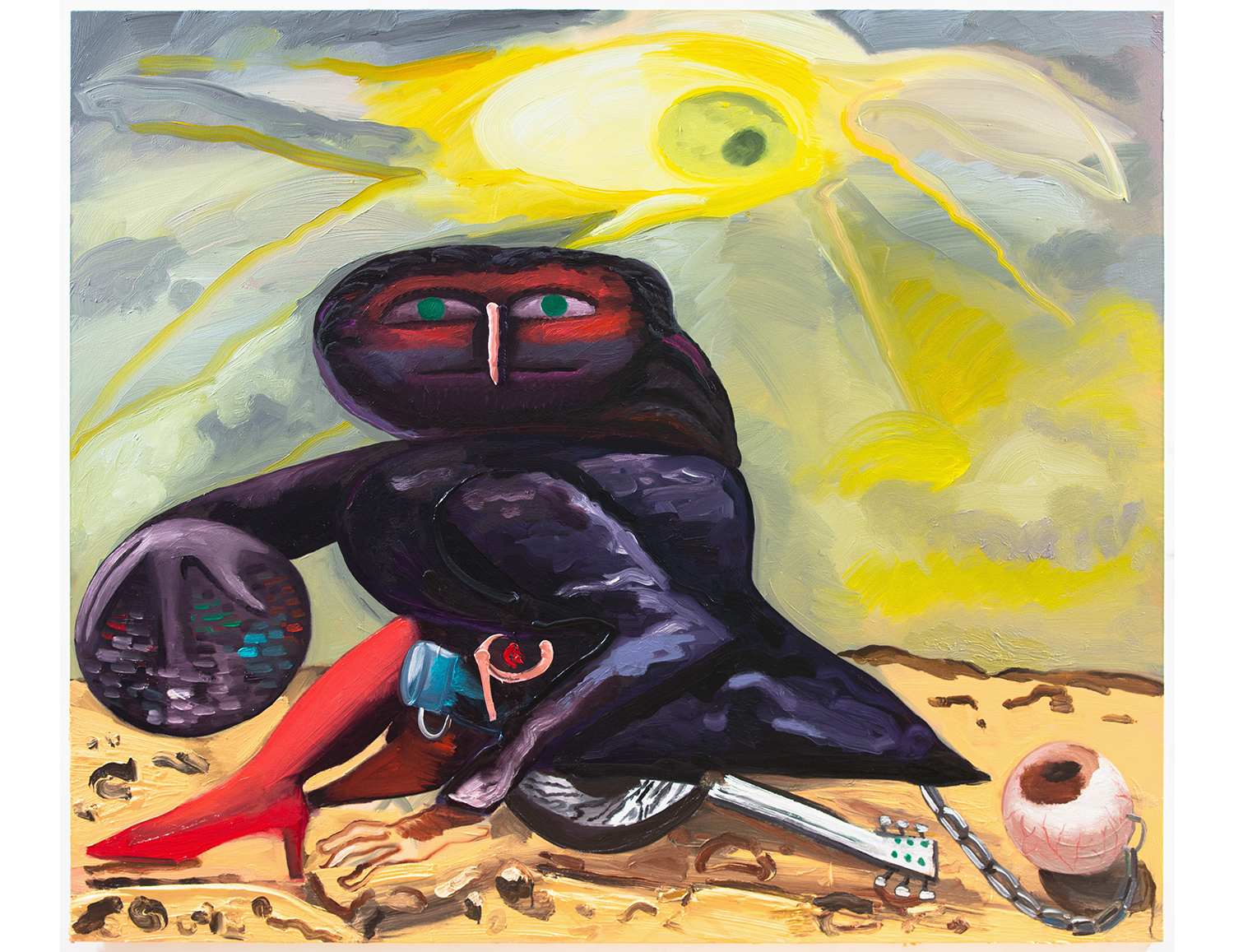

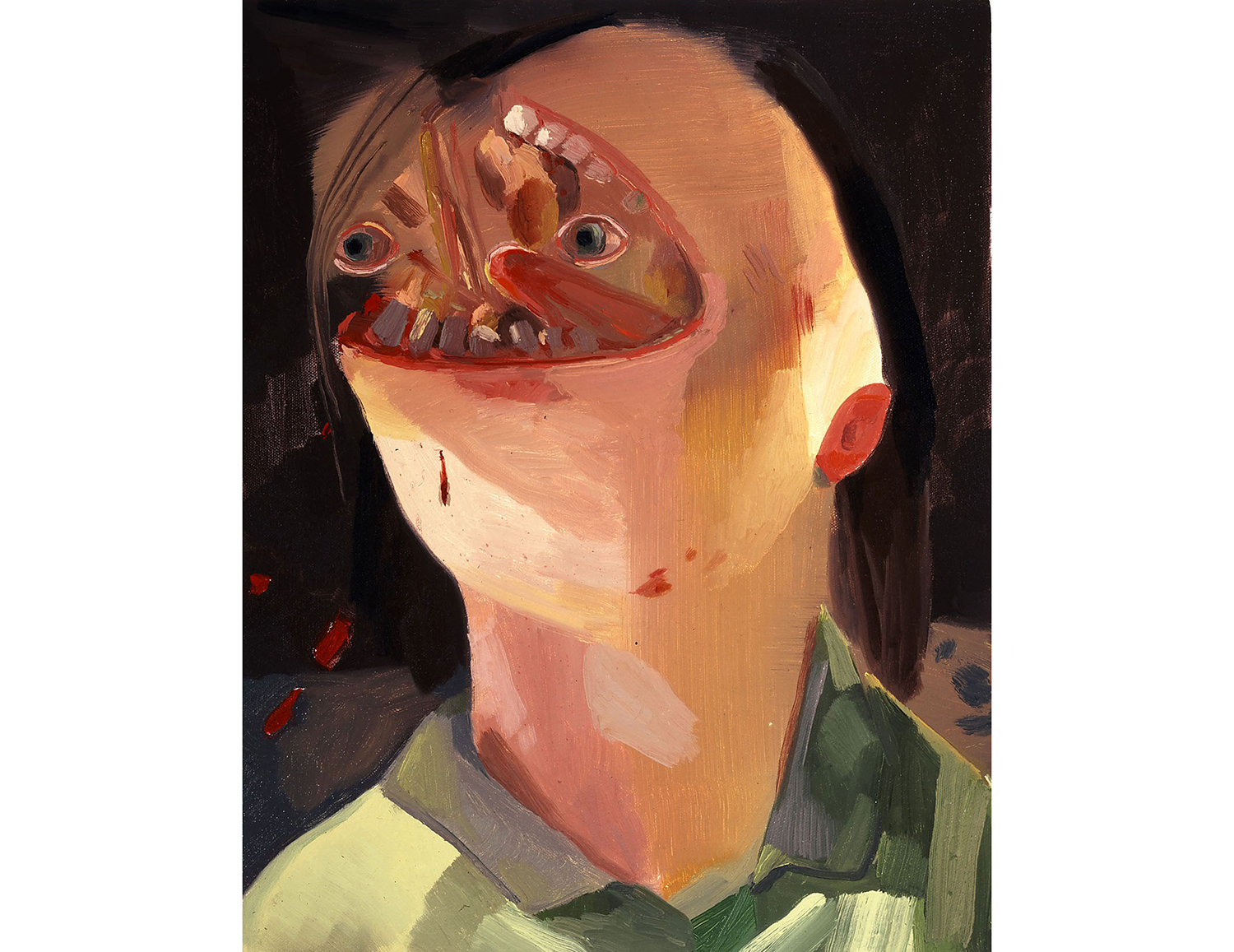

“How do you begin to depict a feeling?” wonders Dana Schutz, articulating a central problem that drives her artistic practice.1 For two decades, her work has brought impossible situations to life while striving to create a visual language for bodily sensations and subjective experience. Schutz’s paintings often seem to be a provocation of unbridled imagination, a “what if?” proposition taken to the most extreme and marvelously absurd conclusion. With bold, gestural brushstrokes and an almost sculptural layering of paint, Schutz produces vibrantly colored scenes packed with fantastical and cartoonish figures who self-cannibalize, transform, contort, and crumble apart. Through her subjects, she reveals the porous nature of the body, acknowledging it as an entity that leaks, excretes, reproduces, and consumes. When confronted with her paintings, it’s often difficult to decide whether to recoil or laugh. In an early series of paintings depicting sneezes as they feel rather than look, Schutz applies an eruption of frenetic brushwork that bursts from her subject’s piggish nose toward the edge of the canvas, effectively preserving this brief but explosive moment in time and space.

Another group of paintings imagine Frank, the last man on Earth, in various forms and postures, from a probosci’s monkey standing in a thicket of greenery to a rose-tinted nude reclining in a barren desert landscape. In these early examples and her many subsequent works, Schutz creates strange environments populated by figures whose extreme behaviors and grotesque physical conditions provide humor and entertainment while simultaneously inspiring discomfort and anxiety. Schutz has stated that she doesn’t intend for her works to hold a mirror up to contemporary culture, but rather hopes they will serve as affective spaces in which traditional hierarchies are reordered. Her maximalist compositions are a study of contrasts and an exercise in taking ideas to their limits. They reveal how the suggestion of narrative can often be more evocative and compelling than a straightforward representation.

For the past few years, however, Schutz has been most widely known for the intense controversy that surrounded the inclusion of her painting Open Casket in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Though its dramatic color palette and expressionistic style connect it aesthetically to many of Schutz’s other paintings, its gravely solemn subject matter make it an outlier in her oeuvre, which generally favors the outlandish and bizarre. The moderately sized canvas is a measured, abstract rendering of the black teenager Emmett Till lying in his coffin, his savagely mutilated face transmuted into a frenzy of brushstrokes and thick impasto.

Till’s brutal 1955 murder at the hands of two white men and the widely distributed photographs of his open-coffin funeral are considered crucial catalysts for the developing Civil Rights movement in the United States. The response to Schutz’s adoption of this deeply emotionally and politically charged subject was swift and impassioned. Artist Parker Bright protested the work by standing vigil in front of it wearing a T-shirt with “Black Death Spectacle” scrawled on the back, and engaged museum visitors in discussions about what he considered the painting’s failings. An open letter penned by artist Hannah Black and signed by several dozen art-world figures of color circulated shortly thereafter, and called for the work’s destruction. This altered the tenor of the conversation and sparked a heated debate about race, representation, appropriation, and censorship that, in New York Times critic Roberta Smith’s words, “split the art world.”2 The controversy even spilled into works of fiction, with the narrator in Olivia Laing’s Crudo describing her ambivalent reaction (in the third person): “She didn’t like or dislike the Emmett Till painting, she had strong feelings about what had been done to Emmett Till but as to what a person could or couldn’t paint, no.”3

While a number of artists and critics publicly took positions, many others were caught up in the ambiguities and complexities the case presented, unsure whether any clear answers could (or should) emerge. Some were indignant that Schutz compared her experience of motherhood to Mamie Till’s, with artist Aria Dean contending that universalizing the experience of black and white parenthood is “violent and nothing else.”4 Others, like Zadie Smith, expressed wariness about using racial binaries to determine who is and is not allowed to make work about black pain. Schutz herself admitted to feeling “uncertain” about the painting before and after the controversy, but denied any regret over creating the artwork, arguing that she found it “better to try to engage something extremely uncomfortable, maybe impossible, and fail, than to not respond at all.”5 Though ultimately no consensus was reached, the effect of the debate still reverberates several years later, both in Schutz’s newer works and in the art world at large.

It is tempting to read Schutz’s more recent paintings through the lens of the controversy and its aftermath, especially since the artist acknowledged that the public response to Open Casket has inevitably influenced her practice. However, the artworks she has produced since the Biennial also address a host of other concerns that have become increasingly urgent during a period of profound political and social unrest. A 2018 work, Strangers, seems to potentially allude to the Whitney controversy while reflecting more broadly on the unique challenges of living in an unstable and anxiety-ridden present. The painting features two ambiguously gendered, vaguely human characters standing in a desolate landscape under a cloudy, foreboding sky. Their contorted, entangled bodies are difficult to tell apart, and locked in physical contact, they almost appear a single, multi-limbed form. Schutz has suggested that they are adversaries brawling; however, the way that the upright figure holds its hunched-over counterpart could alternatively be interpreted as a gesture of comfort or protection. The pair stands atop a pile of jawbones, perhaps a metaphor for the conversation surrounding the Biennial controversy or a reference to the constant onslaught of intense and often vitriolic discourse that platforms like Twitter have facilitated. Both figures stare into the distance at something outside of the frame, which Schutz suggests may be their past or “a future that’s sort of confounding.”6 The canvas is characterized by the loose yet highly skilled handling of color for which Schutz is well known, and its reddish palette and bug-eyed, cartoonish characters have drawn comparisons to Philip Guston.

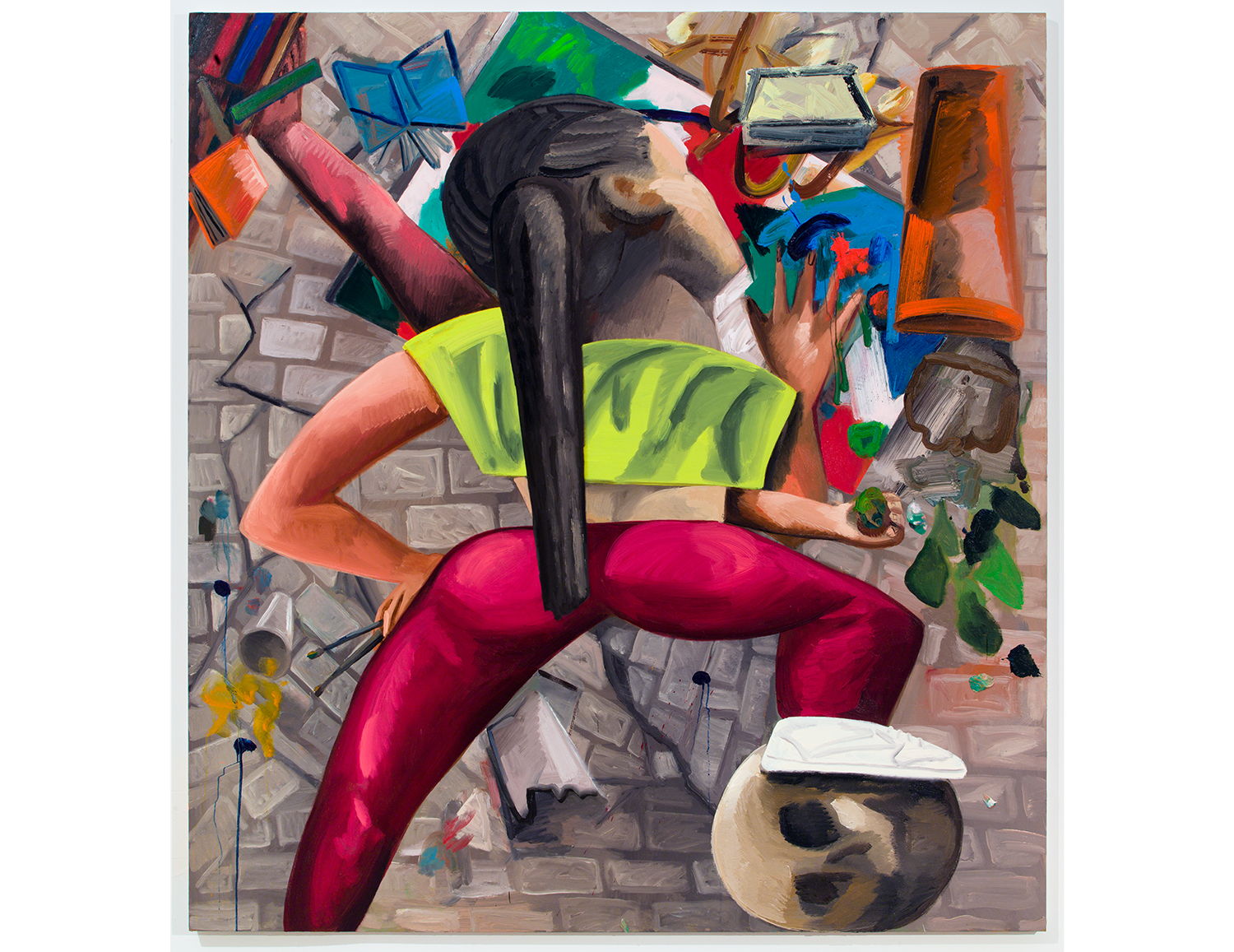

Painting in an Earthquake (2018) depicts anther scene of turmoil, with its many-armed subject continuing to paint as the walls literally crumble around her. Clad in burgundy pants and a bright greenish-yellow top, she rests her foot on a skull while simultaneously holding up her canvas and a shelf as books and cups topple down. Schutz was inspired by Richard Bosman’s Studio Series, which depicts various catastrophes befalling an artist in his workspace. With this painting, Schutz highlights the artist’s ability to persevere in the face of conflict and uncertainty, a subject that could represent Schutz’s own return to work post-Whitney or might speak more generally to the precarious experience of making art in an age of perennial crisis and volatility.

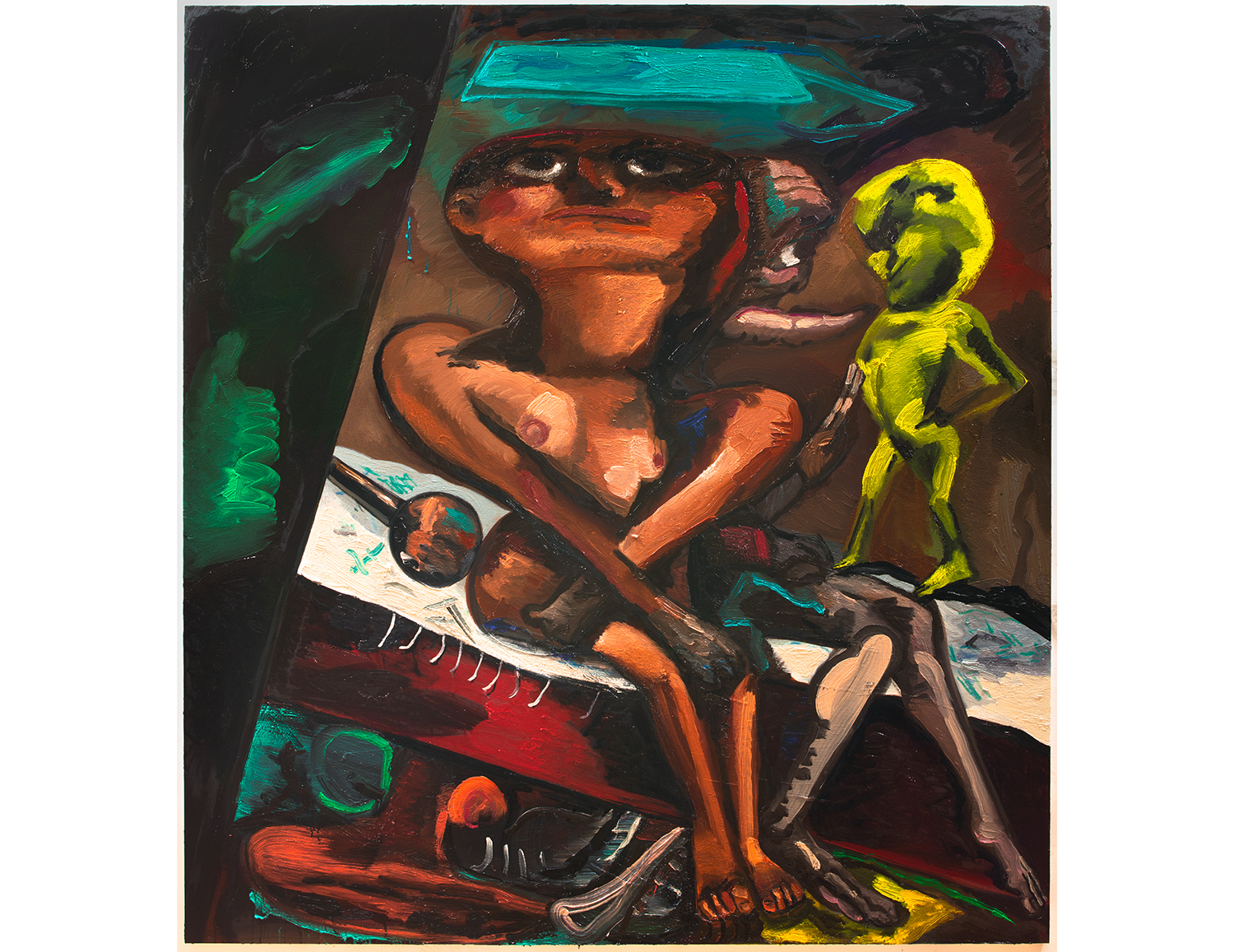

While Open Casket arguably revealed the limitations of Schutz’s practice, her painting Presenter (2018) is an impressive return to form that highlights the artist’s manifold talents. In this painting, a wide-eyed presenter stands spotlighted onstage with her underwear around her ankles as her gargantuan hand, which is nearly as large as the rest of her body, grasps at her face. Here, Schutz revisits her longstanding fascination with bodily contortion and disfigurement, which materialized so problematically in Open Casket but also ingeniously in, for example, Face Eater, a 2004 depiction of auto-cannibalization. Schutz has stated that she came up with the idea for the painting while listening to TED Talks as she worked in her studio. She began to wonder what would happen if one of the speakers completely derailed while stuck onstage, and how they might internally experience this loss of control and public humiliation. Thus when the presenter touches her face, panic transforms her hand into something overgrown and monstrous. Schutz reveals not only the terror of being held captive in the spotlight, scrutinized by an audience, but also the horror of being trapped inside one’s own body, unable to escape. Like many of Schutz’s other works, Presenter portrays a situation in which interior and exterior are impossible to fully differentiate. The painting exposes the uneasy division between “inside” and “out” as necessarily faulty — while we experience our lives internally, we are forced to present ourselves to the world externally. In this way, Schutz engages with some of the same ideas that inform Maria Lassnig’s concept of Körperbewusstseinsmalerei (“body awareness painting”), which calls for representing the body as it feels to inhabit rather than how it appears from the outside.

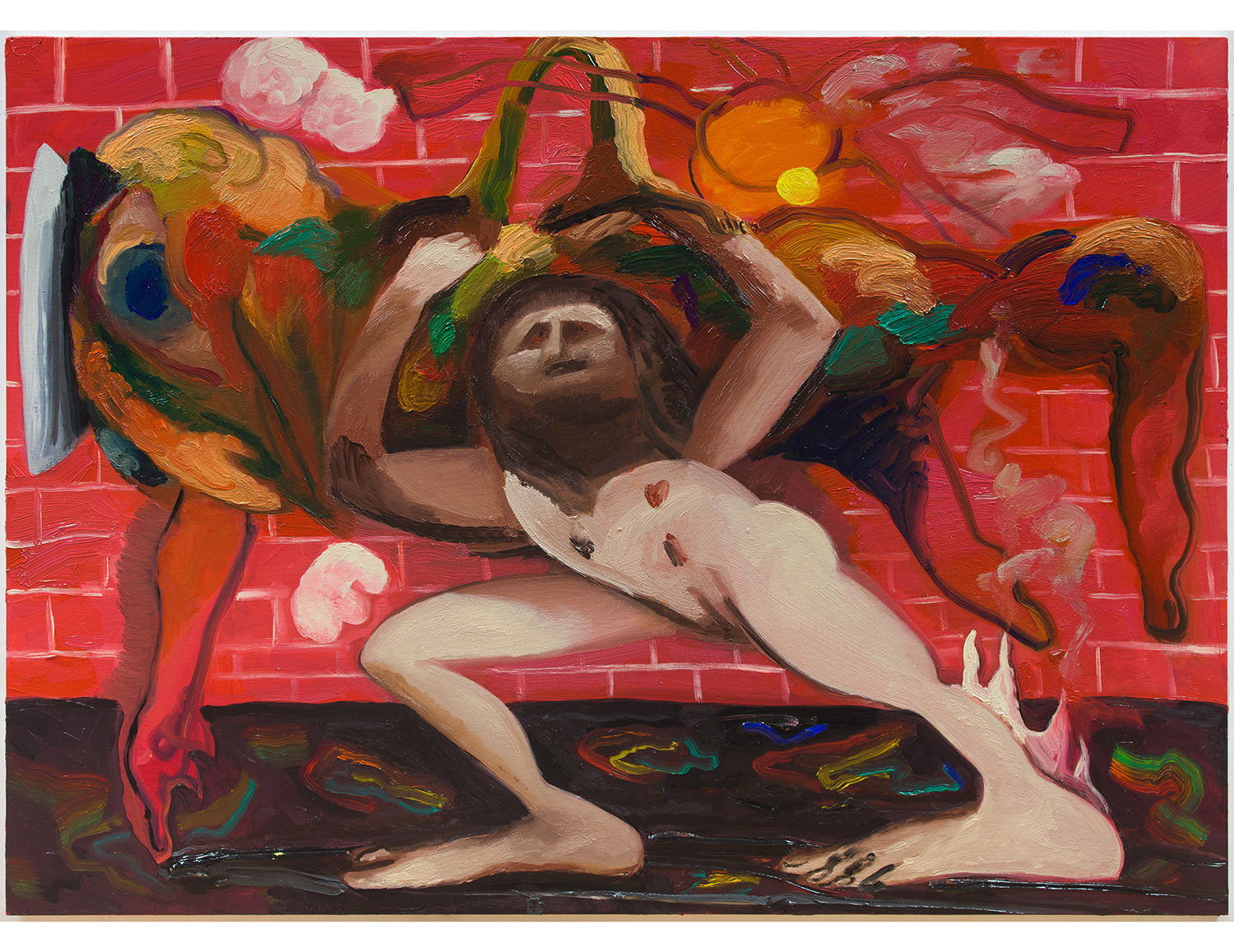

A 2018 painting, The Visible World, similarly features a figure in peril. The monumental canvas depicts a nude woman lying prone on a rock or piece of floating debris in the open ocean, a (wrecked?) ship visible in the distance. Her wide green eyes stare directly at the viewer, and with one hand she points down at the crashing waves while the other gestures toward a sea bird that has landed on her leg, an enormous raspberry in its beak. Daubs of vividly colored paint adorn the bird’s wing, transforming it into a palette, one of many references to the painterly process that appear in Schutz’s work. Here again she was inspired by art-historical precedents, and she specifically mentions Courbet’s Woman With a Parrot(1866) serving as inspiration for the piece. However, Schutz’s painting also calls to mind Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818–19) and even Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1503–15), which likewise presents humans in twisted poses interacting with animals and abnormally large pieces of fruit. The Visible World is rife with symbolism, and the work has been variously interpreted as referring to childbirth, artistic creation, biblical narratives, and classical mythology. As in her other works, chaos looms — in the murky waters scattered with debris as well as in the sky, in which patches of bright blue break through ominous reddish-gray clouds, suggesting perhaps a fire is raging somewhere in the distance.

A number of Schutz’s other recent paintings depict ocean scenes, including Imagine You and Me (2018), Boatman (2018), and Mid-Day (2019), which all portray figures in boats adrift on the water. The ocean can be calm and quiet, a space for reflection and renewal. But it can also be toxic and polluted with detritus, a mess of choppy waves, the epicenter of a brewing storm. For the subjects in Schutz’s paintings, the sea holds their vessels afloat, but also carries within its depths unforeseen hazards and turmoil. To be unmoored is to allow the water to carry you, knowing full well that it has the potential to wash you astray. Schutz’s work has always taken her to the limits of her imagination and understanding, and by all indications she continues to be guided by possibility as much as risk, in both balmy and tempestuous weather.