Typically what cannot be seen

Is what we most like to see.

Longing is my favorite

Material for engaging (not picturing,

Not illustrating) holes.

— Pope.L, Hole Theory: Parts Four & Five

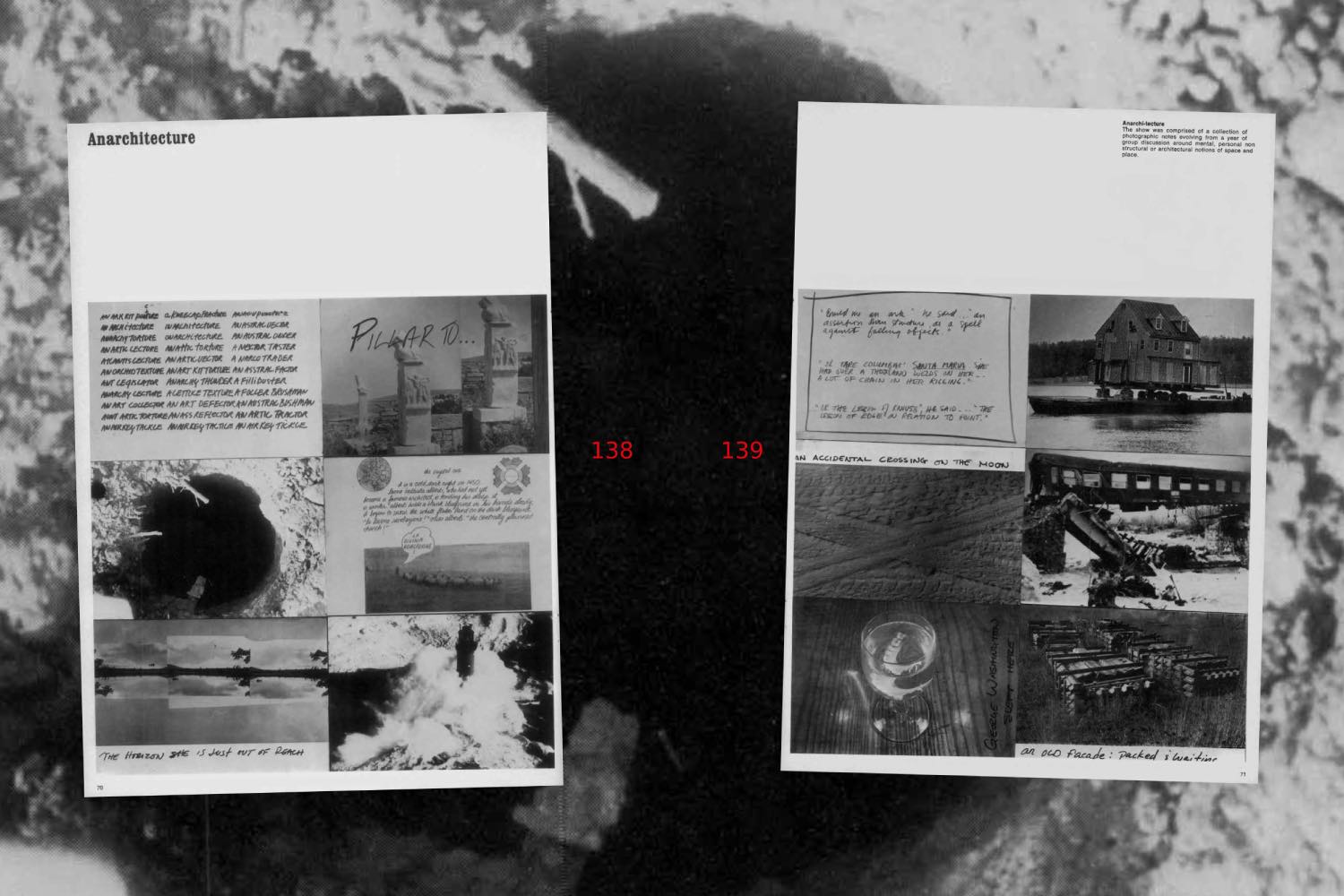

I first met David L. Johnson when he hosted an Open Session at Storefront for Art and Architecture, a recurring monthly series where an invited guest programs the gallery as a space for experimentation, collective learning, and shared dialogue. Storefront has chronicled the changing landscape of the built environment, both of New York City and beyond, for more than forty years. Acknowledging public space as contested — in cities, and in the public imagination — Storefront has historically presented exhibitions and programs that support the reclaiming of space, confronting systems of power and capital, and centering the political agency of artistic practice. For his Open Session, Johnson screened some of his earlier video works — One-Liner (2013), Snow, (2014), From the Street I Can See the Moon (2014), and The World (2017) — alongside C’est Vrai! (One Hour), a single-take film by photographer Robert Frank made in 1990 on the streets of SoHo and the Lower East Side. More than thirty years ago Johnson’s mother — a high school photography teacher and friend of Frank — helped cast some of her own students in some of the scenes. The film has greatly influenced the way Johnson employs handheld video in his own practice.

Watching these earlier videos and reflecting on Johnson’s sculptural works, I find myself turning to holes, voids, gaps –– all words that can be used to describe an absence of some kind. Pope.L writes: “I mean holes are occasions— / Opportunities which can take / Many forms, materials, and durations / (imagine a hole that has only duration).” Johnson’s work does not represent civic life; instead, it presents traces of the ways in which the structures that govern how one moves and performs in public space is marked by holes and voids and gaps, and then finds material ways to deconstruct and examine those absences. I would argue that Johnson’s principal medium or instrument is the performance of labor — either his own or documenting that of others — which is then rendered as an absent, invisible material in the final presentation of his work as it pertains to an art object or visual articulation.

Snow (2014) is a video work that oscillates between two scenes. One is of a maintenance worker shoveling snow off the New York sidewalk during a blizzard; the other is of the adjacent building at 51 Astor Place. Filmed from the outside through the building’s glass facade, inside the lobby we see real estate developer Edward Minskoff and contemporary artist Jeff Koons inaugurate Koon’s sculpture of a giant fourteen-foot-tall red balloon rabbit. Snow was originally displayed on a television set plugged into a utility outlet directly outside of the building’s entrance, thus making unauthorized use of the building’s electricity to power the piece and redirecting the notion of site-specificity. For what exactly is the site of this artwork’s subject? Sure, the video is filmed and presented “on-site,” yet like many of his sculptural works, the site of the subject is embedded within the political system — the “immaterial trajectories,”1 as Sarah Oppenheimer calls it, of our social choreography that the material of our built environment determines. In Snow, Johnson humorously peers into the absurd void of ever-increasing class dissonance. The maintenance worker is a threshold between the interior world of ostentatious corporate private equity and the raw public exterior, augmenting this divide and making these forces visible.

A similar absence of a prescribed site can be observed in The World (2017), a thirteen-second video that shows an NYPD officer peering through the window of a souvenir shop after hours, studying a map of the world with careful intimacy. The scene appears almost erotic, and Johnson’s handheld camera work captures a sense of voyeurism. Amid all the other objects in the shop’s storefront — the cards, the posters, the flags, the various trinkets and gift objects — the officer’s gaze is mesmerized by a map, an object whose making and reading is not only engaged with guiding knowledge, albeit subjective, but also sentiment. A map is an apparatus for representation that describes social constructions and inherent biases built into images that are then bestowed as truths. Pope.L’s words around longing as material resonate here in Johnson’s highlighting of the officer’s enamored state. The holes are in the information not visibly inscribed into the architectonics of our social registers. Writer Geelia Ronkina explains that the sidewalk on which the officer is standing to observe this map is what would be referred to in performance theory as “context venue, where the site-specificity of this space might evade the singularity given in the notion of an affixed site: this both could be, and is, many places; a moving everywhere into a somewhere; somewhere and everywhere.”2

In Warbler (2019), Johnson films a single take, at close proximity on ground level, of a small warbler sitting still on the sidewalk for thirty-six minutes, moments after it collided with the glass facade of a skyscraper in New York’s Hudson Yards. Hudson Yards is a massive rezoning and redevelopment site on Manhattan’s west side, epitomizing a luxury mega-project, which was partially financed by the gerrymandering of a map by New York State to qualify the neighborhood for funding meant for low-income areas.3 Johnson’s film has no sound, and eventually, around the twenty-eight minute mark, we see just the feet of anonymous passersby moving through the building’s revolving door. Breathing shallowly, the bird appears discombobulated and motionless, emphasizing the politics of glass as a mediating building material. Returning to Oppenheimer’s text in Movement Research Performance Journal, she writes that “buildings are time-based. Windows reflect daylight, doorways mediate procession, vents direct airflow. These forces modify the built environment in turn,”4 going on to explain how the movement, navigation, and performance of one’s body (be it human or nonhuman) in space is determined by this temporality. Steel and glass have seen its dominance and continued use across New York’s increasing vertical expansion and urban development. Here, the “hole” or the “lack” in terms of Pope.L’s schema is humankind’s antipathy (or lack of empathy) toward birds in metropolitan environments. As opposed to rodents and insects, birds occupy the most public places within cities; the only way they are able to feel the impact of increasing urbanization is not through intangible widening social gaps but through corporal intervention such as accidentally slamming themselves into the deceptive translucency of a glass facade.

Johnson thinks of the voids that affect other nonhuman entities in Kedi (2023). This intervention is part of a larger body of work titled CAT (2023–ongoing), and considers the half-million feral cats that live on the edges of New York’s industrial waterfronts, which have been undergoing rapid real estate speculation. Although originally installed in Berlin, Kedi is also without site-specificity — this could be, back to Ronkina’s words, “everywhere into a somewhere; somewhere and everywhere.”5 In this instance, Johnson observes the void as a physical absence — sites where DIY cat shelters made by activist communities have been inserted around city limits. Kedi consists of a series of mass-produced prefabricated shelters that can be distributed to any individual or organization committed to the care of these undomesticated animals and the stewardship of a new shelter. This work takes on critic Claire Bishop’s definition of participatory art as art by which “people constitute the central artistic medium and material, in the manner of theater and performance,”6 whereby Johnson is not only producing the art object but the situation (or holes as occasions7) in which the exercise is able to occur. The performance of shared labor here points toward a refusal of artistic production under capitalism.

In 2012, Johnson began 61 West St. (2018), a project documenting the destruction of a one-hundred-and-fifty-year-old wooden street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Greenpoint was historically once one of the largest sites of industrial production in the world. With the shift in infrastructure toward asphalt and concrete roads, and a financial incentive to rebrand the neighborhood as deindustrialized, Johnson collected more than four hundred fragments of wooden bricks over the course of three years. Though legally defined as theft, at the time creating physical holes by their absences, Johnson’s acts of removal produced an alternative condition of preservation in an effort to archive a moment in New York’s urban transformation. The fragments are exhibited in a procession, organized in order of state of decay. Presented alongside them are stolen work permits and a photograph depicting the reconstruction of the street in process.

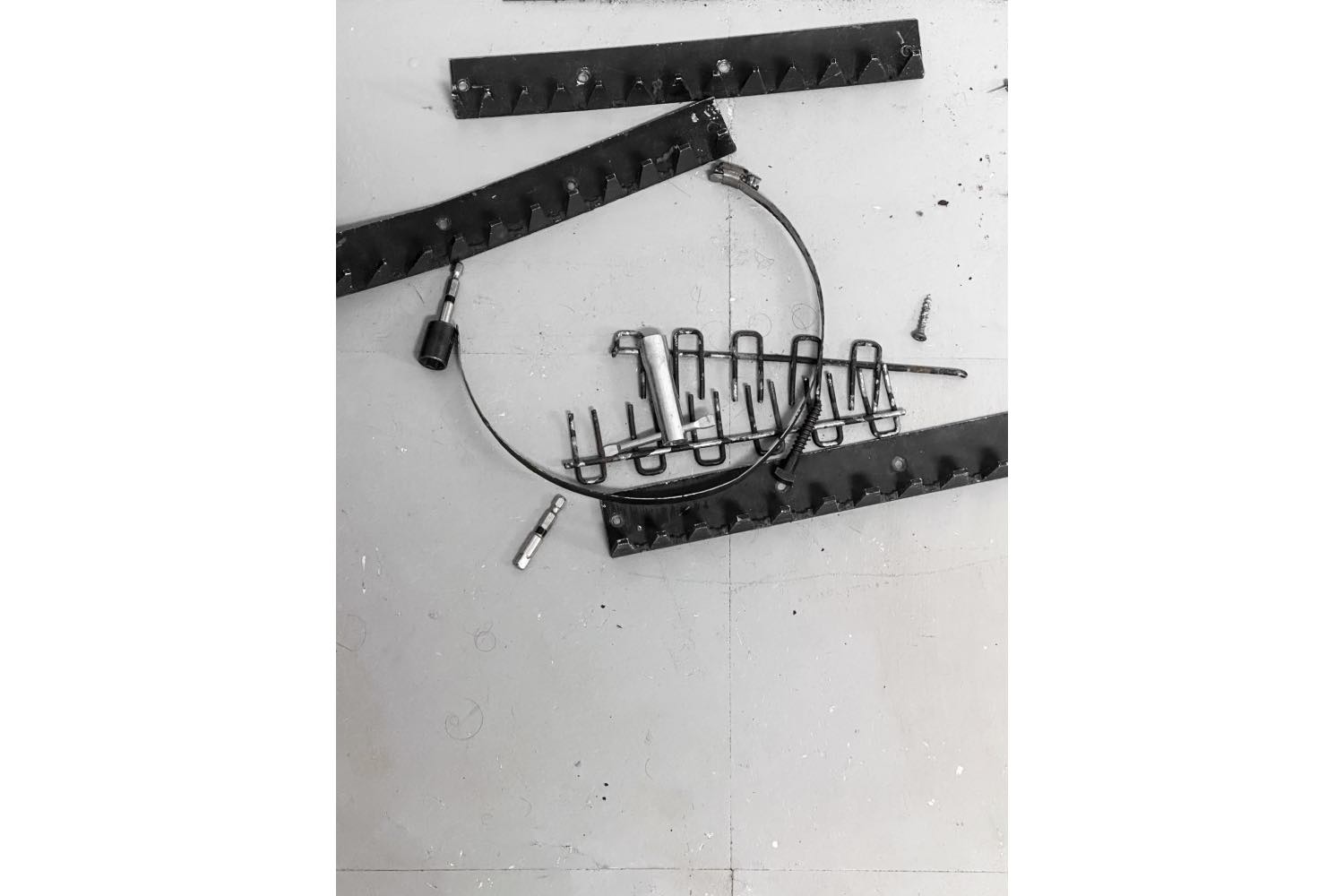

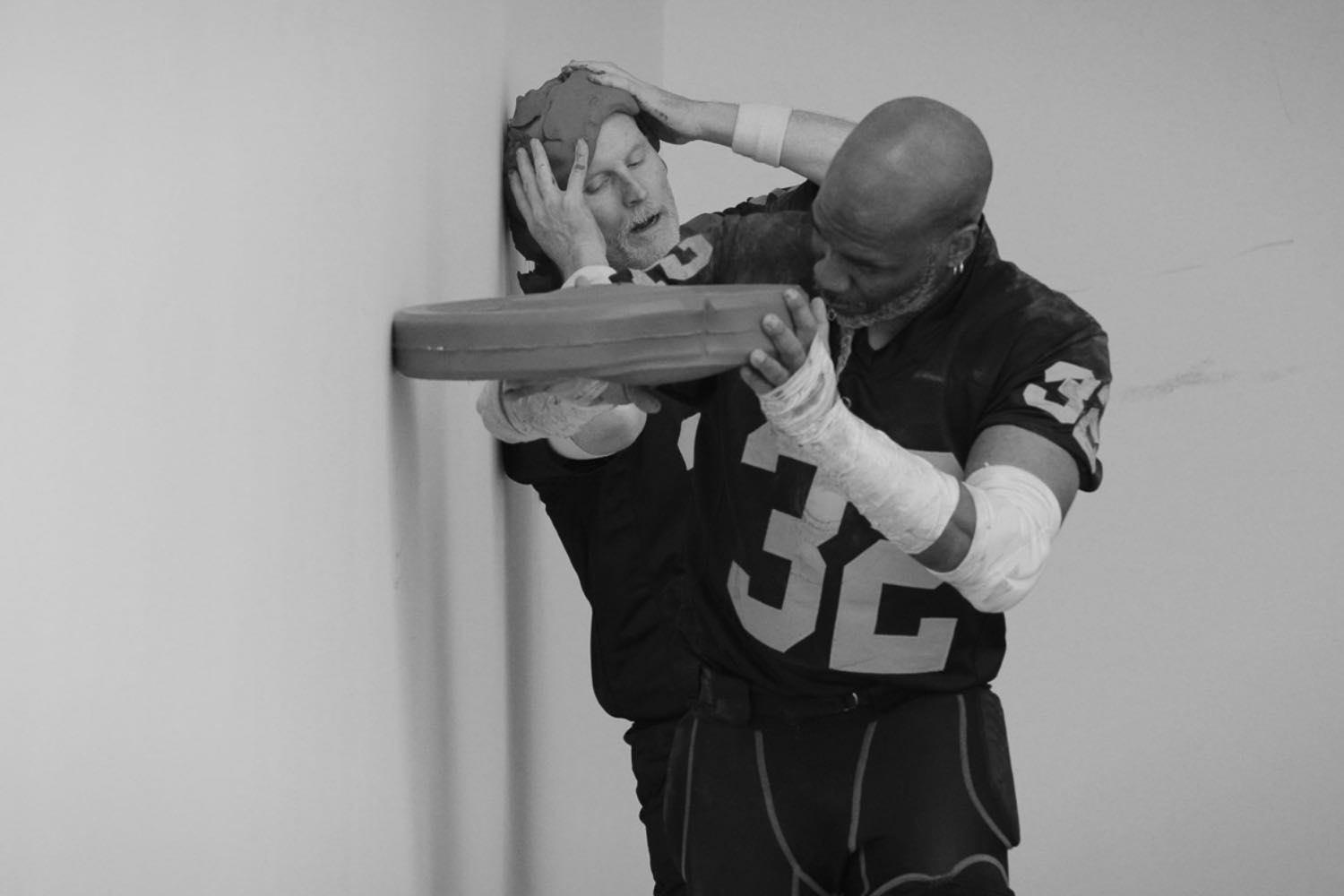

Theft as a performance of (unseen) labor is a recurring method or strategy throughout Johnson’s practice, and Johnson is perhaps best known for his urban interventions to various forms of hostile architecture. During the night, Johnson wanders around New York City, clandestinely “stealing” standpipe spikes, anti-homelessness spikes, Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) patrol tags, property plaques, street planters, and the like. These obstructions live throughout our cities and are enforced as modes of civic control, tools of surveillance, restrictions of behavior, and deterrents to public assembly. Once liberated, Johnson either displays these as sculptures or recontextualizes them as objects (such as in Adverse Possessions (2022-ongoing)) with new, more democratic functions (Community Garden (2023)). The sculptures become a residual result of the gesture, with the work being just as much about their removal as their procurement. In his ongoing series called “Loiter” (2020–ongoing), the subtraction of spikes installed over standpipes or attached to steps and benches, which prohibit people from using these as spontaneous surfaces to sit or lie down, open up the opportunity of loitering. Each removed object in the “Loiter” series bears a parenthetical name of the property’s owner from which the sculpture had been taken and decoupled from its urban elements (e.g., Loiter (Jeffrey), Loiter (Anthony), Loiter (Thomas)), a reminder of the ways in which increasing privatization of the city continuously impedes our spatial agency. The names are the only direct reference to a site, allowing them to exist as remnants of these holes, these voids, these gaps in the world. “Typically what cannot be seen / Is what we most like to see,”8 meaning their site is everywhere, invisible in their display, but visible through their absence.

Johnson and I are currently working on a commission to be presented next year in New York for a new Storefront initiative. Expanding on his investigation on the protocols of public space, this project, like all of Johnson’s works, can be positioned within the landscape of performance, both in metaphor and medium. This reading enables us to perceive not only the social performativity of the people who engage with the work, but also the works themselves as object-based activated live art, occurring in fugitivity within the built environment from which their void was either created or addressed. Holes are not static; they are in flux — some transient, some more concrete — but all puncture our socio-political fabric. Johnson locates these holes and beautifully reimagines their porosity.