Minneapolis: the site of a deadly reckoning that recently primed the world for a new wave of civil rights activism. Within the microcosm of art, this frostbitten midwestern city pricks the ears of culture zealots for an additional reason, one that is not cataclysmic but nonetheless causes vibrations that can be felt on a global scale. The Walker Art Center is a cultural lodestar, whose perspicacious focus on performance art, new media, and publishing affirms its position as a critical touchstone for contemporary art.

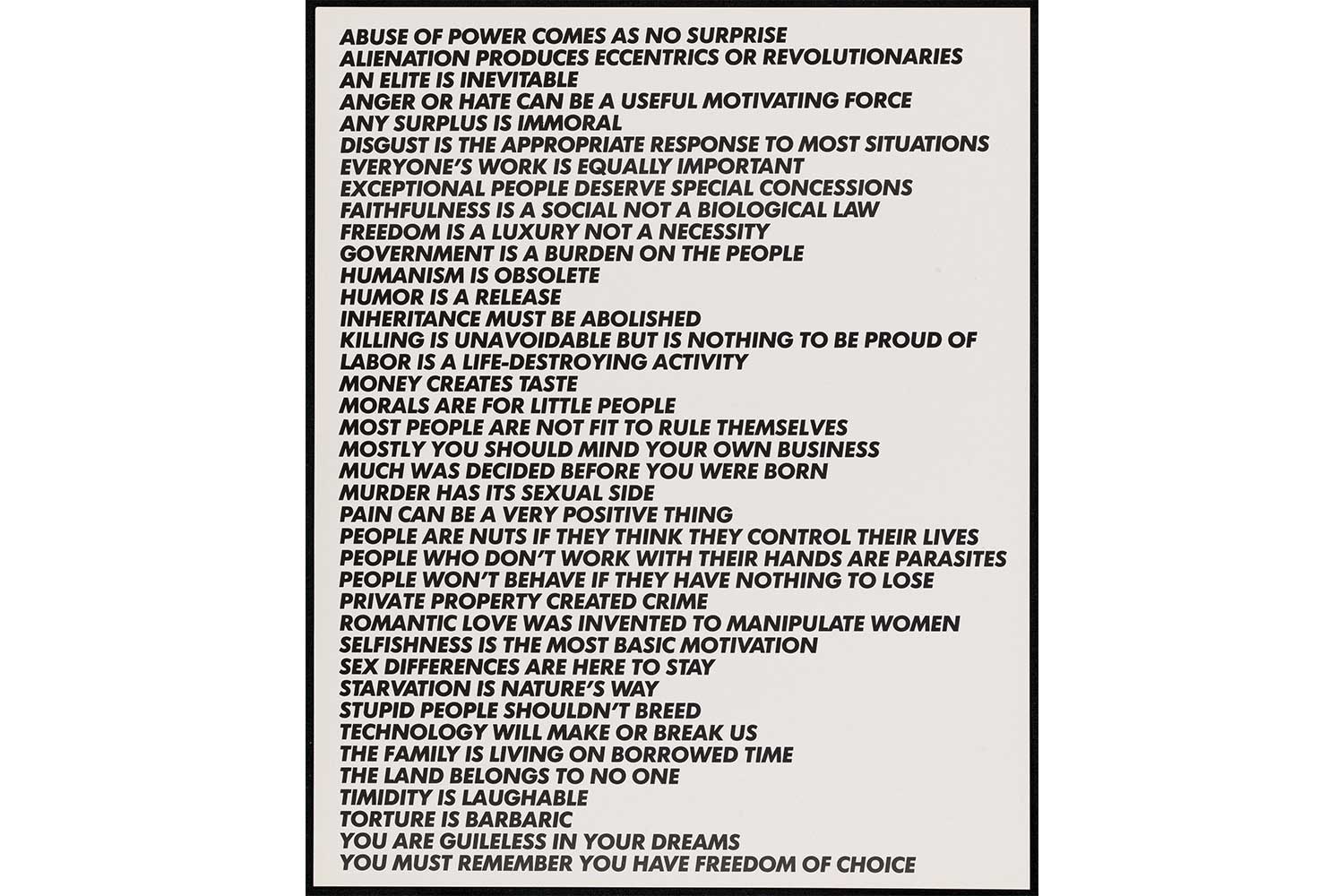

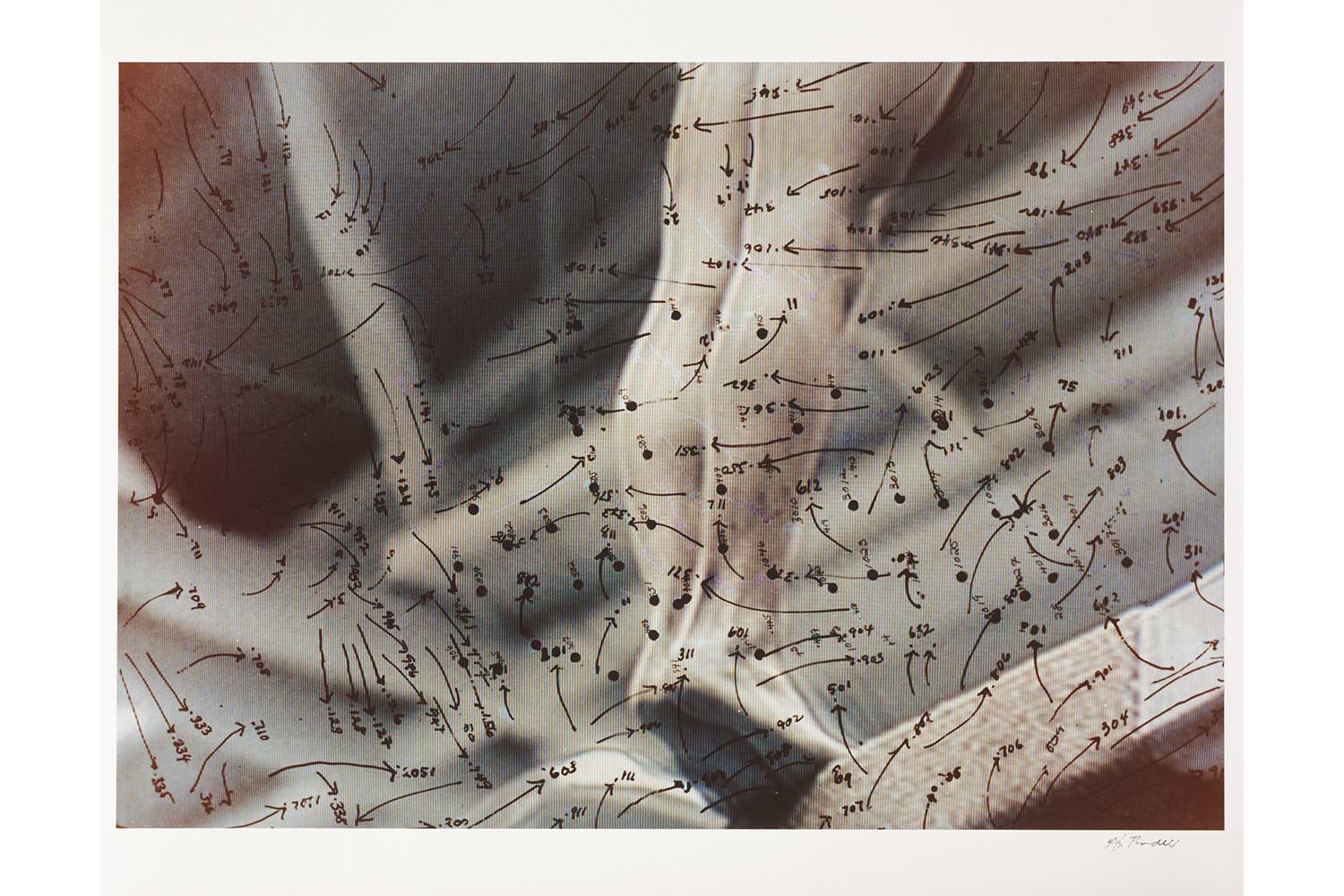

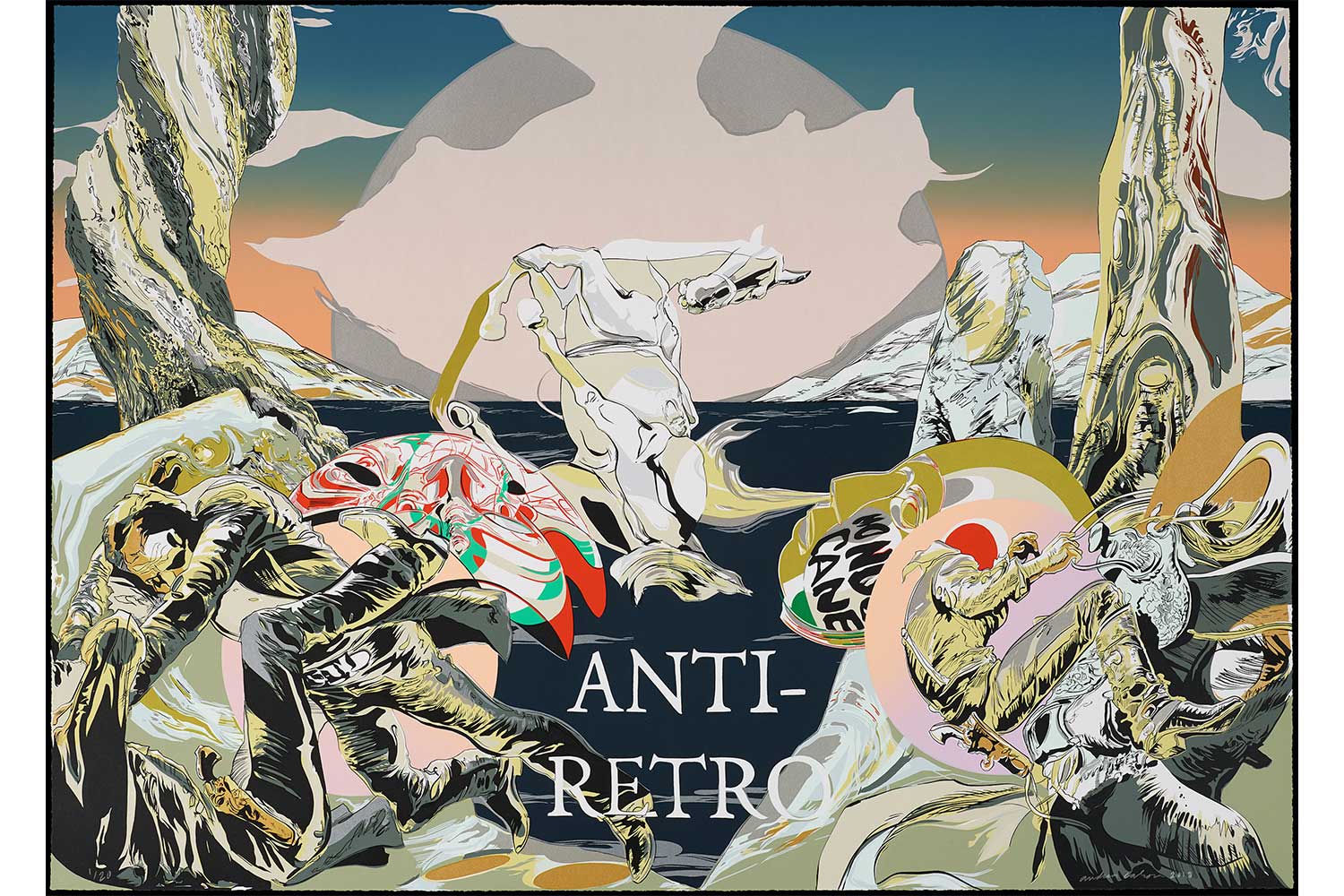

The Walker has chosen to navigate through the conflagration of this year in part by mounting a twelve-month exhibition titled “Don’t Let This Be Easy.” The show, which scales beyond the display of artworks with assiduous attention to educational programming and newly commissioned scholarship, showcases works by women artists in their permanent collection. This polymorphic exhibition of painting, collage, video, and ephemera surveys the creative output of anointed female artists such as Mary Beth Edelson, Shigeko Kubota, Ree Morton, Adrian Piper, and Howardena Pindell — all the focus of either posthumous or belated celebration. This presentation is juxtaposed with the practices of mid-career women artists who speak to the legacy of these postmodernists. The chosen descendants include Christina Quarles, Kaari Upson, and Andrea Carlson, whose permanence within the annals of twenty-first-century art is still under review.

As the title suggests, the thesis of the exhibition plays on the vital tenacity of women artists who navigated the doxa of misogyny in the mid-to-late twentieth century. These women endured the flagellations of being both a woman and an artist during a time when mother, wife, and art professional were seen as mutually exclusive roles. In viewing their work, our visual observation is weighted with the awareness of the societal conditions that played against each woman’s commitment to making art.

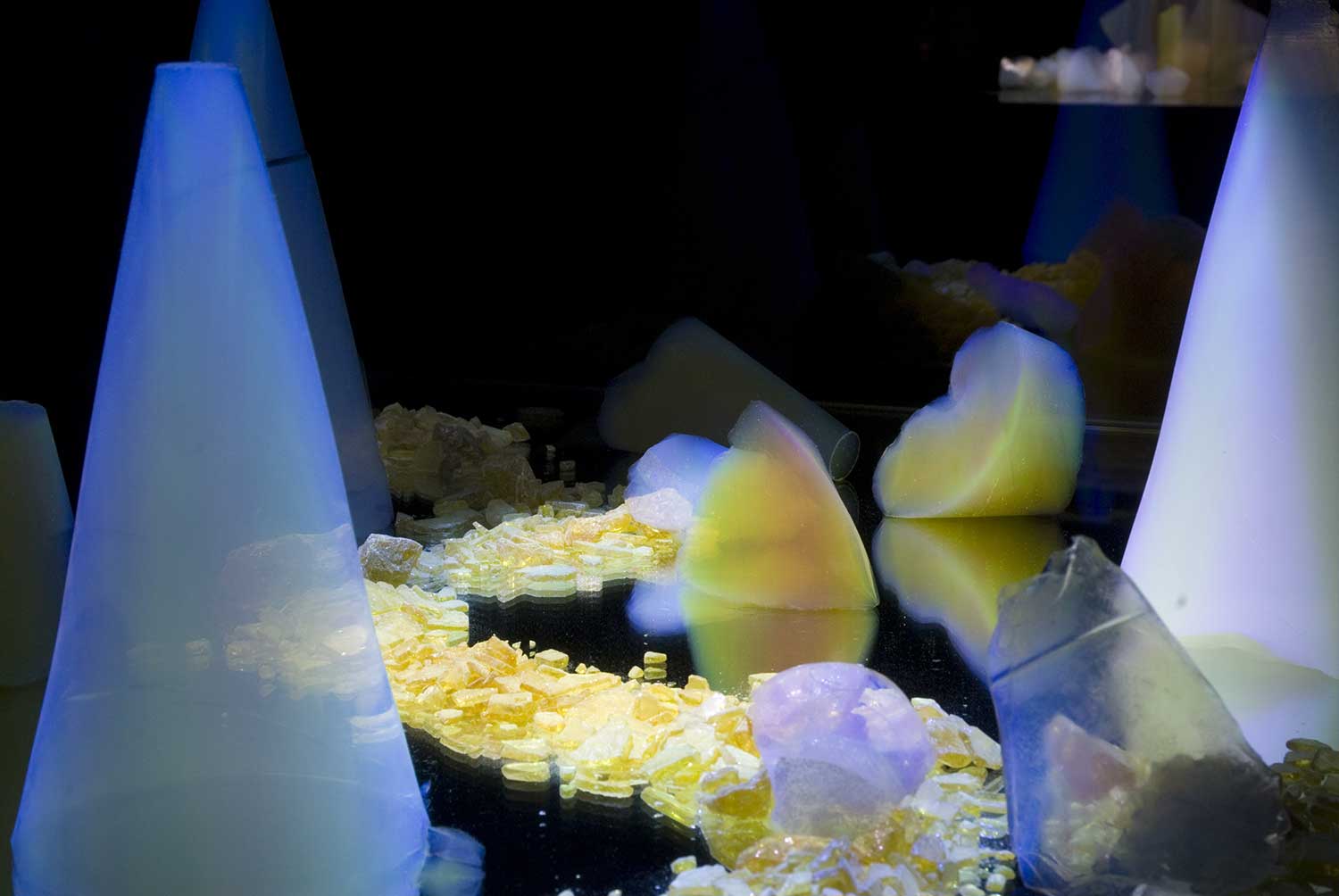

All the artists within the exhibition embrace their female subjectivity, some to the point of parody. For Ree Morton (whose luminous practice is currently being feted with a traveling US retrospective) the position of exile from patriarchal art circles led to the embrace of lowly materials and lyrical sentiments, typically associated with frivolity and women’s work. Poetry, textiles, aphorisms, glitter, doodles, watercolors, pastels, and decal stickers pulsate with the loaded implications of domesticity. These forms are solidified in Morton’s work through the transformative process of encasing them in Celastic — a polymer-based fabric that allows for the artist’s cascades of ribbons, flowers, and banners to exist in three-dimensional free fall. Exemplary works of Morton’s that were acquired by the Walker and displayed within “Don’t Let This Be Easy” include Terminal Clusters (1974), a waist-high moss-colored wooden sculpture in the shape of a horseshoe. Standing guard over the exhibition from a far corner, the wooden form is punctuated by naked light bulbs, whose levity is enforced by penumbral petals and pink dots encircling the bulbs. Spread across the axis of the horseshoe is a Celastic-rendered ceremonial sash that heralds the piece’s title. Terminal Clusters proclaims this gardening terminology with ironic bravado. As Morton reclaims and subverts the pejorative, effeminate notions of botanical nurturing, she alters these concepts with a radical charm that is exemplary of the way in which many female artists chose to combat professional animosity with whimsical solemnity.

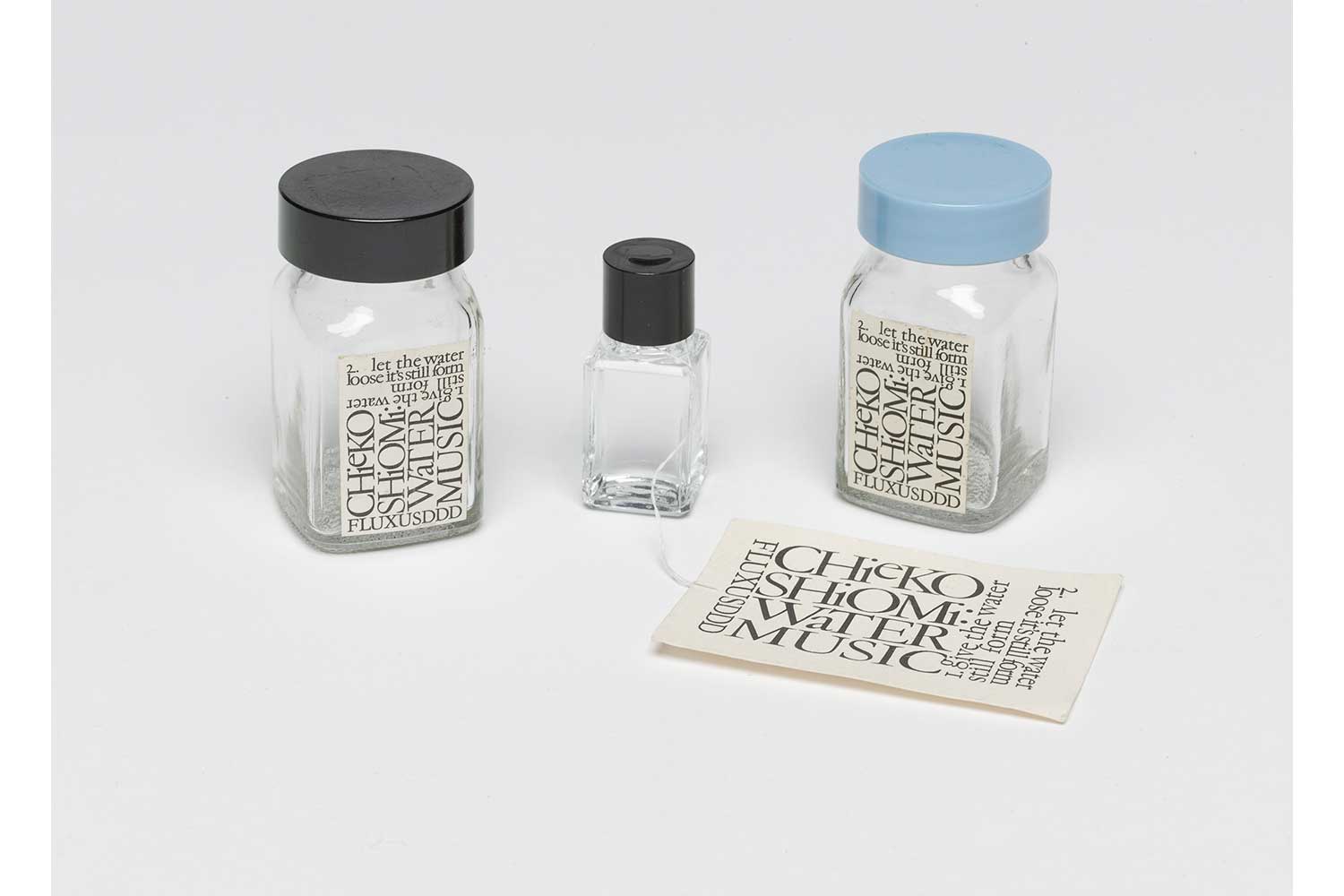

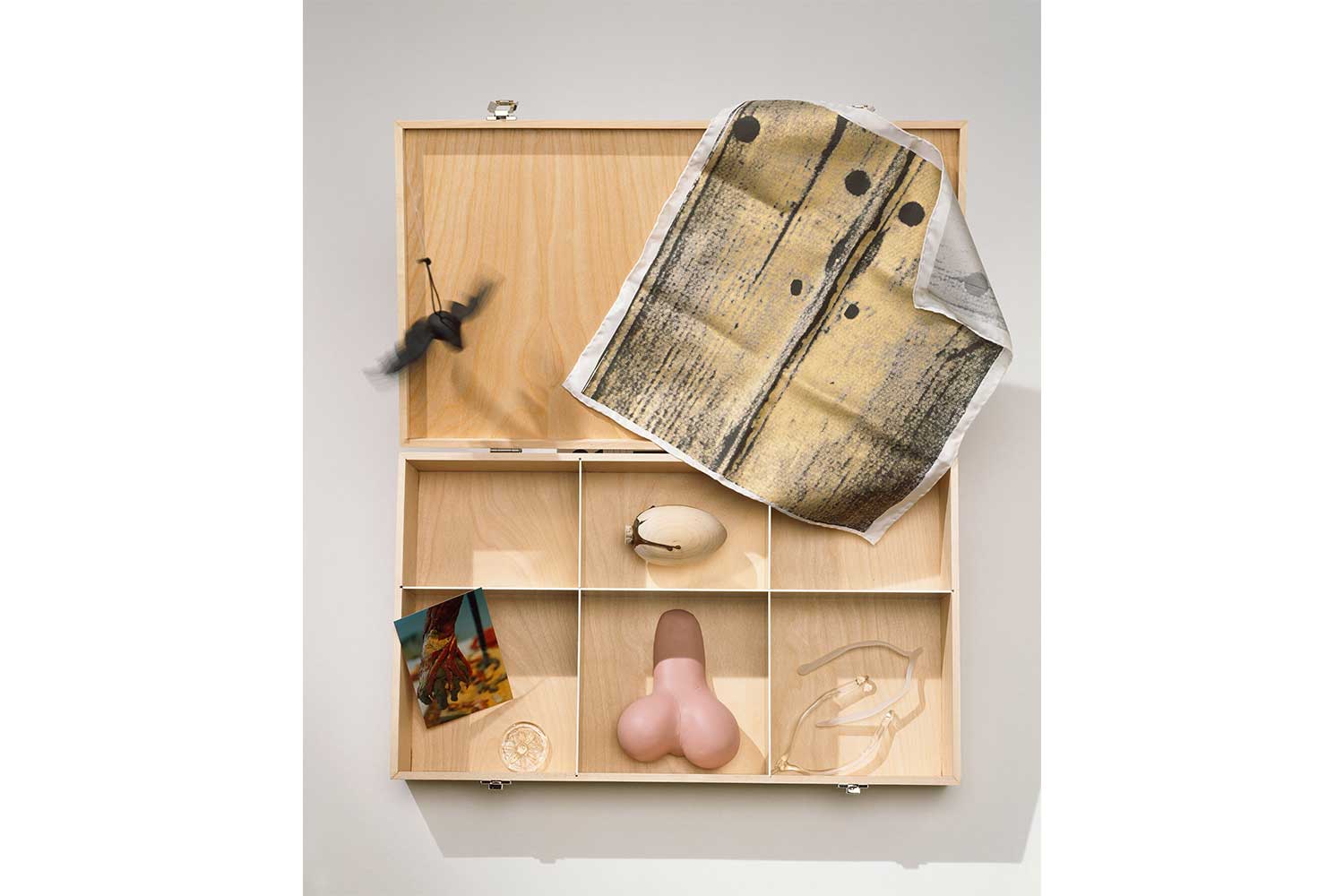

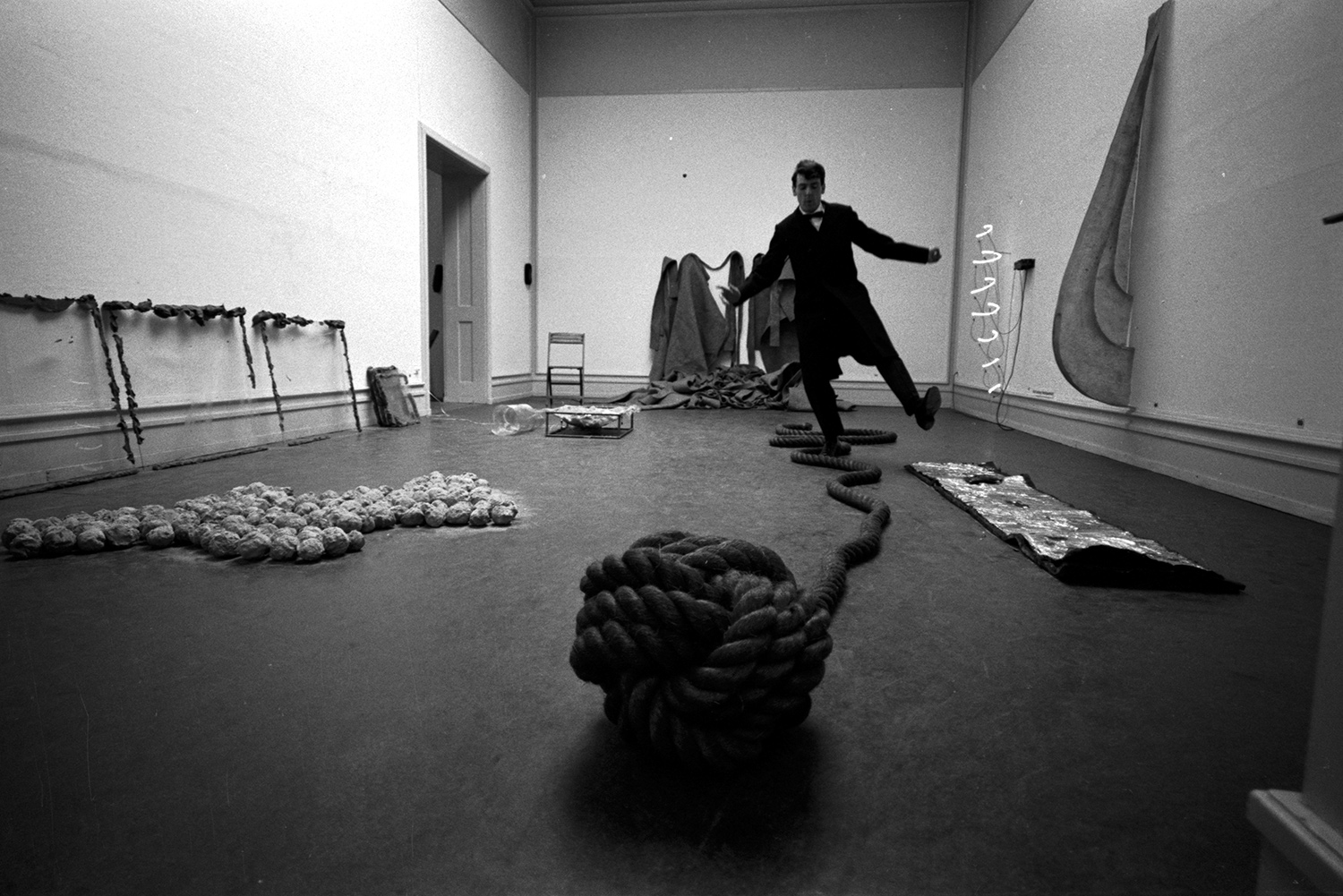

As a foil to the lighthearted sentiment and materially weighted forms of Morton, the exhibition includes video documentation, physical objects, and printed matter related to the actions of female Fluxus artists such as Yoko Ono, Alice Hutchins, Shigeko Kubota, Alison Knowles, Mieko Shiomi, and Carolee Schneemann. These women — who operated within the overarching narrative of a group — are cast within this show as part of a tacit sisterhood. Fluxus was unique within the history of the avant-garde for being a movement that featured an unprecedented contribution by women artists; not only was the female body central to Fluxus practices, but the group was a critical proponent of the women’s movement within the context of art. The curatorial decision to have a large portion of the exhibition devoted to the subgenre of Fluxus feminism is a provocative one, suggesting that the thrust of this show’s argument is to highlight how women artists operated in a man’s world. The counter to this is the inclusion of figures such as Morton and Eva Hesse, who reside in isolated margins around the swirlings of larger, male-dominated cooperatives.

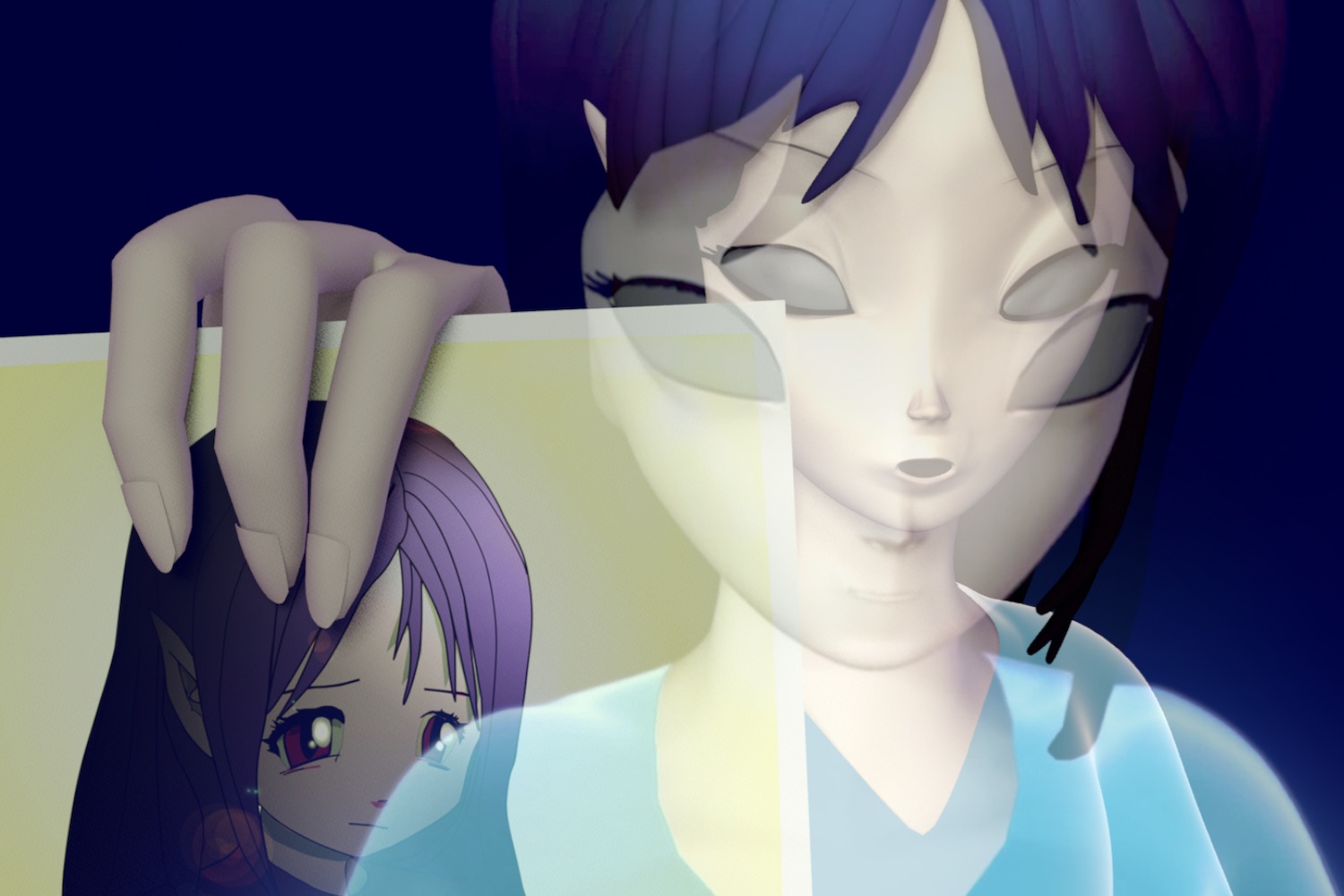

The choice of artist Kaari Upson as emblematic of the lineage of Morton and Hesse is apt. While her work lacks the saccharine quality that enriches Morton’s work, the adjacency of her material approach to that of her assumed predecessors is undeniable. Her work (J.O.) Dead Twin (2013), a lattice-etched mattress saturated in ethereal washes of blue and purple dyes, draws in the symbolic presence of the bedroom. With the implication of sex and the confined space of the home, it inexplicitly plays on the actions of the championed Fluxus females. With the lure of such recent works within this fomenting feminist art history, the exhibition teases out the potential for a new chronicle, one which will have to weave itself through the ambivalent arena of addressing gender politics, while celebrating these individuals as not just women artists but consummate figures whose contributions to art history exist beyond the realms of hership.