Statue of a Seated Woman, the Penelope Type (Early Roman Imperial Age). Courtesy of Musei Vaticani, Vatican City.

Two recent exhibitions have invited a reconsideration of the institutional narratives associated with the scientific discipline of archaeology: Christodoulos Panayiotou’s “Two Days after Forever,” hosted by the Cyprus Pavilion at the 56th Biennale di Venezia; and the “twin” exhibitions “Serial Classic” and “Portable Classic,” co-curated by Salvatore Settis and held at the Milan and Venice venues of the Fondazione Prada. In the conversation that follows, Panayiotou and Settis contemplate the authority of ancient art and the many challenges that a political understanding of archaeology can pose.

Christodoulos Panayiotou: In the exhibition “Serial Classic” we are presented with a number of copies of Myron’s Discobolus, yet we are more or less conscious that we might never get to see the original, today considered “lost.” The show also includes the Torso and Right Hand of a Statue of Penelope from 450 B.C., which was unexpectedly found in recent years, providing a different understanding of the seriality it propagated.

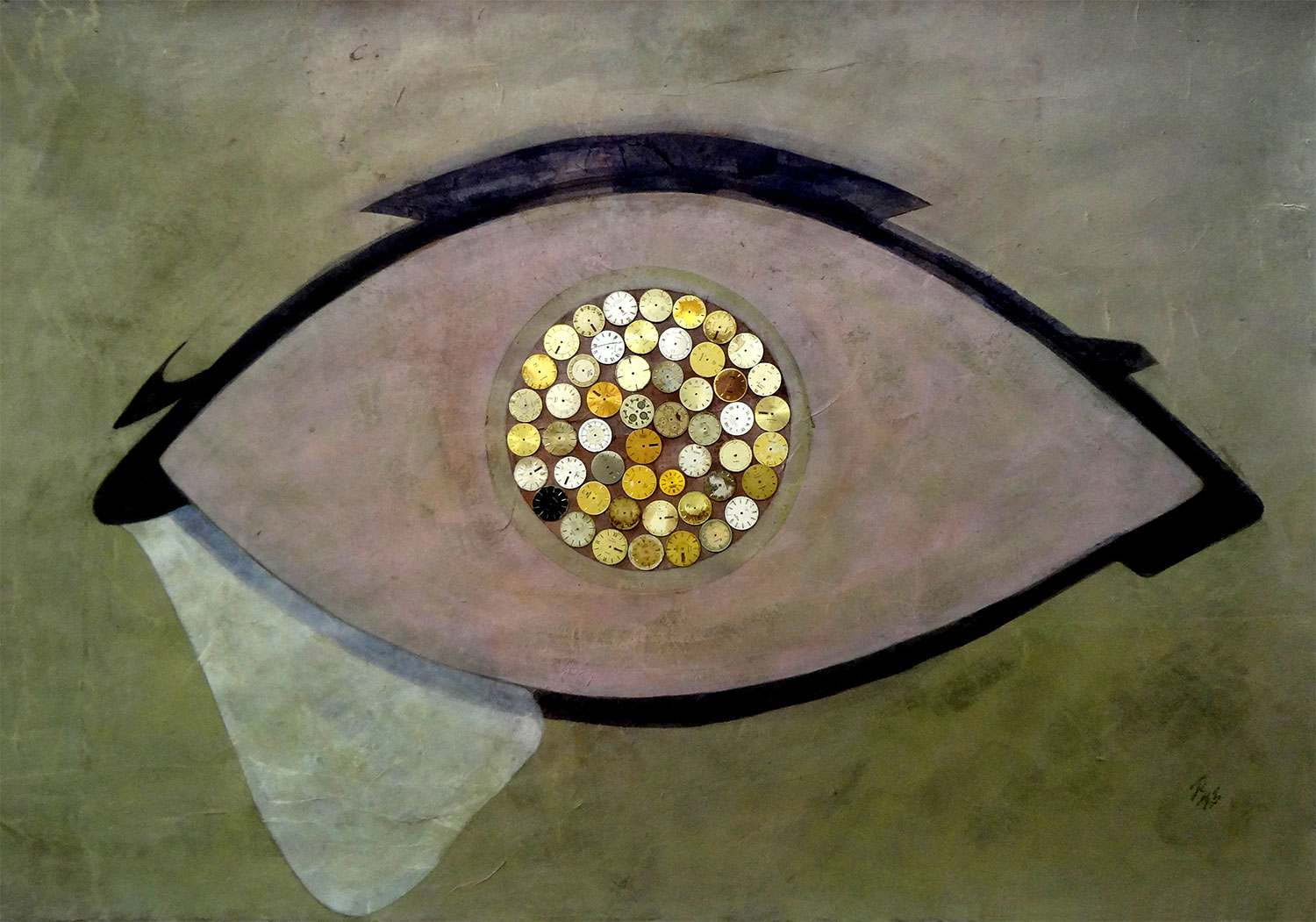

It seems to me that archeology, either through laborious excavations or interpretive speculations — on what is forever “lost” and what is to be found — is primarily driven by the desire for the original. What I find peculiarly fascinating in this exhibition is that it does exactly the opposite: it dissects this desire and takes the perpetual reappearance of specific forms to be a new analytical line between lapses, successions and absences.

Salvatore Settis: Archeology is a “scientific” discipline, but it basically concerns the attention between what is preserved and what is lost. As archaeologists, we deal with worlds — I refer here mainly to the Greek and the Roman worlds, but this is true for Mayan, Peruvian and Chinese archaeologies — that have been lost forever, and for which only parts can be recovered. From time to time, we register new discoveries; yet, what classical archaeology tries to do is to pull back together the fragments that we own so they make sense within a bigger hypothetical picture. Nevertheless, the fragments we own are only a very small percentage of what was created by ancient civilizations, so those always have to be interpreted with an awareness that more is lost than what is found.

Archaeology is a political practice, meaning that the exercise of collaging these fragments together and of interpreting them can be a learning experience for looking into the present, which is an equally fragmented time. I believe this is one of the reasons why many contemporary artists are thinking in archeological terms: they look at the past not in a nostalgic way, but as a cognitive device.

CP: There are different tensions at play in contemporary art; nostalgia, as an esthetic exercise, remains a big part of it. But beyond the caricatures of the past, archaeology can serve as a possibility to reexamine our vicious cycles of oblivion. Personally, what I am sensitive to is how time gets dynamically amplified through archeological processes — how a reconstructed past is projected into a speculative future. In this sense, archeology carries the uncontested responsibility for conservation and becomes an authority for narrating not only the past but also the future — taking for granted that future civilizations will be interested in these artifacts. All that very strongly positions our sense of the present — our fragmented present, as you say.

However, I come from a culture in which archeology has often been used as a political and ideological instrument, a sort of natural illustration for the validation of hegemonic political narrations. That of national continuity for instance, which connects us to whatever we desire to be connected and disconnects us from the rest.

SS: Let me clarify that when I speak about archeology as a political practice, of course I don’t think about the political use of archeology. In this respect Italy has a very bad record, such as Mussolini’s reliance on the model of the Roman Empire for legitimizing the Italian colonization of Libya and the Dodecanese, and supposedly other places on the Mediterranean Sea — the mare nostrum…

I rather think about a practice of archeology that doesn’t take interpretation for granted, but makes interpretation the outcome of a very long and sometimes painful process of assembling pieces. In this respect, by organizing the exhibitions “Serial Classic” and “Portable Classic” I aimed to offer a view of ancient art that was not based on its authority but on the challenges it poses. This intimated a reconsideration of the rhetorical narrative according to which Europe has emerged through Greek and Roman cultures. We are definitely very much like the Greeks and Romans, but more important is how different we are from them.

Think about Greek democracy — a concept that has been very resonant in recent political discussions. The word “democracy” is Greek, but Greek democracy doesn’t mirror our contemporary understanding of a democratic governmental system: Do we want slaves as in classical Athens? Do we want women not participating in political life? So the question is not whether our democracies are identical — because they are not. The real question is how is it possible that a civilization that approved of slavery produced such an incredible output of thought, poetry, theatre, art and so forth.

I think the most important lesson we have to learn from ancient civilizations is the sort of mental gymnastics it takes as we try to classify what is similar and what is not between our own world and theirs. In fact, if we appreciate the past in terms of a tension between the identical and the different, this is the best way to approach remote civilizations like China’s, for example.

CP: I certainly agree. Your approach does not rely upon the authoritarian uniqueness of the original. On the contrary, the idea of seriality that you propose stimulates a dynamic perception of time — a more horizontal and less vertical one. Here we face some sort of nexus-type of archeology.

SS: I think you are just understanding one very important point, which is to challenge the idea of a linear story whereby we descend from Greeks and through them we discover history and philosophy and medicine and democracy and, last but not least, the idea of art.

This self-consciousness can be challenged by just saying that what we know about our ancestors is so little — consider that we own less than ten percent of Greek literature! Sophocles wrote around ninety tragedies, but we inherited barely seven of them. We are very fortunate to have what we do, but whatever we say about Sophocles (or Aeschylus, or Euripides), we should be very aware that it is a conjecture, a speculation. This is a lesson — I was almost tempted to say “in humility,” but let’s just say a lesson — to acknowledge that what we know is so little. But this recognition should not discourage knowledge; on the contrary, it should stimulate us to grasp what we ignore in order to learn more about it.

CP: I would like to insist on the word “lost.” I think that “lost” is a word developing in a semantically problematic way, as it carries a heavy sort of desire: the desire to find again what has been lost. These lost parts extensively served the narrations of our nations as a method of ideological interpretation.

SS: The idea of archeology I have in mind is totally non-nationalist, because the very idea of nation was born millennia later than the things we are talking about.

CP: Yes, but somehow together with archeology as we know it today.

SS: I would say together with the rise of archeology as a scientific discipline — which can be said to have happened in Germany in the eighteenth century. But actually, I see archeology as a practice that emerged as a consequence of the antiquarianism born in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italy, a cultural context in which the idea of nation was totally absent. We usually believe that Winckelmann invented classical archeology, but this is not true because antiquarians were assembling ancient fragments — they were connecting the dots — long before his time.

Also, it has to be said that Winckelmann’s main research instrument was Cassiano dal Pozzo’s Museo Cartaceo, a collection of thousands of drawings, to which he was given access by working as a librarian in the library of Cardinal Albani, in Rome. Cassiano dal Pozzo was a seventeenth-century gentleman who commissioned the best artists of his time to make drawings of every single piece of classical antiquity: coins, sarcophagi, pots and so forth. Winckelmann worked with those reproductions, so his knowledge of classical art was based on a cultural project that was not even remotely “nationalistic.” Rather, dal Pozzo’s idea was to use classical antiquity as an encyclopedic framework to understand the world — a very cosmopolitan project indeed. Poussin was among the artists who worked for him.

So a way to contrast nationalistic archaeology is to show the truly cosmopolitan vision that laid the ground for Italian antiquarianism. Let me give you a further little detail. Along with the “paper museum” of Greek and Roman antiquities, dal Pozzo embarked on another enterprise: he had artists draw fruits, plants, flowers, etc. in order to classify them. So he intended to catalogue both the world’s cultural and natural output — he was driven by a pure universalistic ethos.

Nineteenth-century nationalism narrowed this vision. After the unification of Italy, political rhetoric insisted very much on the Roman legacy, while during classical antiquity forty percent of Italy was Greek. This fact was never denied — Italians have always been very proud of Paestum or Selinunte — but the mixture of Greek, Roman and Etruscan cultures fell into line with the edification of Italian identity.

Statue of a Seated Woman, the Penelope Type (Late Ist century A.D.). Courtesy of Musei Capitolini, Rome.

CP: I can see the two histories of archeology you are proposing, and I agree with your ideas around the invention and reinvention of antiquity. But archeology today remains a highly institutionalized and governmentally controlled practice that is intimately connected to power and the ceremonial expression of power. In Cyprus, for instance, the official history of Cypriot archeology rejects the antiquarianist tradition as despoilment. In that way, what preceded the Swedish Expedition, which took place in the late 1920s, is dismissed, and with it the very interesting — though problematic — practice of Luigi Palma di Cesnola, an adventurer who made a fortune dealing antiquities from Cyprus and thus became the first director of the Metropolitan Museum in New Work.

SS: I think that the main risk of classical archeology today is to remain within the boundaries of the discipline and to center everything around “new findings” — this is hard to believe, but it is very easy. If you look at archeological periodicals, you will mostly read articles telling about a newfound replica of the Crouching Venus, or a different chronology of the Praxiteles’s Pouring Satyr. That is fine, but what we need to recover is a sort of grand narrative that must be necessarily more appealing for our contemporaries. In this respect, we should insist on certain aspects — and seriality is only one of them — that look proper within contemporary time but foreign to the codified idea of the classical; but that, nonetheless, can be traced back, though in invariably different forms, to the classical world itself. This is a way of challenging the discipline by proposing new narratives, without creating a dramatic discontinuity but rather singling out elements that are already present in the discipline and privileging those that can lend themselves to further thoughts, in connection with contemporary taste and inclinations.

CP: I am up for new narratives. Since you mentioned Winckelmann, let me tell you one idea for a new narrative I had when I visited Trieste last year. I was accidentally there on June 8 and I stayed in the hotel where he was assassinated. On June 8, 1768, Winckelmann was brutally murdered by his supposed lover, Francesco Arcangeli, who stripped from him the gold medals that Maria Theresa of Austria had given him upon his visit to Vienna. Arcangeli was immediately arrested and judged guilty. He was executed soon after in an even more violent way than his murder. He was practically dismembered with the braking wheel — an ancient device of capital punishment, abandoned in Trieste during those times but specially restored for that case. It was immediately after I’d traveled to Rome, where I got to see the Belvedere Torso in the Museo Pio-Clementino in the Vatican. I could not help but connect the tragic story of the end of Winckelmann to his fascination with that mutilated ancient sculpture that became so significant in his work. The mode of execution of his murderer and that fragmented ancient statue became catalysts for a series of ideas leading to a new speculative biography of Winckelmann that I shared with an archeologist friend. He said I am crazy and that it is good that I am an artist and not an archeologist. I bet he is right.

SS: In a sense he is surely right; which doesn’t necessarily mean you, as an artist, are not free to follow your imagination. Indeed, nothing comes closer than classical, fragmented statues to the contemporary poetics of the “dismembered body” as seen in innumerable works by contemporary artists.

CP: Yet again, we have cases like that of the celebrated Japanese archeologist Shinichi Fujimura, who ended up admitting that he had falsified forty-two sites of Paleolithic interest, with great scientific impact. Had he not told anything before his death, the prehistoric research in Japan would have been completely different today.

SS: A story like this goes far beyond the mere reach of archaeology. Literary, documentary, historical falsification is a huge domain, whereby intuition, authentic knowledge of the past and forgery connect in a way that requires special attention from case to case. Whether such an activity can be classified as “art” only depends on our definition of what art is or should be.

CP: Well, what I am pointing out though is that these forgeries did not occur in the tradition of art, and Fujimura’s intentions were far from those of an artist. He was a leading archeologist and positioned his practice in the tradition of the science of archeology.

Furthermore, a recent work of mine came to my mind while seeing your exhibition. I believe it echoes your theories without having an obvious or a direct connection with archeology. It is a balletic variation that was performed every day within the Cyprus Pavilion by Jean Capeille (“The Death of Nikiya” from the Ballet La Bayadère, choreographed by Christodoulos Panayiotou, after Rudolf Nureyev, after Marius Petipa, 2015).

The choreography has a lot to do with two ideas that are very present in your text: one is the classical as a succession of movements, and the other one is the selection of those movements. In the text you also discuss the idea of mythography and how Greeks didn’t have a text, an official book that would freeze their myth. The mythographer’s work emerges when the myth stops activating itself and can be classified. I have the feeling that ballet is a very interesting discipline to draw from while looking into this junction — first of all because of its connection to archeology. I was discussing with Eike Wittrock — who is a brilliant ballet historian — how ancient statues, especially from the excavations of Pompeii, were initially interpreted as “dancers,” and how they inspired operas and ballets but also helped codify movements of the romantic style, in particular the quintessence of ballet: the arabesque.

Ballet, and dance in general, is a tradition that has never coined a popular method of annotation, even though many efforts were made in that direction. Today we perform romantic ballets, like Giselle for instance, through a form of seriality, which results in the embodiment of oral transmissions. Natalia Osipova, who beautifully performed Giselle last year at the Royal Ballet, and Marie Taglioni, who created that role in 1841, have certainly conveyed two completely different performances but which rely on the same forms and ideas.

SS: This is an extremely interesting point, first because it is about movement — I think the most vital characteristic of classical Greek sculpture is its suggested mobility. Second, because the importance of dance in Greek culture cannot be forgotten: it has a very critical role, especially in the Greek tragedy, which gathered poetry, music and dance together.

CP: Another interesting parallel can be established between the iconographic study of statues and dance: they both share the idea of an idealized pose. In contradiction of choreographic research in modern and contemporary dance, ballet remains a succession of ideal pauses that are put together in order to create movement. So if you have position A and position B, the movement from A to B will create dance.

That is why I considered the two Runners from the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum so moving in the context of your exhibition: they really re-create movement. They could be almost understood as pre-cinematic 3-D studies of movement reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge or Étienne-Jules Marey.

SS: I quoted in my essay a passage by Plutarch who said that the statues we look at are “remnants of ancient dances.” The statue is a frozen dancer, by definition. But its mobility doesn’t just refer to the body, but to the mind and to society as a whole.

CP: It is fascinating how what we consider ancient becomes double ancient through the projection of Plutarch. As if a statue could only be an exercise of memory or memorialization. On another note, I have a very long fascination with a sculpture of which you showed a plaster cast in the exhibition in Venice: the Barberini Faun. There is a speculation that Bernini completed the missing parts of the statue — he apparently added the hand that was afterwards removed and of which I saw a photo when I visited the Glyptothek in Munich. What about all the theories in archeology regarding missing limbs? I find the conflict between who was “pro completion” and who was against it very interesting. A sort of archeology of the non finito.

SS: There are two famous stories in this regard. The first is about the Belvedere Torso, which Michelangelo apparently refused to complete — for him, the sculpture was perfect as it was. This fact is not documented, but it is an anecdote that has been told over and over again. What is documented instead is Canova’s refusal to complete the Elgin marbles when they arrived in London: “I would never add a limb,” he said. Thorvaldsen instead intervened on the Aegina pediments in Munich: he completed every single figure, mostly wrongly, and now all his “restorations” have been taken off.

In contemporary archeology what we would normally do is to not intervene on the object itself; but if you want to make an attempt at reconstructing you make a plaster cast on which to experimentally add the missing parts.

CP: I am a great admirer of Thorvaldsen and I am somehow sad not to be able to see his “wrongs.” But then again, I am grateful to Michelangelo that he didn’t touch the Belvedere Torso. It seems to me that the archeology of archeology is a unique filter which we can use to re-examine what we’ve ended up with as present and the future that has had to be postponed for it.