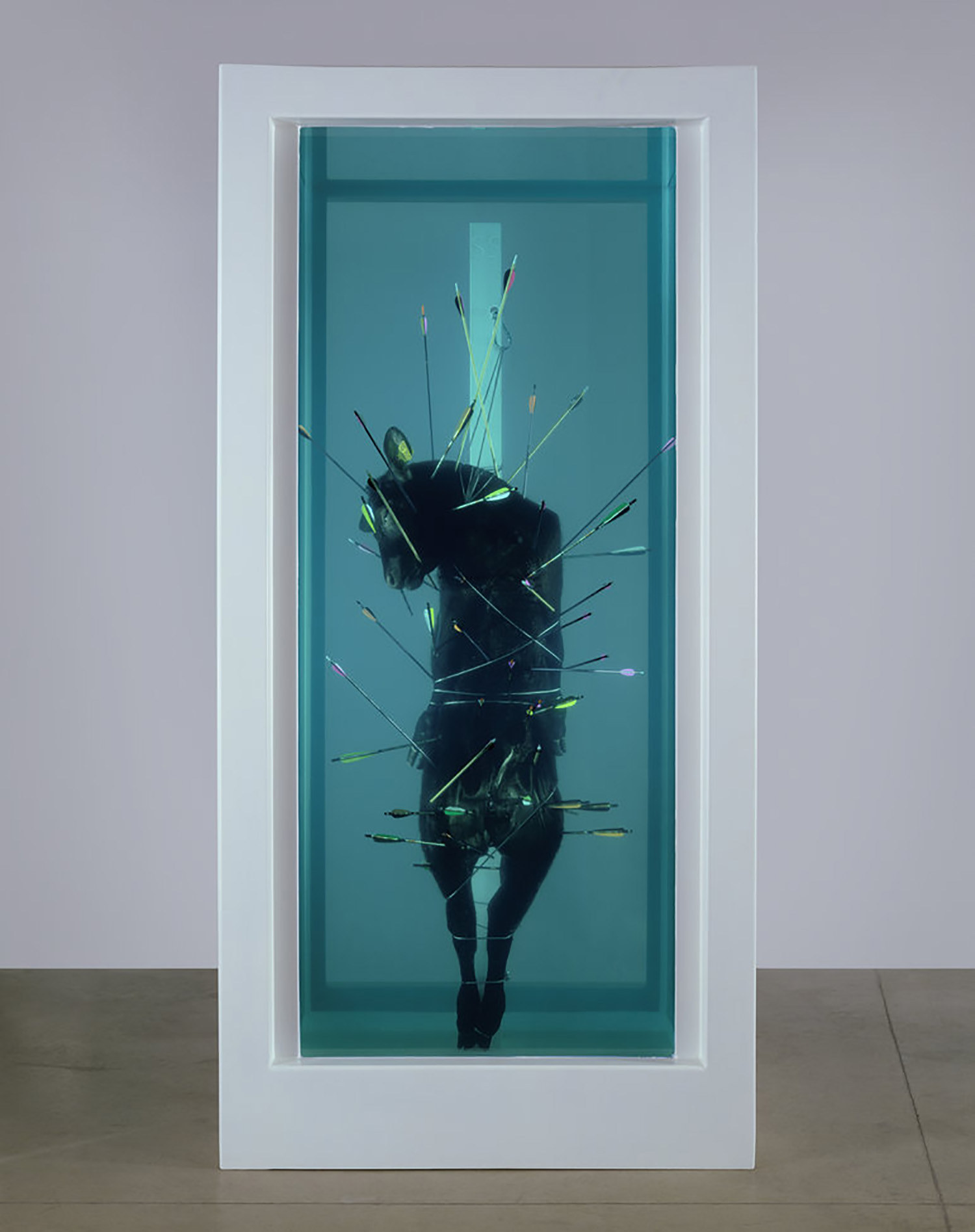

The series of T-shirts in the style of bootleg concert tees portraying artists such as Maurizio Cattelan or Damien Hirst, sold on the streets outside various art fairs and biennials in 2002 and 2003, was a project by Cyprien Gaillard (World Tour, with Payam Sharifi). It reflects two of his recurring approaches, working outside the studio and celebrating activities that often result from the transgression of legal or ethical rules.

Real Remnants of Fictive Wars (2002–04), a series of six 35 mm films, started with the theft of fire extinguishers. Gaillard invaded different landscapes with a thick white smoke, thus offering a remarkably personal revision of the notion of entropy defined by Robert Smithson — in fact, the last film shows the Spiral Jetty enveloped with smoke. Between land art and plain vandalism, the artist seeks to redesign the landscape by erasing it. The smoke inflicts violence on nature but simultaneously reveals and reinforces its beauty.

In Belief in the Age of Disbelief (2005), a series of engravings representing 17th-century Dutch landscapes, the bucolic sceneries become the grounds in which the artist introduces postwar tower blocks. For Gaillard, architecture has more to do with time than space; tower blocks are to him what Roman ruins were to artists centuries ago. While most of us consider them as monstrous scars disfiguring the city, he sees in them numerous signs of dynamism and potential.

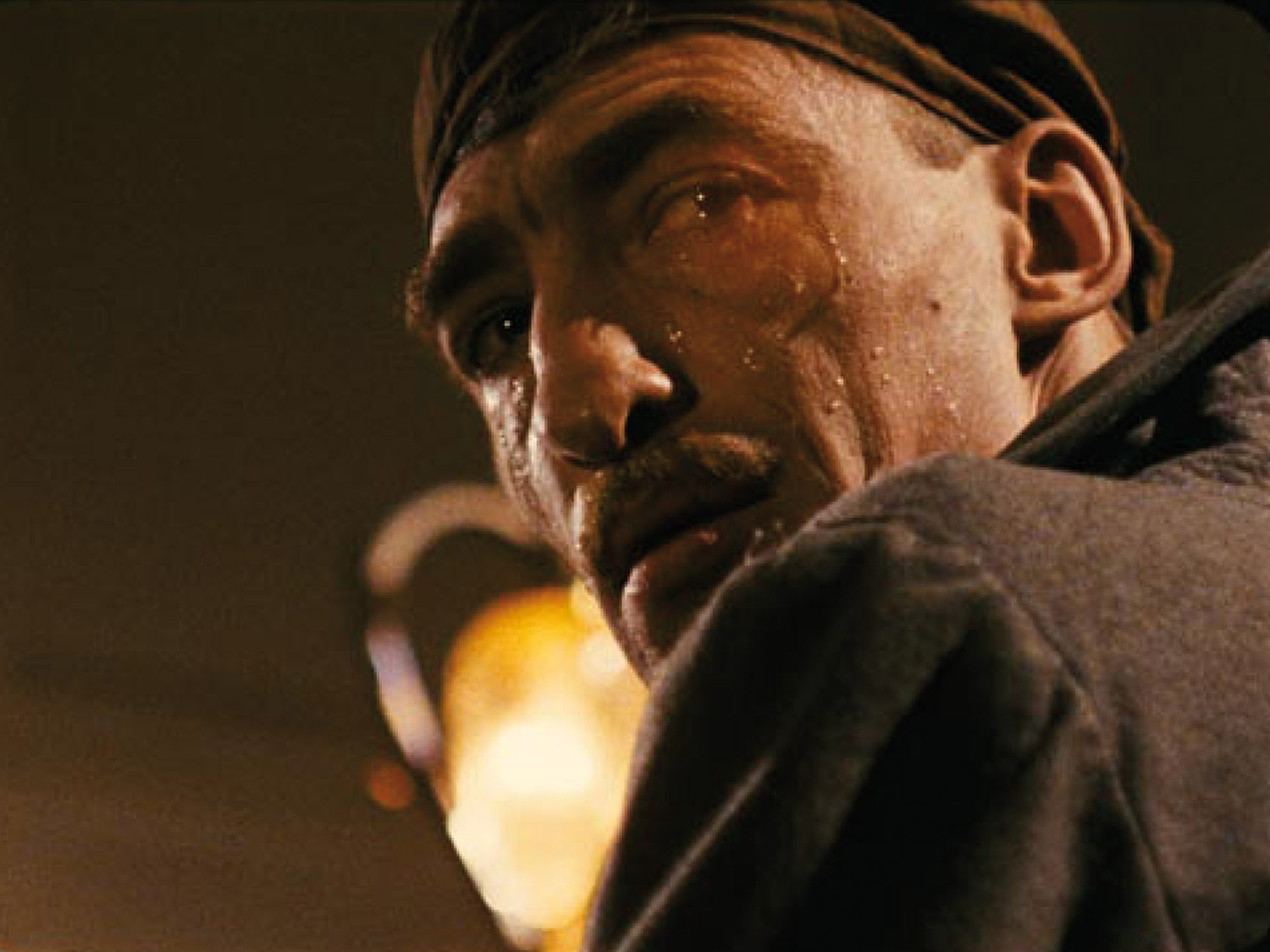

Housing projects are the violent and romantic setting of Desniansky Raion (2007), a fascinating — simultaneously attractive and repulsive — video shot in Paris, St. Petersburg, Belgrade and Kiev. Conceived as a triptych, it successively shows a street fight between two gangs, a sound-and-light show with fireworks celebrating the collapse of a massive tower block, an aerial view of a suburb of Kiev and its geometric housing complexes. The extreme violence and absurdity of the assaults is reinforced by the brutality of the architecture. The music (produced by the artist’s band The Landsc Apes, aka Koudlam) plays an important role by generating a complete loss of spatial and temporal landmarks. It also transcends the different moments to form what Gaillard defines as “a new definition of an urban form of Romanticism.” In his work, the political and social context in which these tower blocks were created is less interesting than the constructions. Indeed, one of his unrealized projects consists of a park of ruins in which tower blocks would be gathered and finally authorized to become ruins.

“Homes & Graves & Gardens,” the exhibition on the Island of Vassivière, in France, connects different sites and histories: the landscapes (the villages were flooded after a dam was built at the end of the ’40s) and the island (the park was severely hit by a storm at the end of the ’90s). On July 14th, the artist organized an indoor fireworks show in a lighthouse, a large wall of sound buried in the forest, a concert by Koudlam conceived as a sonic architecture for the sculpture park and the modification of the Art Center’s façade. The island became an artwork saturated with testimonies of the past and the present. Romanticism and decay are again at the core of this project. By mixing different sources, Gaillard looks for strategies to provide new perspectives. As Smithson said in his essay Entropy and the New Monuments, recalling Vladimir Nabokov’s observation, “The Future is but the obsolete in reverse.”