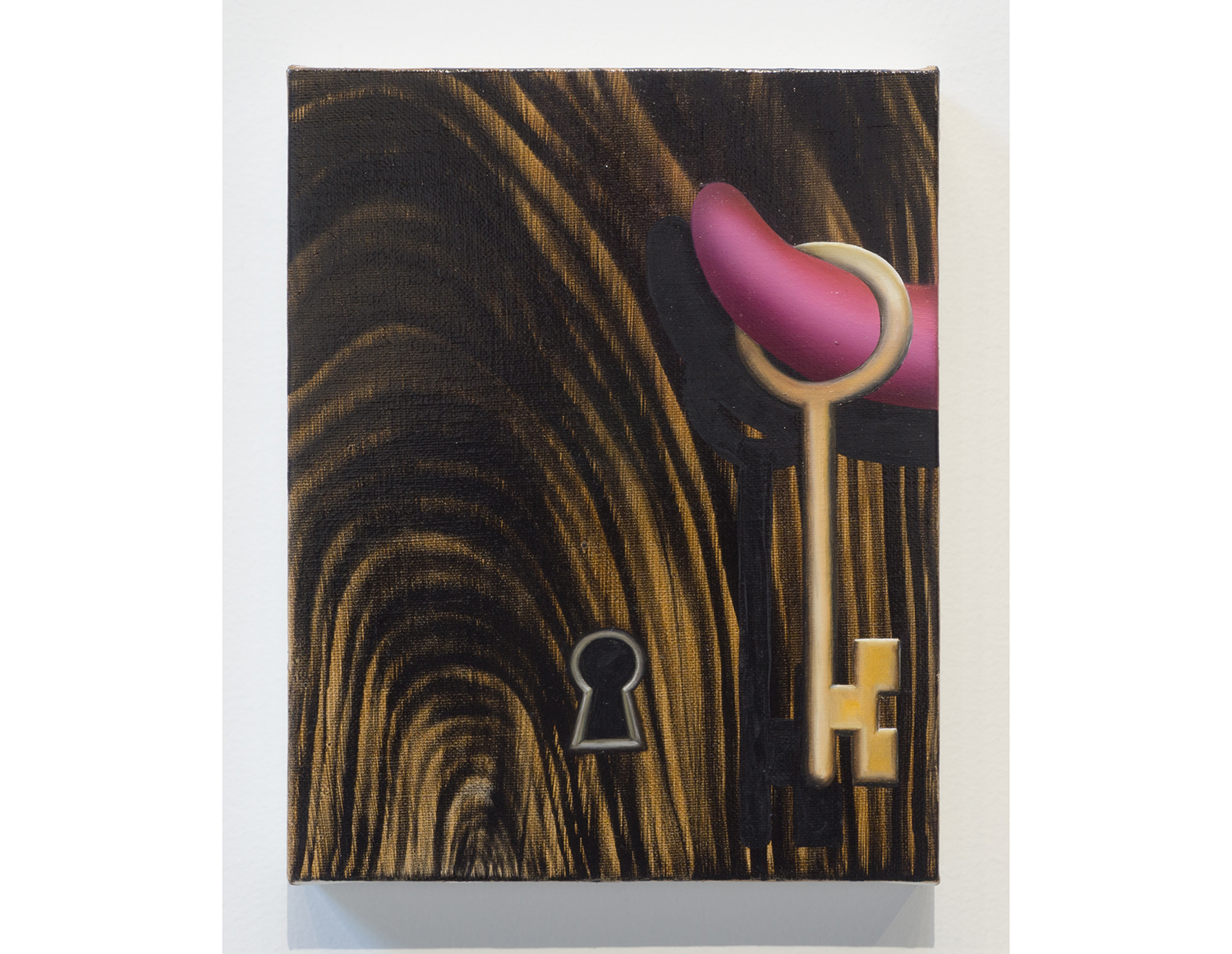

The most dominant reoccurring motif, or even avatar, in Smith’s work is undoubtedly the broom, appropriated from Disney’s Fantasia (1940). “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” section of the animation features a broom that comes to life to endlessly serve its creator. The botched spell replicates the broom ad infinitum, and its labor spirals out of the apprentice’s control. (It’s a nice thought that Smith’s paintings in their replication over the years are perhaps spiraling somehow beyond and out of her control.) She has described how the broom appealed also as a symbol of domestic labor, predominantly within the female sphere, and as a visual conceit on the paintbrush — Smith’s tool for her own labor. I’d perhaps add the absent referent of the witch — a female figure whose creativity has historically been violently repressed by society.

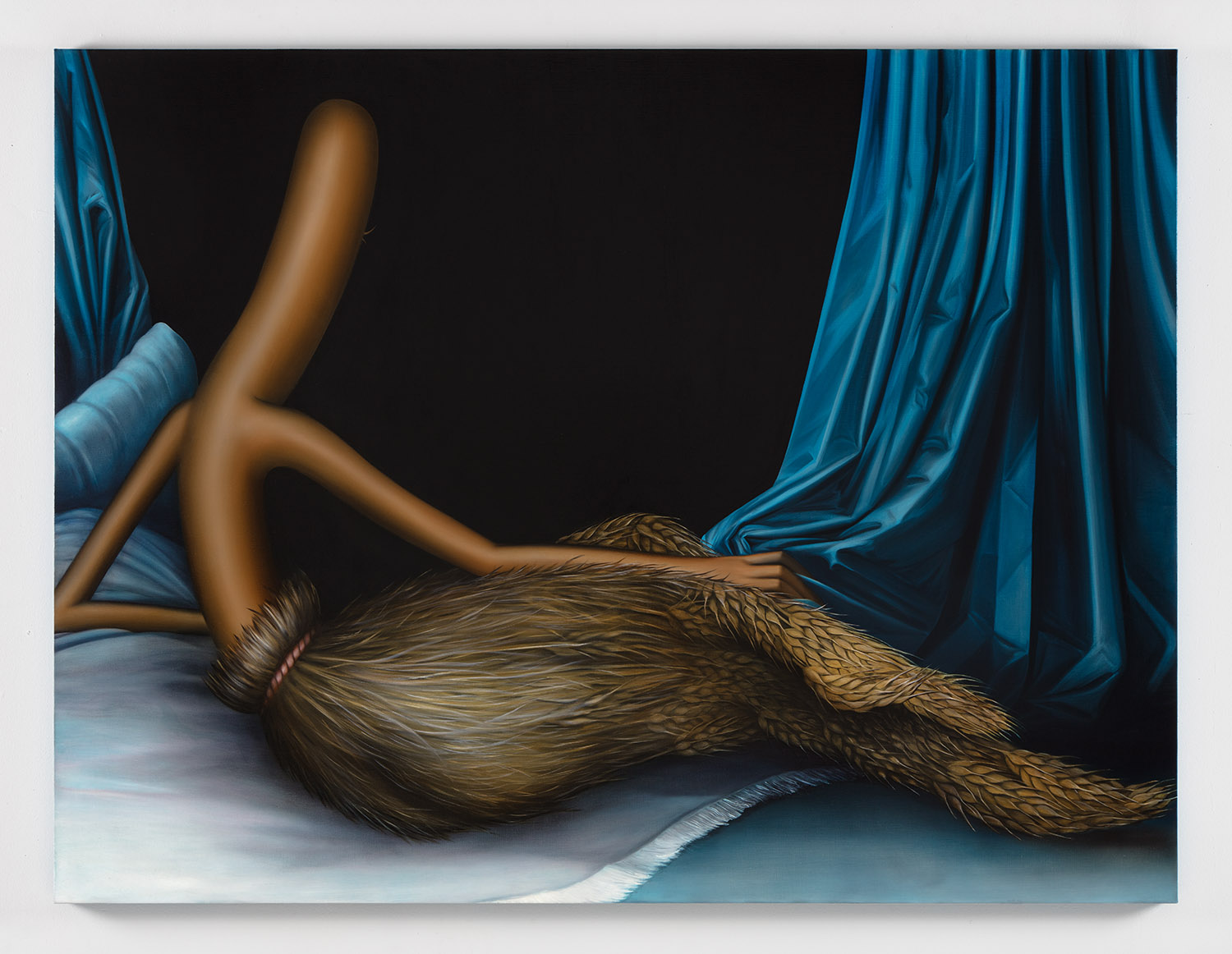

Formally, the figure of the broom allows Smith to represent the female body while avoiding the same traps of representation that she wishes to trouble within the canon of Western art history. Gone are the loci of lust, objectification, veneration, and hierarchies of power. Instead the figure humorously steps into the poses of art history — perhaps no more directly than in Gleaner Odalisque (2019), where Smith engages with the lush Orientalist fantasy rendered by Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres in 1814. In her version, the same heavy blue curtains frame a recumbent figure, this time a broom, elegantly at semi-repose, reaching down to the wheat-like ends of “her” body. In titling the work the “gleaner” Smith links the broom character to those women who would follow the harvester picking up the ears of corn left behind. Smith points thus to the role of the artist, picking up the leftovers of contemporary culture and art history, and morphing them into something new. Her gleaner is a similar figure to that of the rag picker, as described by Walter Benjamin, who would move through the city gathering fragments of discarded things, putting them together to create new readings of those fragments in the form of history. For Emily Mae Smith these are firmly bound together to create her story.

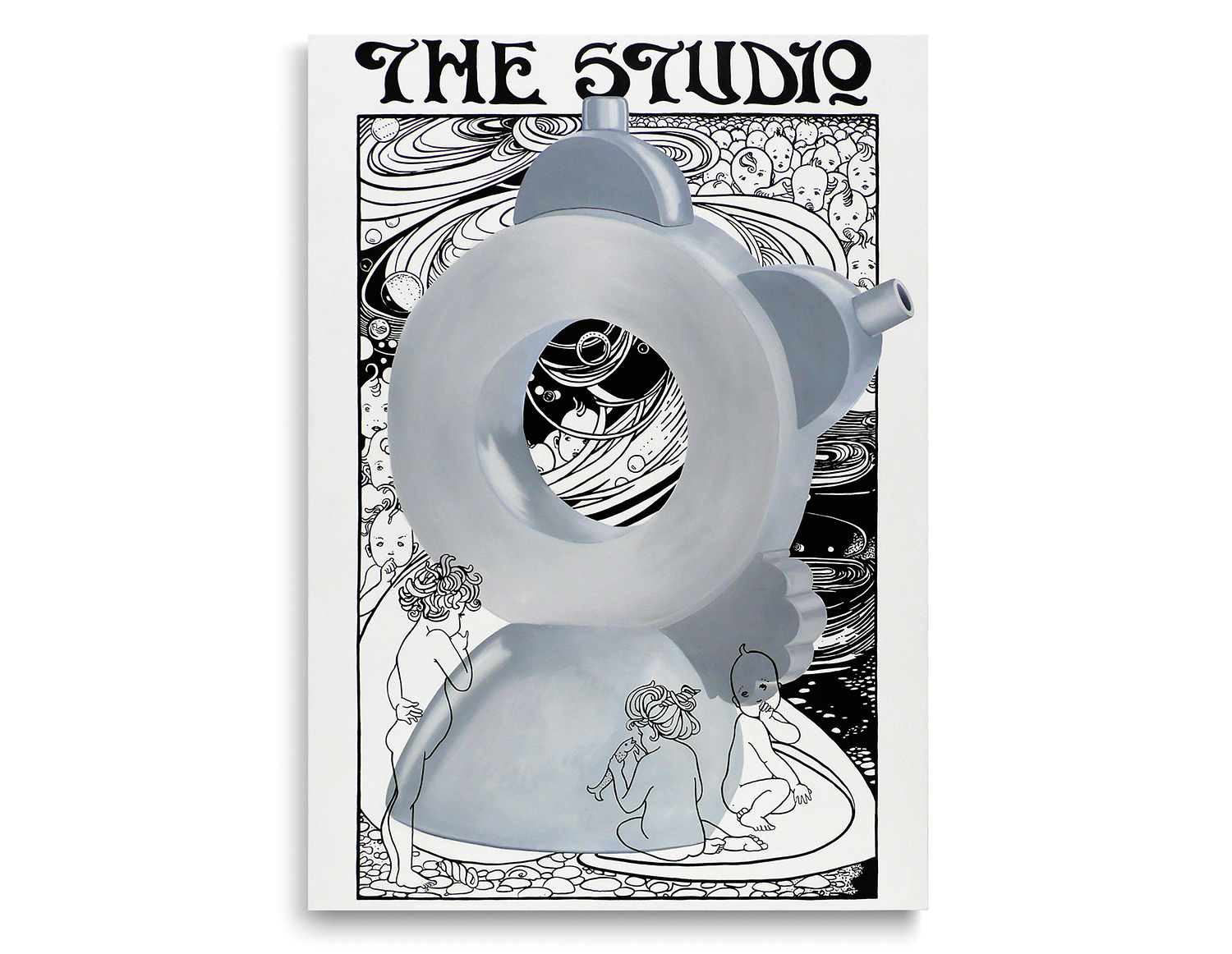

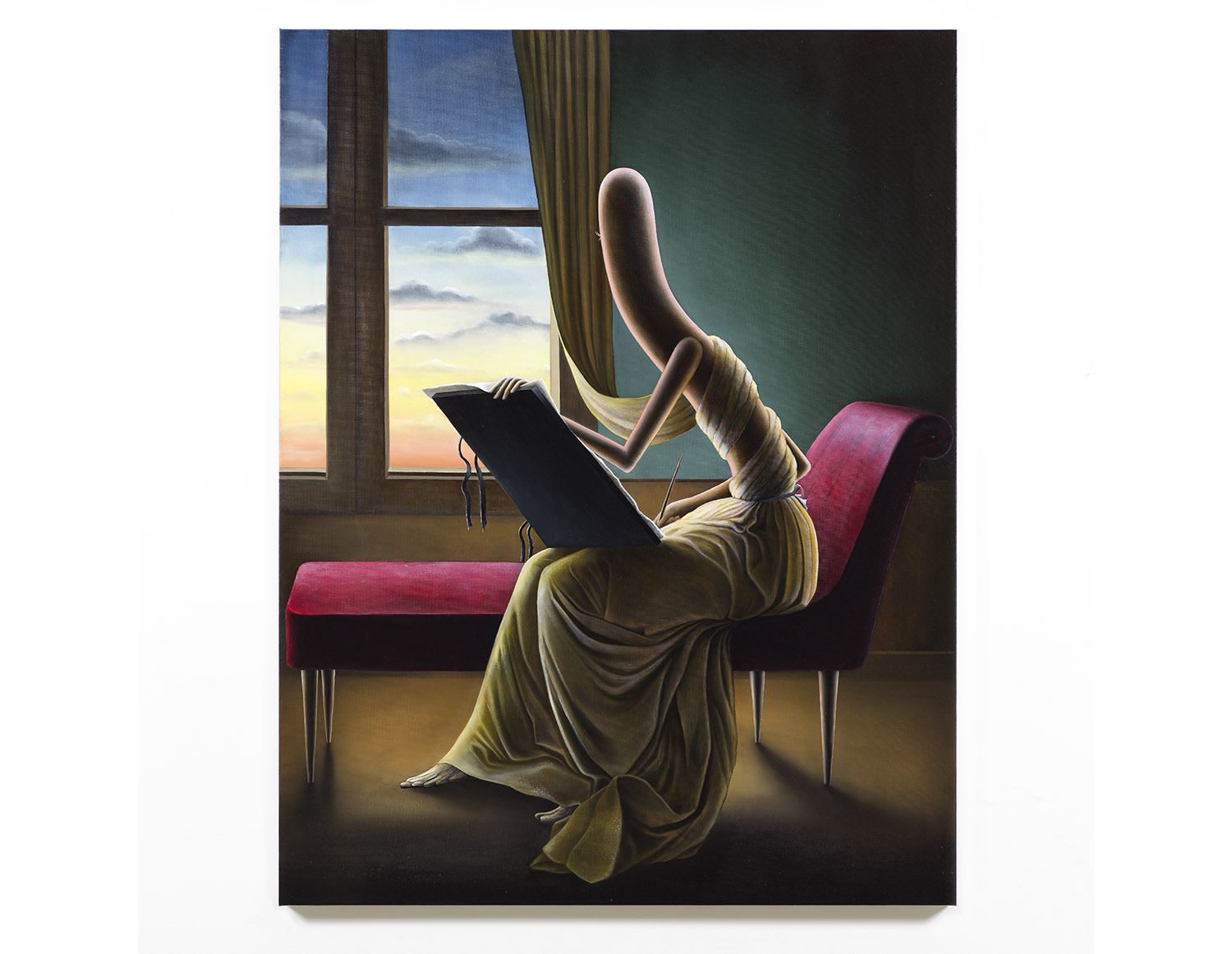

Many of her paintings engage with what it is to be an artist, a female artist, and a painter. The Drawing Room (2018) draws directly on a 1801 painting by Marie-Denise Villers — a work that was misattributed to Jacques-Louis David until the mid-1960s. A broom sits drawing, rendered herself through a female artist’s labor. Spitting Image (2019) is an even more striking image in this regard. A broom figure sits in front of a mirror painting what is probably a self-portrait. The broom is turned to face the mirror; a graphically rendered mouth gapes in what could be a scream, a grimace, or a smile. Is this an existential crisis, a gesture toward the almost insurmountable barriers between selfhood, artistry, and society? A shrill cry from the isolation of the studio, at the enormity of the task of rendering image to canvas? It expresses a brooding darkness that lingers behind the laughter in much of Smith’s imaginary: gaping mouths, tongues sliced on buzz saws, fruit prickled with spines landing on flesh, snakes wrapped around empty hourglasses. Piquant pictures that project out of the frame to elicit visceral responses in the viewer, a simultaneous discomfort and attraction. Her lexicon combines to create motifs of a curdled consumer culture. Visions of an emptied-out and reformulated femininity that won’t sell goods but could if she wanted it to. A laughing and slow seductive thrall to death, annihilation, decay: memento mori for our century.