For Dominique White, the sea is “a huge body, a living and breathing entity, that we don’t really understand.”1 We meet in the early days of January on Zoom. Myself in Zurich, Dominique in Marseille. When she stands up to fetch some books, which she then holds up to her computer’s camera for me to see, she vanishes into the blue, water-like background of the screen — into the sea. We discuss the importance of the sea in her work and the narratives and theories connected with it. We talk about the potential of shoals, the materials she uses, her role as an artist and caretaker (for her sculptures), and about longing for slow working (particularly these days). But I will begin with the sea. As I write, my thoughts return repeatedly to the book Undrowned by Alexis Pauline Gumbs,2 which accompanied me in the last days of the old year and is also a companion to Dominique White.

Dominique White’s artistic works, which have occupied me many times over the last few years here in Italy, are connected in myriad ways to the sea, to water — in the themes and theoretical reflections the artist deals with, in the materials and myths she draws on, and in the ideas and imaginaries she weaves. Many Afrofuturist narratives, definitions of Blackness, and envisionings of Black futures take place underwater and in metaphorical recourse to water.

Dominique White takes up this idea and expands on it, intentionally thinking outside of academic and Western knowledge constructs. “The Atlantic Ocean. The Mediterranean Sea. The Caribbean Sea. These bodies of water and others mark in significant ways what Black life is, and cannot be.”3 And so the sea, the ocean, is an eternal reminder of the transatlantic slave trade, of the Middle Passage, of the hold of the ships where Blackness was captured and contained. “Because what happened in the ship was precisely fantasies of flight,” says Fred Moten in Dreams are Colder than Death.5 Furthermore, the metaphor of the ocean functions not only as a space of transit and movement but also as a “complex seascape and ecology within Black diaspora studies that ruptures normative thought and European discourse.”5 A countercurrent way of thinking.

And the ship as a reference to slave ships or the rubber boat in the Mediterranean that runs aground off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa. Besides the sea and the notion of the ship as a container, Dominique White also attaches great importance to the concept of shoals as a site of Blackness, developed by Tiffany Lethabo King. Neither land nor water, the shoal is an offshore geological formation that can serve as a methodological concept to “disrupt the movement of modern thought, time, and space to enable something else to form, coalesce, and emerge” and thought of as a “mobile, always changing and shifting state of flux.”6 It is here, in these horizons of thought, that the artist situates her work and her demands for rebellious resistance and true liberation.

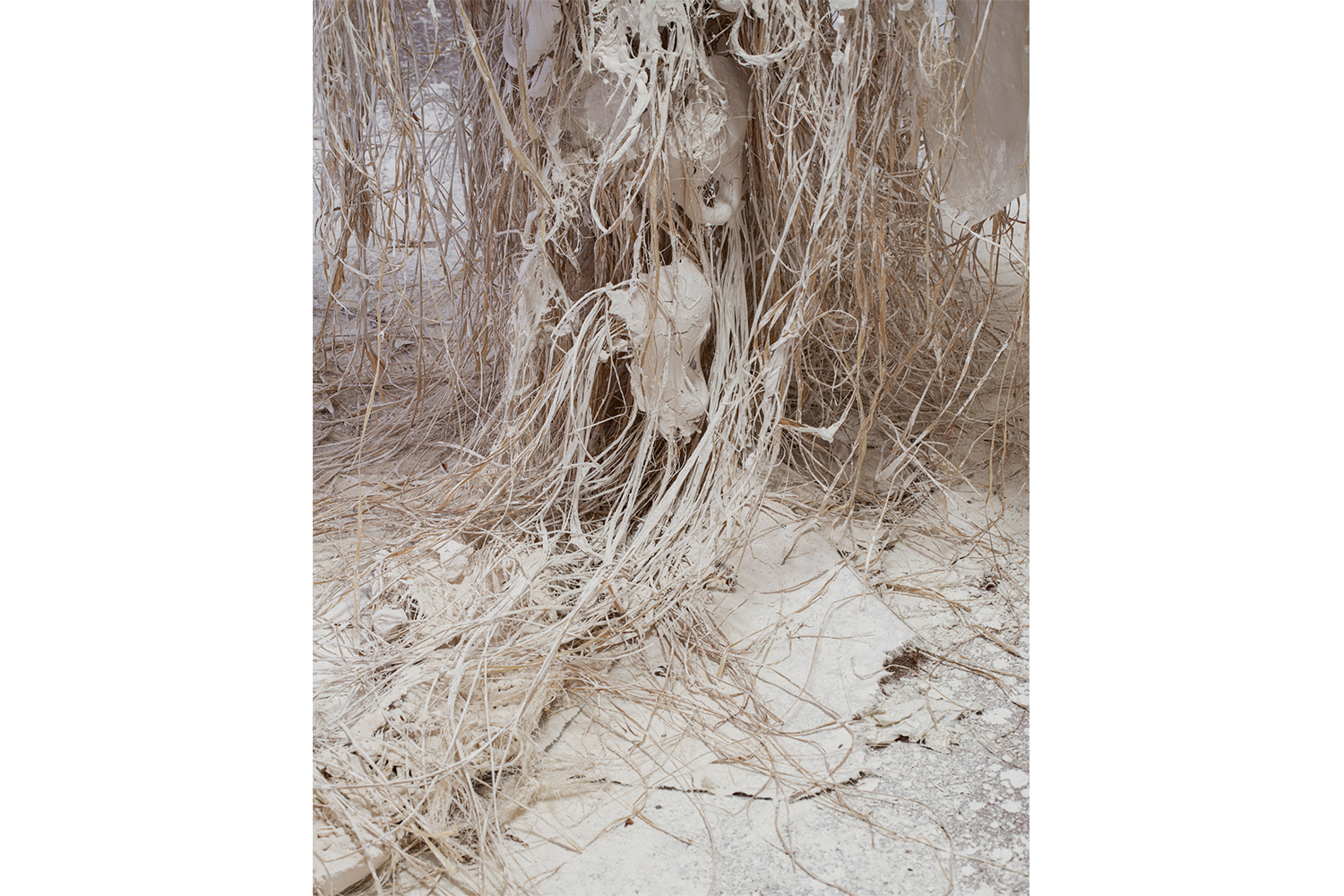

Dominique White’s sculptures Land, Nation-State, Empire (2022, installed at MAXXI L’Aquila (IT) last summer); The Hunted, the Betrayed, the Traded (2021); May you break free and outlive your enemy (2021); and A fugitive you cannot find a record for is the most successful fugitive of all (2021, presented at her recent solo exhibition at VEDA in Florence) are as powerful as they are fragile; I encounter them as suspended bodies. The fibers, some of them soaked in clay, seem to be holding their breath. Some appear as if risen from the water, and I wonder if they would swim or sink. They tell of emancipation, freedom, and escape, and I think of the words of Fred Moten.

The works’ titles are precise and remind me, for example, of the historical connections between the slave trade, the exploitation of the earth, and the racist dehumanization of people that took place in this context. (Total commodification. Slaves for gold.7) And of the flight of displaced persons, the attempts of Western nation-states to contain and prohibit the movement of Black people, and the links between people fleeing and the West’s past and present grip on the African continents. Can We Be Known Without Being Hunted (2022) — a hanging sculpture with relatively massive hoe-like elements formed of cast iron and a finely woven net of sisal and raffia — which Dominique White presented at Triangle Astérides in Marseille in 2022, makes me think of Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s comments on Hydrodamalis gigas: that the giant manatee was “discovered” in 1741 and became extinct only twenty-seven years later. “So she knows what we know. It is dangerous to be discovered.”8

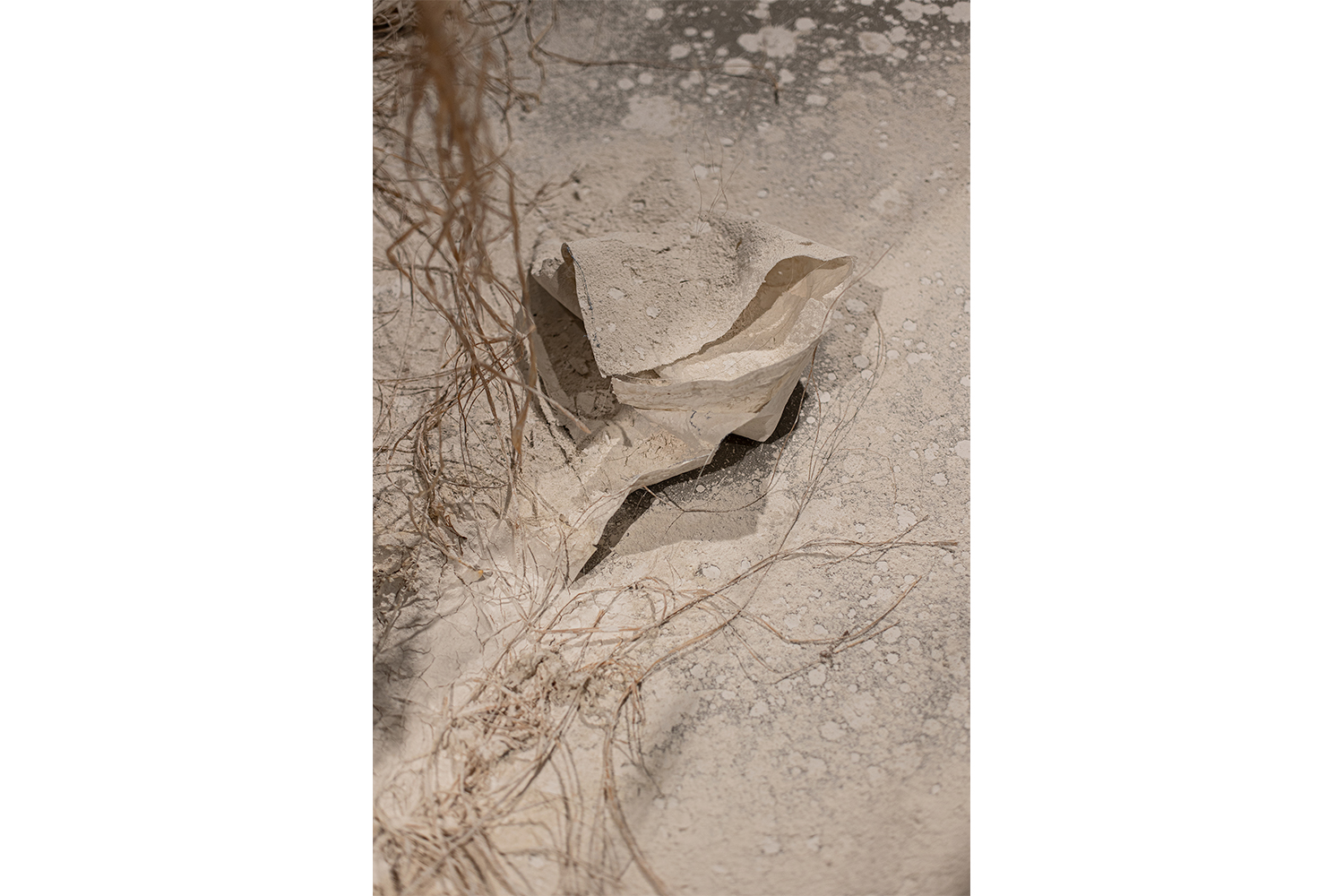

Dominique White creates her sculptures at her studio or elsewhere. In recent years, the artist has followed a rather nomadic (and strenuous!) mode of production, both enabled and necessitated by residency fellowships and exhibitions around the world. She uses old ship sails; fibers she carefully untangles from old, sometimes damaged and found ship ropes, raffia, or sisal; partially burnt and charred mahogany wood; kaolin clay; and untreated metal, which changes color and eventually oxidizes and disintegrates. This materiality determines the transient nature of the works: They are not static but can change at any time; they continue to breathe. Dominique White’s sculptural language interweaves moments of deconstruction and destruction into the act of creation. She pulls apart old ropes in order to weave new nets. One of her visual references, according to the artist, is the heaps of fishing nets along the coastline — damp or dried out, crusted with salt and sand. The sculptures emerge from physically intensive yet contemplative work. The various facets of her works are closely bound to Dominique White’s physical abilities. The limits of her body set the limits of the sculptures. In this sense, her body is part of the work. A dialogue emerges: Dominique White describes the sculptures as “entities and bodies, rather than works” and herself as a “caretaker” of these very bodies. The materials’ fragility and instability, the ephemeral conditions of the hanging elements, require special interaction and attentiveness. This is an aspect of artistic production that, for Dominique White, raises questions about the conservation and usability of her work. It is a reflection on withdrawing oneself from the process and the slow and gradual dissipation of some of the materials. On practicing a different pace of work and production. Working more mindfully, giving more time to things. Allowing the hands to rest, and to wash off the magnesium. Allowing thoughts to ferment. Moments of care, not definitive answers, are what interest Dominique White here, and cultivating an awareness of them.

In the studio, Dominique White is alone with her sculptures, with their materials and with magnesium on her hands — with music as a constant companion. Weaving the nets is a time- consuming, almost meditative, undertaking. It becomes an opportunity to step back from the action in order to move forward. With her noise-canceling headphones, she listens to Underground Resistance (a techno collective from Detroit), Mos Def, Drexciya, or Busta Rhymes. Afrofuturistic themes can also precisely be found in hip-hop, free jazz, and techno: “Daddy, what’s it gonna be like in the year 2000?” asks a child’s voice in Busta Rhyme’s intro to the track “There Is Only One Year Left.”

Dominique White explains that she starts her work by listening to music and reading theoretical texts, then continues it in her sketchbook. Music also serves as a bridge to more difficult-to- access theoretical literature. As the unraveled fibers are woven into new nets, their narratives and vocabulary emerge, which nourish Dominique White’s works and can be traced in them.

The image of the sea and shoals join the notion of hydrarchy — the ability for individuals to gain power over land by ruling through the instruments of water. In this context, Dominique White tells me, her work has evolved in the course of a very intensive process over the last few years. Before, her sculptures hung by delicate threads, somehow oscillating between escape and captivity. Today, especially since 2020, they are stronger, more destructive, and more rebellious. Hydrarchy from below, breaking with capitalist, imperialist structures. And the idea of the “Shipwreck(ed),” which Dominique White defines as a powerful movement that breaks the cycle of oppression. Finally, the sinking of the ship, signaling that Blackness can no longer be contained.

She writes to me in early January: “But if Blackness is eternally bound to the ship with no means of escape, the only logical route out is to become more demonic…to become more rebellious, more unquantifiable, to emerge in places that are impossible for Blackness to be, to be ungovernable, to be the antithesis of the categorization of Blackness itself.” For a new series of works, she hopes to research maritime archives in Italy for weapons, shipwreck debris, and other objects from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. She wants to discover what happens “if Blackness can no longer be contained.” Wading through the shoals.