Grace Wales Bonner: I just came back from Germany; I was there with Adidas. The show in Paris was really special, and everything flowed beautifully. I think there’s been a good energy coming into the new year.

Duval Timothy: Can I ask you about the Adidas collaboration? It’s interesting, as I guess there’s an opportunity for more accessibility to your work. How do you feel about that?

GWB Yes, I think about influencing culture on a different level, and the partnership creates more possibilities and opens what can be embodied and what can become a vessel. I find it quite powerful that a message can be transmitted through a product. There are different ways for a message to be communicated, and I feel like there’s something rewarding about the work being more accessible. It has been interesting; the project has a life of its own.

DT It doesn’t happen very often, but sometimes you see someone with, for example, a tote bag, and I get this electric feeling of just things existing and being taken up by people in the world. It kind of charges me up. So, I guess you must have felt that a lot. I was reading the supporting text in that record you put me onto, Biluka y Los Canibales, Leaf-Playing in Quito, 1960–1965, and that idea of cannibalizing a thing is exciting to me. People taking up traditional items and messing with them is such a compelling concept.

GWB Yes, I think sometimes I am attracted to classicism or some kind of framework, and thinking about how you can disrupt that formality from within — this feels like the way I am drawn to operate. Understanding the lines and then how to vibrate within a space creates more possibilities and opens something up from that place. What I find really special about you is seeing how consciously you approach things. Your process feels so thoughtful and considered, and you reflect a holistic way of living and creating work. I am intrigued by how you think about time. I noticed that you also seem to have moments where you’re focusing on production and then moments where you pivot to reflection. I wonder how you build time to support your creativity?

DT In practical terms, I feel like it’s a bit of a battle. I feel like I’m almost at war to make space for that time and protect it in terms of attention and disconnecting from technology. But then also, the concept of a residency naturally became a thing in my life through travel. Generally, I started to notice that most of the meaningful experiences in my life, as well as bigger things that became art projects or creative projects, came from traveling and spending time with people in places. Part of that is the disconnection of everything else, which gives you the space to create more and be present with everything in that context. The people, the history, and just generally your relationship to all that is there. I think that for many people, reflecting on the most memorable times in their lives, they’ve gone off somewhere with other people. In 2020, during the pandemic, I did a residency in Spoleto, Italy, at the Mahler & LeWitt Studios. It was the first time I did an actual residency. And then, I started to think of how I could implement that in my own life with Sierra Leone, having a home and studio there, and just going every year and creating. It feels like a constant. I don’t know if you feel the same way in terms of having to build space. I guess I’ve been releasing many projects consistently, but I maybe don’t have as much of a schedule. How do you feel about that with the fashion cycle? It’s a lot.

GWB I think about different rhythms of work and the fashion system. I do two collections a year, which is probably the least you could do in my field. I understand what can be done within those parameters and the limitations within those parameters. That’s one productive cycle, and I need that kind of energy, rhythm, and structure. I also understand that there are certain projects that require a very different sense of time and development. For example, working on “Spirit Movers” at MoMA was a three-year development and had a very different pace to the development. I like to understand certain rhythms but then also have varying paces. I have quite a distant vision. And I feel like playing with time; I think about the overlapping of the present, past, and future. That’s a place I’m interested in engaging with creatively.

DT Yes, I guess spending time with concepts is gripping too because good ideas persist, they don’t go anywhere, or they last the scrutiny of time.

GWB It’s fascinating, a consistent practice of pouring intentionality into something over time. Working on the MoMA exhibition consisted of regular intervals of thoughtful reflection and consideration — that kind of accumulation and intentionality becomes imbued in an experience. There’s something amazing about reflecting on an idea over an extended period and all of that work being transmitted in the final encounter.

DT I also think there’s something in the lives people lived before; I feel like we leave things behind that are almost waiting to be picked up because there’s so much research behind the practice. I like the idea of developing, carrying the baton, and continuing other people’s work or acknowledging the impact of it, which I’m thinking about a lot with this project and in my music. I guess everything doesn’t exist in voids, and I’m trying to respectfully take from all these people that influence me and use it to hopefully do something slightly new.

GWB That’s amazing. Last year, when we were speaking about working on music for the Autumn/Winter 2023 show, you seemed to be almost creating new work every day and in quite a reflective state of production. Are you still producing in that way?

DT Not so much right now. When we started discussing this project, I began playing every day, recording new bits, and trying to create a new composition to center the whole thing. But having a daughter has been disruptive in a great way, and that’s come to the foreground in terms of managing time and setting up a recording space and moments for that. But I also found that maybe I don’t have to make something new entirely. I can push something further and actually sit on one idea and particularly work on the performative element. There’s also a sense of endurance and rhythm in the whole exhibition or the works in the show you put together. That’s something I’ve thought about a lot, and I realize I haven’t created that much work that speaks to that. So, I’m really eager to establish a strong foundation and then push that single aspect a bit further. But life is funny: I feel like when I’m not working, when I’m not recording music daily (which happens for periods), the downtime contributes a lot to when I’m doing that again. When you come back to something, do you feel you have fresh eyes?

GWB I can connect to what you’re thinking about in terms of taking up the baton, reengaging with an idea, and carrying it forward. I feel like there’s been enough time now since I started my brand — it’s coming up to ten years next year — that I’m able to look back at early intentions and feel comfortable again to reengage them with a new sensibility that I have gained from refining what I do over the years. I feel like you operate in quite a unique space and cross over into different worlds. Do you approach things differently in the music industry in terms of how you proceed with production in comparison to your artistic practice, or is it all one thing?

DT I feel like they’re different, and the differences are what’s charismatic to each discipline. Although I think there are things that obviously unify. I always feel like I’m painting, which is what I originally studied, and I had this particular palette or use of color that I love, and I feel like I’m doing that the way I play piano. Music has this amazing universality and accessibility, so many people are familiar and comfortable with it. Music is almost like a friend. I enjoy that with most music, people know when they love it and when they don’t.

GWB That’s really interesting.

DT But things coming together is interesting to me, too. Another thing I wanted to talk to you about was your clothes. When I’m wearing some of your clothes, I have these little moments where things click with me. There are little quirks in your garments that have a familiarity you recognize or experience that comes from our culture, and there’s almost a reassurance in how you bring those things forward. Recently, I was thinking about how, around the corner from where I grew up, there was a big old Victorian mansion, which was owned by a Jamaican guy called Mr. Pink. He had this large flower garden outside the front and painted the whole house in really vivid colors, and he’d wear a straw hat or outlandish clothes and almost bark at people going by. It’s funny; I grew up near this house, and a lot of people would say Mr. Pink was crazy. I’ve always found that building interesting. And then, many years later, film director Helena Appio made a documentary about him and his house. When I saw it, I was in Sierra Leone, and I had these moments of recognition: that’s our culture, and that’s what we do.

What I’ve done in Sierra Leone, painting my house blue, comes from that. In the documentary, Mr. Pink talks about how he was making his Jamaica there, in London. But it was funny that it kind of took Appio making the documentary for all these things to come together and click in this magical way. I feel like this about a lot of your work, and I was wondering if you ever have some of those moments.

GWB It’s really captivating you say that, especially thinking about color. When I was younger I felt like I was choosing this path and making these creative decisions and having this quite specific taste and perspective. But then, over time, it kind of revealed itself that a lot of what I’m attracted to, drawn to, is something I’ve seen before. But it’s also something my ancestors have seen before, and there are certain colors and things that you might feel are “you,” but you’re actually kind of recollecting something from another time. Recently, I felt this more strongly. Last year, I was in Jamaica and on the Rio Grande, and there was a really specific rust-colored berry on the trees, but everything around it was green. That color is so distinctive because it is the only intense color you’re seeing.

DT It popped out.

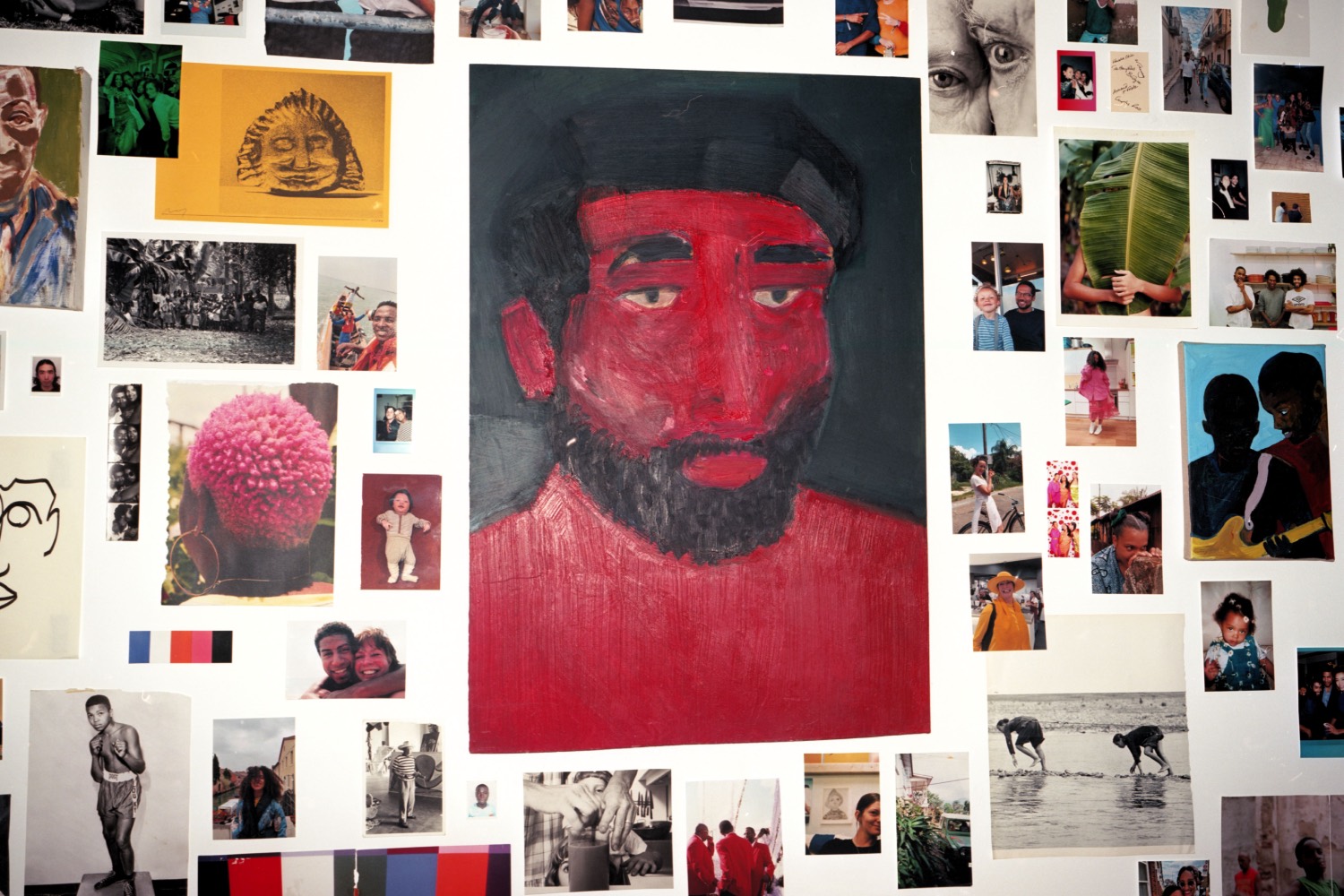

GWB Exactly. And then I’ve always been drawn to this kind of rust color in design as well. I think there’s something really powerful in what you’re drawn to and what you inherit in terms of aesthetic experience. I was talking to a friend about this, and he was saying there’s a word for when you see something your ancestors saw. It’s like a déjà vu but from another life. It’s dynamic, and I feel like the creative act, or for me, being in my purest expression, is probably researching and putting different things in dialogue with each other. But I also realized that this process of collaging worlds and imagery had come from me attempting to piece together a landscape that I was familiar with or even a landscape that my grandparents were familiar with. So, growing up in London, I used to do collages with photographs as well. And I realized I was very drawn to a specific type of terrain and environment, and I was using photography to piece together a sense of place. So, you use the means you have around you to connect, which is interesting because there’s an idea that you are being guided.

DT Yes, that’s wicked working it out. The way my mind works, I’m not very good at recalling information. I love finding out things and feel like I internalize and learn from them, but I’m not good at articulating facts or what something means. I always think what people call a “gut feeling” is actually a subconscious intellectual thing. Some of us don’t have the bandwidth to regurgitate it vocally. I feel it’s important to trust a gut feeling, to go with something without knowing where it comes from or what it means. And a lot of the time, we find out later, like you’re saying, realizing where that comes from.

GWB You worked on some music for my Autumn/Winter 2023 show, “Twilight Reverie,” and I just wondered how you relate to a certain visual world and story. When you create, are you visual in terms of what you’re translating sonically, or which comes first?

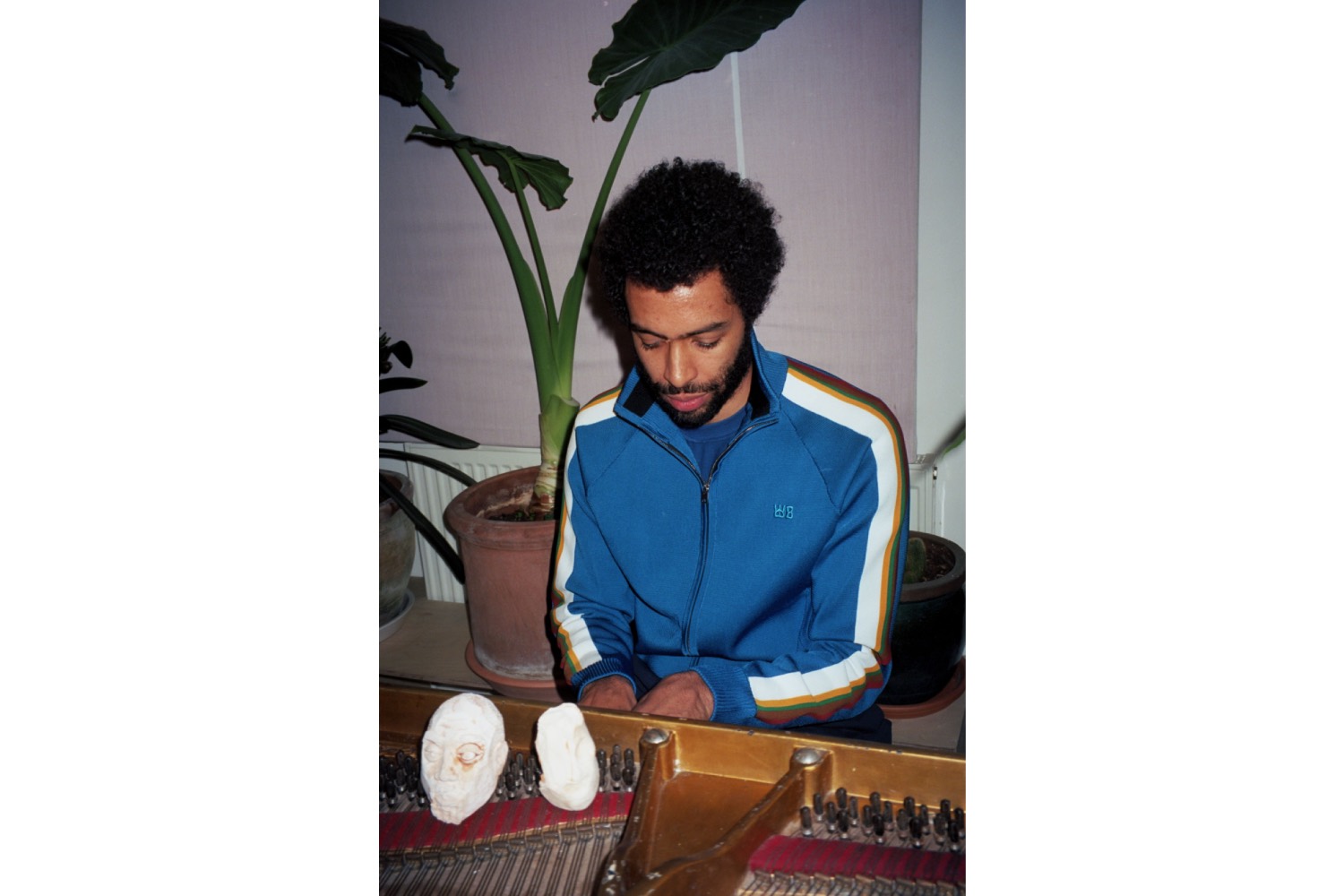

DT Yes, sometimes I can kind of see something, or it’s almost like a visual I’m trying to recreate sonically. I’ve got this track that hasn’t come out yet that I made during the residency after I freaked out one night. I went for a midnight walk and was thinking about leaving. I was having this crisis and sat on a hillside slope under the moon. It was a full moon, and the whole thing was a kind of amazing, distressing moment. There was something about the moonlight and the texture on the slope I was sitting on, which was made of dusty stones and shrubbery. That was a moment and a visual feeling that I’m still trying to recreate sonically. Sometimes, that happens, and when I was working on your collection in Paris, I made a mood board of some of your work. And then those few conversations we had, that was more of a musical feeling I was trying to evoke. I guess it’s textural as well, like the prepared piano stuff, which we’re also continuing now; there’s something I was trying to recreate again. There’s an attractive regal quality to some of your formal wear that reminds me of more solid textures, like stone and metal, and those sounds felt appropriate.

GWB Yeah, I’m definitely responding to quite a percussive, metallic, sonorous world. Something kind of magical. And I think the exhibition at MoMA also touches on that. It’s the suggestion of a sonic potential.

DT I think those textures are really acoustic in that they’re not perfect. There’s something distinct about a sound that’s not like the room it’s recorded in or the texture of the leaf playing. It’s the sound of that leaf.