Opinions are like assholes. Or so it goes. London-based artist Dean Blunt gets this. His provocative exhibitions are designed to short sell the opinions they inevitably generate. In doing so they offer a complex spin on contemporary art’s current identity crush. Blunt’s not here to represent anything or anyone. Rather, it’s representation itself — via reading, interpretation, assumption — that his work problematizes.

Born in Hackney, East London, Blunt first came to prominence as a musician, one half of the wavy, sample-heavy duo Hype Williams. More recently, following album releases on Hippos in Tanks and Rough Trade, he’s gained critical acclaim as a solo recording artist. Less known — our subject here — are his exhibitions.

Blunt’s solo debut came in 2013. “Brixton 28s” at SPACE, London, was — in formal terms — a fairly conventional object show. A large, floodlit wall drawing misspelling the brand logo of a well-known Italian fashion house (“MOSCHION”) dominated the gallery. Other works included a mannequin dressed in a fake Marlboro leather sports jacket lying prone on the floor, a photo signed by rapper Asher D from early 2000s UK garage outfit So Solid Crew, and a short animation loop of an Evisu jeans–clad muscle man doing gym reps. Though recent exhibitions — at Cubitt, Arcadia Missa (both London) and Showroom MAMA, Rotterdam, for example — have tended to be tighter, more aphoristic, Blunt’s work retains the same basic structure from this debut. Emblems are drawn from black British, African American and inner-city culture and collided with the high-minded institutional complex of contemporary art, its audiences, discourses and expectations.

“New Paintings” (2014) was Blunt’s follow up show at SPACE. The exhibition comprised eight uniform, rectangular-shaped canvases stretched with Japanese selvedge denim and featuring — once again — the logo of denim brand Evisu (here hand-painted in a range of colors in the top-left corner of each canvas). These “paintings” were hung alone in SPACE’s standard, post-industrial white-cube main gallery. With no clarity offered, either by the exhibition’s po-faced title or the accompanying gallery text (which simply read: “The good die young. Ball in heaven.”), the exhibition was dismissed by some as a joke. And while the idea of denim paintings is burlesque, to stall there — as most interpretations did — was to fail to attribute sufficient gravity to the signifiers at play.

Writing in 2013 on the love affair between hip-hop and denim for Complex magazine, Sowmya Krishnamurthy points to the emergence of Evisu as the denim brand of choice for rappers in the early ’00s (being shouted out in tracks by the likes of Jay Z, Young Jeezy and T.I.). Labor-intensive to produce, made on narrow shuttle looms and finished with a hand-painted logo, Evisu jeans are an expensive luxury item that embodies the aspirational economy of hip-hop. It’s own reification complex.

For a much longer time painting has operated its own high-end desire-economy. Critic Jan Verwoert calls painting the “royal road” of art, a reflection of its sustained symbolic and monetary primacy over other mediums. Painting is a white, liberal zenith. High-frequency stuff, like opera, ballet or the novel. However, more recently, post-conceptual art has found in painting an excellent position from which to disavow historical reification, usually via medium-specific, cannibalistic gestures that are parodic or, at times, cynical in nature (think about Cologne artists championing bad painting, the way their art continues to haunt us today).

Blunt’s “New Paintings” seem to be in dialogue with each of these aspects. Miming their own superficial stupidity, intersecting fundamentally different regimes of elite cultural value while simultaneously signaling a fresh move in post-conceptual painting’s ongoing endgame: one in which blackness is introduced to the strategic palette.

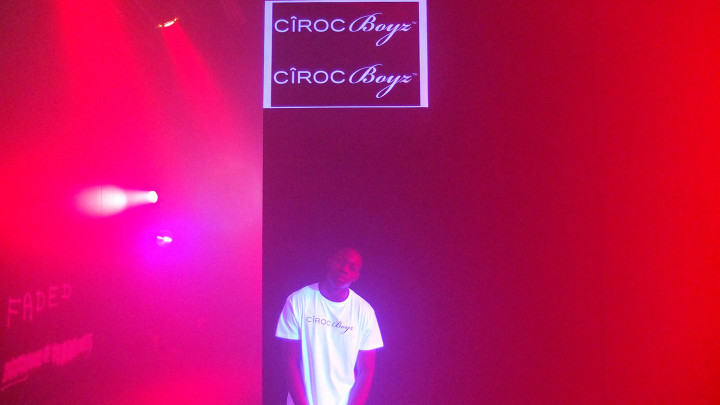

There’s no way of affirming such a reading, of course. In addition to never turning up at his openings, occasionally cancelling shows at short notice, and, well, just lying a lot, Blunt rarely gives interviews about his art and is never straight about its meaning publicly. By shutting up, Blunt diverts attention. Indeed, it’s us, the audience, who are often the real focus of his work. A fact never clearer than during “Urban” (2014) at London’s ICA. Blunt’s most controversial project to date saw him transform the black-box exhibition design of a recently closed Hito Steyerl retrospective into a one-night-only promo-style nightclub event. Tenebrous ultraviolet light picked out swoll black youth patrolling in white “CÎROC Boyz T-shirts” (Cîroc being a vodka brand long-associated with hip-hop). Also snared by the UV was graffiti adorning the walls. “THE TURN UP IS REAL” announced one scrawl. In the main auditorium — the site, just three days before, of Steyerl’s film Liquidity Inc. (2014) — Blunt played a DVD by black stand-up comedy superstar Kevin Hart. After an hour the venue reached capacity. This resulted in a tense stand off at the door. Some wanted out. Others were desperate to get in, no doubt full of FOMO: What great spectacle was being missed? Finally, after two disconcerting hours, Blunt appeared on stage. He performed an icy, static, twenty-minute set from his album Black Metal (2014), then departed. The night was over.

In a review of “Urban” in Art Monthly, critic and curator Morgan Quaintance wrote:

Rather than addressing the vexed condition of cultural essentialisms foisted on black artists, the presentation of stereotypical aspects of black British and African American popular culture operated on the audience instead. Almost entirely composed of white, middle-class creatives not born in London, Blunt’s “black”-oriented content emphasized and exaggerated the audience’s racial and socio-cultural homogeneity. It instrumentalized and pushed attendees into the awkward performance of a parasitical public: a community of modern negrophiles indulging ironically in authentic and transgressive black experience.

For Quaintance, “Urban” ensnared its audience — for a time, literally — in an environment in which their attendance was brought into a state of autocritique. Operating as puppet master, Blunt used a fairly innocuous pretense — a party — to again concatenate signifiers. Symbols of an essentialized black culture — Cîroc vodka, muscular black bodies, hip-hop and Kevin Hart — were used to snag a racially and socio-culturally homogenous audience on the barb of their own ethnic voyeurism. Those more familiar with Blunt’s work exchanged nervous “in on the joke” assurances with each other (but what joke?).Others — those more expectant of a straight-up party — were confused, angry even. A piss take? Performance art? Nervously self-aware, the audience was compelled to fix an intention to “Urban” — by way of valorization or dismissal. In a rare 2015 interview with I.D. Magazine, Blunt proposed: “Whether or not I had an intention is besides the point […]. I’ve been more amused by the shit that comes out of people’s mouths when they haven’t been guided […]. British people hate feeling like the have egg on their faces.”

Later in the same interview the art world is described by Blunt as “just another sandpit to play in.” In light of the social fallout his work generates, I’d argue that it’s actually the perfect play zone for him. Why? Simple: values mostly go untested in contemporary art. Blunt appears to be an artist willing to assay this, to forge situations over which audiences stutter. In doing so, his work engenders a public context for the autopoetic revelation of what otherwise goes unnoticed in contemporary art, be it unchecked privilege, assumption of universal access or outright prejudice. By saying nothing, responsibility for reading the work is placed solely on the reader. We thus encounter Blunt not through the filter of his own intentions (information is forever absent), but instead through the chattering discourse that surrounds his art.

As we have already seen, this commonly manifests as dismissive confusion. However, Blunt also attracts those who wish to appoint him in some way or another (Dean Blunt: the authentic critical voice of x or y). Against this, I would argue that though he entices such readings, the social and institutional antagonism of his art is not critical or political in any conventional or sensible way. Blunt’s art is not a thesis. Nor is it activism. His hermeneutics are deeper and stranger than that. Blunt’s output is ultimately delirious, built around the hazy subversion of his own identity and agency. The “realness” many try to read into it is, therefore, pitched badly. In The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness (2012), Poet Kevin Young reflects that:

[…] from reality television to keeping it real, what we most desire is an experience beyond the phony or phoned in, beyond the mode of pretense that daily life insists upon. While admirable, this urge ignores the valences of black life — an insistence on nervousness over a constantly tested black reality denies the ways black folks have found their escape where they can, often as not in the imagination — not as mere distraction from oppression but as a derailing of it. The black imagination conducts its escape by way of underground railroads of meaning — a practice we could call the black art of escape.

This, I think, is the real value of Blunt’s art: the way it escapes us and the standard critical structures we attempt to press upon it. Blunt not only gaps any analysis that would attribute an explicit teleological function to his work, he also semaphores the danger of assuming a shared discourse with him. Have you ever paused to question if the right to read and interpret all art through the same critical system might be a conceit born of a universality so often insisted upon — but denied by — those of privilege? As he plays tricks, shape-shifts, let’s you in, fucks you off — Blunt is asking us this timely question. In this way, his work has an oblique pedagogic efficacy. Blunt’s art of escape let’s us see for ourselves how most default approaches to reading, explaining or otherwise accessing art are locked into a specific cultural complex, one that is biased intellectually and blocked emotionally. This latter point is crucial. Amid the semantic dazzle and institutional defiance, there’s also a sincerely felt, almost erotic quest for Truth driving Blunt. Though about this the less said the better. (In silence there is feeling. And in feeling lies Truth. Restated: you need to STFU to get it. This— above all else — we learn from Dean Blunt).