It’s hard to miss Chen Tianzhuo when you meet him for the first time; whereas most artists in Beijing dress like either Caribbean tobacco barons or contractors on their way to a construction job, Chen has a dress code — perhaps bordering on a compulsion — according to which he doesn’t go out without at least five different colors on his body, and usually many more. He is a personality, immediately recognizable to a growing crowd of fans and friends everywhere, from the underground clubs of Shanghai’s Yongfu Lu to the brand-obsessed streets of Beijing’s Sanlitun. With a presence like this it would be easy to conflate his personality and his process, but this life-performance, as it were, is really only one aspect of the artist’s project. He relies on integration into networks based on fashion, design, celebrity and subculture to gather material for and circulate his work, but the resulting images and objects belong unmistakably to contemporary art — he just speaks a different visual language from the pleasure-denying intellectual masturbation we have grown used to today.

Chen was born in Beijing in 1985 and continues to live in Maizidian, a corner of the city dominated by socialist-era housing blocks roughly halfway between the downtown core and the northeastern art districts. The neighborhood has a distinctly Japanese-German vibe, and somehow this odd cosmopolitanism suits him well (see, for instance, his short-lived luxury brand Tianzo Maizidian, which only managed to release a single collection for the spring and summer of 2012; one suspects the prosthetic arms and gut-strewn breastplate he offered hadn’t yet found their target market). Chen studied graphic design at Central Saint Martins, in London, before switching to fine art at Chelsea College of Arts; his time in London gives him easier access to what’s happening in Western art and visual culture, which makes him one of the best communicators and connectors on the Beijing scene.

His work is unique in China in part because he turns down many of the opportunities that come with belonging to a regional art system. Whereas most young artists would move to Beijing to attend the Central Academy of Fine Art and then automatically transition into working as an assistant for a more established artist, Chen returned to Beijing and spent time working on exhibitions for The Outlook, one of the country’s leading design magazines. Whereas most artists would position themselves for shows or representation at one of the core 798 Art Zone galleries, Chen chose Shanghai’s smaller Vanguard Gallery and Beijing’s suburban Star Space for his first two solo exhibitions. All of which suggests he understands art-world dynamics but isn’t particularly interested in letting them affect his work or his personal life.

The central concerns of Chen Tianzhuo’s work, at least for the moment, lie in the development and codification of a fictional (initially, at any rate) cult that worships the deity Adaha; its tenets are as unexpectedly universalizing (anti-racism, anti-gender distinction, anti-sexual discrimination) as its aesthetics and representations are shockingly juvenile (South Park’s Cartman, for instance, as an important icon of equal-opportunity racism). A recent performance, ADAHA (2014), personified the goddess with two of Chen’s favorite performers, Beio and Qian Lirong. Involving projection and butoh-inspired gyrating on behalf of the two biologically male dancers, the event escalated quickly with both tearing chunks of raw mutton from the floor with their teeth, ultimately leading toward one dancer inserting a butt plug capped with a long, purple horse tail and the other tucking his genitals away. This performance is augmented by a trilogy of videos, each of which delivers new characters into the mix. PICNIC (2014), the earliest of the three videos, breaks with Chen Tianzhuo’s overarching projects by simplifying some of his more complex and anthropologically derived religious iconography into symbols that are a bit more cartoonish. The butoh dancer in blonde pigtails is there, joined by two short actors wearing bone jewelry from some of Chen’s earlier sculpture. There is an astronaut, a recurring figure, who methodically packs and lights a bong. Behind him, two flags bear the icons of the Adaha movement, including a trinity of phalluses and the phrase “Jerk Off in Peace.” The video’s frat-boy elements are balanced by the suggestion of a radical queering, a lifestyle that, at least in mainland China, is still far from mainstream.

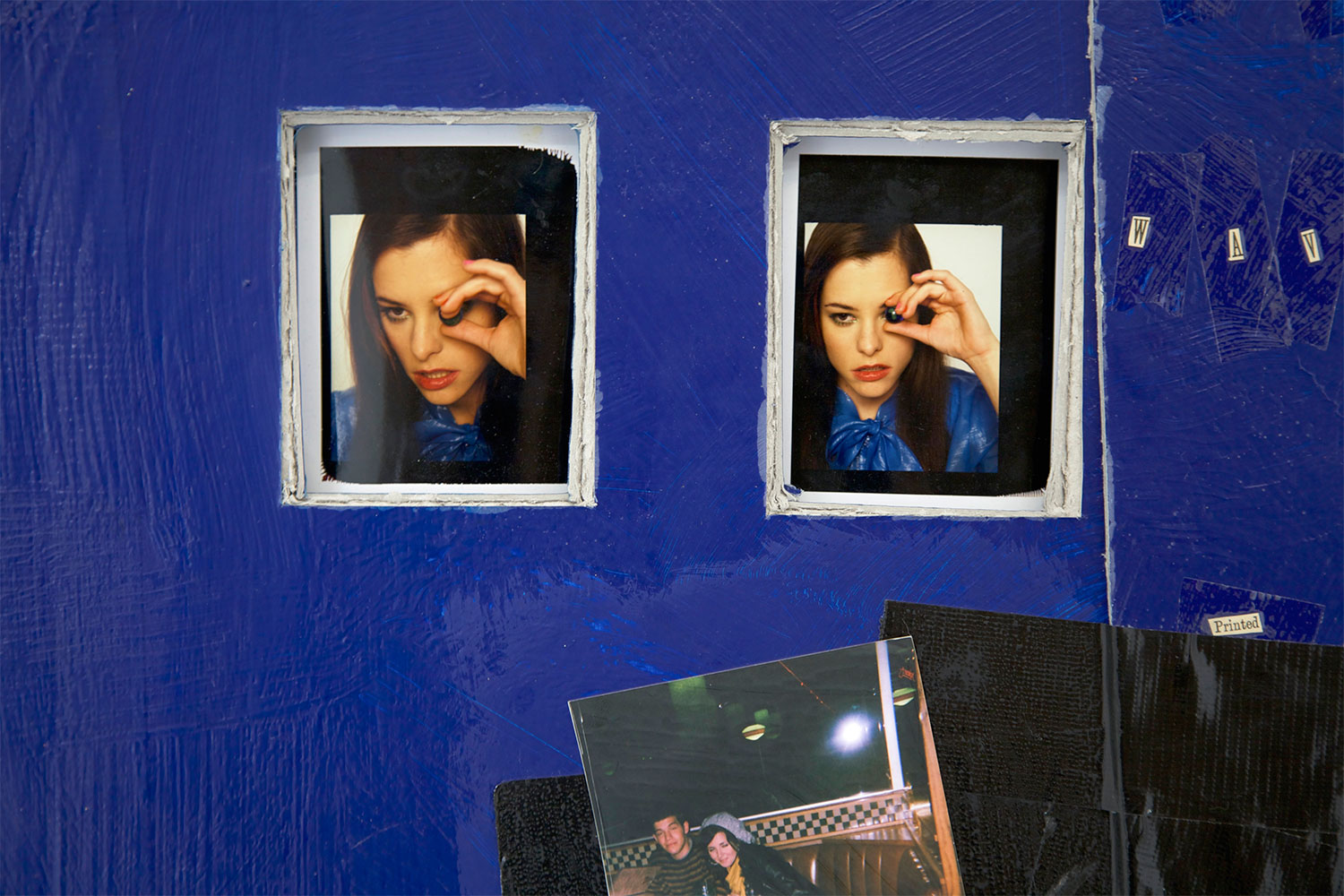

Next up is PARADI$E BITCH (2014), which brings back the Alien Twins from PICNIC and this time covers them in tattoos — the same tattoos on the artist’s own torso. Replacing the indie rock of the first video with Cantonese hip-hop, this piece is more music video than narrative video art. It collects many of the artist’s pervasive symbols: long purple wigs, ray pattern backgrounds, floating eyeballs, Cartman, “Jerk Off in Peace,” gold jewelry and grills. 19:53 (2014), commissioned in partnership with an entertainment conglomerate, steps further out of this comfort zone, but manages to retain Chen’s fascination with fundamentally weird casting despite the inclusion of some more conventional stars. The Dope Girls, cheerleaders or disciplines or acolytes of some kind, surround Adaha on a hexagonal altar; a new character throws a chicken around with his teeth. At this point the resistance to narrative becomes surprising, as if the artist were pushing toward a space defined purely by atmosphere — the profusion of pure images, rather than their sequence.

This is what Chen is focusing on at the moment, and further developments within the Adaha series are already in the pipeline. But, as an artist, his practice is not based on parties and music videos; his work is remarkably grounded in studio fundamentals. See, for instance, the series “Drawing of the Dead” (2011–ongoing), which consists of marker sketches on the incense paper that southern Chinese communities burn to honor deceased relatives. As with his videos, Chen begins with the juvenile, if not puerile: a penis over a Kronenbourg 1664 beer label, the phrase “BITCH SUCK MY DICK” emerging from fallopian tubes reimagined as snakes. But the tone quickly lulls the viewer into something like a television coma, and deft painterly gestures appear in the oddest places, as with “PRAY FOR YOU” appearing over the infamous high-speed rail collision near Wenzhou in 2011, or a group of people in skeleton costumes around a bonfire and a levitating cannabis leaf. Chen’s sculptural practice is similarly sensitive to space and the circulation of his icons. Kangrinboqe (2013) covers Tibetan Buddhist figures with blacklight paint; more minimally, other sculptures dangle bones over other objects, like shark jaws over Chinese medicine dummies, or a bony fish beak thrust directly into a wall.

Fashion is the final component that rounds out Chen’s oeuvre. In some ways it is the combination of everything else: scenography, soft sculpture, image-making and brand dynamics. In another sense, it is a base — a culture from which to appropriate images that remain untouched by the more critical concerns of the contemporary art world, within which Chen Tianzhuo hopes to see his work circulate. It is for this reason that he recently abandoned his celebrated collaboration with the rising designer Sankuanz after several seasons: the logic of the fashion system proved overpowering, encouraging reinvention for the sake of the new and repetition for the sake of the brand. While it lasted, however, Chen’s interventions were brilliant. For Shanghai in fall and winter 2013 he cast models, including several fellow artists, as Tibetan monks, collaborating on backpacks seemingly ripped from monastic friezes and long robes peppered with his trademark cartoon images. In London for spring and summer 2015, he outfitted his models with massively oversized gloves and oral lighting devices, covering them in his print designs from head to toe.

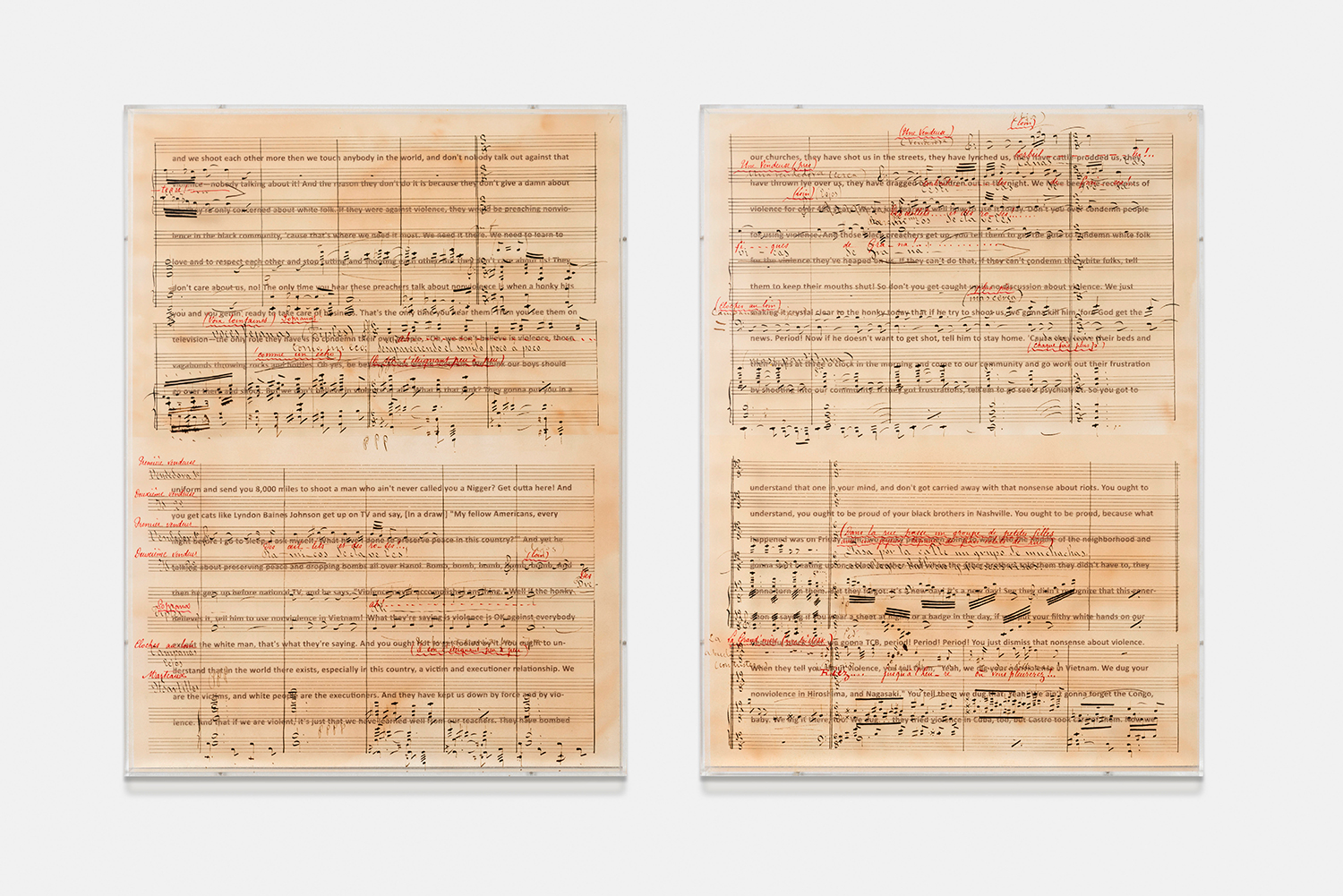

Chen Tianzhuo is currently working on a project that will bring all of this together: an opera dedicated to Adaha, which will combine his objects, video projections, musical soundtracks, costumes and everything else. It is intended to be a live event, raising the question: What comes after the realization of such a Gesammtkunstwerk? The flaw in Chen’s manner of working is precisely in its lack of direction, in the feeling that all of his objects and moving images add up to a practice that, in total, is far more than the sum of its parts. How might this disembodied composite evolve? Performance is playing a growing role in this effort, and one suspects that coming productions may be reinvested with the theatricality of the fashion show. Chen has spent several years proving that his work is not reducible to his persona; the task ahead is to prove that his contribution as an artist is not reducible to his collaborations.

He does have experience with the “total work of art” (that long-expired phrase that still carries so much meaning in today’s China): for his first Beijing solo exhibition, Chen orchestrated “Tianzhuo’s Acid Club,” a one-night pop-up party in a distant studio cluster that brought out all of the city’s club kids. Together with the installations that decorated the space (shelves of bongs, flags and other props from his videos, neon signs, blacklight paint on religious objects, and of course a statue of Cartman), the detritus from the evening (beer bottles and cigarette butts) became the stuff of the exhibition. This production, which could indeed be called theatrical, taught Chen to visualize individual fragments of his practice in motion, activated by actors and viewers alike. It is the resulting ecological dynamic that seems likely to dominate his practice going forward; what we see is neither the relational aesthetics of a certain class of more sentimental artists nor the art-as-party mantra ultimately coopted by Jeffrey Deitch, but rather an attempt to take one Chinese subculture — the club — and merge it into another: art.

Chen’s use of the subculture is what makes his work travel so well. It is easily legible and relatively universal for anyone vaguely familiar with its parameters. Still, while underground party culture may be relatively new to China, the same cannot be said for the global art world. In something of a bait-and-switch tactic, Chen Tianzhuo offers a universe with which we are familiar, and then draws new connections between its constituent parts. In the Beijing context, what is fresh and new is the fact that an artist would be willing to draw from the imagery of popular culture and the underground; as soon as it makes it out, the nucleus of the work shifts, and it is the specific connections between spirituality, clubbing, cartoons and drugs that become interesting. Chen’s world relies on a veil of the strange, no matter the background of the viewer, but, when it is punctured, we realize just how familiar everything really seems. Until, of course, we think back to the artist in Maizidian, leaving his 1950s socialist apartment for sausage and sake, where he is joined by stoned astronauts and erotic dancers who moonlight as magazine editors.